“With Each Successive New Record, We Grow Our Own Legacy”: Vivian Campbell Moves Between Last in Line and Def Leppard Without Missing a Step

The Irish-born axeman says Last in Line’s latest album, ‘Jericho,’ is "all about the solos and the riffs and the structures in the songs”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

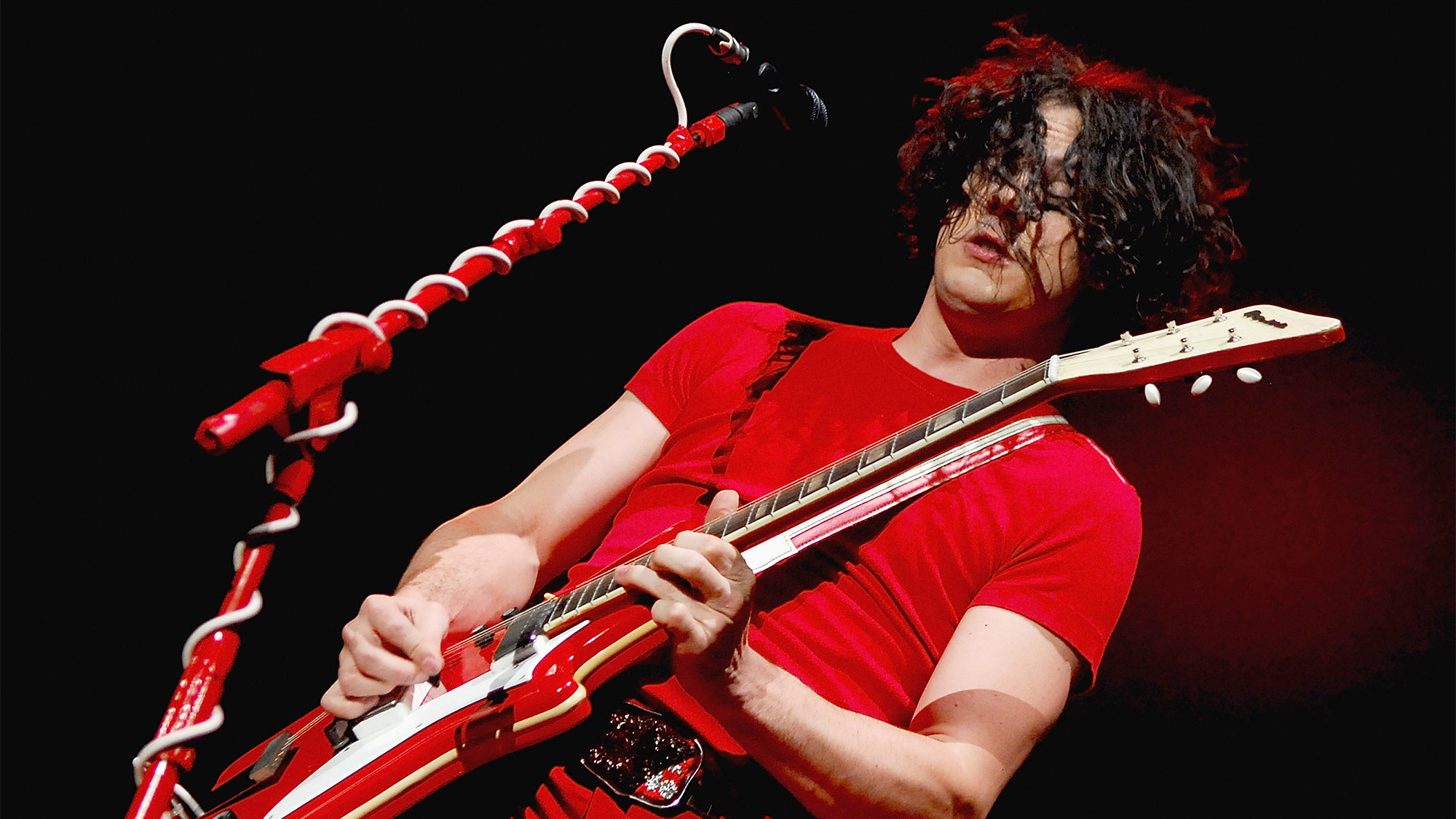

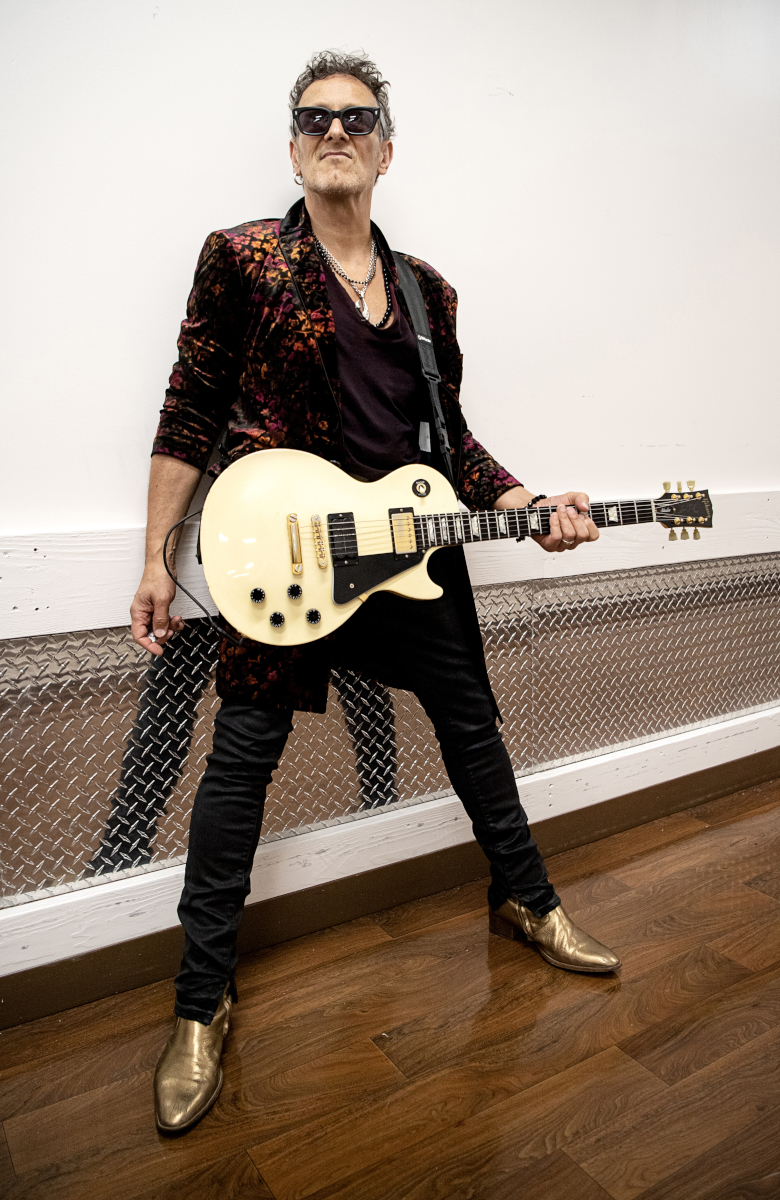

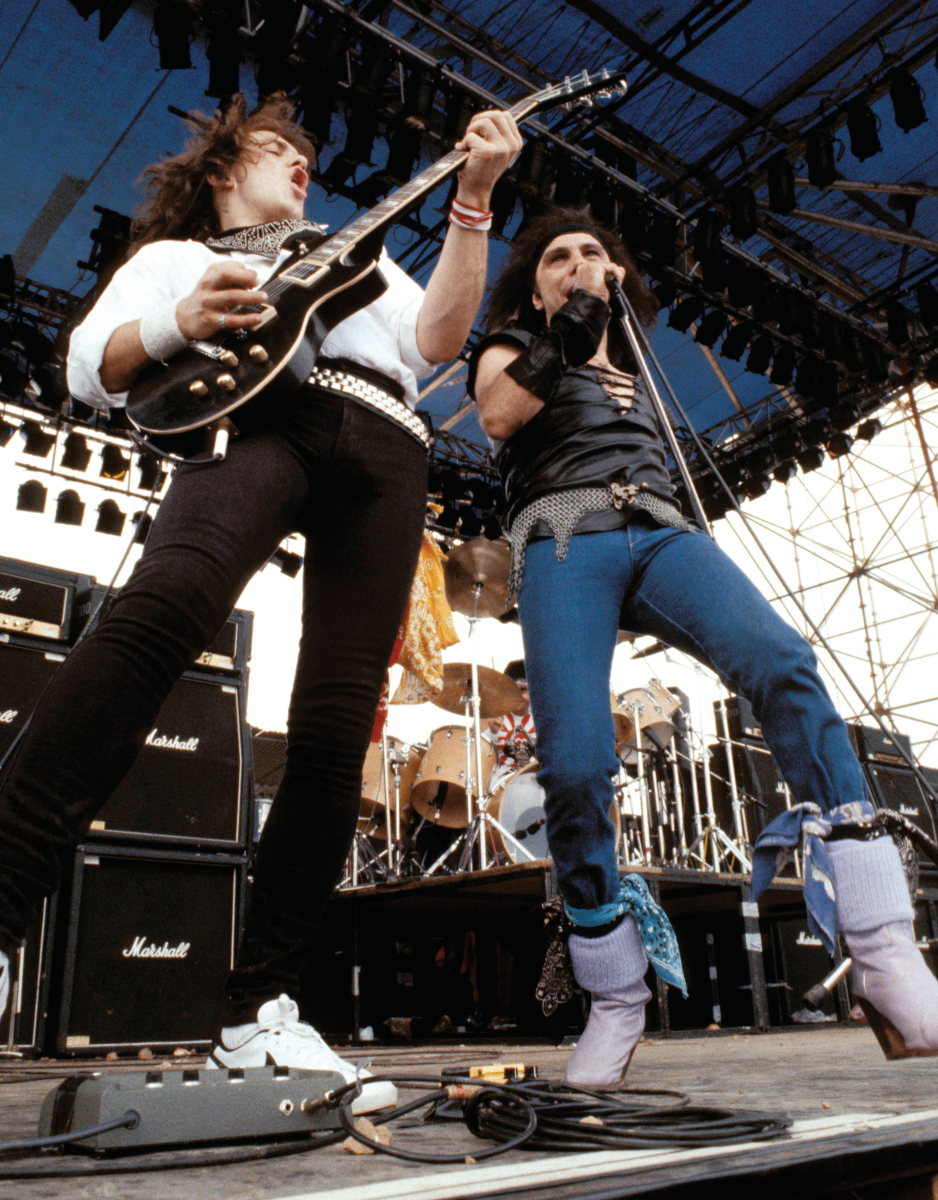

Vivian Campbell was barely 21 years old when he joined the initial lineup of Dio, and he was an integral part of the group’s first three studio albums. Quite a lot has happened since then. The Irish-born axeman was actually seasoned by the time Ronnie James Dio beckoned. A player since he was 12, Campbell was a teenager when he joined Sweet Savage, an Emerald Isle metal band whose “Killing Time” was covered by Metallica. He brought an abundance of chops into Dio and co-wrote tracks like “Rainbow in the Dark,” “Gypsy,” “Caught in the Middle,” “The Last in Line” and “Just Another Day.”

But after touring to support their album Sacred Heart in 1986, Campbell acrimoniously parted ways with Dio, a rift that would not be repaired before the frontman’s death in 2010. The guitarist landed on his feet, joining Whitesnake for a short tenure in 1987 and working with ex-Foreigner frontman Lou Gramm, both with his solo act and his band Shadow King. He played in Riverdogs before being brought into Def Leppard in April 1992 to replace the late Steve Clark. He’s held onto that gig ever since.

