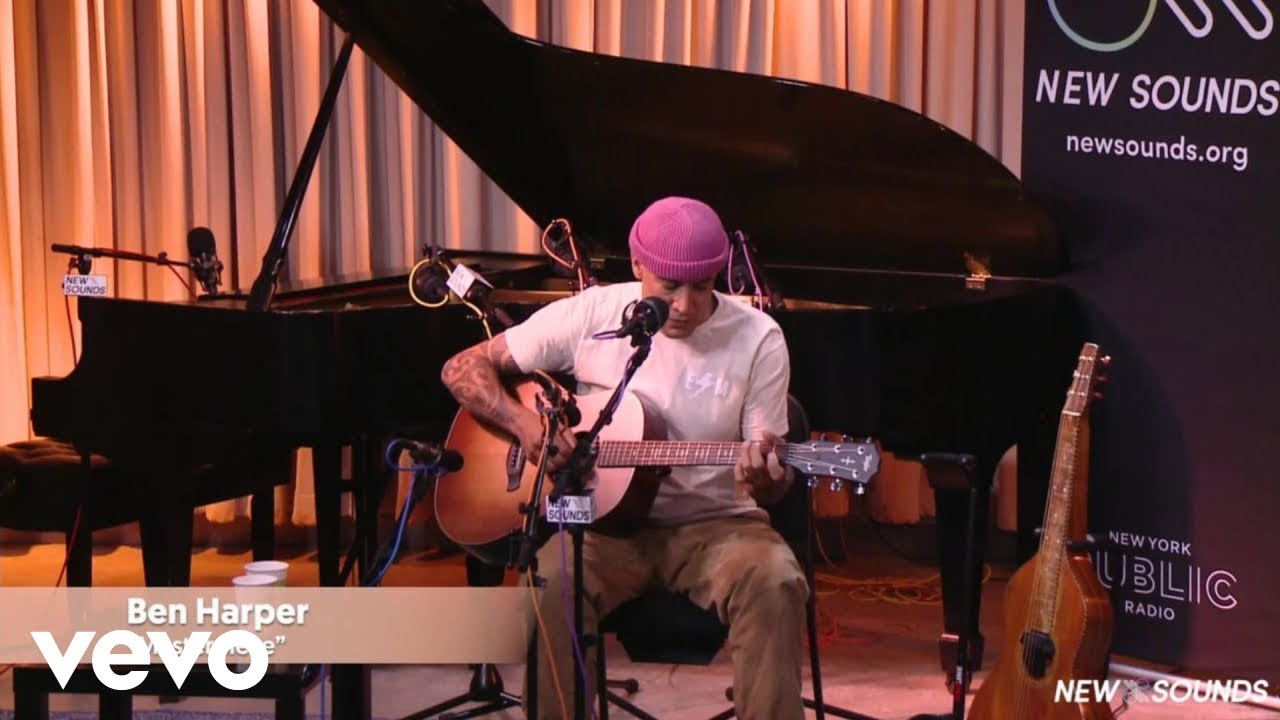

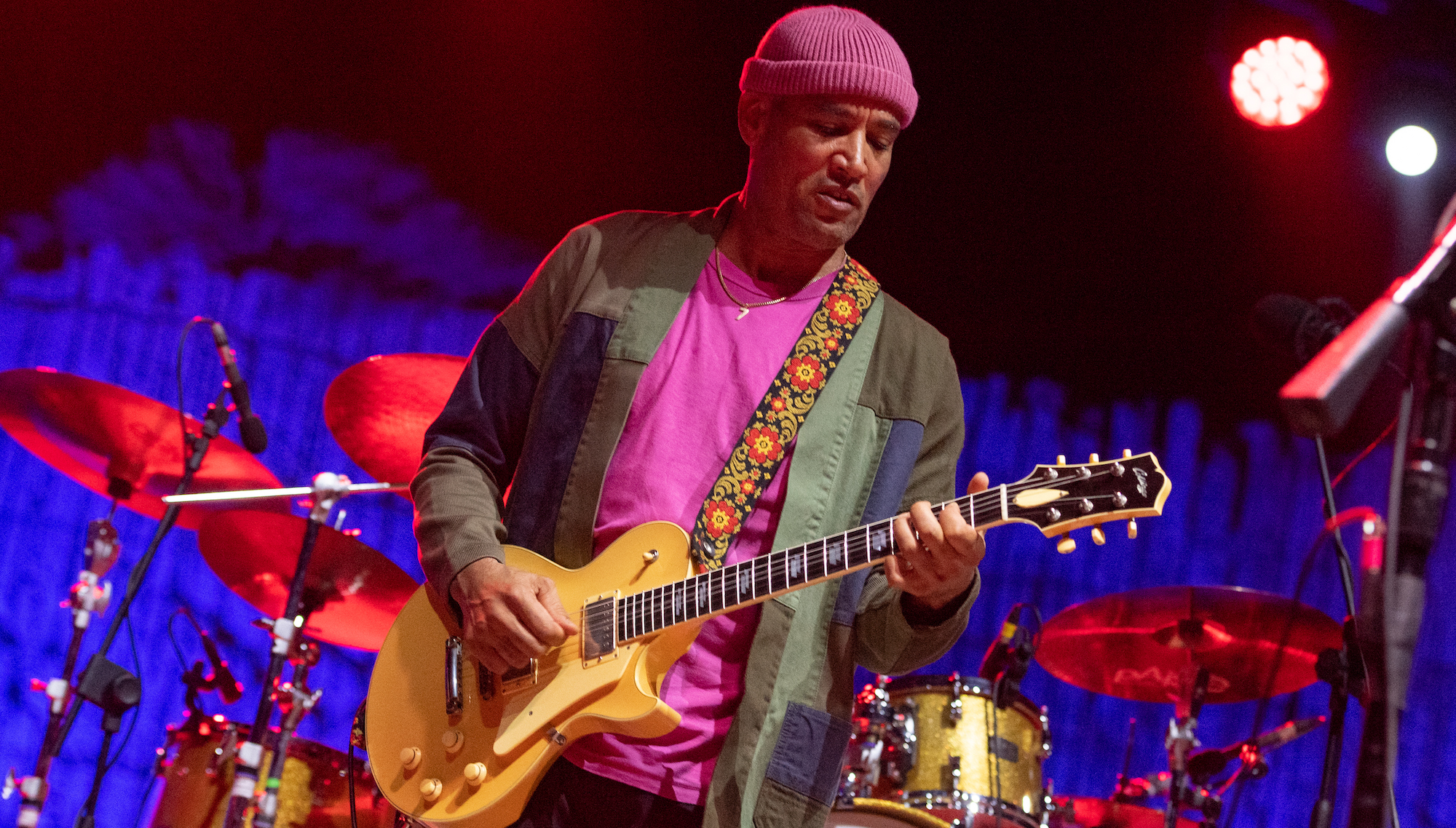

“When I heard David Lindley play the Weissenborn, I went, ‘That’s the most incredible thing I’ve ever heard in my entire life!’”: Ben Harper on playing with Jack Johnson and Harry Styles, and the crazy Martin Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie built

As he celebrates his latest album, Wide Open Light, Harper shares memories of his family's iconic Folk Music Center, what he learned from legends like Taj Mahal, and the Taylor he's “head over heels for”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“At first, I thought every kid had a music store in their family,” Ben Harper recalls. “But I realized when I was young that this place was called the Folk Music Center because it was the center of something special. Not every grandmother can play the entire Pete Seeger catalog on autoharp, dulcimer, and guitar.”

Yale Avenue in the heart of Claremont, California, has a timeless college town quality, with shops that have been there for decades. Founded by Harper’s grandparents, Charles and Dorothy Chase, the Folk Music Center is in its 66th year of operation very near to its original location. Entering the storefront is like stepping into a time machine and landing in the late ’60s to early ’70s.

