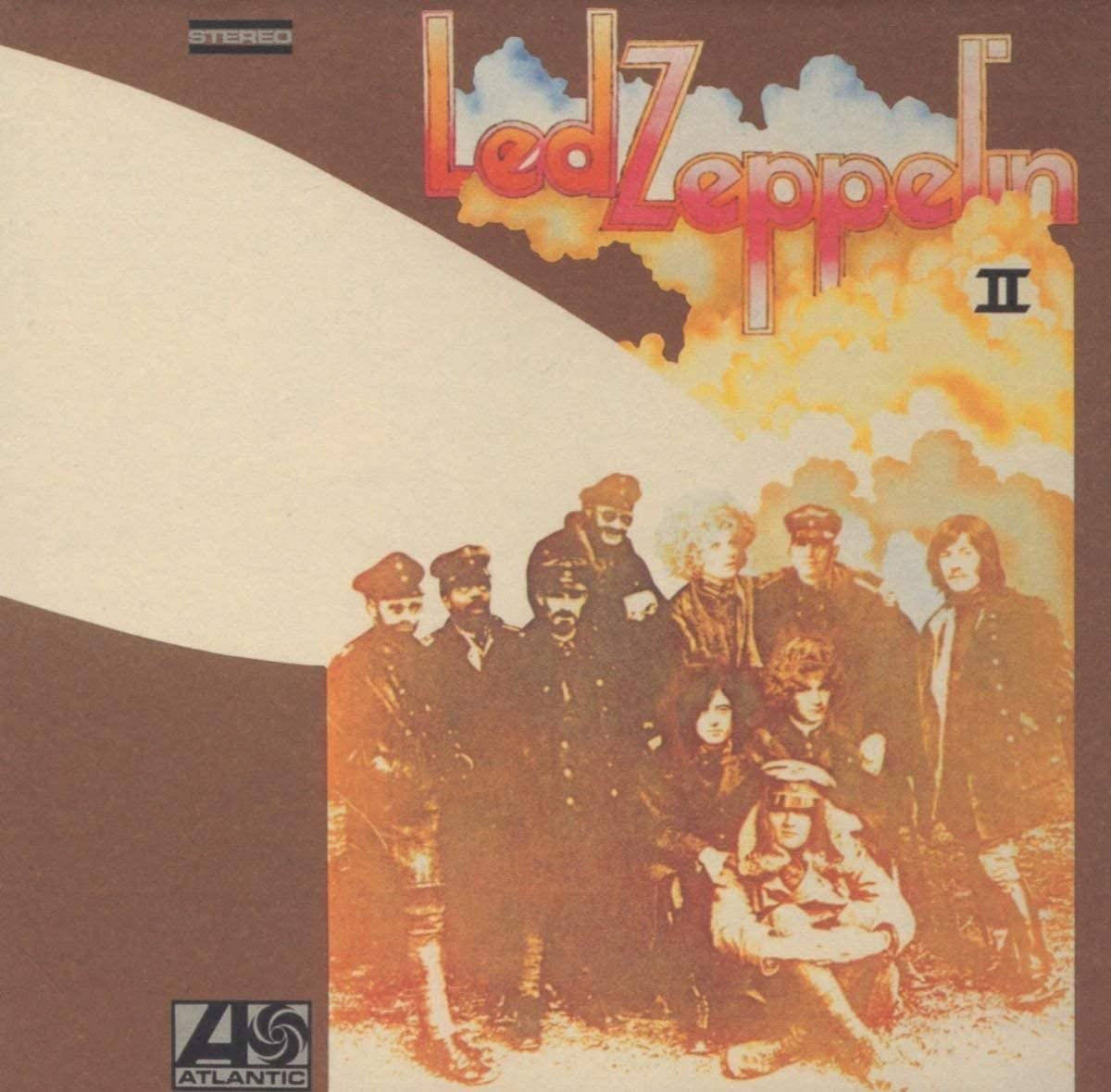

The Definitive Story of 'Led Zeppelin II' Track by Track

Recorded piecemeal in studios across the U.S. and U.K., Led Zeppelin’s second album defined blues-rock at the dawn of the 1970s.

