Summon the Power of the Metal Gods and Add Some of Michael Schenker’s Magic to Your Own Playing in This in-Depth Lesson

A tribute to the Flying V-wielding MSG, Scorpions and UFO guitarist’s elegantly melodic metal riffing

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Equipped with his trademark black-and-white Dean Flying V, Michael Schenker has spent the last half century wending his way through a rich musical life, including his early days with the German metal band Scorpions (as co-guitarist with brother Rudolph Schenker), a number of stints with UFO and a multitude of incarnations of his Michael Schenker Group (MSG).

What has remained constant over the years is the guitarist’s unique, high-voltage mix of rock, metal, blues and neoclassical styles, a penchant for writing snarling riffs, and his singular ability to make his guitar scream and cry with his killer tone and ferocious technique.

In this lesson, we’ll be exploring how to add some of Schenker’s magic to your own playing. Having released virtually an album a year since 1980, Schenker has a host of material to draw from, but we’ll hone in on some of his most celebrated works.

Aside from his ornate sense of melody, which will be the focus of much of this lesson, Schenker’s legendary high-octane tone is what strikes the listener first. The foundation of his concise rig is the Flying V and two Marshall JCM 50-watt amps paired with Marshall cabinets loaded with Celestion Greenback speakers.

While he sparingly employs two Boss effects pedals – a CE-5 Chorus Ensemble and a DD-3 Digital Delay – it’s his artful use of his Dunlop Dimebag wah that is most striking. Instead of using the pedal conventionally – rocking it back and forth, freely or in rhythm – the guitarist most often “parks” his in a stationary position, roughly halfway through its rotation, to act as an EQ filter. This creates a pronounced, narrow midrange “bump” in the frequency spectrum – what Schenker and others refer to as the “sweet spot” – defined by an infectious dark warmth that’s equally at home in the heaviest songs and the most delicate ballads. The result is a key element of one of his signature lead tones.

My first encounter with Schenker’s metal mastery was MSG’s 1982 release Assault Attack, the only album featuring vocalist Graham Bonnet, who also famously lasted for only one show. (He was summarily fired for various onstage antics, including exposing himself, which he has indicated was accidental.) The songs are epic, and Schenker’s lead work is captivating, darting back and forth between searing intensity and soulful beauty, often within the same song. One such classic is “Desert Song,” which we’ll examine in depth, as it showcases more than a few hallmarks of the guitarist’s captivating style.

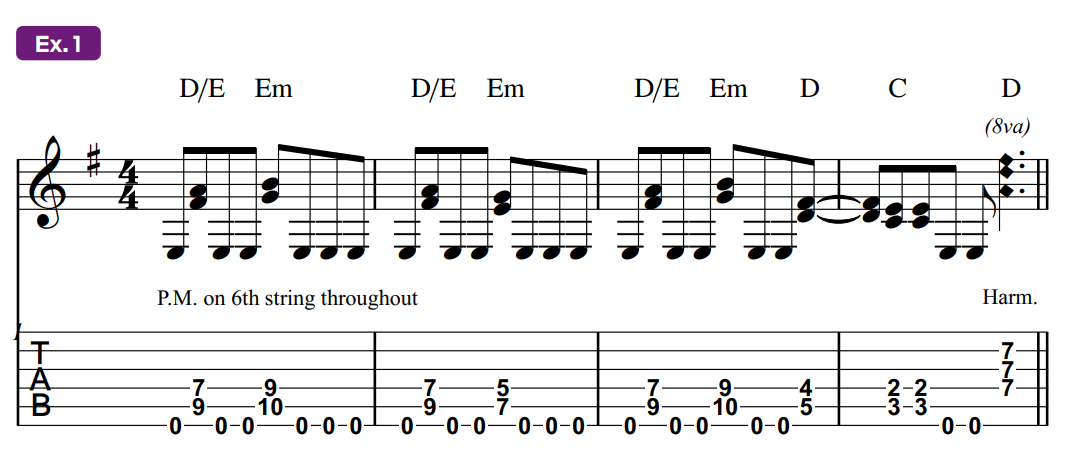

The song’s haunting main riff weaves a palm-muted open low E-string pedal tone through a melody based on the E Aeolian mode, or natural minor scale (E, F#, G, A, B, C, D) and harmonized in diatonic (scale-based) 3rds. Ex. 1 is informed by this same approach. When strumming each dyad (two-note chord), be sure to release the palm mute from the previous open low E note quickly enough so that the fretted notes aren’t muted and ring clearly.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

