Learn How to Solo With Chords Jazz Style

Master the beautifully musical style of soloing with chords, just like the jazz greats.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The conventional roles of the lead and rhythm guitarist are quite clear: The rhythm guitarist plays chords that accompany the lead guitarist, who plays the usually higher, faster and “more important” single-note material. This dichotomy, however, is not always true or musically desirable, and the guitar’s long history includes many players who have chosen to explore the middle ground – “soloing” using a variety of chords for both harmonic support and textural variation.

It may at first seem overwhelming to consider soloing with chords when it’s hard enough to learn chords and scales separately, especially considering the guitar’s asymmetrical tuning (with the G and B strings being tuned a major 3rd apart while all the other pairs of adjacent strings are tuned in perfect 4ths). And it must be noted that a guitarist who can solo effectively with chords in a variety of contexts knows both music theory and the guitar fretboard very well indeed, as one needs to be agile both creatively and technically to utilize this approach.

Fortunately, one can develop knowledge and skill in this area through a series of conceptual and practical exercises. Although there are many highly accomplished blues, rock, soul and pop chord soloists, we’ve opted to focus on the genre of jazz here, because it allows us to experiment with a wide range of melodic, harmonic and modal concepts, from the minor pentatonic and blues scales to standard jazz-style chord progressions to modes.

These concepts can, of course, be applied to other styles you like, but the rich, eclectic and beautiful world of jazz guitar is a great place to start with this study. Working on these ideas will improve your soloing, allowing greater harmonic support and independence, particularly when playing in smaller ensembles, such as a guitar-bass-drums trio. They’ll also help you incorporate a greater variation of textures into your lead playing, other than just single notes, which can help you build a solo effectively and keep it interesting, especially when playing with a clean, undistorted tone.

This lesson includes 11 exercises/examples, presented in two parts that focus on and demonstrate various useful chord soloing concepts and approaches. In this first part, we will look at five examples that demonstrate the following:

- How the all-important minor pentatonic and blues scales can serve as a basis for octave, double-stop and chordal soloing.

- Bluesy double-stop ideas for dominant 7 chords all over the fretboard.

- How to build agility and fluency with minor 7, dominant 7 and major 7 chord shapes on the guitar’s top four strings.

For purposes of illustration and comparison, we’ve chosen to use just one key center for each concept, but transposing these ideas to and practicing them in different keys and contexts is essential to properly absorb them, so be sure to do that on your own.

So dial in an appropriately clean and warm-sounding neck-pickup electric guitar tone, and let’s get started!