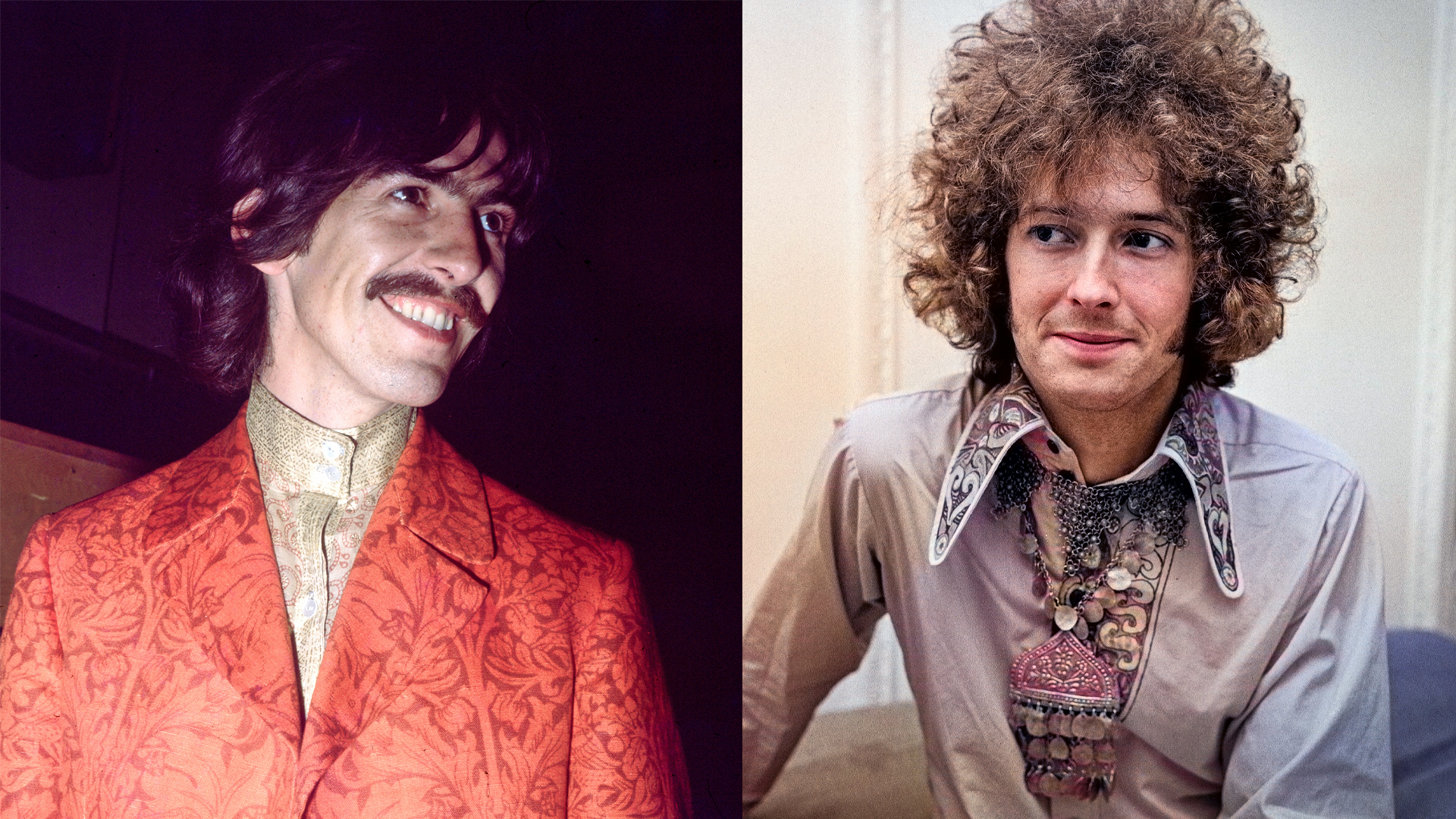

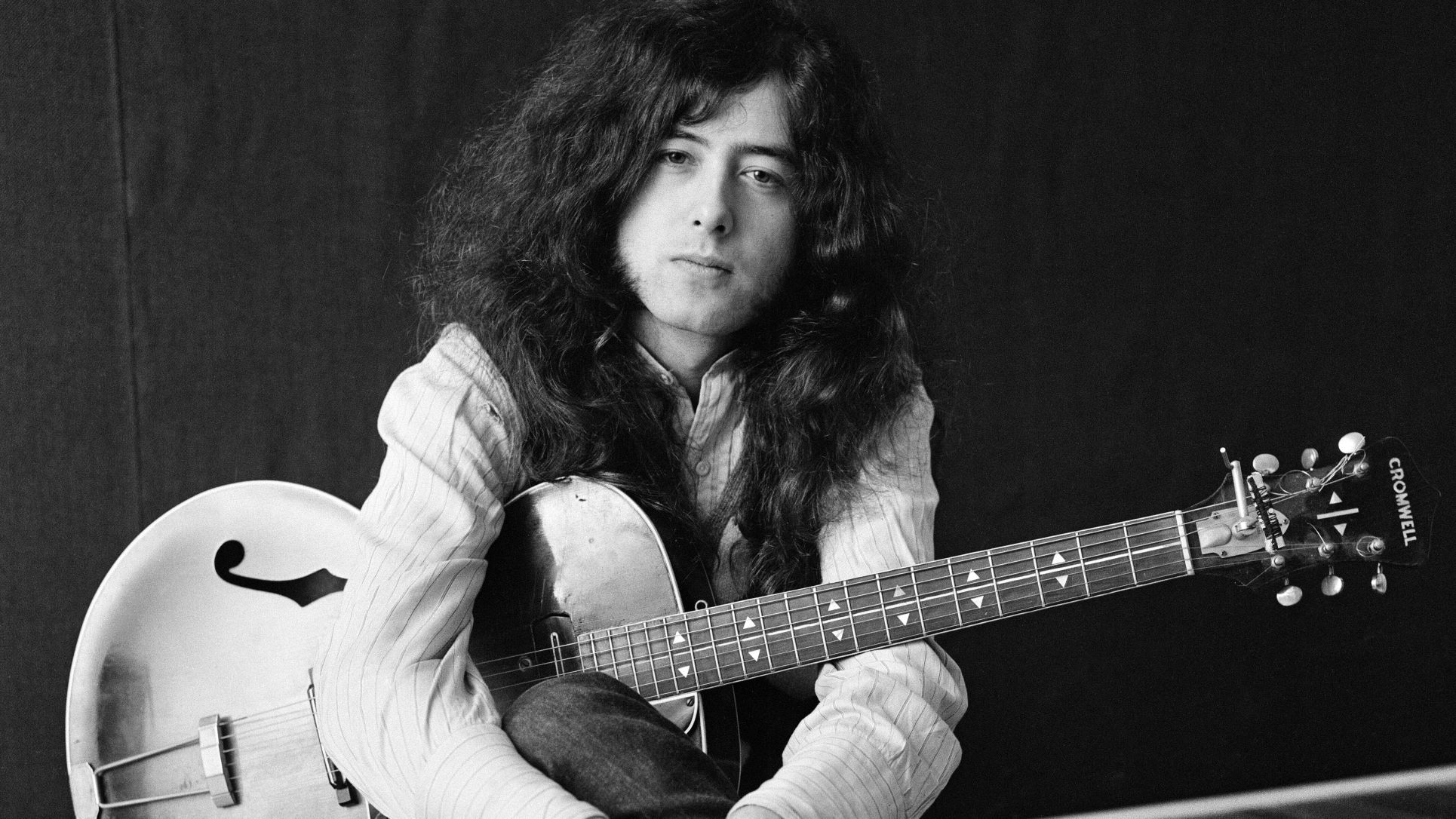

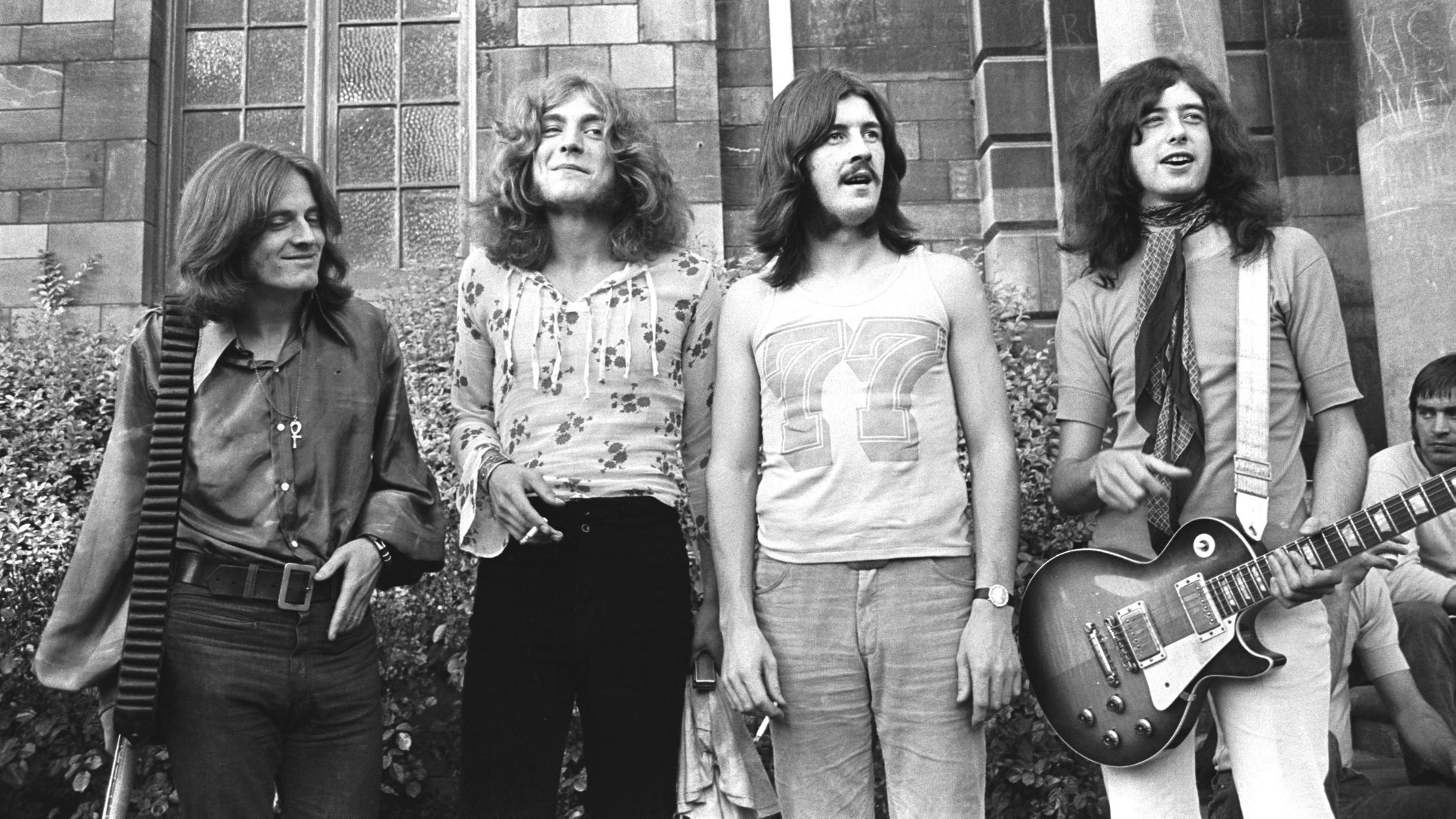

In early 1969, Led Zeppelin upped the ante on Britain’s electric blues boom with their self-titled debut album. Though some heard the record as the first coming of heavy metal, it was in fact nothing less than an epic and thunderous celebration of blues-rock. And it put Jimmy Page and his new band on the map in the U.S.

But before the year was out, Led Zeppelin would out-do themselves with their sophomore effort. Born of real adventures they experienced while touring in America, zig-zagging from coast to coast, Led Zeppelin II was written and recorded piecemeal in studios across the U.K. and U.S.

