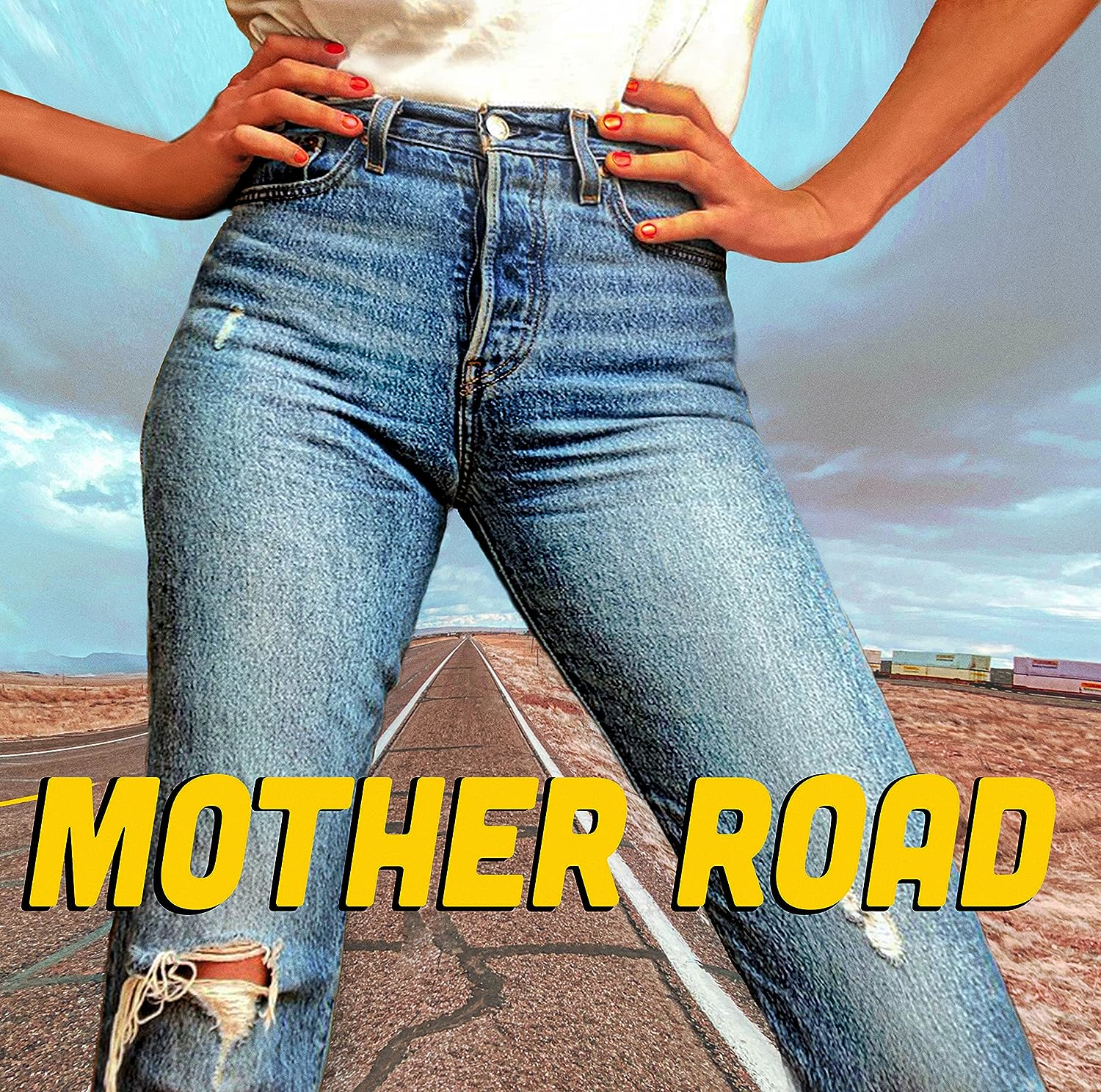

“There’s Nothing Better Than Writing a Cool Riff. But These Songs Were Crying out for Something Different”: Grace Potter Talks Charismatic New Album, ‘Mother Road’

