“I was the first guy at Studio One, and I played with everybody who came through. Bob Marley was a little boy when he cut his first tune there”: Ska, reggae guitar king Ernest Ranglin on the origins of the ‘skank’ style, and the early Jamaican scene

In a 2014 chat with GP, the pioneering six-stringer discussed his tonal preferences and guitar teaching philosophy, and the most beloved – and enigmatic – guitar in his collection

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The following interview with Ernest Ranglin was originally published in Guitar Player in 2014.

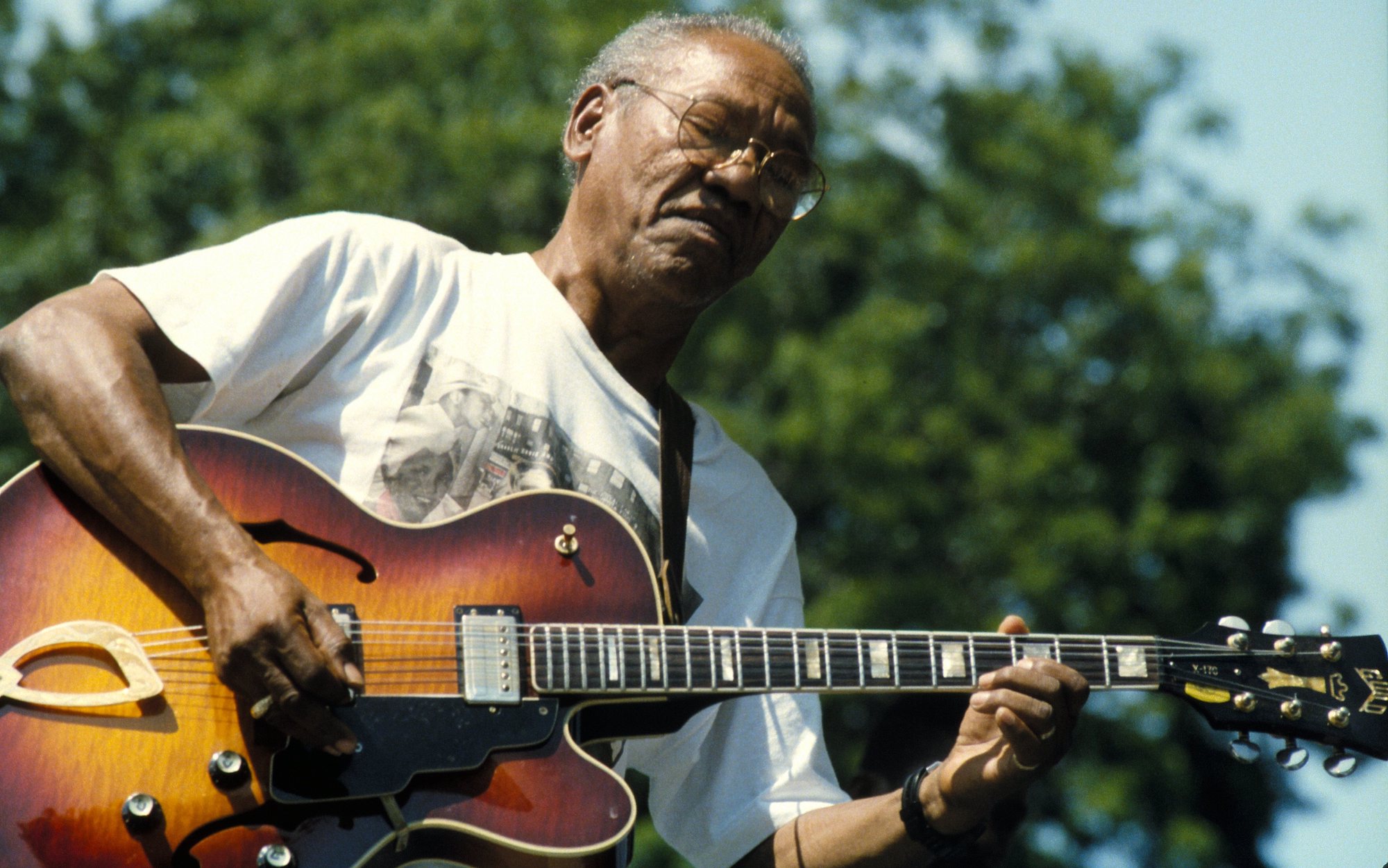

“You have to put in the time,” says Ernest Ranglin about how he developed into such an eloquent guitarist – and the 82-year-old legend knows a thing or two about what it takes to become a master.