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

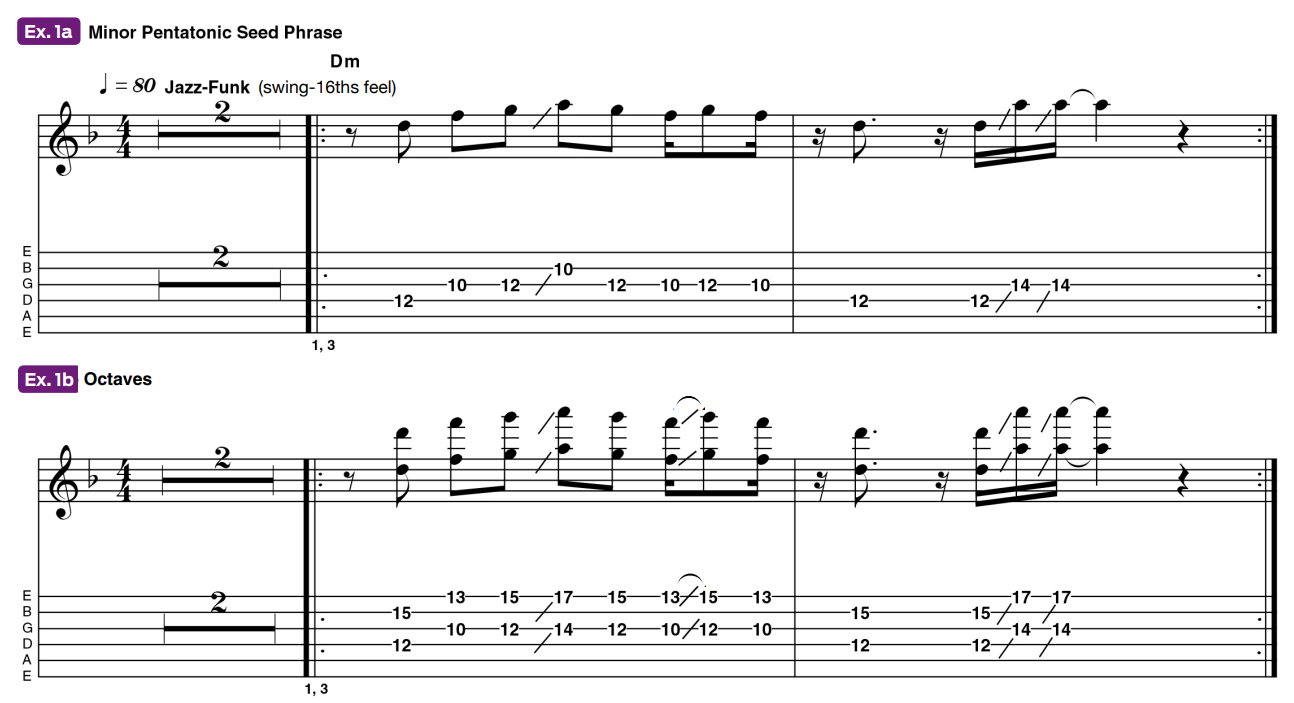

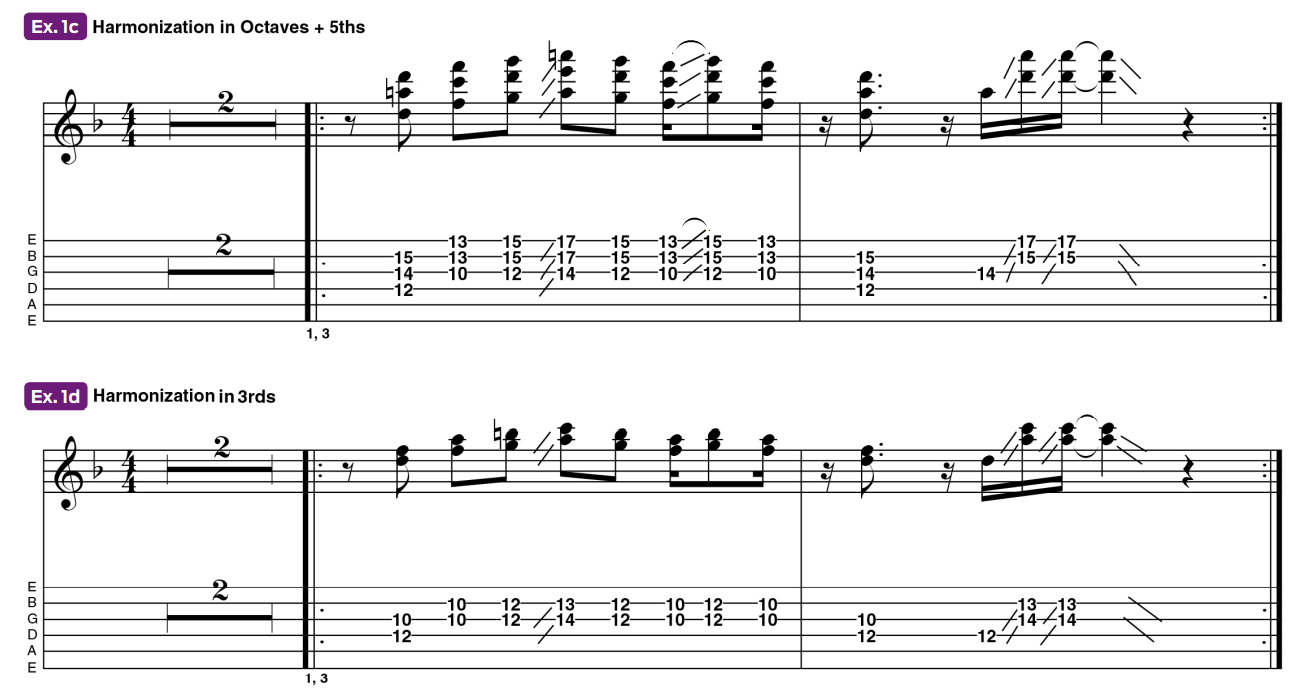

We’ll begin by looking at an example of how to construct a chord solo from the minor pentatonic scale, specifically D minor pentatonic (D, F, G, A, C). Ex. 1a presents a simple “seed phrase” that we will use to build a number of chord solo ideas. Ex. 1b shows the same melody played in strummed octaves using an approach popularized back in the 1960s by the legendary Wes Montgomery, with each melody note doubled an octave higher.