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When asked to sum up the theme of her dynamite new album, Mother Road (Fantasy), Grace Potter answers quickly and definitively: “Belonging,” she says. But as the singer-songwriter and guitarist hunts for words to expand on her explanation, it becomes clear that there’s a lot more to it than a simple one-word response. “Actually, that’s just part of it,” she says. “Along with a sense of belonging, there’s the alienation you can feel once you’ve declared your identity to yourself and the people around you. I wanted to understand my own feelings of alienation that started early on.”

As Potter explains, she grew up legally blind and earned bad grades. She recounts how she was kicked out of school bands because she couldn’t read music. “That all kind of plays with you, and you start to question where you fit in,” she says. “I just started to play music by ear, and I had this revelation that music and musicality were worlds apart.” She pauses. “Ultimately, fitting in became less important to me, and now I don’t even try.”

For a time, Potter had a comfortable place fronting Grace Potter and the Nocturnals, a hard-driving, roots-based quintet that included her then-husband and drummer, Matt Burr. Between 2005 and 2012, the band issued four well-received albums, but it was onstage where the outfit truly shined. A big and brassy singer who knew a thing or two about instrumental showmanship – when she wasn’t laying it down with a Flying V, she was throwing her whole body into a Hammond B3 – Potter was very much the show’s focal point. “I think people got captivated by me, but I was captivated by the band,” she says. “I love playing in a band.”

Her exit from the Nocturnals coincided with the end of her marriage. At first, she felt disillusioned about the nexus between music and her personal life, but now she’s made peace with their inevitable – and it would seem, intractable – connection. “As you get older, it gets easier to let things go,” Potter says. “The Nocturnals were an important part of my life in so many ways. I was discovering what I could do – my voice, my instrumentation. It was the first time I heard the expansive sounds that could make my voice fly. And now I’m going through it again in a really interesting way.”

Since 2015, she’s been making records with her second husband, producer Eric Valentine, known for his work with Slash, Queens of the Stone Age and All-American Rejects, among others. Their first collaboration, Midnight, saw Potter ditch much of her earthy grit for a mainstream pop sheen, and in many ways she sounded like a musical tourist. On 2019’s Daylight, she recalibrated her approach and framed her songs with a more organic, bluesy edge.

Mother Road feels like she’s arrived back home. Much of the album was written during a two-year, back-and-forth road trip across America. On it, Potter is backed by an ace band that includes bassist Tim Deaux, drummer Matt Musty and pedal-steel guitarist Dan Kalisher, along with keyboardist Benmont Tench, from Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, and lead guitarist Nick Bockrath, from Cage the Elephant.

Potter smolders on the swampy country soul of “Ready Set Go” and the funky blues stunner “Rose Colored Rearview.” The spaghetti western–flavored “Lady Vagabond” casts an eerie, cinematic shadow, and tangled blues collides with wild theatricality on “Futureland.” There’s not a musical moment that rings false, and throughout the album Potter, a fluid, emotionally direct storyteller, comes to grips with the vicissitudes of life with unflinching candor.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Potter’s fierce electric guitar playing is less dominant on Mother Road than on previous works. She serves it up judiciously while drizzling dashes of tasty strumming on a nylon-string guitar in various spots. Overall, the emphasis here isn’t so much on riffs as it is on textures and sound treatments. “I was actually surprised at how less indulgent I was with the riffs, because anybody who knows me knows that I love a riff,” she says.

“Believe me, there’s nothing better than writing a cool riff. But these songs were crying out for something different, whether that meant swearing it up or sending it to church. I had to serve the songs and what they wanted, which wasn’t always about power chords and specific lines.” She chuckles. “I was looking for the charisma of the guitar.”