The walls bear posters for the Claremont Folk Music Festival they presented, as well as the Golden Ring, the venue they ran from 1965 to 1970, which hosted icons like Doc Watson, John Fahey, Reverend Gary Davis, and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. Acoustic instruments from around the world adorn every corner, and some truly historic examples sit behind glass in the museum area established in 1976.

But the Folk Music Center isn’t all about the past. It also offers plenty of new instruments on its racks, alongside the vintage models. None of it is very pricey. Kids come in for gear, lessons, and repairs, and there’s a stage where the staff hosts open mic nights and other performances every week. The Folk Music Center has always catered to real players, social activists, and passionate performers.

“My grandmother could sing as beautifully as any sound you’ve ever heard in your life,” Harper says. “She was the musical spark in the family. She knew the Seegers and the Guthries. My mom inherited that perfect folk voice. She hung out with Hendrix and was getting attention for her chops and songs. But my grandparents needed her here, because she intimately understands this business.”

Ellen Harper is still the one at the front counter when you walk in, asking nicely if she can help you find anything. You can hear her singing voice on the album she did with Ben in 2013, Childhood Home, and read all about the family history in her fascinating 2021 book, Always a Song: Singers, Songwriters, Sinners & Saints. Ben’s R&B-flavored 2022 album, Bloodline Maintenance, is an homage to his percussionist father, Leonard, and his brothers Joel and Peter are musicians who maintain a significant presence at the Center.

Ellen is down to earth and doesn’t mince words. In between ringing up sales at the register and helping a youngster figure out the fixes his axe needs, she takes time to offer real-world insights about running a historic shop in the modern marketplace. On the day I visited, she was joined behind the counter by her granddaughter, who was fingerpicking Dust in the Wind.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It was in Ellen’s office that Harper sat down to discuss the Folk Music Center and his latest album, the acoustic Wide Open Light, which is like a bookend to the album that put him on the map, Welcome to the Cruel World. And as he presented tales about growing up in this down-home musical environment, it was fascinating to think how it all led to his Grammy-winning career.

Did you always embrace your family heritage, or were you a rebel?

“I embraced it from the beginning, but when teenage years hit I was gone, out in the streets. The music was glorious. The late ’80s and early ’90s was the gilded golden age of hip-hop, but I was a player. So, fortunately, I was able to find my way back to the music that was always kicking around my head as a kid while I was striving to create myself.”

You went on to rock out, but it’s interesting how your 1994 debut album was a folk record, as if it was always sitting there waiting to come out.

“It was only sitting there because of being raised in here. When you spend a certain amount of time in an environment like this, it becomes you in a special way. And I’ve had the privilege of watching so many incredible musicians, known and unknown, come in here and put on amazing personal performances, right up to this very day.”

David Lindley lived nearby and is probably the most famous cat for hanging around in here. He lit your fire for Hawaiian lap steel, correct?

“Yes. David would come in here all the time and play the Weissenborns. That was my inspiration. I had heard everybody come in here and play everything, but when I heard Lindley play the Weissenborns, I went, ‘That’s the most incredible thing I’ve ever heard in my entire life! There’s no way I’m not going to try my hand at it.’ My grandfather sold Lindley his first Weissenborn.”

It’s so cool to be surrounded by exotic world instruments, and if there was one guy that could probably play everything…

“It was him.”

How about you?

“David could transform the room on all of it. I can probably transform about three or four minutes on a lot of stuff, like oud and saz and some Indian stuff. But David was different. He mastered them all. He put in 10,000 hours on all of them. I played to my strengths. I put 10,000 in on the lap steel and on writing songs. That was my shit. And then I was off touring quickly.”

Taj Mahal is another otherworldly maestro of instruments from around the globe, and he told me a funny story. He’d been flown in to play the Claremont Folk Festival and was upstairs trying to get some sleep when he heard you playing lap steel with your friends down here, loud enough to make sure he could hear it up there. He was impressed enough to come see, and there you were on the Weissenborn. Is that the way you recall meeting him as well?