When playing octaves like this and moving up and down the fretboard, it helps to visually focus on the lower note, fretted with the 1st, or index, finger while maintaining a constant three-fret distance between it and the 4th finger, or pinkie, which is two strings higher. Be sure to mute the unused string between each octave pair with the “paw” of your 1st finger, to prevent it from ringing as you strum across all three strings. To emulate Wes’ warm, jazzy touch, strum the strings with downstrokes of your pick-hand’s bare thumb. Note that, when playing strummed octaves on the A and G strings or the low E and D strings, the octave-higher note would only be two frets higher, not three, due to the way the guitar is tuned.

Building upon this strummed octaves idea, Ex. 1c adds a note that’s either a perfect 5th or 4th above each low melody note, producing a subtle and harmonically rich variation that has a “throaty” and sort of “power-chord-like” quality that brings to mind the sound of an electric organ and its prominent overtones. George Benson and Grant Green have made great use of this root-5th or root-5th-octave harmonization technique in many of their guitar solos. Be sure to barre the notes played at the same frets on the top two strings with your pinkie.

Inspired by Kenny Burrell, Ex. 1d takes our foundational minor pentatonic melody and instead harmonizes it in major and minor 3rds. This adds an additional “color tone” to the minor pentatonic scale – the major 6th, B, which is played above the G note – implying the interesting sound of the D Dorian mode (D, E, F, G, A, B, C). This approach can be highly useful in many minor-key contexts.

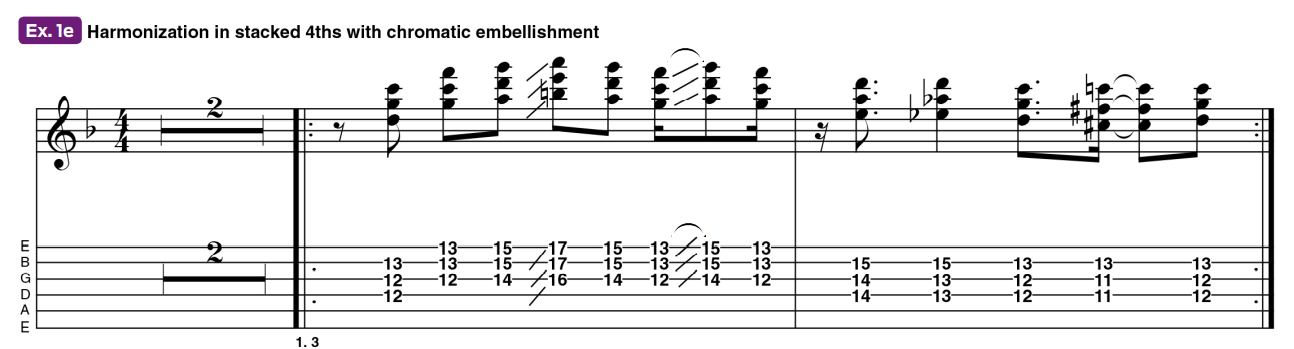

Finally, like the three-note, root-5th-octave “stacks” we looked at in Ex. 1c, Ex. 1e takes a similar approach with three-note chords, one that’s more edgy and modern sounding, inspired by the styles of players like Robben Ford and Joe Dioro.

Here, each note of our foundational melody, which has been slightly altered, has two 4ths stacked above it (a 4th and a 4th above that note), producing what’s known as quartal harmony. For added dissonance, the lower two notes can be altered chromatically, as demonstrated in bar 2. Actually, in this case, the focus shifts to the top note, which can serve as your guiding melody note.

When utilizing this approach, you can think of the highest note as being harmonized below with a pair of 4ths that form a “sub-stack.”