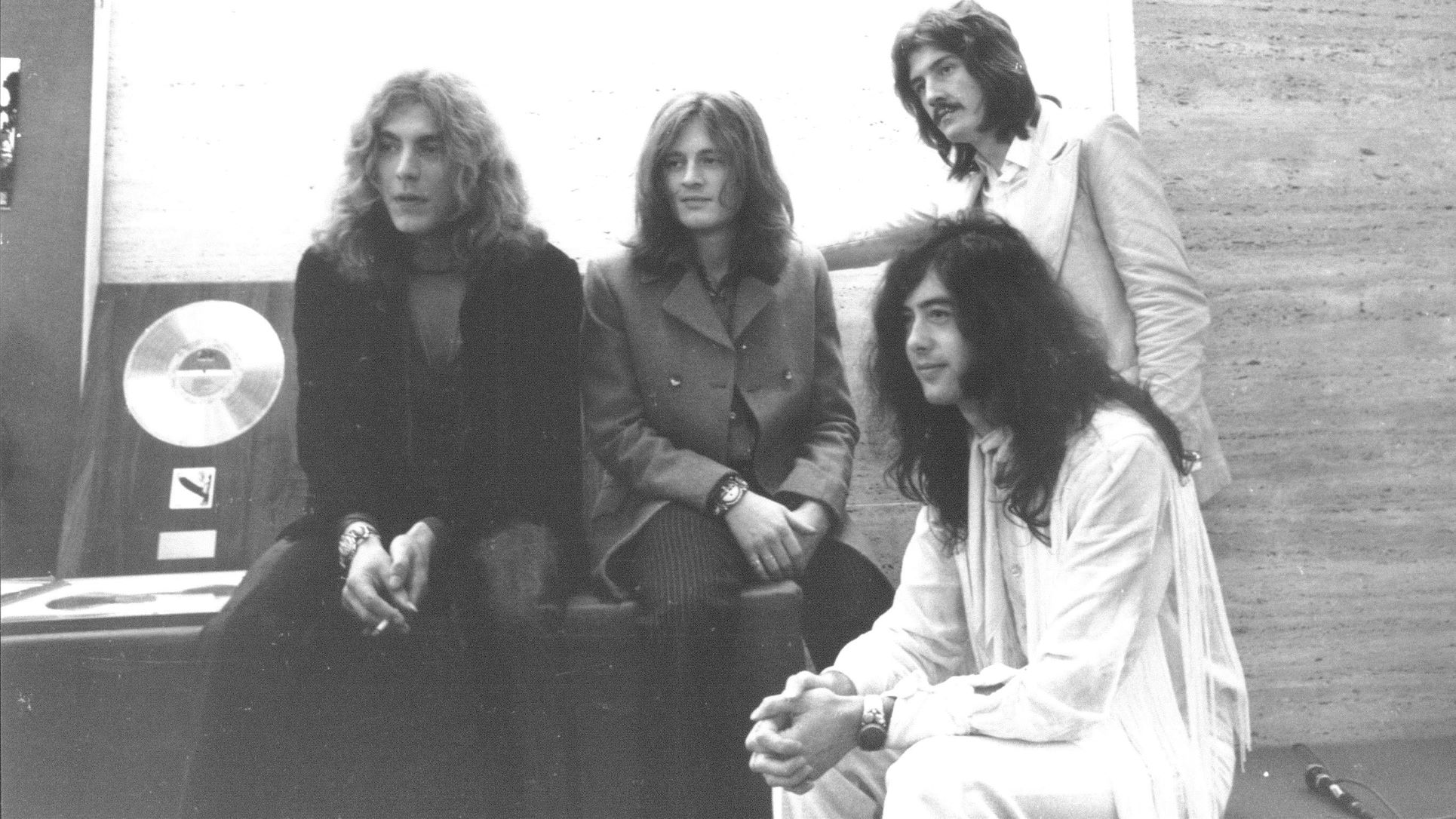

At the end of May 1969, while their first album was charting at number 10, Zeppelin ended their second U.S. tour with two sold-out nights at New York City’s Fillmore East. Following the second show, Atlantic Records held a party for them at the Plaza hotel, where they were presented with a Gold record for Led Zeppelin. It was also here that Jimmy Page was told that Atlantic was itching to get a new album in stores before the end of the year.

Stung into action, Page ordered the band back to the studio after the party. Fortunately for all concerned, Led Zeppelin’s music was evolving at a faster rate than ever, and often onstage. Many of the spontaneous jams they’d created on their U.S. tour had taken on a life of their own and become full-fledged songs. They included “What Is and What Should Never Be,” “Ramble On” and “Whole Lotta Love,” which had surfaced on tour as part of an extended improvisation during “As Long As I Have You,” a Garnet Mimms tune that had been a standout of their set list early on.

These and other songs built on ideas begun in motel rooms and tinkered with at soundchecks and rehearsals provided the foundation for Led Zeppelin II.

Eddie Kramer, the U.S. engineer on the sessions, had worked with Jimi Hendrix on Electric Ladyland the previous year. “I got a phone call from [Zeppelin’s] office in New York,” he recalls. “‘The boys are in town, and they want to know if you want to help put this record together.’” Kramer recalls “scrounging” recording time for them in any studio he could, and even recording some of Page’s electric guitar solos in hallways.

“They were all over the place,” Kramer says of the sessions. “Some things were done in London, some were on the road. They had this huge trunk of tapes [from the various sessions].” Kramer notes that, once the tracks were assembled, he and Page completed and mixed them in just two days, on August 29 and 30, at A&R Studios in New York “on the most primitive console you could imagine.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Regardless of how it was made, Led Zeppelin II successfully evoked gutbucket electric blues, amped up beyond anything previously heard and laced with potent traces of psychedelia. “The goal was synesthesia,” Page said. “Creating pictures with sound.”

