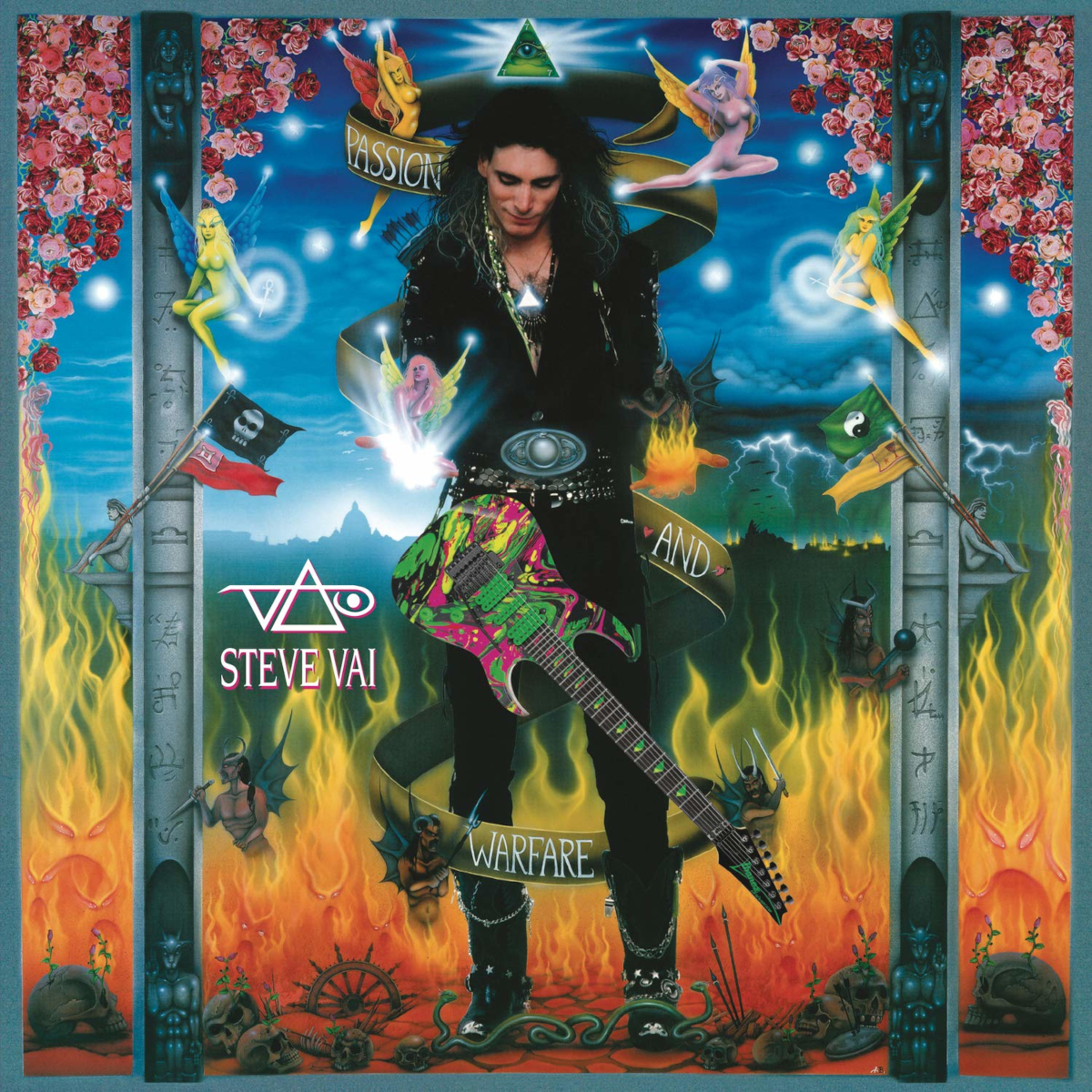

“I Actually Thought It Might Well Be a Dismal Failure”: Steve Vai Discusses the Making of His Groundbreaking Shred Album, ‘Passion and Warfare’

“Steven, I think you’re wrong about that,” said David Coverdale. “This is a brilliant record, and you’re going to be very surprised at the reaction”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The following appeared in the March 2020 issue of Guitar Player