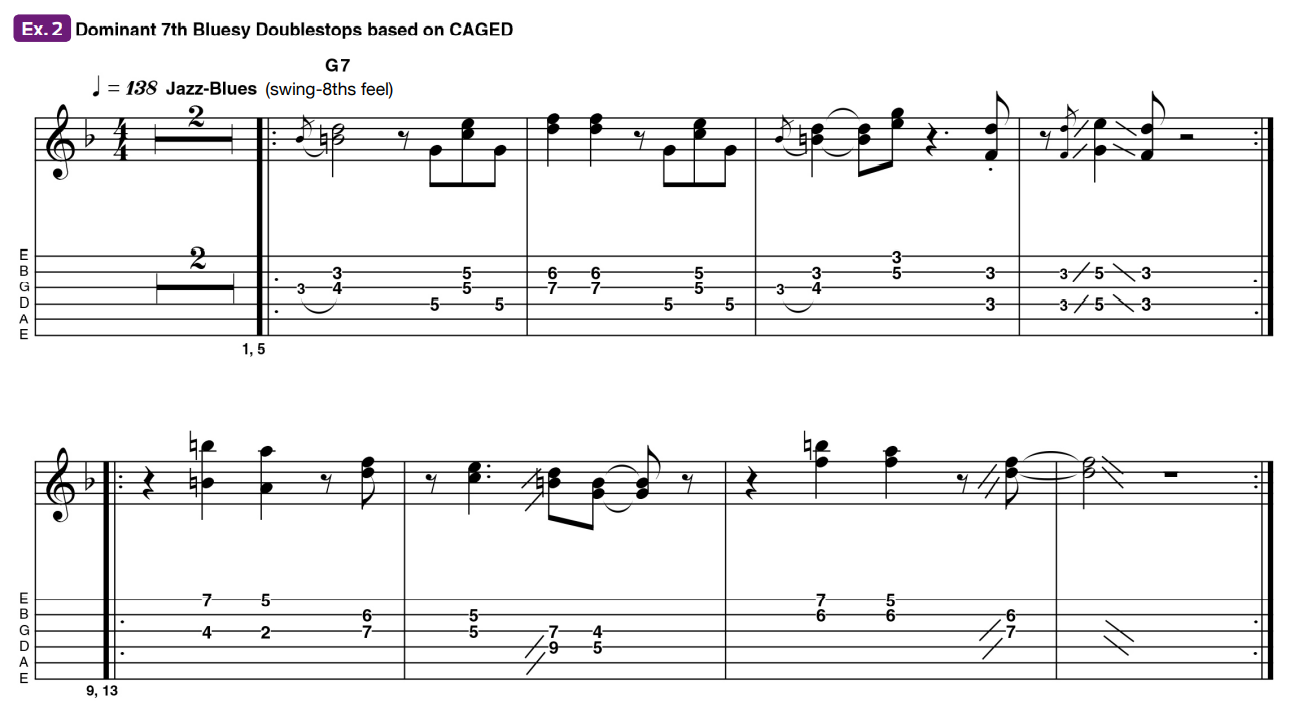

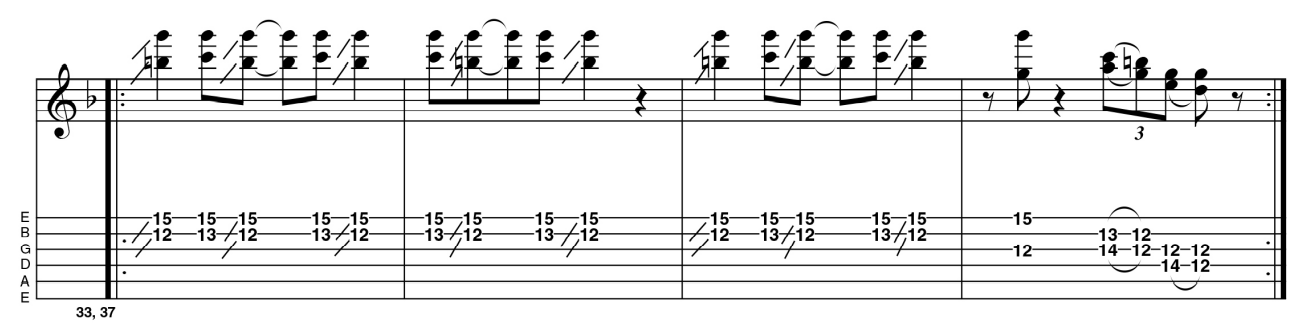

Ex. 2 presents a variety of jazz-blues-style double-stop ideas, which are great for playing over many dominant 7 chords. These are all in the style of George Benson, and I’ve given an idea for each of the five CAGED shapes, so that you will always have one to work from.