Regarded as the architect of Jamaican guitar for his pioneering work with producers Coxsone Dodd (Studio One) and Chris Blackwell (Island Records) in the late ’50s and early ’60s, Ranglin is the godfather of ska, a reggae ruler, and a harmonic maestro adept at weaving jazzy phrases among spacious syncopated grooves. His signature song, Surfin’, ranks among the all-time great guitar instrumentals.

The band Avila has inspired Ranglin’s most recent resurgence. The diverse, international ensemble coalesced at the 2011 High Sierra Music Festival, where GP witnessed a watershed performance. Ranglin’s second disc backed by Avila, Bless Up, picks up where the eponymous debut left off.

Follow On is the kind of Ranglin original that gets festivalgoers giddy – reggae grooves with gobs of jazzy guitar goodness. It bounces like Bob Marley’s Is This Love with Ranglin’s gorgeous chord melodies riding atop the infectious rhythm. Any aspiring young player would be proud to rip like Ranglin’s rapid runs on Jones Pen and Rock Me Steady, and the perilous chromatic sloops on Sivan are simply beyond most mortals.

Can you pinpoint a moment of inspiration that determined your musical direction?

“My influences really started with Charlie Christian. I listened to other guitar players, as well, but I didn’t try to emulate them because I wanted my own style. Charlie Parker and John Coltrane were inspirational, but I didn’t emulate them too much either, because I didn’t want to go so far out as to lose my audience. I try to be commercial and make music that’s accessible.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What did you learn from listening to horn players that all guitarists should investigate?

“The main thing is to actually know what you’re doing. You should have a good understanding of melody and harmony, because that’s the key to creativity. You have to do your homework.”

Could you please detail your plucking approach, and how you developed such dexterity?

“I prefer a heavy pick – any brand, as long as it’s not too small. I use heavy, .014-gauge D’Addario flatwound strings, too, because I don’t bend notes much, and I like a lovely sound. As for plucking, I simply go up and down.

“I wanted to have good speed – especially for solos – so I developed it traditionally. I would pick a scale, play it slowly, and then see how fast I could go. That’s how you develop dexterity. In reality, it takes time.”

Can you explain how you use chromatics to connect and color diatonic lines – which you often play using octaves?

“You don’t just go and do it. You need to work with the chromatic scale for a while, and develop speed in all of your fingers. You have to work at running scales using octaves, too. Then you can start to connect the two techniques the way I do.”

One of your trademarks as a soloist is how far you descend and ascend.

“The guitar offers a wide range of highs and lows. It doesn’t make sense to me to play one region of the instrument. I play it all over, expansively.”

Would you say that you invented the shuffling skank rhythm – like on Sivan?

“Yes. The style came from listening to New Orleans second-line music. But instead of starting the rhythm on the first beat, you start on the second beat. Emphasizing the downstroke on beat two makes that a style all its own.”

What was the Studio One scene like, and how would you describe your role there?

“I was the first guy there, and I played with everybody who came through that studio. [Bob] Marley was a little boy when he cut his first tune there. That was not ska, it was an original blues tune, but ska came from Studio One. Theophilus Beckford did it first on a tune called Easy Snappin’.

“I did my composition Silky at that same session. I wanted it to be on the B-side then, but they didn’t put it out as the B-side. I didn’t even know it was released until about 40 years later when a guy in Japan asked me to autograph a copy of a record in 1990. I saw it was Silky, and I knew that it was old [laughs].”

So you recorded Silky even before Shuffling Bug?

