All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ever since he can remember, Brooks Mason has felt like an old soul in a young body. When he was six, his parents put him in therapy after he insisted that he’d been reincarnated. He showed up at high school parties with a copy of The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions under his arm.

“My friends would be playing Lil Wayne and metal and stuff, and I’d put on Howlin’ Wolf,” he says. “At first, they were like, ‘What the hell are you doing?’ Then they’d listen and they dug it. I told them, ‘You’re listening to the new rap, but Howlin’ Wolf was doing his own kind of rap back in the day. It blew their minds.”

Mason didn’t last long in high school. At 15, he took a decade of guitar playing and studying records by the likes of Freddie King, Albert Collins and Michael Bloomfield, and he set off for the blues clubs of his native Georgia.

My friends would be playing Lil Wayne and metal and stuff, and I’d put on Howlin’ Wolf

Eddie 9V

Leading a six-piece band that included his bassist brother, Lane Kelly, he rechristened himself Eddie 9V – as in the variety of battery – and took his act to every joint that would have him. He went down a smash.

Left My Soul in Memphis, Mason’s 2019 debut album, recorded in a double-wide trailer, signaled the emergence of a vital new blues star. Two years later came Little Black Flies, a veritable blues party that showcased Mason’s skills as an exuberant singer and guitarist, as well as his songwriting partnership with Kelly.

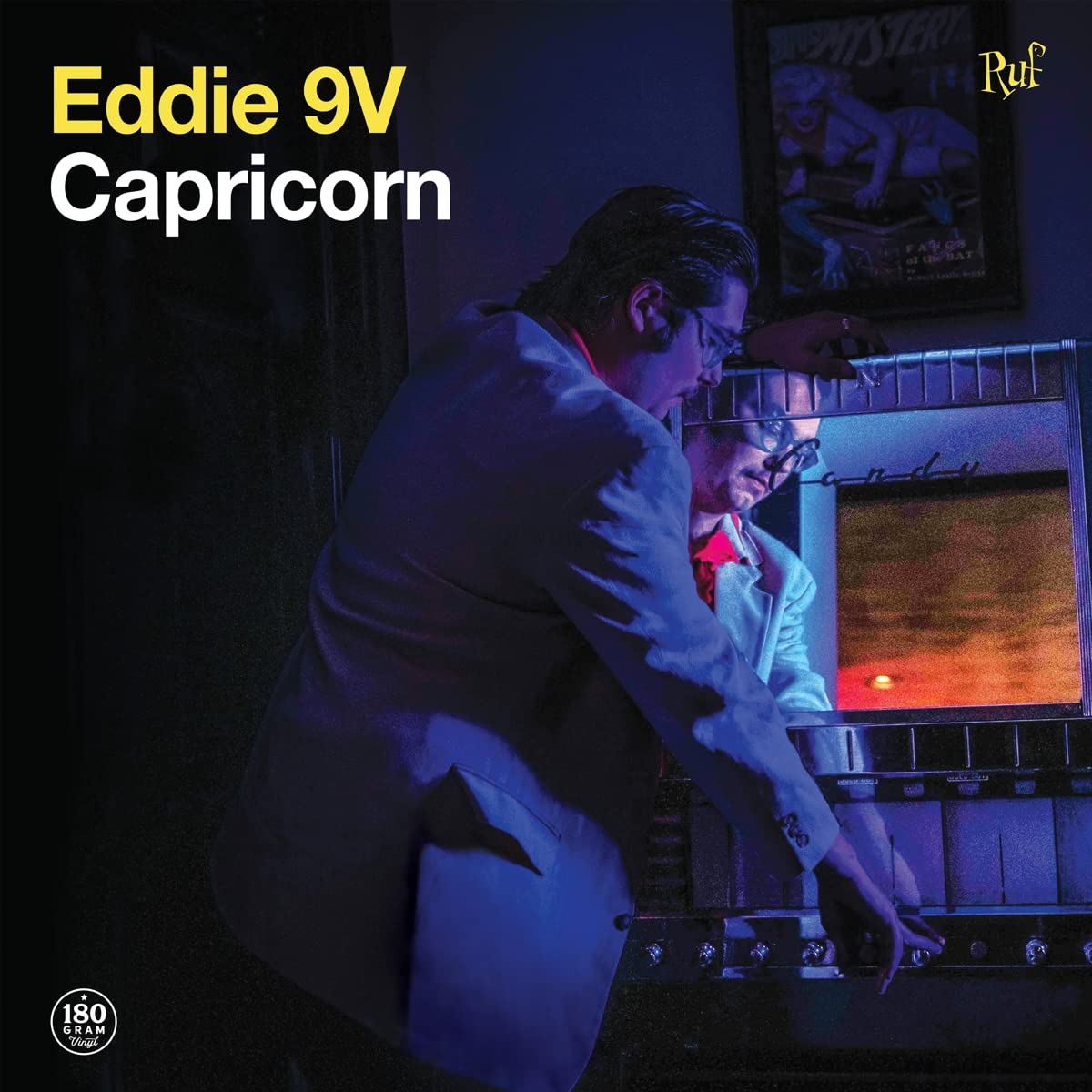

The guitarist’s new album, Capricorn (Ruf Records), recorded at the fabled Capricorn Studios in Macon, Georgia, is something of a breakthrough.