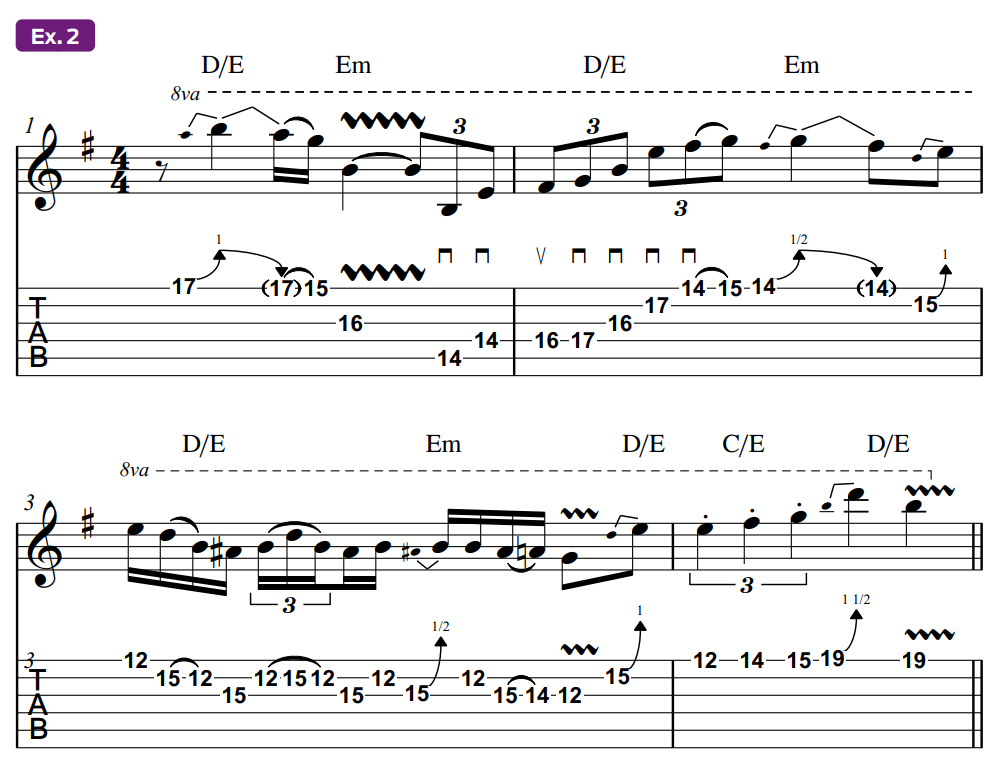

Inspired by Schenker’s soloing in the same song, Ex. 2 demonstrates how he seamlessly weaves together elements from different musical styles. We’re in the same key of E natural minor, and what begins as a standard rock lick dovetails effortlessly into an ascending neoclassical-flavored line built from an Em arpeggio (E, G, B). This leads into the phrase in bar 3, which is based on the E blues scale (E, G, A, Bb, B, D). (Note that in this example the b5, Bb, is notated as its enharmonic equivalent, A#, which is the #4.)

Next up, in bar 4, is an ascending series of staccato notes (played short, as indicated by the small dots above the note heads), which are derived straight from the E natural minor scale. The phrase wraps with a big, one-and-one-half-step bend, a move influenced by players like B.B. King.