“Yeah, that’s how it happened. I had been going to see Taj since I was a kid. Any time he was within a hundred miles, we’d go as a family, like a pilgrimage. We’d close the shop early and go.”

The connections between your family, the legendary players, and the instruments are incredible. Would you detail the story about selling the Pete Seeger/Woody Guthrie guitar?

“Pete and my grandparents were family friends. A guitar wandered into the shop. It was a Martin that had been cut in a way that doesn’t even make sense. It had been sawed, well, straight down the middle.”

Like a sandwich?

“Yes. Someone had opened it up and placed tongue depressors inside to space it out, as an experiment to see what it would sound like.

“So the guitar wanders into the shop, and my grandfather’s first thought is, ‘What a shame, you’ve ruined a great Martin!’ It was a double-0 or a triple-0. My grandfather buys it for a nominal fee, because it’s damaged goods. He hangs it on the wall, and it sits there for a year, two years. Finally, someone makes an offer and my grandfather says, ‘Good riddance, get it out of here.’

I wanted Wide Open Light to feel like you walked into this place and heard me playing guitar

“Pete Seeger comes in looking for Martins, and my grandfather says, ‘Funny, we just had a Martin in here.’ He gave him the description. Seeger says, ‘Was that a double-0 or triple-0, lined with tongue depressors all the way around to hold it together?’ My grandfather says, ‘Yeah.’ Pete says, ‘That was Woody Guthrie’s guitar. Woody and I did that in his shed.’” [laughs]

Oh no!

“Yes. And my grandfather called the guy to say, ‘Hey, we need that guitar back.’ But by then – and this is odd because it’s not really what you do – the guy who bought it said, ‘Well, sorry. I just called Martin.’ He had already found out because Martin had registered it as Woody’s. He knew what he had.”

That guitar should be in the Martin Museum. Whatever happened to it?

“It should be somewhere like that. I suppose it would be in our museum here if it was still around.”

How did your deep connection to the Folk Music Center inspire Wide Open Light?

“I wanted Wide Open Light to feel like you walked into this place and heard me playing guitar. I wanted to make a record that was stripped down. I didn’t want the perfect sound; I wanted the perfect take. I tried to keep it raw and bare-bones.

“A song is enough. Not to take anything away from modern production, but we’ve had a hundred years of it, and I thought it was time to go anti-production. I knew this would be an intimate record, and I wanted to bookend it with acoustic instrumentals, which I’ve been doing since day one. Taj Mahal and David Lindley would transport you by improvising acoustically for 10 minutes, and then start singing a song. I feel it’s important to keep that instrumental flame burning.”

I surrendered and used the live take. I went Needle and the Damage Done on it

Let’s talk about some songs from the new album. Tell me about Heart and Crown.

“The opener is technically influenced by John Fahey. I play it in an open A tuning on a Fraulini made by Todd Cambio in Wisconsin. He’s taken the canon of 1920-to-1930 American instruments and perfected them with an obsession that you rarely see. The guitar that he’s expanded upon here is a Lead Belly–style Stella 12-string. You could spend a lifetime just perfecting the purfling. He makes everything himself, and what he can’t do, like the tailpiece, is nickel silver machined in Germany. He leaves no stone unturned.”

How about Giving Ghosts?

“That’s a live take that I couldn’t beat. It’s played on solo acoustic Weissenborn recorded at the Sydney Opera House on the day I wrote it in 2014. I’ve recorded it in numerous studios, but I wasn’t going to put it on a record until I could beat that. Finally, I surrendered and used the live take. I went Needle and the Damage Done on it.”

What about Masterpiece?

“I wrote that for Rickie Lee Jones, and she did her version turned upside down and on its ear for an album I produced [2012’s The Devil You Know], but I always wanted to do my own version. I realized this is where my version belongs and recorded it on a Taylor Builder’s Edition 517e WHB dreadnought sunburst. The tone is as if a Martin D-18 and a Gibson J-45 had a kid. I fell so head over heels that I used it for every round-neck acoustic part on the new album.”