It brims with buoyant Mason/Kelly originals, like the swampy, psychedelic “Yella Alligator,” the gospel-tinged “Are We Through?” and the deep-grooving strutter “Tryin to Get By,” as well as a bruising cover of Bob Dylan’s “Down Along the Cove.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The album is a thrilling evocation of blues and Memphis soul that manages to sound both lovingly vintage and positively modern.

I had a real blast making this album, and I think that comes through

Eddie 9V

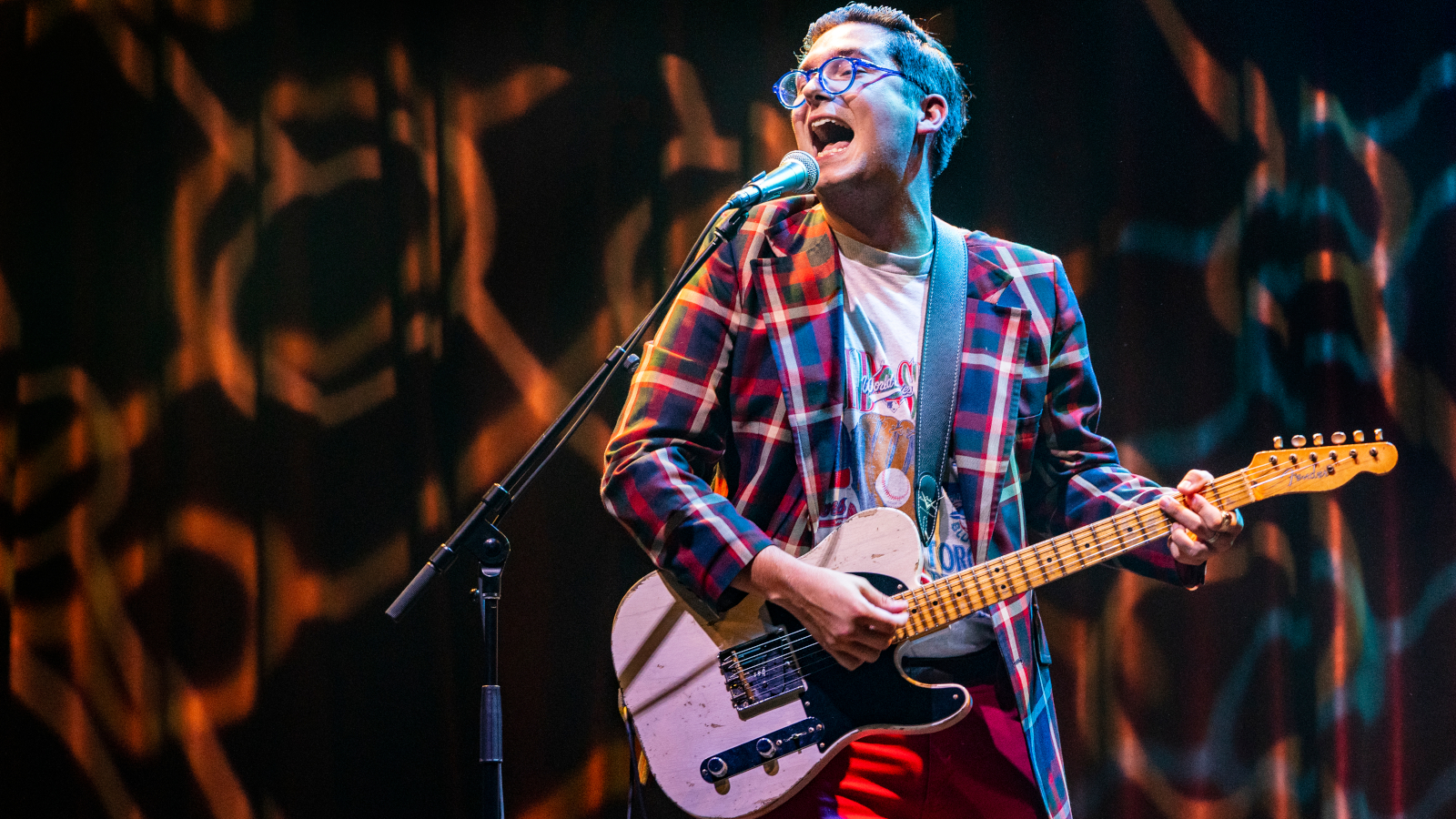

Throughout the good-time set, Mason layers the selections with a guitar approach that balances impulsive, powder-keg power with artful, carefully crafted phrases (he’s joined on a couple of cuts by Macon slide ace Dustin McCook).