“Yes.”

After that, you went to record for Chris Blackwell’s upstart Island Records label in England. Your ska rhythm informed Millie Small’s 1964 reworking of My Boy Lollipop, and your sound went global. Can you share some gear insights behind your tone on the Studio One and Island recordings?

“In those earlier days, sometimes I used to use a wah. No one did, you know? As for guitars, I still have the little old semi-solid Guild I was using when I went to England. That was when I was beginning to get famous. Then, I managed to buy more Guilds, but I also love Gibson guitars. I have many kinds of guitars, but those are my two favorites. The granddaddy Gibson is the Heritage [acoustic], so I like that guitar – although I don’t have one.”

Do you know the exact model of the little old Guild?

“I don’t really know for sure, because I don’t see any model name on it. It was not brand new when I got it. I bought it from someone at the radio station I worked at in Jamaica around 1958. I’d say the guitar was nine or ten years old, so it was from the late ’40s or early ’50s. I don’t play it anymore, but it’s very special to me.”

I write from my head. When I was young, I heard about a great gentleman who wrote a symphony in his head. That inspired me to write my music that way

There are multiple studio versions of Surfin’ floating around. When and where was Surfin’ originally recorded?

“I recorded that at Studio One for the Studio One label sometime between ’65 and ’66. I re-recorded it in 1996 for Below the Bassline, because I did not get any royalty money from the first recording.”

What guitar did you play on Bless Up?

“I used a modern Epiphone. I’m not sure of the model – I’ve got too many guitars – but it’s a little bigger than a Gibson ES-125. I prefer vintage guitars, because the tonal quality from the pickups and wood sounds warmer. Modern instruments have more of a plywood feeling, but I can still get a good sound. Ninety-five percent of it is how you maneuver, and how you manipulate the pickup controls.”

How do you set the controls to achieve your very pronounced, yet mellow tone?

“I put the toggle switch in the middle to get the sound of both pickups, and then I mix them together until I get the mellow tone I want. I prefer to keep the controls rolled back. I usually set the neck pickup’s volume at about 5, and the bridge pickup between 3 and 4. I don’t like the tone up past 5.”

What rig did you run through?

“I used a Roland Jazz Chorus JC-120. That’s my favorite amp, because it delivers a nice, clean tonal quality. I don’t use effects. I like a natural sound.”

How does the guitar factor into your compositional process?

“I write from my head. When I was young, I heard about a great gentleman who wrote a symphony in his head. That inspired me to write my music that way. After high school, I bought more books to learn music theory. I taught myself to read and write music well enough to compose in my head. I believe it has more of a natural feeling that’s less mechanical sounding than writing with the help of an instrument.”

Do you teach guitar?

“I teach guitar everywhere I go, and my lessons are free. The only time I get paid is when I teach at a music school. When someone asks me questions about the instrument or whatever, I answer them, and if I can show them, I will. That is a part of my life, because I didn’t have anybody to teach me. I couldn’t afford guitar lessons when I was young, so I just want to help whenever and wherever I can.”

What do guitar players really want to know from you?

“Everybody would like to play like how I can play at the moment, but I have to let them know that it’s not really like that. You have to practice the instrument. Some people don’t want to learn the notes, but I don’t like to teach just by ear. I teach by notes, because that’s how I took my playing this far, and that’s how you can help yourself take it further.”

Jimmy Leslie is the former editor of Gig magazine and has more than 20 years of experience writing stories and coordinating GP Presents events for Guitar Player including the past decade acting as Frets acoustic editor. He’s worked with myriad guitar greats spanning generations and styles including Carlos Santana, Jack White, Samantha Fish, Leo Kottke, Tommy Emmanuel, Kaki King and Julian Lage. Jimmy has a side hustle serving as soundtrack sensei at the cruising lifestyle publication Latitudes and Attitudes. See Leslie’s many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, dig his Allman Brothers tribute at allmondbrothers.com, and check out his acoustic/electric modern classic rock artistry at at spirithustler.com. Visit the hub of his many adventures at jimmyleslie.com