The Foxx Tone Machine Was the Fuzz of Choice for Peter Frampton, Billy Gibbons, and Adrian Belew

With its fuzzy looks, sound, and feel this was the dirt box to beat in the '70s.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The ’70s was a bountiful time for analog effects pedals. Among the great fuzz boxes of the era, the Foxx Tone Machine stands proudly as one of the most expressive and more extreme. The pedal was the flagship of Foxx’s lineup, which ran for a few years before vanishing in the latter part of the decade.

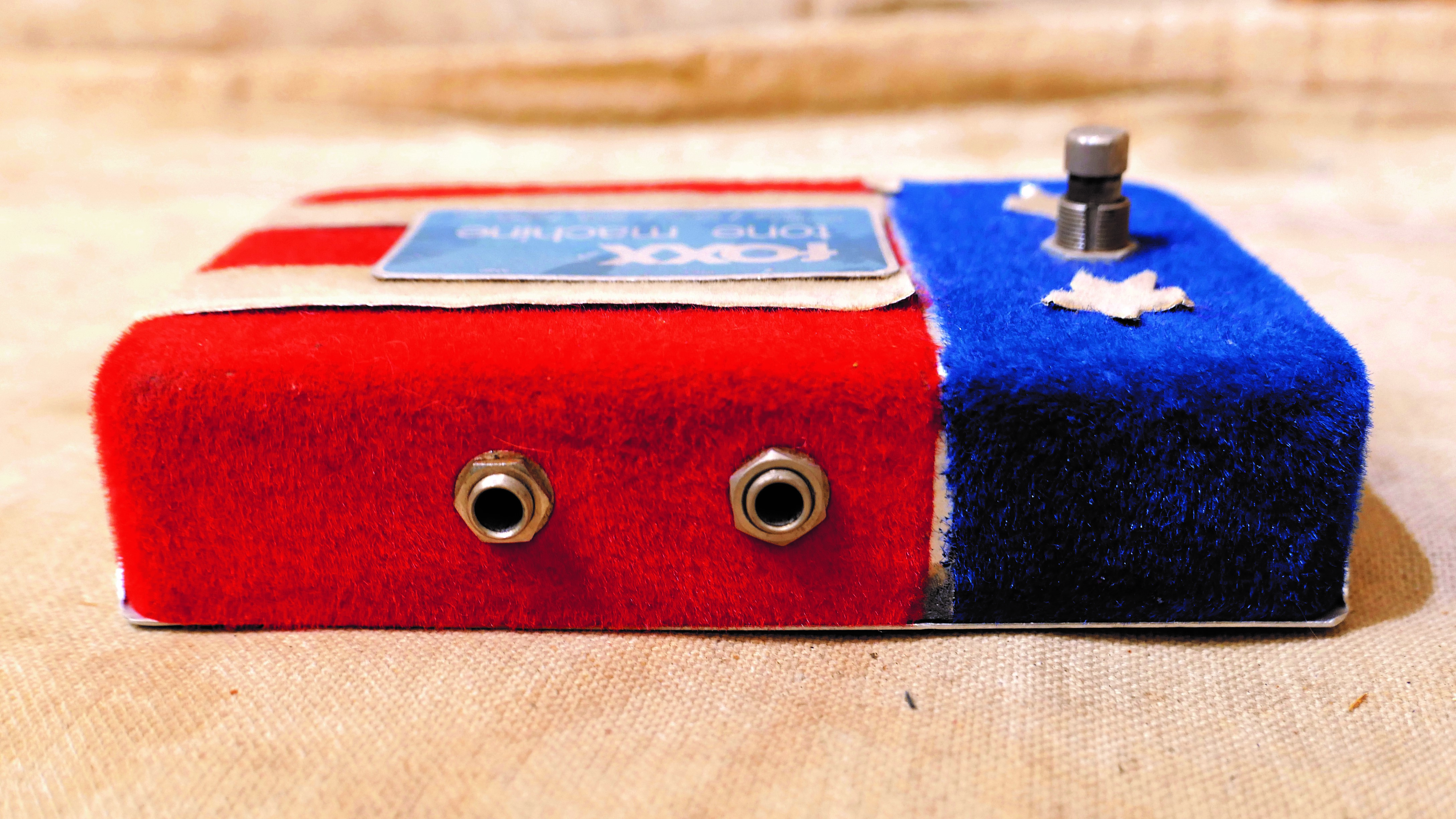

Appropriately for a fuzz pedal, its metal case was covered in tightly cropped red or blue flocking that made it feel as velvety as it sounded. And while the pedals are hard enough to come by, the Stars & Stripes unit from 1972, shown here, is among the rarest.

According to the Tone Machine’s inventor, Steve Ridinger, very few of these red-white-and-blue beauties were made. “My memory is just a few, not 50 pieces,” he says. “It was very laborious masking all the areas to get the different flocking colors.”