He’s also a doozy of a vocalist – grand and charismatic, a real peacock. Give this guy a song, and he’ll put on a show.

“I had a real blast making this album, and I think that comes through,” Mason says. “Of course, recording it at Capricorn Studios was so special to me. The vibes and the history of that place. Walking in, I knew I felt some ghosts.”

He laughs, then adds, “But I’m not afraid of ghosts.”

You left school to play the clubs when you were just 15. So… no plan B?

[laughs] No plan B, man. There’s that classic line: “If you have a plan B, you plan to fail.” I always gave 100 percent to the music I play. My mother didn’t always approve, but now she’s okay with the music thing. My dad always pushed me and my brother. Anytime we felt like giving up, he’d give us a pep talk.

I imagine that playing the clubs had a dramatic impact on your playing ability. You had to get good fast.

Definitely. Nothing gets you sharp like playing in front of people. You have no time to think; you just have to be in the moment and perform. Playing shows in clubs was practice for me. When I’d come home, I wouldn’t even pick up the guitar ’cause I already did my practicing. [laughs] I did my 10,000 hours of guitar practice by the time I was 15.

I entertained people. They dug what I did, so they didn’t feel bad about putting money in the jar

Eddie 9V

Beyond guitar playing, you’re a natural frontman and performer. You really know how to engage listeners.

That came along with my guitar playing. See, for the longest time we made money from passing around the tip jar. We’d play this joint in Atlanta, Fat Matt’s Rib Shack – great place, but they’d only pay the band 100 bucks.

If you wanted to come out of there with real money, you’d work for tips. I felt bad asking for money, so I worked on my stage banter. I entertained people. They dug what I did, so they didn’t feel bad about putting money in the jar.

I can hear bits of influences in your guitar solos – Freddie King, Michael Bloomfield…

Oh, Bloomfield’s my biggie. Everything I learned about building a solo, I got from him. He didn’t just work around the neck; he told you stories. It’s like he started at chapter one and took you till the end.

There’s so many people who influenced me. Derek Trucks, Elmore James.... I mean, we could go on.

From a songwriting standpoint, though, you seem to draw a lot of inspiration from ’60s and ’70s soul.

That’s kind of the transition I’m making. I love the blues, but I don’t want to be just a blues cat. What we’re doing is “Al Green with blues solos.” I’ve played redneck honky-tonks and Manhattan hipster bars, and everywhere I go, they really respond to that kind of music. Soul goes with the blues, and vice versa.

What we’re doing is 'Al Green with blues solos'

Eddie 9V

The song “Yella Alligator” has a swampy blues and soul sound reminiscent of Little Feat. Great slide tone in that song. It’s both caustic and sweet.

You play a Les Paul into a Vibrolux at Capricorn and you’re going to sound good. The slide in the choruses is me, but the slide at the end is played by Dustin McCook. He was like my Duane Allman plug-in. He played on “Down Along the Cove,” the Dylan cover we did.

That’s an interesting song choice, with a Capricorn connection, of course.

There is. Johnny Jenkins covered it at Capricorn. It was 1970, and he had Duane and the Allman Brothers on it. We tried to play ours as close to what they did as possible.

Your soloing and filigrees in “Are We Through?” remind me of Pop Staples.

That’s a huge compliment. The Staples Singers and Pop Staples – big influences, for sure. Pops really knew how to weave his parts around vocals. Man, that song really came together pretty quick. That’s all me on the guitar, and I think I’m on the drums and bass on that one, too.

Mostly I used a Fender Esquire

Eddie 9V

There are some songs that I recorded most of, if not all the instrumentation. But I’d say a good 80 percent of these songs were all done with the band.

What were your main guitars on the record?

Mostly I used a Fender Esquire. It’s a pretty recent Custom Shop model, but they did a hell of a job on it to make it look settled. I also used a Les Paul goldtop that I’ve had for a while. I got it in 2011, I believe, but the thing looks like it’s from 1952 from all the abuse I put it through.

I admit that I beat my guitars up pretty bad. Everybody’s always asking me, “Where are your guitar stands?” I just forget to bring them, so they get knocked around. As long as they keep making music, you know?

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.