Yard Sale features Jack Johnson. What’s the story there?

“Jack is playing slack-key acoustic – I’m not sure of his tuning – on a Cole Clark Fat Lady. Mike Valero from the L.A. Philharmonic is on upright bass, and I’m playing my Asher lap steel with a ton of reverb on it in the background.

“When we play live, Jack plays a slack-key solo. On the recording, I took the liberty of overdubbing a solo on a Style 4 Weissenborn. That was my first Weissenborn, and it’s my main one in Style 4. I take the first four bars and then Jack takes the next four.”

How about Trying Not to Fall in Love With You?

“This is the centerpiece of the record. Yes, that’s me playing the piano. I’m like a 10-trick pony in terms of instruments I can play well enough to record something today, and that is the piano Carole King played on Tapestry. They still have it at A&M Studios, and I knew that because of Harry Styles.

“Harry called to see if I could go in there and contribute guitar on a song for Harry’s House [2022] that was not going down without a fight called Boyfriends. Different guitar players had thrown ideas at it, but nothing stuck. He called me up to come have a take, like Steely Dan–style, where they’d call up players to take a swing at a solo. So I was like, ‘Oh shit.’ [laughs]

“What was cool about Harry is he said, ‘Hey, by the way, you know that acoustic guitar you had on your first few records. It sounds like a Martin.’ That’s why he’s where he is – because he really knows. ‘Can you bring that guitar?’ I told him absolutely, but I had given that guitar to my daughter, and she had taken it to school with her in New York. Then I realized that she happened to be home on holiday. She wouldn’t leave that guitar in her dorm.”

Did she bring it?

“Yes! I had been playing Harry Styles when he was in One Direction and giving her tacks to put up their posters. But I didn’t tell her why I wanted her guitar, because I didn’t know if I was going to make the track. But she grilled me, and when I told her it was big, she intuitively knew, because that’s her guy. She fell on the floor – boom! And I ended up making the track. That mahogany Martin 00-18 from the ’50s that I played on Walk Away, Waiting on an Angel, and Another Lonely Day is the guitar I played on Harry Styles’ Boyfriends.”

And lastly, what's the story of Thank You, Pat Brayer?

“Pat is a legend around here in this region called the Inland Empire, and he is one of the best living songwriters. He gave me my first gig and strongly believed that promoting music from this region was the most important thing in the world. I just wanted to shout him out on this closing instrumental featuring the mandocello, which is like a freaking foghorn with strings. It’s the most haunting, spooky, coursed-stringed instrument in existence.

“While I do believe that the album is enough, and everybody is going to stake their own claim in the artform, I’m also a firm believer that there’s got to be somewhere else to go to expand the long-play medium.

“There are so many bad-asses that come through this music store every day, whether they play sitar, tabla, doumbek, oud, sarod, sarangi, hurdy-gurdy, and on and on. I’d like to utilize a day in this music store to make a record: Set up a recording rig with a great engineer and record the day as people come in and out. I’d capture it on video too, to mirror the experience.”

- Ben Harper's Wide Open Light is available to purchase or stream now.

Jimmy Leslie is the former editor of Gig magazine and has more than 20 years of experience writing stories and coordinating GP Presents events for Guitar Player including the past decade acting as Frets acoustic editor. He’s worked with myriad guitar greats spanning generations and styles including Carlos Santana, Jack White, Samantha Fish, Leo Kottke, Tommy Emmanuel, Kaki King and Julian Lage. Jimmy has a side hustle serving as soundtrack sensei at the cruising lifestyle publication Latitudes and Attitudes. See Leslie’s many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, dig his Allman Brothers tribute at allmondbrothers.com, and check out his acoustic/electric modern classic rock artistry at at spirithustler.com. Visit the hub of his many adventures at jimmyleslie.com