Ridinger created the Tone Machine in Los Angeles in 1971, when he was just 19 years old. The circuit within it (which would be used in other Foxx products) was a relatively complex affair that offered more control than the average Fuzz Face or Maestro clone, the likes of which constituted a large proportion of the fuzz boxes available at the time.

The Tone Machine used four transistors and had a very effective octave-up sound (misspelled Octive on the control panel, though corrected in the brochures) that was activated by the toggle switch on the pedal’s side. This was itself a major bonus that performed better than many other octave and octave-fuzz units on the market, underscoring the veracity of the Tone Machine’s name.

The core sound is a thick, textured, gnarly fuzz, but the versatile Mellow-Brite tone control takes it from warm and gooey to bright and razor-like. This knob gives the Tone Machine much more range than most two-knob fuzzes, and even outperforms many others with tone knobs.

While many other lesser-known and also-ran fuzz efforts often failed to hold their own alongside the established classics, the Tone Machine quickly found an enthusiastic following and remained a highly regarded variation on the fuzz theme for decades to come.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Unlike the traditional stompbox-style Tone Machine and its partner, the Phase III, which arrived a little later, the majority of Foxx’s notable products came in rocker pedals that better served their bonus features and put even more control right at the player’s feet.

Among them were the Wa & Volume, Fuzz & Wa & Volume, O.D. Machine, Down Machine (a bass wah-wah), Loud Machine (a passive volume pedal), and Clean Machine, which offered both mellow and fuzzy sustain.

The top dog was arguably the Fuzz & Wa & Volume, often considered the catch of the lineup. In addition to its three obvious functions, it had the useful Foxx octave-up effect and four voicing modes for the wah.

The pedal packed plenty of sonic sculpting power, but it exhibited a few drawbacks. The volume pedal didn’t work quite as it should, while further problems were occasionally caused by the pedal’s inherently original looks. The fuzzy flocking that covered the metal enclosures often worked its way loose and ended up inside the box, where it gummed up the workings of the wah-wah potentiometer and gear.

But of all the Foxx company’s pedals, the Tone Machine remains the one many players loved best, and it grabbed the attention of several star users during its run and after. To hear some of its more extreme sounds, check out much of Adrian Belew’s work, particularly the song “Big Electric Cat” from his 1982 solo album, Lone Rhino.

The pedal’s thick fuzz and octave sounds were also creatively exploited by countless other electric guitar players including the likes of Parliament-Funkadelic’s Michael Hampton, Peter Frampton, Trent Reznor, and Billy Gibbons.

Having created such a legend in just a few years, and at such a young age, Ridinger continued to excel in the industry. In the 1990s, he rose to become head of the Evets Corporation, which purchased the Danelectro trademark in 1995 primarily to use the brand on a range of budget-friendly, retro-minded effects pedals. (Remarkably, Danelectro’s reissue guitars only came along later, after much demand from customers.)

Given Ridinger’s experience in the pedal world, the fact that so many of these colorful and affordable early Danelectro stompboxes also sounded good becomes far less surprising. Among them, the French Toast was based on the original Tone Machine.

Several popular homages to the Foxx Tone Machine have hit the market over the years, including a Foxx-branded reissue in the 2000s. Unsurprisingly, given Ridinger’s history, the more recent Danelectro 3699 Fuzz has received high marks from many players (and an Editors’ Pick Award from GP in 2019).

It includes the bonus of a Mid Boost switch and a second foot switch to kick in the octave effect.

Incidentally, 3699 was the last four digits of the Foxx company’s randomly assigned phone number in the early ’70s (and it spells out “FOXX” on a traditional telephone keypad).

Other options include Warm Audio’s Foxy Tone Box, which goes for the vintage-correct format but in orange flocking, and the Fulltone Ultimate Octave and Stomp Under Foot Silver Foxx, both of which also add a foot-switchable octave.

Wherever you get it, the Foxx Tone Machine is undoubtedly a mighty shape shifter of a circuit.

Essential Ingredients

- Fuzzy flocked covering in red and blue or Stars & Stripes (very rare)

- Controls for volume, sustain (fuzz), and Mellow-Brite (tone), plus Octive (octave) switch

- Original four-transistor fuzz and octave circuit

- Thick, evocative fuzz sound with useful octave-up option

Bag a Danelectro 3699 Fuzz at Sweetwater here.

Thanks to Southside Guitars for showing us these awesome vintage pedals.

Dave Hunter is a writer and consulting editor for Guitar Player magazine. His prolific output as author includes Fender 75 Years, The Guitar Amp Handbook, The British Amp Invasion, Ultimate Star Guitars, Guitar Effects Pedals, The Guitar Pickup Handbook, The Fender Telecaster and several other titles. Hunter is a former editor of The Guitar Magazine (UK), and a contributor to Vintage Guitar, Premier Guitar, The Connoisseur and other publications. A contributing essayist to the United States Library of Congress National Recording Preservation Board’s Permanent Archive, he lives in Kittery, ME, with his wife and their two children and fronts the bands A Different Engine and The Stereo Field.