Then came 2010. Dio died in May, and that same month Campbell was announced as a member of Scott Gorham’s new Thin Lizzy tour lineup. “Gary Moore is my absolute guitar hero, so when Scott Gorham called and asked if I could be a stunt guitar player for Thin Lizzy in 2010, I can’t even put into words how excited I was,” Campbell told Guitar World.

When the group’s tour wrapped in 2012, Campbell immediately contacted his former Dio bandmates Jimmy Bain and Vinny Appice. “I came off that tour and called Jimmy and Vinny and said ‘Let’s go into a rehearsal room and play!’” With the addition of former Dio keyboardist Claude Schnell and singer Andrew Freeman, Last in Line was born.

Named after a Dio song and album, the group initially featured a repertoire drawn from the first three Dio albums, including the entirety of the band’s 1983 debut, Holy Diver. Not surprisingly, it went down a storm with headbangers still in mourning over Dio’s passing.

Unfortunately, the band encountered some rough sailing of its own: Campbell battled Hodgkin’s lymphoma during 2015, and Bain died in January 2016. His spot was subsequently filled by Phil Soussan, whose résumé included stints with Ozzy Osbourne, Billy Idol and Kings of the Sun.

But perhaps most vitally, Last in Line began establishing its own musical identity, starting with Heavy Crown in 2016, a 12-song set of originals recorded with Bain and produced by Jeff Pilson of Foreigner and Dokken and a Dio member himself during the early and mid ’90s. Pilson was also onboard for the 2019 follow-up, II, and Last in Line maintained a presence on the road when the band members’ schedules allowed.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Now comes the group’s third album, Jericho (earMUSIC), produced by the band itself with engineer Chris Collier. The record was begun prior to the pandemic and worked on in isolation until the quartet was able to get together again in person.

Following 2022’s A Day in the Life EP, titled for its gutsy cover of the Beatles’ epic, Jericho moves the Last in Line story forward another step. It has plenty of the muscular riffs and rhythm-section whomp that was stock in trade for Dio, but it benefits from the years of playing the band members have done since then – plus the combustion of Campbell and Appice with two guys who were not part of their past and, therefore, add fresh elements to the mix. But it’s all worthy of two hands of devil’s horns thrown high in the air.

We caught up with Campbell during some rare downtime at home in New Hampshire, where he moved from Los Angeles a few years ago. Between Jericho, the continuation of Def Leppard’s Stadium Tour with Mötley Crüe, and a new Leppard album, Campbell has every reason to be happy.

“Life is good for me, I gotta say,” he says with a smile.

What did Last in Line set out to do on album number three?

I do think this record shows a bit of a natural progression from what we did on the II album, in terms of pushing the boundaries of the songwriting, and the playing. A big difference between this and a Def Leppard record is we don’t have obvious singles. We don’t have three-minute songs that have great, undeniable hooks – and perhaps we should, but that’s not our mission or goal.

We’re trying to write songs that are very immediate and very driven by the passion that we bring to it, without necessarily trying to aim for something that’s commercially appealing. This is about the solos and the riffs and the structures in the songs. That’s my focus when I write with Last in Line. It’s selfish, y’know? This goes back to the guitar kid I was when just getting my ya-ya’s out.

With Last in Line, do you find yourself channeling the guy who recorded those first Dio albums?

Absolutely. What I don’t honestly think a lot about is the grown-up Viv Campbell. [laughs] And, y’know, I honestly don’t think my style has changed that much. I’m still ham-fisted. I play too heavy with my right hand, and too aggressively, but at the same time that has always defined my style. I think the only thing that’s really changed for me is that I feel more confident about it, and I do feel that it’s refined a bit, but it’s only refined by five or 10 percent. It’s still a very aggressive way to play.

How do you feel you’ve evolved since the Holy Diver days?

With Last in Line, it’s the same, but better, I’d like to think. I’ve refined my style. It’s still manic when it needs to be, but it’s a good manic. I’m trying to eliminate the bad manic, where it just gets messy. In the very, very early Dio days, a lot of it was hit and miss, and a lot of it was luck, to be honest. I didn’t prepare a lot for my guitar solos and I got very lucky and happened to spontaneously get a few good ones.

