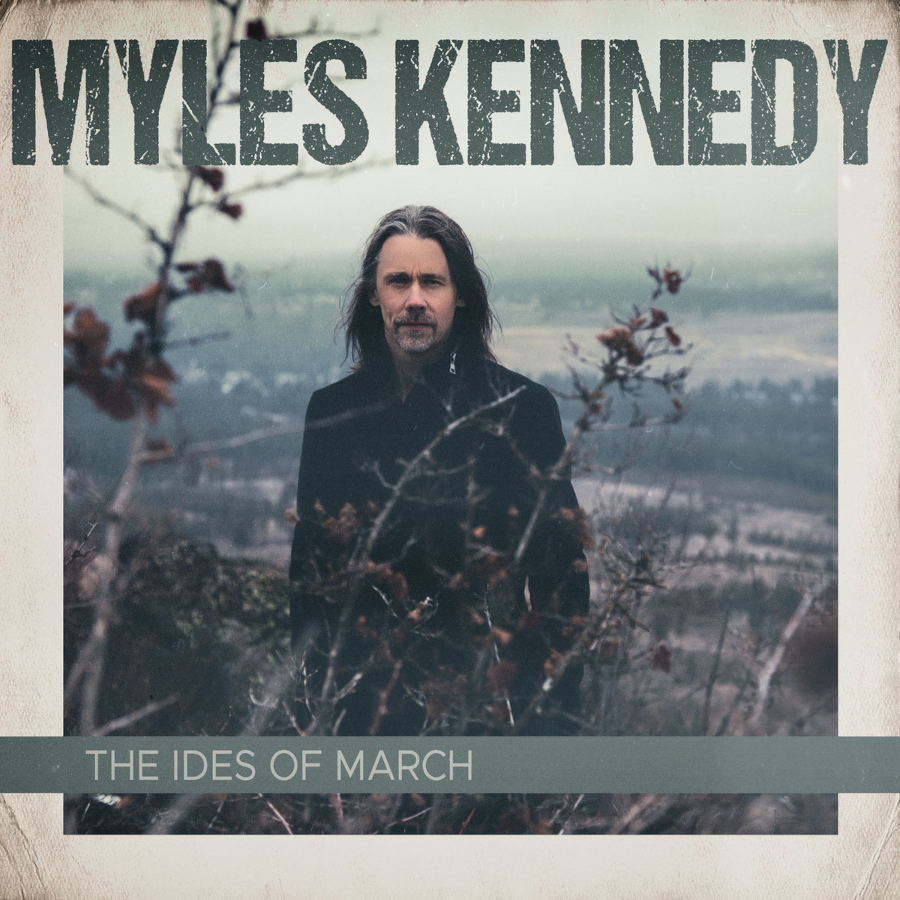

“I Really Wanted to Explore My Relationship to the Guitar”: Myles Kennedy Reveals the Inspiration Behind His Latest Solo Release

The Alter Bridge and Slash singer has the guitar spot all to himself on his album ‘The Ides of March.’

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Myles Kennedy is known for his gigs fronting two of rock’s leading acts, each of which is centered around an avowed guitar star: Alter Bridge, with Mark Tremonti, and Slash featuring Myles Kennedy and the Conspirators.

But in addition to being an in-demand vocalist, Kennedy is also a pretty stellar six-stringer himself. In fact, growing up in Washington, the now 51-year-old saw himself as a guitar player who also did some singing, rather than the other way around. And in his first major band, the ’90s alternative hard-rock combo Mayfield Four, he handled both lead vocals and lead guitar.

In more recent years, of course, the guitar slots in Kennedy’s bands have been well taken care of. And even when Kennedy stepped out on his own with his 2018 solo debut, Year of the Tiger, it was with a more folk-rock-influenced effort that saw his guitar playing function primarily as a rhythm accompaniment to his vocals.

All that said, Kennedy admits that in the past few years, “I really started to miss guitar a lot, especially improvising and lead playing. So I started to rekindle that love. I would sit on my couch for hours every day and just play. And I started to think, Well, on my next solo record…”

Now, that next solo record is here. It’s titled The Ides of March (Napalm Records), and, true to Kennedy’s word, it’s an unabashed electric guitar-centric effort, with his songwriting and vocals surrounded by a blitz of explosive solos, melodic lead lines, bluesy slide licks and high-energy riffs.

For those who think of him as a singer who also dabbles in guitar, well, maybe the truth is actually something closer to the reverse. “I really wanted to explore my relationship to the guitar this time out,” he says. “Because when I was younger, I was the kid who sat in his bedroom all day, every day, trying to be a guitar guy. I was obsessed. I still am.”

When we first listened to The Ides of March, we assumed, given your status as a singer, that you were mostly playing rhythm guitar, and not the lead parts as well. But it’s all you – the rhythms, the leads, the slide work.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

[laughs] I started as a guitar player, and it’s so funny how life has worked out. If you would’ve told me when I began playing guitar and playing in bands locally, “One day, you’re going to be this guy who’s more known as a singer,” I’d have said, “No way!” Because I was really shy.

I didn’t want to sing. But once I started writing songs, because I lived in a community with a finite number of other singers and musicians, I thought, Well, I guess I’ll just learn to sing and do this myself. And I don’t want to say I abandoned guitar playing, but my focus shifted dramatically.

Were you mostly self-taught, or did you take lessons? You seem to have a pretty solid grip on theory and technique.