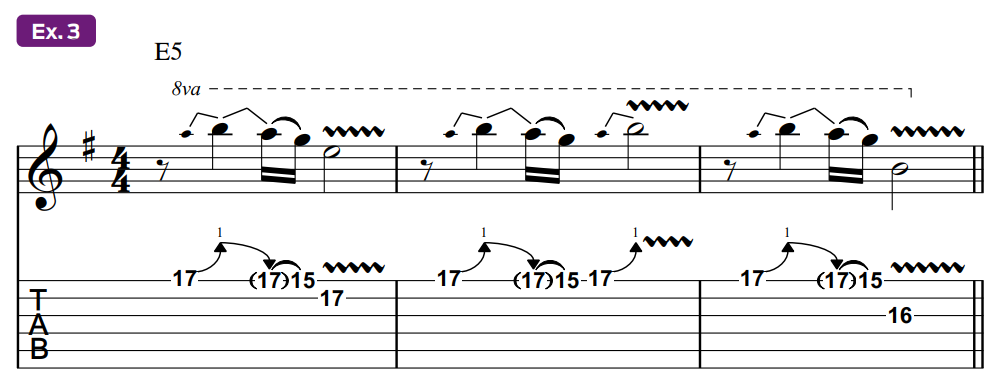

Before continuing, I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out the very Schenkerian twist in Ex. 2’s opening phrase. After the initial bend, many other players would summarily end the lick on the root note E, as in bar 1 of Ex. 3. Others might end by going up to the 5th (B), as in bar 2. Schenker, however, would often resolve high bends to the lower-octave 5th (bar 3), creating a wide intervallic jump, which is a nice surprise for the listener, and also just darn tasty. (Notice, too, the use of a wide finger vibrato here, which is another hallmark of Schenker’s lead playing and touch.)

This kind of melodic adjustment may seem like a small thing, but it opens up new soloing possibilities, as it enables you to subtly but effectively alter licks you already know, with no heavy lifting. Simply displace one note down or up an octave.

At the 2:38 mark, “Desert Song” enters a quieter moment, a beautiful interlude that showcases Schenker’s keen melodic sense. As the section continues, his main guitar is supported by a choir of overdubbed harmony lead guitars. For more information on how to approach that, see my tribute to Boston’s Tom Scholz. For this lesson, though, I’d like to instead go behind the scenes and explore some underlying concepts that can help you compose effective guitar melodies of your own. Keep in mind, Schenker’s deft touch can’t be discounted as a major factor in why his guitar sings the way it does. But that’s a lesson for another day.

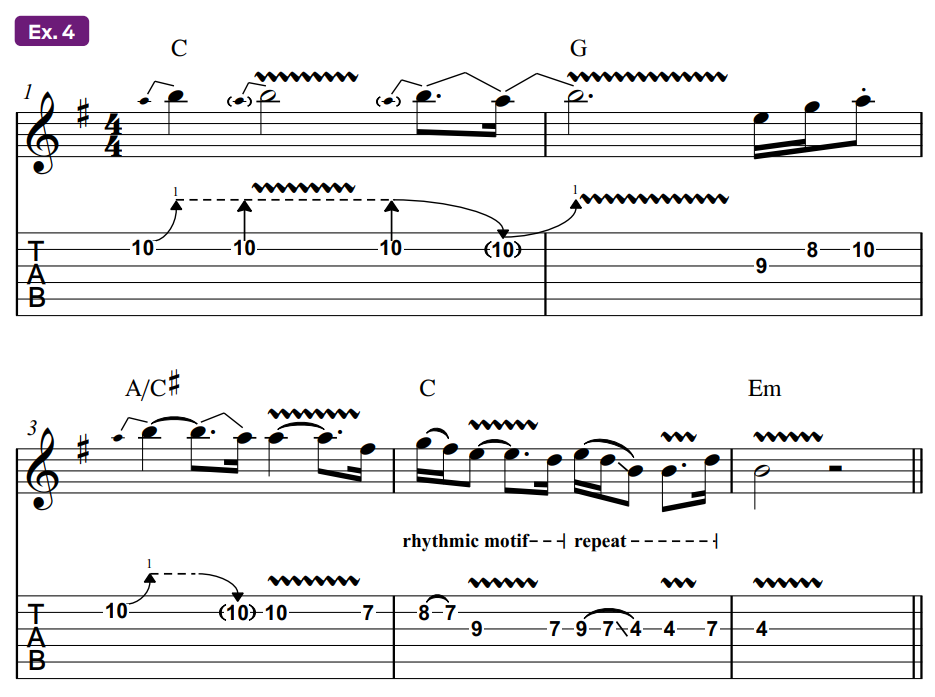

Ex. 4 is based on the “Desert Song” interlude and opens with a series of bent notes, creating a melody with minimal fret changes. Why is this so compelling? Mainly because the underlying chord progression provides movement of its own, with each chord change altering the harmonic context, or “flavor,” of the mostly static melody notes. Sometimes you can simply let the chord changes do the work, and instead play a melody on top that complements this movement by offering some contrast, in the form of staying on the same note(s). (Quick tip: These elements work just as well for composing vocal melodies, or for any melodic instrument.)

