All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Before it was alternative rock, it was post-punk, and before that it was garage rock.

For a brief period in the early ’80s, however, the preferred nomenclature was college rock, and the undisputed kings of the scene were R.E.M.

“Sometimes terms can be such funny things,” says Mitch Easter, the North Carolina-based producer and musician who guided the sessions for R.E.M.’s first four recordings.

“College rock – we never took that one seriously. We just thought, Oh, college stations are playing the music? That’s good. It wasn’t something we really bothered ourselves with.”

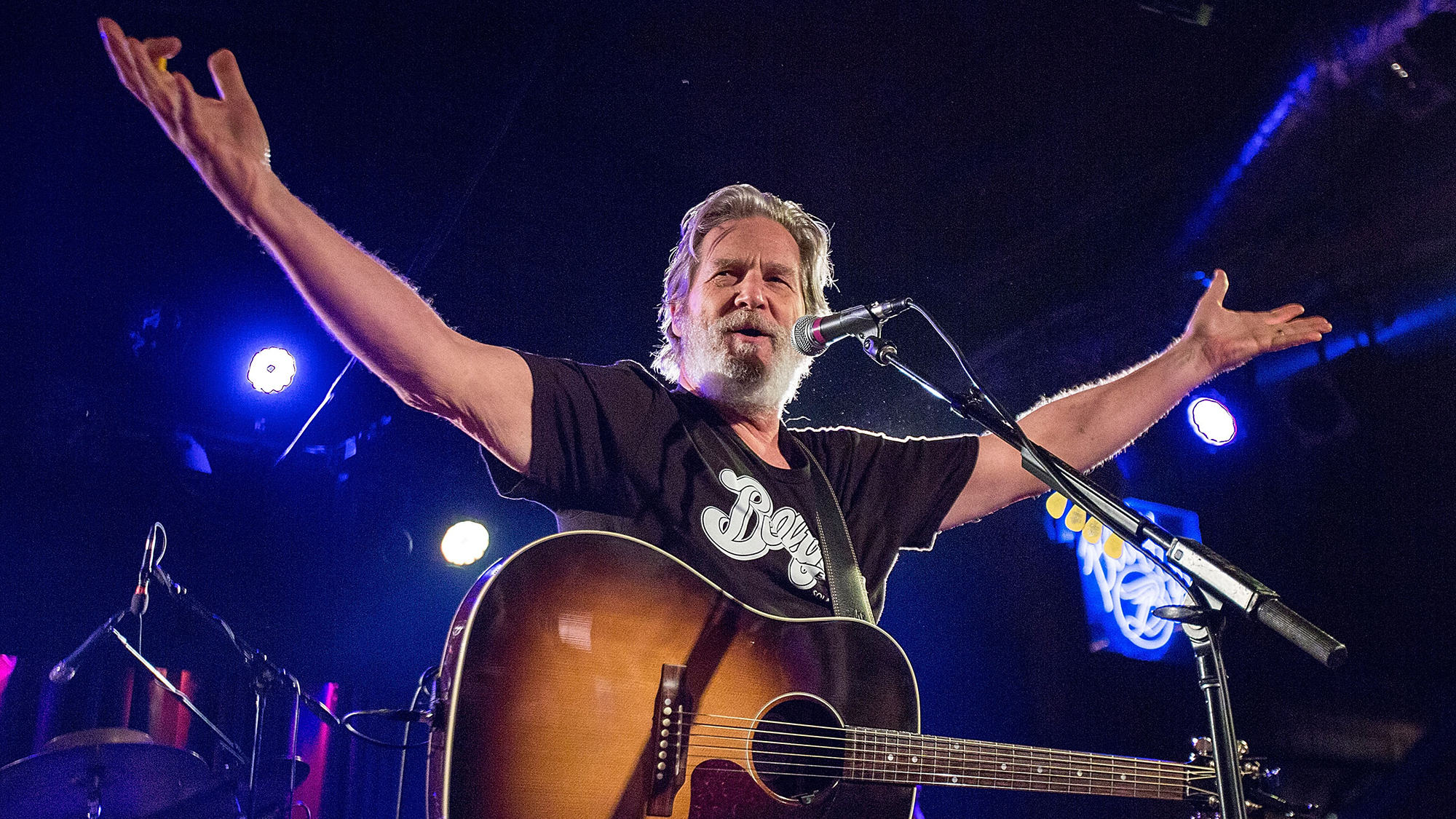

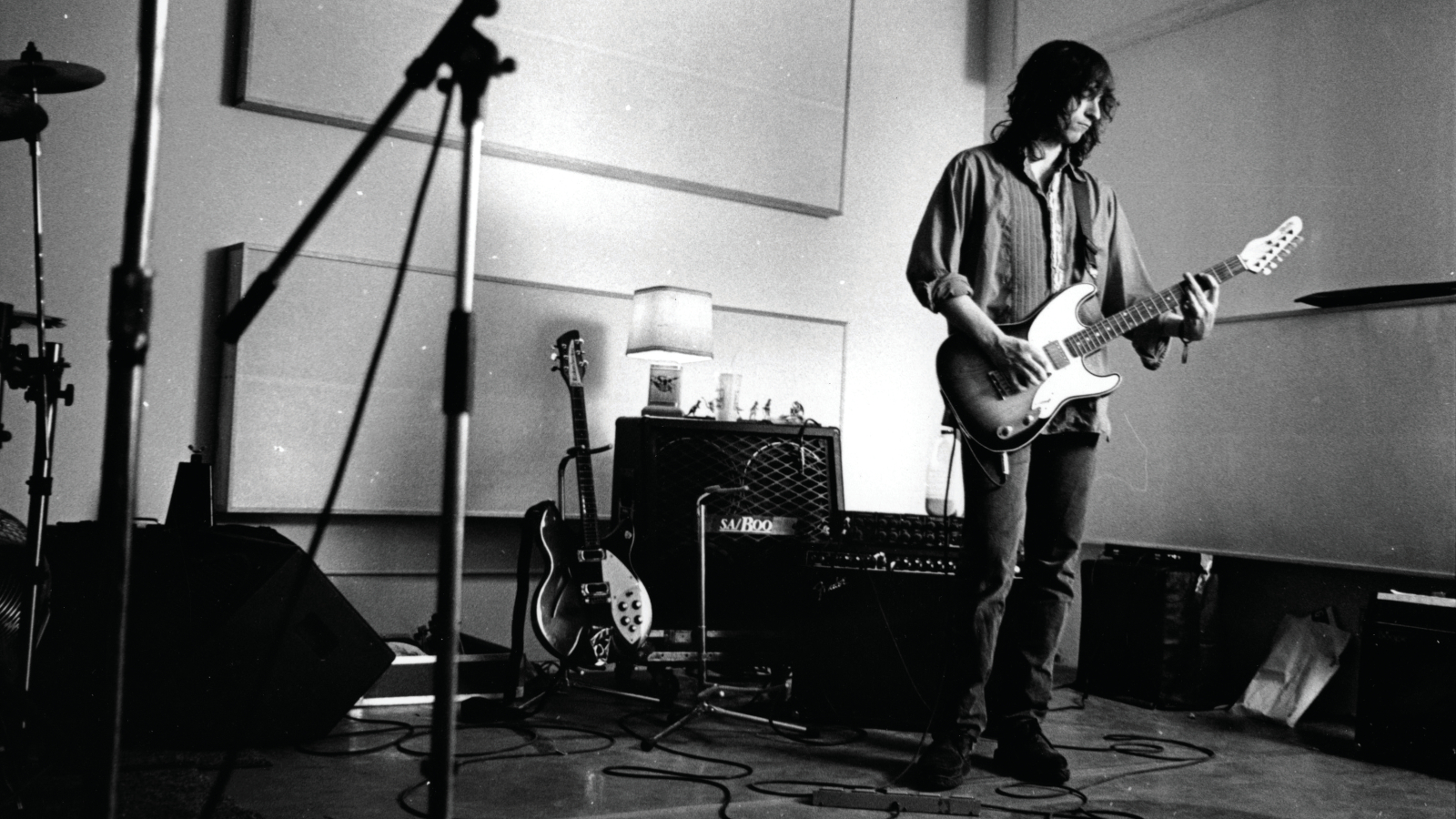

By 1980, Easter was already something of a happening music figure in and around his hometown of Winston-Salem. He had played electric guitar in a number of local bands, some of them featuring his childhood pal Chris Stamey, who would go on to achieve indie success as a member of the dB’s and as a solo performer.