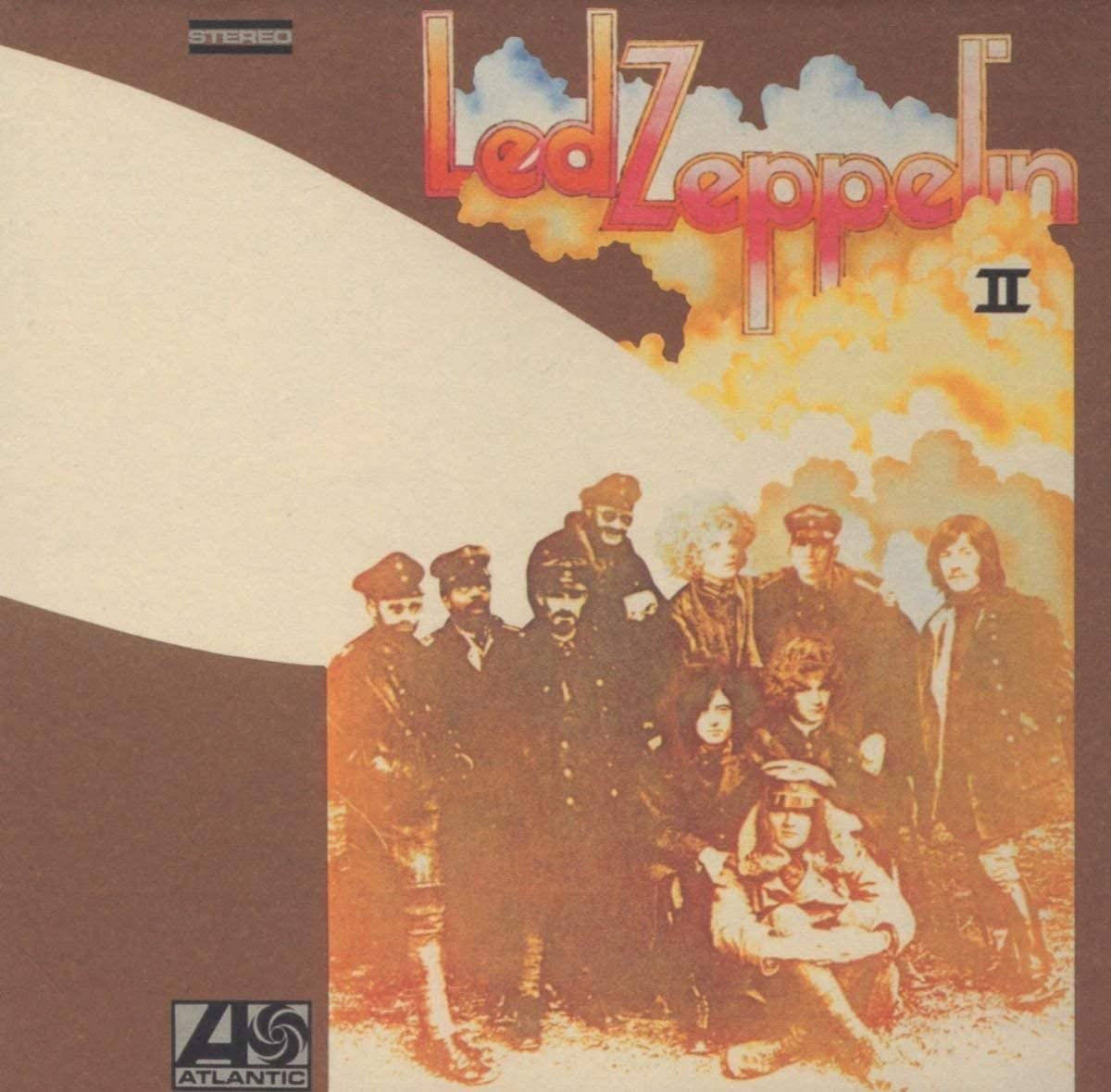

Released in October ’69, Led Zeppelin II put the group at the top of the charts. With U.S. advance orders of half a million, it was the biggest-selling album in America that year, deposing the Beatles’ Abbey Road from number one and keeping the Rolling Stones’ Let It Bleed from the top spot. All told, it spent 138 weeks on the charts and climbed to number one in February 1970.

“LZ II was a marvelous record and so different from the first album,” Kramer says. “With the mixing process, it was an organic thing. We instinctively went for something different, and Jimmy did some really interesting stuff with the sound.”

“Whole Lotta Love”

Page initially came up with the classic “Whole Lotta Love” riff in late summer 1968 at his boathouse home on the Thames in Pangbourne. Some nine months later, in April 1969, it was this song that kick-started the sessions for Led Zeppelin II at Olympic Studios in Barnes, London.

The song originally took shape around Page’s killer three-note riff, with its E power-chord conclusion and a descending chord structure that made use of a backward echo, an effect that the guitarist had first used on a Yardbirds recording session with producer Mickie Most. Further overdubs were added at A&M Studios in Hollywood. Final work on the track took place at the marathon mixing session at New York’s A&R Studios on August 29 and 30.

“The whole thing with Jimmy was that we liked to leave in little mistakes and ad libs and things,” Kramer recalls. “It added to the whole vibe. So on ‘Whole Lotta Love,’ we left in that cough at the beginning. Then, on Robert’s ‘Way down inside’ vocal part, we found we had a leakage from track eight, a previous vocal track that we couldn’t seem to lose. So Jimmy and I cranked up the reverb and left it in. Big mistake? Happy mistake!’’

Lyrically, the song borrows wholesale from Willie Dixon’s “You Need Love,” recorded by Muddy Waters in 1962. Dixon successfully sued Zeppelin for royalties in 1985. Following an out-of-court settlement, the bluesman’s name was added to the song’s writing credits. At the song’s fade-out, Plant also threw in lines from Dixon’s “Shake for Me” and “Back Door Man.”

“Whole Lotta Love” received its live debut on Zeppelin’s second U.S. tour during a show at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco, on April 26, 1969. The band also played the song on its support gig for the Who in Columbia, Maryland, on May 25, 1969. In June 1969, Zeppelin previewed it on a BBC session but didn’t play it again until 1970. From then on, the song became an integral part of their set.

“What Is and What Should Never Be”

“What Is and What Should Never Be” is another song Led Zeppelin initially worked on in April 1969 at Olympic Studios. Further overdubs took place in June at Mayfair Studios and Groove Studios in New York City. Page had by then switched from his Fender Telecaster to his Gibson Les Paul for recording and performances. The track is notable for the flanging effects and stereo separation on the fade-out.