Experiment with transposing these licks and phrases to other keys and using them over a blues progression, as well as over static dominant-7 chord vamps. We also recommend writing your own double-stop riffs for each position.

In order to solo with chords effectively, one needs to know several chord types everywhere on the fretboard, so let’s be thorough and dig deep into some fundamental chord qualities: minor 7, dominant 7 and major 7. The better we know these chord types and their various shapes, the more fluently we can navigate a range of progressions, and even harmonize any melody with any chord, which is a great goal.

For further study, be sure to check out the ballad-playing styles of Joe Pass, Charlie Byrd and Wes Montgomery for inspiring examples of this sort of approach.

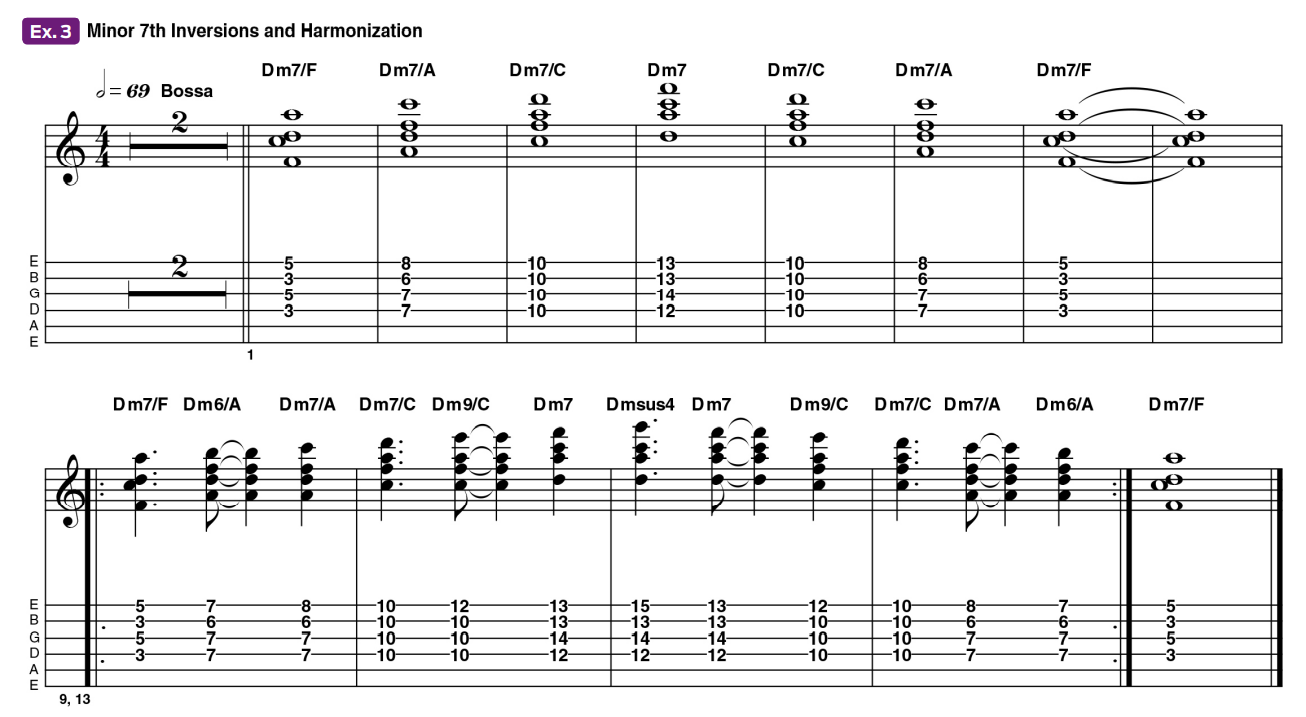

In our last examples this lesson, we’ll look at minor 7, dominant 7 and major 7 harmonization. Ex. 3 shows every available inversion of a Dm7 chord played on the top four strings, followed by how they can be used and altered slightly to harmonize an ascending and descending D Dorian melody on the 1st string. (The D Dorian mode “agrees with” a Dm7 chord beautifully.)