I was a sponge. I studied with this guy named Joe Brasch, who’s a local guitar hero in my community. I’d go in every Tuesday or Thursday, and it was the highlight of my week. I learned all that stuff from him – a lot of theory, understanding how to hit the changes, things like that. And later on, I studied two years at a community college, taking nothing but music classes. I learned how to arrange for big band and the history of jazz, and I played in jazz bands. And so, yeah, I was kind of a freak. [laughs] I loved it so much.

I learned how to arrange for big band and the history of jazz, and I played in jazz bands

Myles Kennedy

Diving into the new record, it’s clear that, from a lyrical perspective, you really focused on our current cultural moment – the pandemic, lockdown, societal ills, divisions among people.

I remember, in February 2020, I was touring with Alter Bridge and I was talking with my manager, who told me, “We’re supposed to get a solo record done later this year.” And I thought, Oh, that’s going to be interesting! Because we were supposed to go to Asia, and we had all this other stuff going on. So how was I going to write this record? Little did I expect but, about three weeks later, the world essentially shut down, so I had plenty of time to write, and I took advantage immediately.

We got off the road in late February; I gave it about a week and then I started working. And this was as everything started to shut down, and all this information was coming out and there was a lot of uncertainty. It was, for lack of a better word, concerning. You know, “Where are we going?”

The world essentially shut down, so I had plenty of time to write, and I took advantage immediately

Myles Kennedy

And so a lot of these songs were written early on in that process, and they’re definitely a reflection of what so many of us were feeling in those uncertain times. But I didn’t have any agenda, because I’m not that guy. Other people can do that, I can’t.

I look at the world, and I reflect on how it’s affecting me emotionally, and my family, and then I put it into songs. But when I hear these songs now, it’s pretty palpable. You know, if I listen to “The Ides of March,” you can hear the uncertainty and…I don’t want to say fear, but definitely concern.

That one in particular is so epic in terms of the arrangement, songwriting and guitar playing. And it climaxes in a great, dramatic solo. It’s certainly the centerpiece of the record.

That, to me, was the most important track to get right. I felt like I didn’t have a record until that song was done. The genesis of it – that melody and the chord sequence – came to me in a dream. I recorded it on my phone and then came back and revisited it, and I thought, Oh, this could be something cool. And it’s different from a lot of the things I do.

The genesis of it – that melody and the chord sequence – came to me in a dream

Myles Kennedy

So it was a journey. It took a long time to find each one of those parts and build it. The whole thing took about six months total. And the part that was the most challenging was the coda. It was a lot of, “Is this gonna work? Is that gonna work?” I just kept going back to the drawing board. I wanted it to be uplifting, because when I was writing the song, I felt like the clouds were parting at the end. You could see the blue sky, and I wanted the music to follow the narrative.

There’s also some great slide playing throughout the record. The first single, “In Stride,” on which you play a resonator guitar, would be an example. What’s your history with slide guitar?

I’ve had the luxury of getting to jam with Gov’t Mule a few times, and standing onstage next to Warren Haynes is mind blowing. He’s like the Jedi master. But the first person that led me to pick up a slide and try to understand how it worked was Bonnie Raitt.

Back in the early ’90s I was in an R&B cover band, and her version of “Thing Called Love” was big. So I learned that slide part at the beginning. And from there I just started to listen to different players. Derek Trucks was an influence, obviously.

The first person that led me to pick up a slide and try to understand how it worked was Bonnie Raitt

Myles Kennedy

And another guy who was big for me was Ian Thornley from Big Wreck, who we toured with quite a bit back when I was in the Mayfield Four. Ian is a monster slide player, and he’s the person who turned me on to a lot of different altered tunings.

There’s a song called “Lyla” on the second Mayfield Four record [2001’s Second Skin]. We were hanging out in Ian’s kitchen one day and I was playing it in regular tuning. He said, “Why aren’t you playing that in open G? It’d be so much easier, so much cooler.” I was like, “Oh, yeah. You’re right! Thanks, Ian!”

What gear did you use on The Ides of March?

A lot of this album was informed by older instruments. I’m a PRS guy, and I love PRS, but I would pick up an old Telecaster or an old ES-335, and it got to me somehow in a different way. I really fed off of that on this record.

A lot of this album was informed by older instruments

Myles Kennedy

I’ve been really lucky to acquire a handful of cool instruments along the way, two of which were used a lot this time – a 1958 Gibson ES-335, which I played on a lot of the solos, and a ’53 blackguard Telecaster that I wrote a fair amount of the record on and used to track it as well.

And for slide, I have a 1954 Fender lap steel that’s great, but those single-coil pickups have a lot of hum, which was challenging. I ran it through an Amplified Nation amp, and if we turned the gain up to get it to sing, the buzz would come. So we had to mess around with playing in different parts of the room. It was a real interesting process trying to get that figured out. But I think it sounded great in the end.

How about other amps and effects?

As far as amps go, I have a 1958 Fender Deluxe that has the 5E3 circuit. So many guitar players that I love use and record with that. It’s a simple amp, but when you put a microphone in front of it, it just works. And my producer, Elvis [Michael “Elvis” Baskette], had a nice 1974 Marshall combo. If I was going to have one side of the mix be the Deluxe, the other side a lot of times was the Marshall.

For effects, I used a few EarthQuaker Devices pedals, including one of their delays. And for overdrive I had a Fulltone Full-Drive 2 and a Klon clone. In fact, on “In Stride,” to give the secret away, I’m playing a newer National Resonator into a Klon clone into the Fender Deluxe. Now, I understand there are purists who will say, “Wait a minute, you put an overdrive pedal in front of a Deluxe?” ’Cause that’s a big no-no. But it worked, so we were like, “Well, you know…”

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.