That same year, Easter eyed a move into production, so he converted his parents’ garage into a small recording space and dubbed it the Drive-In Studio, offering super-low rates as an enticement to young talent.

College rock – we never took that one seriously. We just thought, Oh, college stations are playing the music? That’s good

Mitch Easter

“I had 16 tracks,” Easter recalls. “It was the beginning of the indie studio scene, and a lot of small places only had eight tracks, which is perfectly legit. But I wanted to leapfrog that and go into what I considered to be big-time pro recording.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“We had a simple console, a handful of microphones and two compressors, and I also had a two-inch 3M tape machine from a studio in Atlanta. The Drive-In was pretty new when R.E.M. came in. I had recorded three or four bands there by then, but I was still puttering around and getting it figured out.”

Only together for a year at the time, R.E.M. – guitarist Peter Buck, singer Michael Stipe, bassist Mike Mills and drummer Bill Berry – were growing out of the blossoming music scene of Athens, Georgia, and Easter quickly recognized they were different from many of the groups of the day.

“A lot of bands simply wanted to fit in, but R.E.M. always wanted to be themselves,” he says. “I guess a correct way of putting it would be ‘cocky.’ They were like, ‘We rule. Here we come, so get out of the way.’

“It wasn’t so much a careerist mindset; rather, it was their insistence on pure artistry. They meant it. When I first heard them, I thought, Yes. I know what to do with this. This is going to be great.”

When I first heard them, I thought, Yes. I know what to do with this. This is going to be great

Mitch Easter

Easter produced R.E.M.’s first single, 1981’s “Radio Free Europe,” released on the tiny, Atlanta-based Hib-Tone label.

A year later, he recorded the band’s debut for I.R.S. Records, the five-song EP Chronic Town.

For the group’s first full-length album, 1983’s Murmur, and its follow-up, 1984’s Reckoning, operations shifted to Reflection Studios in nearby Charlotte, where Easter assumed co-producing and engineering duties with his old friend Don Dixon.

“I.R.S. insisted on us using 24 tracks for the albums, and Reflection was a great studio,” Easter says. “Don had worked there a lot, so we were a good match. He’s a good musician and a really good recording guy, and he improved the outcome of everything we did.”

The importance of those four recordings cannot be overstated. By distilling the essential elements of garage rock, post-punk, country and even folk into their own special concoction – one that was by turns spooky and engaging, enigmatic and fiercely direct – R.E.M. created a sound that seemed to exist in a previously unchartered world, and they provided inspiration to countless young bands to follow suit.

“To me, they were always in the grand tradition of rock bands

Mitch Easter

Over the years, and while working with a succession of different producers (Joe Boyd, Don Gehman, Scott Litt, Pat McCarthy and Jacknife Lee), the band pulled off something rare and magical in the annals of music, opening up their sound enough to crack the mainstream while retaining their idiosyncratic ambitions.

“I’ve always been a bit surprised at some of the musical analysis of R.E.M.,” Easter says, “because to me, they were always in the grand tradition of rock bands.

“When they came out, perhaps some of the young people who heard them didn’t know garage rock. At the time, even a band like the Sex Pistols, who used to be considered so bold, now sounded like a classic band in many ways. So to hear Peter Buck, he sounded different than what everybody else was doing.

“I guess there’s a lot of reasons why R.E.M. shot ahead. I’m just glad that I was able to be a part of it.”

Could you expand on what first struck you about R.E.M. and why you thought they were special?

Well, the first thing I should say is, I really liked them personally. We had a good time just talking and stuff. But they struck me as the kind of band that could really do the thing. A lot of bands were cover bands, and if they wrote songs, they did so tentatively.