“I’d done a lot of that type of panning and phasing with Jimi Hendrix on Are You Experienced and Axis: Bold As Love,” Kramer says. “‘What Is and What Should Never Be’ had all the phasing and panning, which we loved to do. It typifies the whole vibe of Led Zeppelin II.’’

A version of the song was recorded on June 24, 1969, for the BBC at the broadcaster’s studio in Maida Vale, London. During the session, DJ Brian Matthew interviewed Page and asked him to select a track representative of the forthcoming album. His choice? “What Is and What Should Never Be.” Explained Page, “It’s got a bit of everything.”

Along with “Whole Lotta Love,” “What Is and What Should Never Be” was broadcast on John Peel’s BBC Radio One Top Gear show on June 29, a good four months before the album’s release. It was premiered live during Zeppelin’s appearance at the Laurel Pop Festival in Maryland on July 11, 1969, and performed again in Framingham, Massachusetts, on August 21. It was then inserted on the late-1969 U.S. tour and played at every gig through 1970–’71 up to the U.S. tour in June 1972.

“The Lemon Song”

“The Lemon Song” was cut at Mystic Studios in Los Angeles in May 1969, with further overdubs applied in August at A&M Studios in Hollywood. “It was such a small studio,” recalls Chris Huston, the studio engineer at Mystic. “I was very impressed with Jimmy’s ability to double-track and create the sound he wanted first time, every time. What you hear is the product of a lot of spontaneous chemistry in their playing. We did the tracks live, with Robert Plant standing in the middle of the room with a hand-held mic. You can hear that in ‘The Lemon Song’ where Plant sings ‘floor, floor, floor.’ That echo was recorded in real time.”

Though originally credited to Led Zeppelin, “The Lemon Song” borrowed heavily from Howlin’ Wolf’s “Killing Floor.” ARC Music, the copyright holders of Wolf’s song, reclaimed the tune in 1972 in an out-of-court settlement. For a short period, U.K. copies of Led Zeppelin II listed the track as “Killing Floor,” credited to Chester Burnett (Wolf’s birth name). Later copies listed it as “The Lemon Song

“Thank You”

“Recorded at Morgan Studios in London in June 1969, Robert Plant’s emotional love song to his wife brought out the best in him and provided one of his finest vocal performances. Elsewhere in the arrangement, John Paul Jones excelled on Hammond organ, and Page complemented it all with some delicate picking using his ’67 Vox Phantom. The song’s chord structure bears a resemblance to the Traffic song “Dear Mr. Fantasy,” and some of its lyrics draw from the Jimi Hendrix track “If 6 Was 9.” “Thank You” also references Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me” with its “mountains crumble to the sea” reference.

Led Zeppelin debuted “Thank You” at Birmingham’s Town Hall on their January 1970 U.K. tour. The song stayed in their set through 1970–’71, acting as a spotlight for Jones’ keyboard solo. It was used as a marathon encore on the 1972–’73 tours, after which the band deleted it from the set.

“Heartbreaker”

“Heartbreaker” was cut at New York City’s A&R Studios in May 1969, with additional work done at Atlantic Studios, also in New York. It’s another integral part of the recorded Led Zeppelin canon and a perfect platform for Jimmy Page to display his guitar virtuosity. “For me ‘Heartbreaker’ is a stand-out,” Kramer says. “The solo was genius Page.’’

A long-standing stage favorite, “Heartbreaker” was added to Zeppelin’s set during their European dates in autumn 1969 and made its premiere at Scheveningen, Holland, on October 3, 1969. It was performed along with “Immigrant Song” at Zeppelin’s bill-topping appearance at the Bath Festival in 1970 and throughout the rest of their dates in 1970 and ‘71. “Heartbreaker” became part of their encore for the U.S., U.K. and European and Japan tours of 1972–’73 before being returned to the main set as a medley preceding “Whole Lotta Love” for the 1973 U.S. dates. In concert, Page was known to stretch out his solo to include sections from “Greensleeves” and an instrumental passage based on Bach’s Bourée in E minor.

“Living Loving Maid (She’s Just a Woman)”

This is another track from the Morgan Studios sessions of June 1969. Page played his Gibson Les Paul to knock out what the band always considered to be something of a production-line filler. However, this tight, hook-laden song found favor on the radio as the B-side of the single “Whole Lotta Love.” When that tune finished its chart run in the U.S., radio DJs flipped the record over and began playing “Living Loving Maid,” eventually making it an A-side, after which it climbed to number 65 on the Billboard chart. The track also became a favorite of U.S. FM radio stations, where it was frequently preceded by “Heartbreaker,” as on the album.