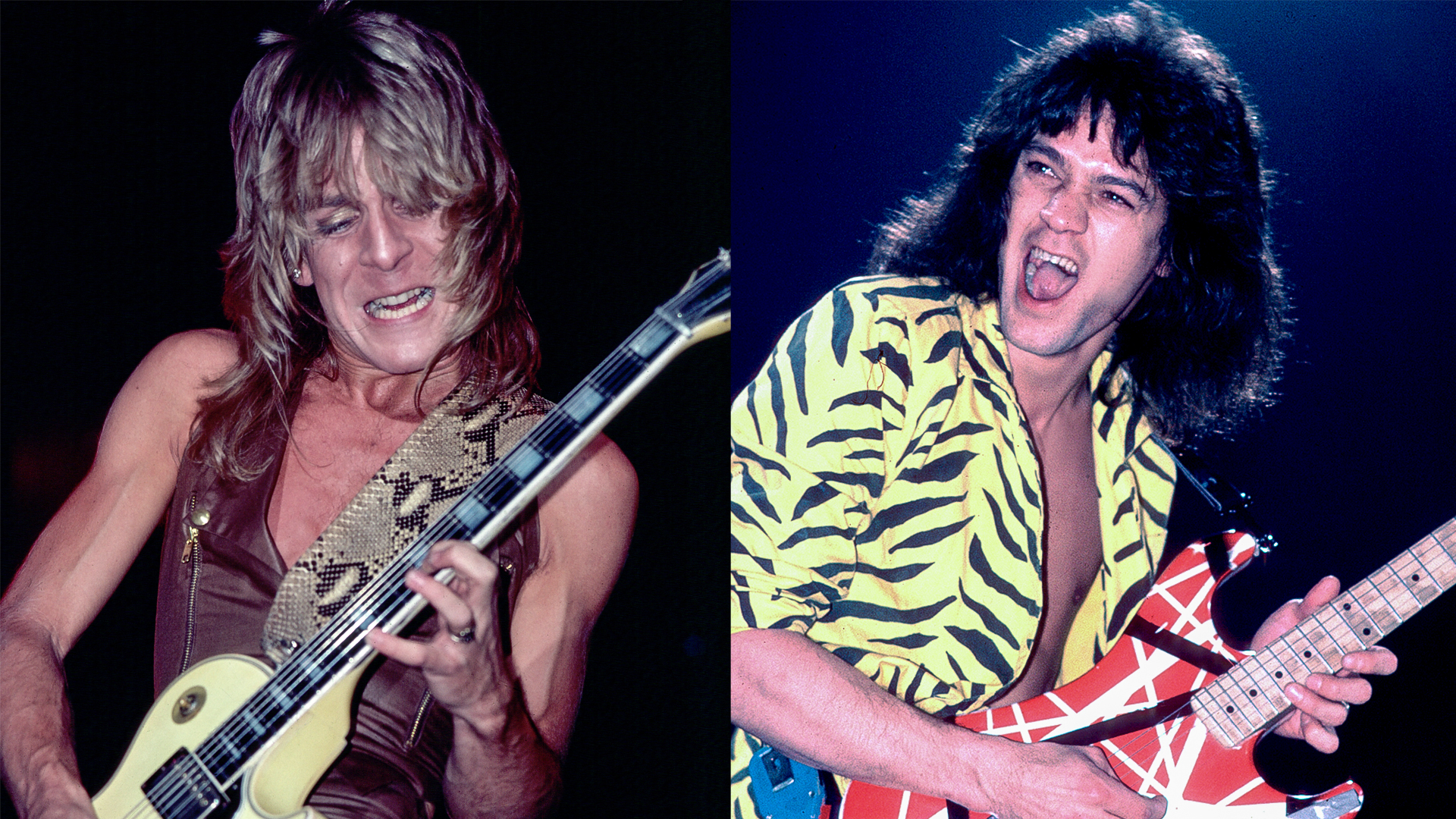

In the pantheon of shred gods, three names instantly come to mind: Eddie Van Halen, Yngwie Malmsteen and Steve Vai. It’s perhaps not a coincidence that Vai replaced EVH as sideman to David Lee Roth and Yngwie as guitarist in Alcatrazz. Few people could take over from either of those giants, let alone both of them, but Steve Vai is unlike any other guitarist.