But there were others that were like pulling teeth, where I was forced to go back and get some structure for a guitar solo before recording it. Nowadays, I save myself the grief by actually having some structure before I start. That’s experience. It’s taken, like, 40 years. I’m a slow learner. [laughs]

What is Last in Line’s creative process like at this point?

We have a spoken rule (well, actually it’s softly spoken): we can bring riffs and grooves and titles for songs, but you don’t come in with, “I’ve got this song I’ve just finished!” We just kick ideas around with each other, and stuff happens or it doesn’t. We will spend 20, 30 minutes jamming on an idea, and if it inspires us we take it further, and if it doesn’t, we say, “Maybe that’ll grow into something at some point.”

It’s a very different thing than what I do with Def Leppard, of course. With Def Leppard we have a very clear path. There’s a lot of discussion about the direction of the record, and a lot of thought that goes into the songs. With Last in Line it’s a much more reckless sort of approach.

Who tends to get things started?

It’s usually myself or Phil with a riff, but sometimes it’s just Vinnie playing drums. He’ll be getting his sound together and getting his levels, and he’ll go into a beat, and I start playing and it takes on a life of its own. Even Andrew sometimes will pick up a guitar and do something, and we’re like, “Oh, yeah, let’s follow that.”

It’s all entirely collaborative. It’s fair to say that of every song on this record – in fact, every song Last in Line’s ever written. That’s part of the fun of this band. It’s loose.

You previewed Jericho last fall with an EP that had a version of the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life” ...which you could say is an interesting choice.

[chuckles] We’ve talked for the last couple of years about doing something that was outside of the genre. We thought it might get a little bit more attention if we did something that was out there. So something like “A Day in the Life” – or any Beatles song – is so iconic, you really ought to not tackle it just trying to do a straight-up version of the original. There’s zero sense in that.

Three albums in, is Last in Line less of a Dio band and more of its own entity?

It’s certainly a lot less than it was at the beginning. With each successive new record, we grow our own legacy, and it’s incumbent upon us moving forward that we mine more and more of the Last in Line albums as opposed to the Dio albums.

At the same time, we’re always gonna be connected to the original Dio band that Vinnie and I were in. That’s a legitimate legacy of ours and it’s something I believe the fanbase wants, even as we move forward.

Is it an albatross?

Some days I look at it as being a burden, other days I look at it as a blessing. I’ll try and be the optimist here and think it’s always going to be beneficial for us to have that connection.

Have you seen the Dio documentary [2022’s Dio: Dreamers Never Die] or read through his memoir?

I have not and I have no intention, to be honest. Let me be delicate about this: It’s Wendy Dio’s project, so I don’t expect it to be a fair representation of what really happened, at least with regard to my era. [Wendy Dio is Ronnie James’ widow.] I tend to not want to have anything to do with Wendy or that organization or that time. It wasn’t a good time for me. It didn’t end well. So, yeah, I don’t like to dwell on that.

It’s an interesting straddle, isn’t it? There’s acrimony, but at the same time you created a lot of important work. Can you step back and allow yourself some pride in what you did?

Absolutely, yes, 100 percent. That’s all I’m celebrating, is the music. It’s very joyous to be able to do that, but it’s completely separated from that whole organization. And it took me a long time to be able to get to that. That’s why I eventually started the Last in Line project: I finally got to a place where I could celebrate the music and separate it from that. It took Ronnie’s passing for that to happen, ironically. The only regret I have is I got sucked into making the mistake of saying shit about Ronnie because he was saying shit about me. I’m sure that if Ronnie were still alive he’d say he regrets that also. No one benefits from that situation.

Other than that, if I were 23 again, when they fired me, I would do it all again. I stood by my principles, and my principles have not changed. I would do it exactly the same way. I just wouldn’t say shit about Ronnie. I’d just move on.

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.