Remarkably, some early U.K. pressings of Led Zeppelin II misprinted the title as “Livin’ Lovin’ Wreck (She’s A Woman).” “Livin’ Lovin’ Wreck” was actually recorded by Jerry Lee Lewis and can be found on the B-side of his 1961 single “What’d I Say,” released on the Sun Records label. This anomaly created a much sought-after rare Led Zeppelin II pressing.

Page has been quoted as saying the band never really liked “Living Loving Maid,” and thus the song never received a full public airing. Plant slipped the first line of the song into “Heartbreaker” during a March 1970 performance in Hamburg, and he sang the opening line in jest at the group’s Earls Court gig on May 24, 1975, no doubt disappointing fans who expected to hear the song. In a surprise move, Plant performed it on his Manic Nirvana U.S./U.K. solo tour set in 1990, turning it into a rousing encore with a mock Beach Boys arrangement.

“Ramble On”

“Ramble On” was laid down on the run at Mystic Studios and Mirror Sound in L.A. in May 1969, and at New York City’s Groove Studios and Juggy Sound in June. Plant’s lyrics reference J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings as the song slips from quiet, mournful passages into an uplifting chorus. As such, it’s vividly illustrates the light-and-shade dynamic that would characterize much of Zeppelin’s best work.

Page’s overdubbed interweaving lick on his Les Paul is an early attempt to create the sort of guitar army assault that would become his trademark. Kramer gives credit to Jones for his nimble bass work and notes how the band members connect so well throughout. “You can pinpoint certain things on the track,” he says. “It’s the whole band looking into each other’s eyes.’’

Surprisingly, Zeppelin never gave a full performance of “Ramble On,” though on the spring 1970 U.S. tour, Plant threw in lines from the song during “Communication Breakdown” and “Whole Lotta Love.”

“Moby Dick”

John Bonham’s monster percussion showcase took shape on Zeppelin’s second United States tour, where it was known as “Pat’s Delight” in reference to the drummer’s wife. The recording took place at Mystic Studios in May 1969, with further work performed at Mirror Sound in Los Angeles and Mayfair Studios in New York City. The track was mixed at A&R in New York City. “‘Moby Dick’ was a bit of a job piecing and editing performances from two different studios,” Kramer recalls. “Whenever I hear it, I think of the job that took, but it’s Bonzo, and he was the best.’’

The riff part of the song can be traced back to the Sleepy John Estes track “The Girl I Love She Got Long Black Wavy Hair,” which Zeppelin recorded at a BBC session on June 16, 1969. It also echoes the 1961 Bobby Parker track “Watch Your Step,” which the band had rehearsed early in its existence but never performed live. For the 1990 Remasters box set release, Page merged this studio performance with “Bonzo’s Montreux” from Coda to create an amalgamated Bonham drum presentation.

“Moby Dick” was first performed live on Zeppelin’s autumn 1969 U.S. tour and stayed in the set on every tour until 1977 (although it was not played at every single show). It developed into an excessive 20-minute showcase which provided the other band members with a much-needed break from performance. By 1975, Bonzo was incorporating a “Whole Lotta Love” riff segment played on electronically treated kettle drums. On the 1977 U.S. tour, the song was aptly renamed “Over the Top” and used the intro riff of “Out On the Tiles” rather than the “Moby Dick” theme.

“Bring It On Home”

“Bring It On Home” was the product of on-the-run visits to studios during Zeppelin’s second North American tour in 1969. It included recording at Mystic in Los Angeles and a session on May 10 at R&D Studios in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. The latter studio, referred to as the Hut, played host to a vocal and a harmonica overdub.

Although “Bring It On Home” was originally credited to Page and Plant, its intro is a blatant rip of Sonny Boy Williamson’s 1963 arrangement of “Bring It On Home” – another Willie Dixon composition – which was issued on the Chess album Real Folk Blues. In 1972, Dixon successfully sued Zeppelin for use of the song, and future releases listed him as the song’s sole creator. Following the intro, on which Plant plays harmonica, the song snaps into action via a riveting Page riff and Bonham’s and Jones’ rhythm. A rough mix recorded at Atlantic Studios on July 24, 1969, surfaced on the 2015 extended Coda album.

Zeppelin performed “Bring It On Home” on their autumn 1969 U.S. tour and retained it for their 1970 itinerary. In concert, the song developed into a lengthy piece, with a terrific Page/ Bonham guitar-drum battle. It was revived briefly for the 1972 U.S. tour as an encore (as can be heard on the album How The West Was Won) and re-used on the 1973 U.S. tour as an opening sequence riff link to merge “Celebration Day” with “Black Dog.”

Buy Led Zeppelin II here.

Buy Mick Wall’s When Giants Walked the Earth: A Biography of Led Zeppelin here.

Check out Dave Lewis’ incredible Led Zeppelin books here.