His prodigious talent was recognized at an early age by Frank Zappa, who first employed him to transcribe guitar parts, and then included him in his band. For Guitar Player readers, the appearance of Vai’s solo track “The Attitude Song” on the first flexible Soundsheet disc in the October 1984 issue was a cataclysmic moment. For Vai, the disc and the release of his debut album, Flex-Able, that year marked a major shift in his status in the guitar playing community.

At the dawn of the ’90s, following stints with Roth and Whitesnake, Vai unleashed Passion and Warfare, his second solo album and one of the few truly essential landmark albums of the shred era. Decades later, it remains the benchmark for guitar virtuosity, not only for Vai’s incredible playing but also for its memorable melodies and stunning psychedelic production.

“For the Love of God,” in particular, has become a must-learn rite of passage for shredders, and Vai has featured it in nearly every live set since the album’s release. Ask Vai what it was like to make the album, and he recalls it as a happy period. “I was in a state of bliss all the time,” he says. “There was no time that it felt like work. To do something other than making music might feel like it would require work, but the process of making the music made me feel completely free. It was a long time coming, after years of working with everyone from Zappa to Whitesnake.

“As you can hear from listening to the album, that record has virtually nothing to do with those bands. You can imagine that music was bubbling up inside me for years, and I was waiting, waiting, waiting to birth the album. I had no expectations. I wasn’t projecting myself into the future and trying to placate an audience or count my money, you know? I had zero fear whether it was going to be a success or a failure. It didn’t matter one bit.”

Vai had begun planning the album as early as 1982 but put it aside when the Roth gig came along and didn’t return to the project until he and the singer parted ways in 1989. By then he had built the Mothership, his own 1,600-square-foot studio, at his home in the Hollywood Hills, where the album was recorded. He had also acquired several pieces of gear that were put to use on the album, including the Eventide H3000 Harmonizer, which can be heard all over its tracks.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

With unlimited freedom to create, Vai pulled out all the stops, creating a sonic tapestry appropriate to Passion and Warfare’s metaphysical themes. Deep into new age philosophy at the time, Vai fasted for 10 days during the album’s creation, during which time he recorded “For the Love of God.”

Given that he was in such a singular state of bliss, it’s not really a question where the passion of the album’s title comes from. Vai bears this out. “The thing that was at play was my passion,” he says. “I was enjoying the present moment.” But what about the warfare? Where is that part of the title reflected in the work? Vai laughs. “Well, I was a very intense young man,” he says. “I took everything very intensely, and perhaps that’s where the warfare comes from. I don’t have warfare in my life.”

Then again, perhaps the title reflected his belief that the album might not connect with the public. “I actually thought it might well be a dismal failure,” Vai attests. “It didn’t sound like Satriani or Eric Johnson, you know? The first person I played it for was David Coverdale while I was in Whitesnake. I said, ‘I don’t know what’s gonna happen with this record. I expect it’ll just come and go.’ And he said to me, ‘Steven, I think you’re wrong about that. This is a brilliant record, and you’re going to be very surprised at the reaction.’”

I took everything very intensely, and perhaps that’s where the warfare comes from

Steve Vai

Over three decades on, it’s safe to say Coverdale was correct. Here, Vai discusses the making of his groundbreaking shred album...

It must be difficult to title songs when they don’t have any lyrics. What comes first: the name or the music?

It can be either way around. The name “Erotic Nightmare” came before the song. The entire P&W record happened at a time when I was in a very experimental personal stage with metaphysics. I had discovered new age spirituality, for want of a better term. It involved things like the study of metaphysics and everything from dreams to astral projection to numerology and astrology.

At the time, they were all very fascinating to me. Remember, I was working on that album for many years, before I even joined David Lee Roth’s band. I had to put it on the shelf during that time. There was a period when I was living in a kind of commune with friends and my girlfriend from college, who’s been with me for 40 years now. One of my best friends in life, Marty Schwarz, he and I started getting into astral projection and the notion of controlling dreams.