R.E.M. had a different mindset. They weren’t doing cover tunes on weekends at frats. Their attitude was, “We’re a real band. We write our own songs.” At the time, especially in our area, that was different. And, of course, musically, they were good. I didn’t have to tell them how to play. They knew their music.

What were your initial impressions of Peter Buck as a guitarist?

I just appreciated the fact that he was distinctive. It seemed like guitar players were a dime a dozen, but Peter had an identifiable sound, and not the least of that came from his equipment choices.

He played a Rickenbacker with these old, heavy flatwound strings, and I think that made him play a certain way – more deliberate and clear. And I don’t mean in terms of distortion; I mean musically clear.

It seemed like guitar players were a dime a dozen, but Peter had an identifiable sound

Mitch Easter

You have to mean business when your guitar fights back like that. I thought it was great. I’d heard enough distorted fifths already, so I was delighted to hear somebody do something else.

Which Rickenbacker model did he come in with at first?

He had a blonde 360, and then he got the black one that everybody knows. Sometimes he would use my guitars. We’d be working on a track, and I’d say, “You know what would be great? In the chorus, maybe try out this Fender 12-string of mine.” That’s how the 12-string crept into some of their stuff.

What amps was Peter using at first?

He had a Fender Twin, and that’s what we recorded with. I remember when we were doing “Pilgrimage” at Reflection Studio in Charlotte, the Twin was in the shop. [“Pilgrimage” was recorded prior to Murmur as a “test” for I.R.S. Records.]

I didn’t have anything with me, but there was a Kasino solid-state amp in the studio, so we used that, and it sounded great. I think some people might faint knowing that we used this little 25-watt solid-state practice amp, but it had a really nice sound. There were oddball things like that.

For Murmur, he still didn’t have his amp back, so he used my Ampeg G-15. That amp and the Kasino are what’s on Murmur. When they came in to do Reckoning, he had his Twin back. But if you’re a distinctive-sounding guy like him, you sound like yourself no matter what.

Peter could do more with his rhythm playing than a lot of two-guitar bands. Did he ever try out what we might call conventional solos?

He would say that he didn’t know how to play solos, and he was like, “And I don’t care.” Which I thought was fine. That attitude was in the air with punk.

I mean, I like a good solo, but I’ve heard so many boring ones. If you don’t want to solo, great – do something else. Later, he dabbled a bit, but he never really got into that, and it didn’t hurt him.

Peter had an identifiable sound, and not the least of that came from his equipment choices

Mitch Easter

At the time, journalists applied the term jangle to his sound. Did that ever bother him?

I don’t know. I mean, that word crept in, and it built over the decades. I found it a little bit offensive, because it was always put in contrast to some sort of he-man guitar playing that was highly predictable.

But I have discovered in recent years that the word has had a total rehabilitation, because when I talk to young people who come into the studio now, they think the word is totally cool.

I don’t know what Peter thought of it. He’s the type of guy who would be like, “I don’t give a shit.”

I feel like that the blame for that word goes entirely back to the song “Mr. Tambourine Man.” Maybe it’s been retroactively applied to the Byrds.

Generally speaking, did you do a fair amount of guitar overdubs, or did you mainly go for a live sound?

We always tracked like a band and recorded everything. If something needed fixing, we’d go back and fix it. They’d sit in the control room, and we’d punch in a lot. But a lot of what happened was based on what they did on the floor.

They didn’t make a lot of mistakes; they were an efficient band. We would add stuff, and a lot of that came from me: “This should get thicker here, so play this guitar and we’ll make it fuzzy.”

They didn’t make a lot of mistakes; they were an efficient band

Mitch Easter

There was a bit of a hiccup in the early days when the band tried working with producer Stephen Hague for Murmur. That didn’t go so well, though.

It’s not so much they tried that out; rather, I.R.S. Records insisted they try it out. They did the session with him, and it was a bad match.

He was a modern synth guy, so that was doomed from the start. Plus, he did all that producer stuff, making Bill Berry play every drum part 50 times. When they came back to work with us on “Pilgrimage,” I could tell that Bill’s confidence had been shaken.

I’m sure that Stephen felt like his job was to “clean up these boys” so they can go to the top. Whereas Don and I were a lot more cavalier in our attitude toward working on this stuff. We were going to make records that we liked.