As you get older, do you find that you have to find ways to renew your relationship with the guitar?

Totally. In fact, I was just having this conversation with one of the new guitarists in my band, Charlie Shea. He showed me a video of a little girl rocking out on a nylon-string guitar. She was playing this fantastic stuff, and the words she sang were so silly and rude – the kinds of things little kids sing when they make up songs. I loved it. I think having a kid has helped me to understand just how irreverent music allows us to be.

Also, it’s important to realize that guitars are just toys. That’s it – they’re complicated toys. Having just picked up a nylon-string guitar myself for this tour, I’ve really come to appreciate what a fantastic toy it is. I think a lot of guitarists lose sight of that. We get to play these brilliant toys and make music with them.

You’ve played around with a lot of genres over the years. Has that opened you up to any new guitar influences?

Oh yeah. All day, every day. The name Jack Nitzsche came up a lot during the making of this record. [Nitzsche was a producer, songwriter and musician whose work spanned from Phil Spector and the Rolling Stones to films.] That guy was a fucking badass. Also, the acoustic guitar playing on those early Bobbie Gentry records – she seemed to write all of her songs with these acoustic intros. They were simple yet hooky, and they drew you in. That kind of thing made it onto my record.

Its important to realize that guitars are just toys. That’s it – they’re complicated toys

Grace Potter

I was also listening to a lot of mariachi music, and that brought me down a rabbit hole of spaghetti-western composers. Ennio Morricone was the obvious one, but there were others. I got into all the musicians and guitar players on those scores.

You mention Morricone. “Lady Vagabond” has those eerie, twangy guitar lines running through it.

Precisely. I was absolutely going for that. Also, on that track, I’m playing Dave Cobb’s beautiful 1948 Martin nylon-string guitar.

Let’s get into that. How has playing a nylon-string guitar affected your technique?

A lot. The nylon-string is a completely different animal – and a humbling animal. I’m very absurd when it comes to introducing something new; I need to recognize the theatrics behind it. First and foremost, that guitar of Dave’s has a heart and soul. I started the song “Lady Vagabond” after touching that guitar. The guitar brought it out of me. It’s such a buttery-sounding instrument.

It sounds like you want to do more of this in the future. Do you want to study fingerstyle guitar?

Yes! I want to go down to Brazil and get me a Brazilian lover who will teach me some bossa shit. That’s my new thing. [laughs] My husband knows this, and he’ll be there with me. I’m devoted to learning, and I’ve been humbled by every instrument I’ve picked up. No instrument is easy. If you want it to sound good, you can make it sound good one time in a studio. If you’re going to bring it out into the world and try to look like you know what the hell you’re doing, you gotta put your money where your mouth is. I’d love to get more into fingerstyle and flamenco style, and I think it could inform my next record.

Looks like you’ll be buying more nylon-string guitars.

Actually, I have three – they’re all off-brand. My husband has a beautiful ’60s Martin that only has five strings. But nothing comes close to Dave Cobb’s guitar, and trust me, we tried. I asked him, “What would it take for you to part with this guitar?” He said, “That won’t happen. Not a chance.” Understandably.

You remain a very strong rhythm player. Where did that come from?

It all started with Led Zeppelin and Gillian Welch. I thought that if I could do those two things, that would be great. I love Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings’ records, and I was born with Led Zeppelin in my blood. But when I started understanding that it all comes from the blues, it all made sense to me.

Also, I realized I could put together a rhythm bed on the guitar for me to sing over. It’s come pretty naturally to me. I love writing riffs and lead guitar parts, but those elements are like film scoring. Rhythm playing is more physical.

You play some wonderful rhythm guitar parts on the record on songs like “Rose Colored Rearview” and “Ready Set Go.” On “Good Time,” you get into a swampy rhythm that reminds me of Little Feat.

[laughs] Man, that’s cool! I never thought of that. I was thinking Dr. John, Billy Preston and the Meters. But Little Feat? That’s cool. I’ll take that.