Marty, who was not really a spiritual kind of person, for some reason was having wild astral projections, so we started experimenting with all this kind of thing. We got some wild, scary and fascinating results. We documented them and wrote little stories, and a lot of those stories turned into the songs on P&W.

Did you spend a lot of time sequencing Passion and Warfare’s tracks?

When I talk to some of my friends, like Joe Satriani, he doesn’t get too involved in the sequencing. He leaves it to the producer because he thinks they have good instincts for that kind of thing. But I can’t help but construct the ebb and flow of the record.

The sequencing is very important to me. I don’t second-guess it. It usually comes to me very clearly and very quickly, same as when I’m putting a show together. That listening experience is very important to me. My music is so diverse that there’s a lot of different dimensions to explore on the record. It had to go exactly as I sequenced it. Nothing else would have worked for me.

Let me throw a few of the titles at you for your thoughts. Let’s start off with “Liberty.”

That was one of those dreamscapes I mentioned. It was an anthem as I heard it in my head. At one point we even tried to find a country that might use the song as its national anthem. That’s a good example of an instrumental that perhaps could use lyrics.

“Answers” is one of those tracks where I feel I can almost hear lyrics delivering the melody.

It’s interesting that you should point that out. The rhythm part is a riff that I had in high school that I enjoyed playing. It never had a melody line though. When I started my first band in California, the singer in the band, Sue Mathis, came up with a melody and lyrics, and that was the melody that I ended up playing.

There’s no end to how deep you can go into the performance of the same song over and over

Steve Vai

“Ballerina 12/24.” I’ve always been a fan of Les Paul’s work, and this track always reminds me of him. Was that an intentional nod to one of the original studio masters, or is that coincidental?

I wasn’t really aware of his work on overdubbing until years ago. That came after I sent my suggestions to Eventide and they sent me back a prototype for the H3000 and a patch in there suggested that to me.

For many fans, “For the Love of God” is arguably your signature track. Did it feel like you’d created something significant and long lasting at the time?

To me, all the songs are significant, as they should be for anybody that is making records. You have no way of knowing how the world is going to receive it. I had the melody for over 10 years. I knew that I wanted to do a very long expressive guitar solo. The extent of my expectations was that there might be some other guitar players that might like it because there was so much guitar. At one stage, I thought I might not even put it on the record as it felt overindulgent.

It’s a high-intensity performance. How do you get into the zone to channel that intensity night after night at a live show?

Enthusiasm is what takes me there – connecting with it. Having the state of mind of appreciation that I’m capable of doing it. I play it at virtually every concert that I’ve done. I see it as a privilege to able to perform it. I could never be bored, because, to me, that means you’re not appreciating what you have.

There’s no end to how deep you can go into the performance of the same song over and over. Every time I play it, my attention to every note becomes sharper and finer. I get closer to the notes every time.

“The Audience Is Listening” is the other Passion and Warfare track that everyone knows. Something about the melody always reminds me of Felix the Cat holding his sides with laughter.

[laughs] That’s a good analogy. Some of my melodies can also sound like the voice of the teacher in Charlie Brown as well – that “wah wah wah.” [laughs] Of course, that song is really a piss-take on “Hot for Teacher.” That was a real favorite Van Halen track for me. I didn’t intend to release it, but then thought, Why not?

“Greasy Kid’s Stuff” opens with you listing some details about the mix, including the settings on the Pultec EQs. Was that your way of delineating one take from another that had a different EQ setting?

It was just an easy way to remember what the settings were for that particular take, rather than writing it down. Believe me, there are so many outtakes!

“Love Secrets.” I hear it as a soundtrack to a short movie, although I can’t quite nail down what kind of movie that might actually be.

It was pure stream of consciousness. It was at the pinnacle of the astral projection experiment that we were doing, where I had a couple of wild experiences that I documented. In one of them I was hearing this music that was far beyond what human ears hear. It came in that in-between sleeping and waking state, and it was just like a flash.

Subsequently, after that, I read accounts of other people that had these experiences and I tried to reflect that in “Love Secrets.” It falls way, way short, but it still produced something of the effect.

Order Steve Vai’s Passion and Warfare here.

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.