Fortunately, the band was very headstrong and prevailed, and Don Dixon and I ended up doing Murmur. And, of course, I’m proud to say that Murmur is the Dark Side of the Moon of the new-wave era.

I’m proud to say that 'Murmur' is the 'Dark Side of the Moon' of the new-wave era

Mitch Easter

In regard to Peter’s playing, it’s hard to pick a quintessential track from that time, but his arpeggios and little lead lines in “Wolves, Lower” are exceptional. Did he have all that worked out?

Oh yeah. If you’ve ever tried to play that song, it’s pretty fast and you have to try not to miss any of the notes.

When they came up with that song, I thought, Wow, these guys have gotten better. Peter could just play like that. He could arpeggio the shit out of stuff and not miss a note.

Not since Hilton Valentine [the Animals’ original guitarist] have I heard anybody as perfect at playing arpeggios for four minutes straight without missing a note.

They rocked harder on Reckoning. “Harborcoat,” “Pretty Persuasion,” “Second Guessing” – those are blazing tracks.

I think it just happened. They were always rocking live. When you see footage of them playing pre-Murmur, they’re like a punk band.

When they made Murmur, they weren’t being contrary, but I think they were aware of the clichés they could become, and they didn’t want to do that. I think that they thought, Okay, we love all this punk, but we’re going to make a record that is thoughtful, textured and interesting.

But that took a little work to remind them that they had that instinct, because the Stephen Hague thing had freaked them out about anything that you might do in the studio.

They were prepared to make this live-in-the-studio thing with those songs, which was really going to undersell them. By the time they did Reckoning, their lives were moving faster, and so they just went with it for a while. Not totally, but a little.

On “So. Central Rain (I’m Sorry),” they sound very comfortable putting their feet close to the line of being commercial.

Right. They were semi-highfalutin, but they were highfalutin in a correct way. They had some standards, but they weren’t weird purists. They weren’t unrealistic.

If they got on the radio, that was okay with them, but I don’t think they catered to it. They were very easy for me to relate to because I had the same aesthetics. I don’t hate commercial music at all.

They wanted to check out the universe of playing in a band and doing all the stuff you can do. They just didn’t want to be stupid or clichéd about it, although no doubt, they had times where they acted exactly like Mötley Crüe or something.

They weren’t too pure to do some of the rock stuff, and they weren’t too pure to consider having hits, but they weren’t going to pander to that either.

They were semi-highfalutin, but they were highfalutin in a correct way. They had some standards, but they weren’t weird purists

Mitch Easter

Was Peter experimenting with different guitars on Reckoning?

He had his own Rickenbacker 12-string at that point. On Reckoning, you hear that, but you also still hear my Fender Electric XII.

Of course, the dark secret of Reckoning is that we also used a Scholz Rockman. I love those things. They were a total joke to some people, but I thought the Rockman was very useful in the R.E.M. sonic palette of the day. When you hear that record, you’re hearing amps and a bit of Rockman.

We must certainly talk about the MVP of R.E.M. – Mike Mills. His athletic bass playing was crucial to the brilliance of those songs.

That’s right. Mike’s great. He’s super strong and solid. Back then, he played with a pick, which I loved. It was so good for their kind of aggression.

The band had a real forward movement about them, matched by Bill Berry’s drumming.

Because Mike didn’t just stick to root notes, he could fill in the sound a great deal.

Oh, absolutely. He and Peter really complemented each other. There was always a counterpoint thing that was really great. The lead up to the chorus on “Radio Free Europe,” there’s that ascending bassline – it’s really catchy.

Mike certainly knew how to play. The stuff he did was really good. It was very important to the total thing.

You’ve always been very gracious about the fact they went on to record with other producers. No sour grapes at all?

Well, that’s just because I’m nice as hell. [laughs]

But seriously, I’m so glad I got to work on some stuff that people cared about. They’re one of the biggest bands of all time, and I got to be there. I had some influence on them for a while, and it was fun. I just felt it was great that all of us were getting to do the thing.

Browse the R.E.M. catalog here.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.