“When we broke up, I went into that dark place. I didn’t give a s**t about the music anymore.” The breakup that nearly made Eric Clapton quit music

Slowhand didn’t like the sound of his guitar or how he played. Even the prospect of linking up with a Beatle couldn’t pull him out of his hole

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

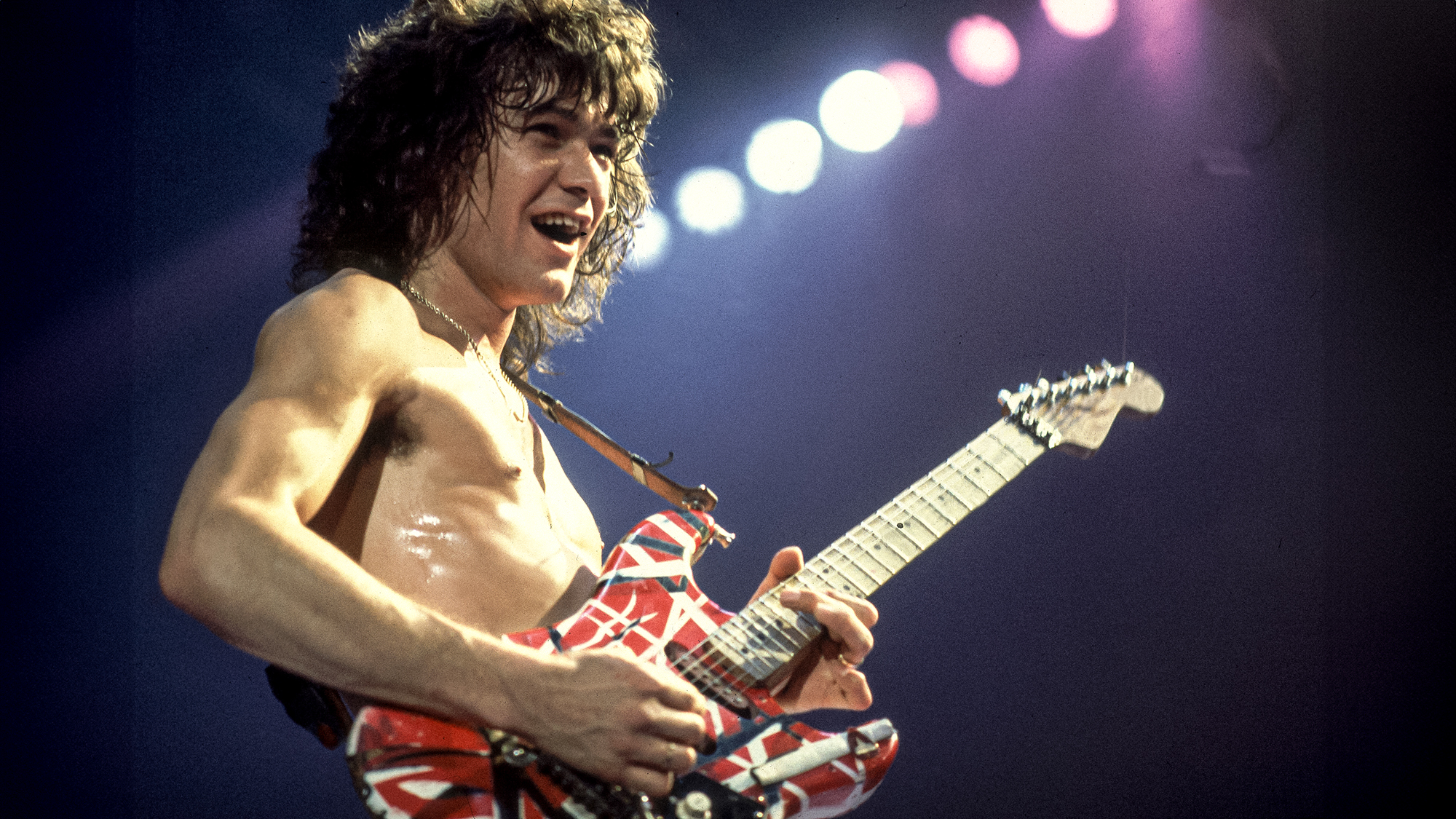

During his early career, Eric Clapton launched a trio of musical acts as he built a fierce reputation as one of the finest guitar players to break out of the British blues explosion. But his dream of having his own group nearly cost him his career.

Clapton’s legend was formed during his brief tenure in the quartet John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, leading someone to spray paint “Clapton is God” on a London wall.

But soon after recording Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton in 1966, he found himself standing mouth agape as he watched Buddy Guy perform in London with a bassist and drummer.

“What it said to me was, 'This was possible,’” Clapton explained. “If you were a good enough guitar player, you could do it as a trio. It seemed to be so free, you could go anywhere.”

He promptly quit Mayall and secretly formed his own power-trio, Cream, with bass guitarist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker. Their group was nearly revealed too soon when the three were picked at random to contribute to a compilation album featuring London's hottest players. When they did come out, Cream became rock's most groundbreaking power trio, much as Clapton had hoped.

But behind the scenes, he anguished over the band's interpersonal tensions as well as Bruce and Baker's jazz leanings.

“Eric thought he was going to have this little blues trio and be like Buddy Guy," Bruce later said of his and Baker's jazz-rooted tendencies. “We had different ideas."

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The band was ultimately run into the ground by their greedy management, who only ever saw the band as a quick cash grab. They even approached Rory Gallagher to step into Clapton's vacated position when the trio inevitably disintegrated in 1968 after just two years .