I thought we were just going in to make demos in Nashville...But we got 14 songs cut in seven days

Grace Potter

Did you play the solo on that song? The tone and phrasing remind me of Keith Richards on “Sympathy for the Devil.”

Whoa, also cool! No, I didn’t play that. I tried it out at the beginning, but then I met Nick Bockrath, from Cage the Elephant, and that was the end of that. I was writing the guitar parts, as I always do, but once Nick came in I stopped worrying about what was going to happen melodically. He brought so many new ideas into the record, and that’s exactly what I wanted.

I echo-chambered these songs enough, so I was ready to bring other people into my weird universe. Nick played a few solos, and I really loved how he could go in a lot of directions. I had written some parts to “Mother Road,” but I was kind of bored with them. Then I heard Nick sort of riffing around, and I said to the band, “Everybody listen to what Nick is doing. I want you to redo your parts.”

Did you road test any of the new songs before recording?

Not a one. I thought we were just going in to make demos in Nashville. It was all brainchild stuff that was supposed to be the beginning of a year-long series of recording sessions. But we got 14 songs cut in seven days, so that was that.

Is it a little scary doing it that way? When you test songs out live, you can tell which ones work. This way, you have no idea.

That’s true, but I didn’t care. Making this record, I wanted to see if music was still what I wanted to do. I went through a process of trying to understand myself as a mom as well as my role in the world. That all goes with the sense of belonging I mentioned before. I needed to not care. The songs just fell out of me. It was a great experience. I laughed it up with everybody in the studio, and that was the vibe. Somewhere in there, music got made, and I could tell it was good.

Aside from Dave Cobb’s Martin, what other guitars did you use on the record? I assume you pulled out your Flying V.

I sure did. The Flying V is still going strong. That’s where I’m most comfortable. The nylon-string is a new sport to me, and it is a sport – an Olympic sport. I’ll play the nylon-string live on some songs. We debuted “Lady Vagabond” at a raucous show the other night, and I didn’t get booed for my attempts at nylon. I’ll be playing my Flying V and my J-45.

We also have two new guitarists who’ve come aboard – Indya Bratton and Charlie Shea. They’re both badasses and they cover all the sounds and styles that my music needs. With them playing in the band, it matches the Nocturnals’ sound, because I’ve got that dueling guitar thing going on.

How many Flying Vs do you have?

On the road, I have three, but I’m embarrassed to say how many I have at home. [laughs]

I want to be remembered as somebody who made the guitar world a little bit better. I think my gritty elegance speaks to my irreverence

Grace Potter

Oh, come on. Do you know the number?

Right now, there’s 12. It’s mainly because Gibson isn’t making my signature model anymore. I like to keep some around just in case I get those random phone calls from Lenny Kravitz when he’s looking for a Flying V. I sent one to Gary Clark Jr.

Wait a second. These are big-name players with their own connections to guitar companies. What are they doing calling you for instruments?

Oh, I think it’s great! In my life, I want to be remembered as somebody who made the guitar world a little bit better. I think my gritty elegance speaks to my irreverence, and the Flying V is one of the most irreverent instruments around.

Has playing the Flying V caused any particular quirks in your approach? You do have to position it differently against your body.

Oh, hell yeah. I one-hundred percent play differently. I specifically chose that guitar because it swings like a pendulum, and it kept me from overextending myself. If I played a Les Paul or a Telecaster, I would get more of an AC/DC feeling – I’d just jump off the stage. The first time I was onstage with a Flying V, I felt grounded. Plus, there’s the way it sits on your body, and I’ve got a woman’s hips, you know? [laughs]

The V centers me and keeps my feet on the ground. I still like to flail, don’t get me wrong, but I can’t climb on many things with a V strapped around me. Its ergonomics are different from other guitars. The Flying V is its own thing.

Visit the Grace Potter website for tour info, merch and more.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.