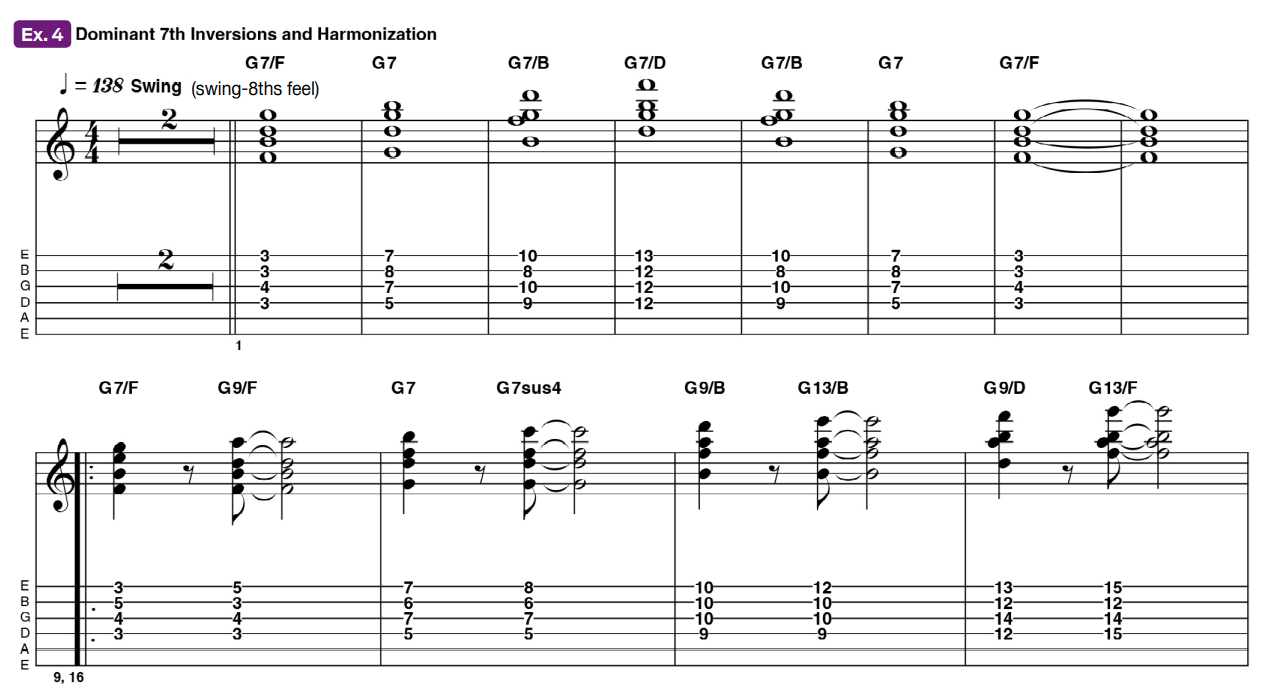

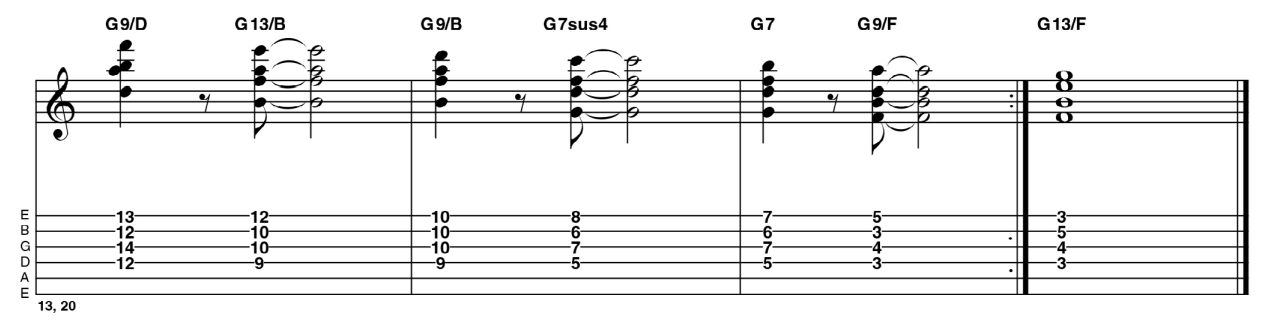

Ex. 4 similarly shows the inversions for a G7 chord on the top four strings, followed again by the harmonization of an ascending and descending scale, this time the G Mixolydian mode (G, A, B, C, D, E, F) with a simple rhythm. Note that G Mixolydian and D Dorian are built from the very same seven notes, as they are both relative modes of what would be considered the “parent” C major scale, or C Ionian mode (C, D, E, F, G, A, B). Again, practice transposing this information to other keys, as well.