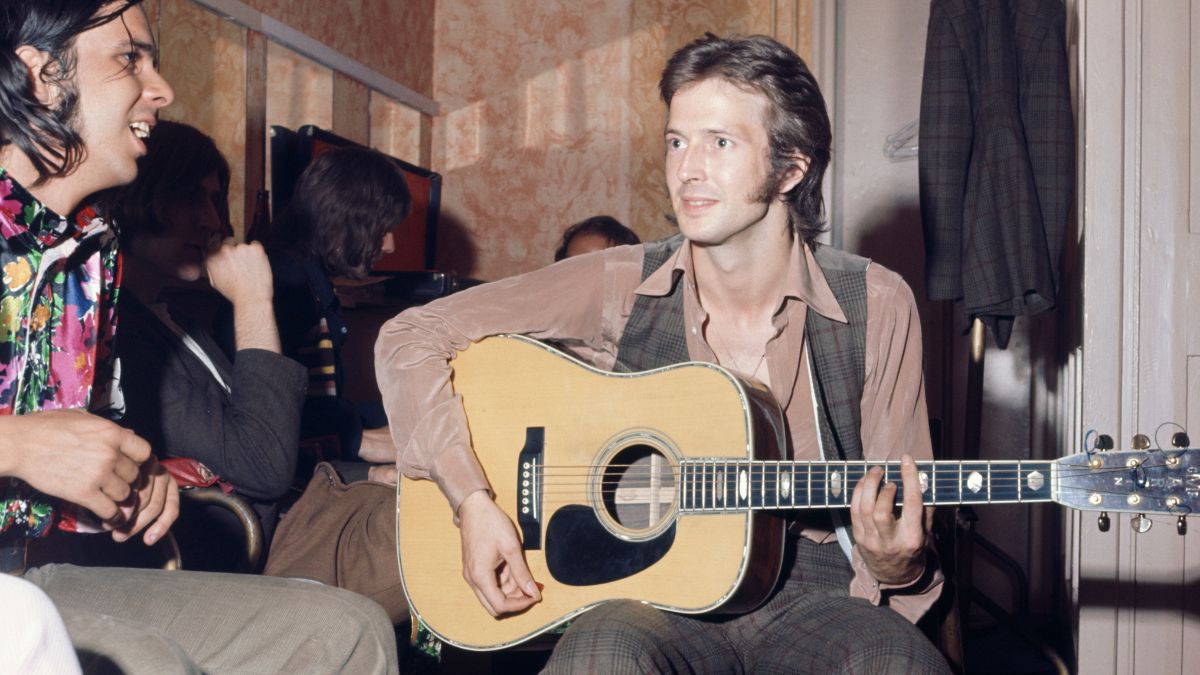

Blind Faith became Clapton's next project. Featuring Traffic keyboardist and singer Steve Winwood, bassist Ric Grech and Baker on drums, the quartet never jelled. After the group was supported on a gig by the American group Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, Clapton saw their brand of southern-fried blues as more to his liking. He befriended frontman Delaney Bramlett, and with his pal Beatle George Harrison in tow, joined the group for a handful of gigs before launching his 1970 self-titled solo album, recorded with the support of the band.

That inevitably led to the creation of his next group, Derek and the Dominos, a quartet designed to give Clapton a degree of anonymity. Formed with members of Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, the project was very close to Clapton's heart. As he revealed shortly before the release of their 1970 album, Layla & Other Assorted Love Songs, he expected Derek and the Dominos to outlive its predecessors. In the end, they made it no further than one album.

There were highs and lows to their time together. Clapton's guitar tandem with Duane Allman, who guested on the record, has gone down in rock as one of the greatest the genre has ever seen. But Clapton was pained by the knowledge their guitar fusion was temporary.

“I knew that sooner or later he [Duane] was going to go back to the Allmans,” he admitted to Guitar World. “But I wanted to steal him.”

In the end, Allman died in a motorcycle accident roughly one year after Layla was recorded. Prior to his death, Derek and the Dominos, minus Allman, regrouped in early 1971 to record their followup. The sessions, Clapton said, “broke down halfway through because of the paranoia and tension. And the band just dissolved.”

“When we broke up, I went into that dark place. I didn’t give a shit about the music anymore,” Clapton told Guitar World. “I didn’t like the sound of my guitar, I didn’t like the way I played.”

Clapton’s drug usage, in particular heroin, had reached its zenith during this period. John Lennon, himself a former heroin user, recognized his friend’s struggles, and reached out to help by asking him to form a new band with him. .

A letter Lennon wrote to Slowhand in 1971 proposed they start a new supergroup together. Among his lines of persuasion, he wrote, “I really feel that I can bring out the best in you and bring back the balls in rock ‘n’ roll.”

The guitarist declined the invitation, confining the project to the annals of what could have been. Lennon’s support did little to pierce his darkness at that time.

Eventually, though, Clapton found his way back, not through blues but through the power of reggae, courtesy of Bob Marley. Clapton would go on to have his first number-one hit — and as a solo artist — with his 1974 cover of Marley's "I Shot the Sheriff."

“When I came back, it was with a different point of view, a fresh enthusiasm, and a kind of open-mindedness to learn about new music,” Clapton told Guitar World. “That’s when I heard reggae. I was just like a kid in a sweet shop again.”

A freelance writer with a penchant for music that gets weird, Phil is a regular contributor to Prog, Guitar World, and Total Guitar magazines and is especially keen on shining a light on unknown artists. Outside of the journalism realm, you can find him writing angular riffs in progressive metal band, Prognosis, in which he slings an 8-string Strandberg Boden Original, churning that low string through a variety of tunings. He's also a published author and is currently penning his debut novel which chucks fantasy, mythology and humanity into a great big melting pot.