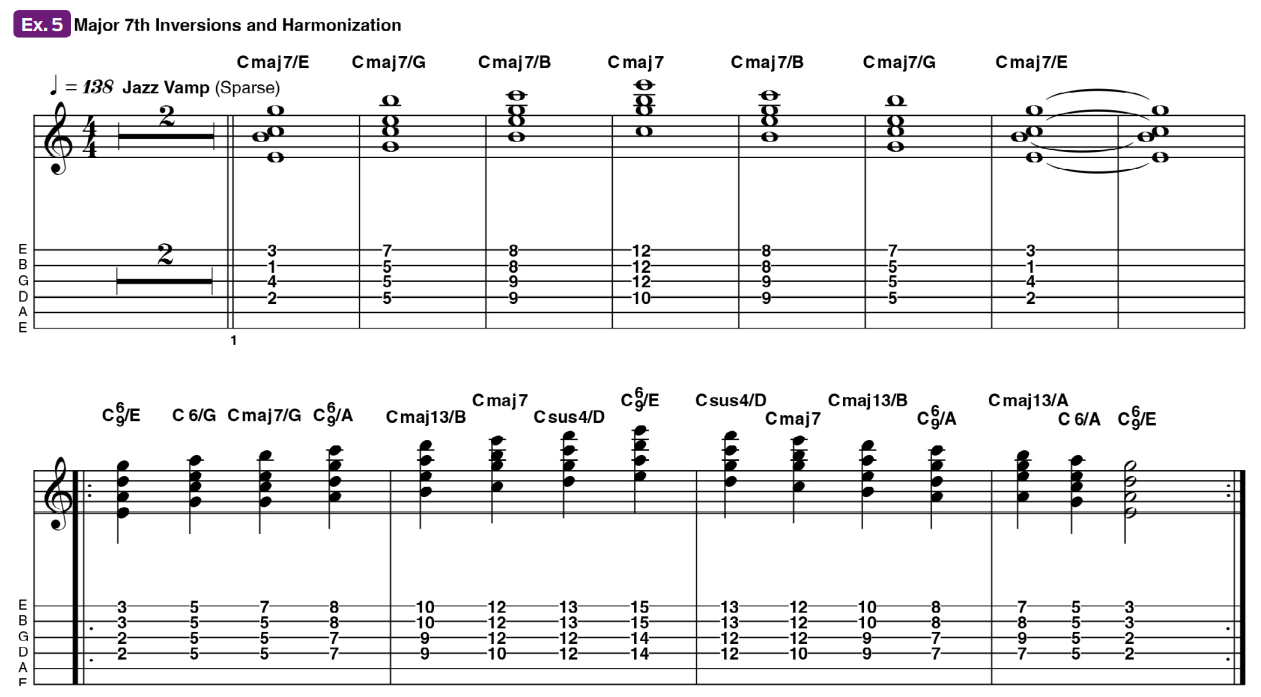

Finally, Ex. 5 presents the available inversions for a Cmaj7 chord on this same string group. For the harmonizations, we’ve used some alternative voicings employing maj6, 6/9 and maj13 chords, partly because the first chord, the utterly beautiful Cmaj7/E, is quite tricky to grab on the fly. You’ll find these solutions to be more agile.

In addition, Cmaj7/B (with the C in the melody and B in the bass) is quite a spiky chord, so we’ve offered the softer C6/9 with the A in the bass as an alternative. Note that all of these chords “live within” the C major scale and provide a general “happy” major diatonicism. You might find that using small two- and three-string partial barres with your fretting hand is easier than trying to finger every string with a different fingertip.

Experiment with what works for you, especially given the speed of some chord changes.

We’ll be back next time to explore working in fundamental modes and their harmonic contexts, and we’ll look at some useful and harmonically appropriate solutions for navigating the jazz style’s essential major and minor ii – V progressions all over the fretboard.

See you then!