Let’s take a closer look at our example. Over the opening C chord, the main melody note, B, functions as the major 7th of the chord (C, E, G, B), while over the G chord, it functions as the major 3rd (G, B, D). Each of these functions brings its own character, or color, which changes along with the chords, even though the note itself pretty much stays the same. You can often find a single note that will sound great over a whole series of chords. For a fun example, check out Brazilian composer Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “One Note Samba.”

Even though we’ve just analyzed the first part of our melody – and this can indeed prove fruitful at times – I’m going to take a bit of a U-turn now and recommend that you don’t do too much of this sort of thing. Instead, the key is to simply trust your ears. A note’s relationship to a chord may not always make musical sense, but it might very well sound good, and that’s what counts.

Another element of composing appealing melodies is the use of motifs, which are short melodic or rhythmic ideas that can be repeated and developed, via slight alterations. In bar 4 of Ex. 4, the first two beats present a rhythmic pattern, which is then recalled with different notes through beats 3 and 4. Notice also how the phrasing is slightly different: Instead of tying the third note of the motif to the following beat, as happens with beats 1 and 2, the third note is rearticulated, here on the downbeat of beat 4.

Schenker was an early proponent of neoclassicism in rock guitar, though he gravitated toward incorporating more lyrical classical-style melodies into his music

The lesson here is to always strive to be open-minded and creative, as opposed to rule-bound, so as to avoid composing cookie-cutter melodies. Incorporating and developing motifs in your own licks and melodies can help to make them more cohesive, engaging and memorable.

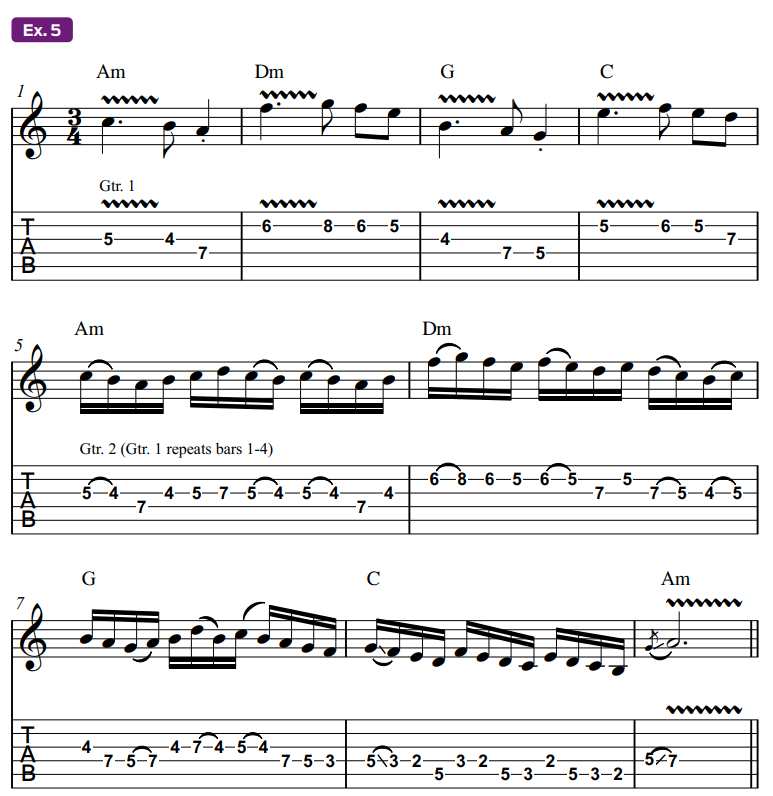

Schenker was an early proponent of neoclassicism in rock guitar, and though he could shred with the best of them, he gravitated toward incorporating more lyrical classical-style melodies into his music. The instrumental track “Bijou Pleasurette,” from the Michael Schenker Group’s eponymously titled 1980 debut album, is a prime example of how the guitarist would don his arranger’s cap to layer melodies. Ex. 5 is based on this lovely piece and begins with a simple four-bar melody built from quarter notes and eighth notes.

Much as in opera, where two or more vocalists will simultaneously sing different melodies without creating a confusing mess, Schenker does a similar thing in this piece, adding a second melody, this time based on 16th notes, which informs bars 5-8 here. Varying the rhythm in this way allows each line, or “voice,” to come across clearly, despite the presence of overlapping notes. Layering melodies like this takes listeners through a melodic maze, with two or more lines simultaneously emerging together on the other side.

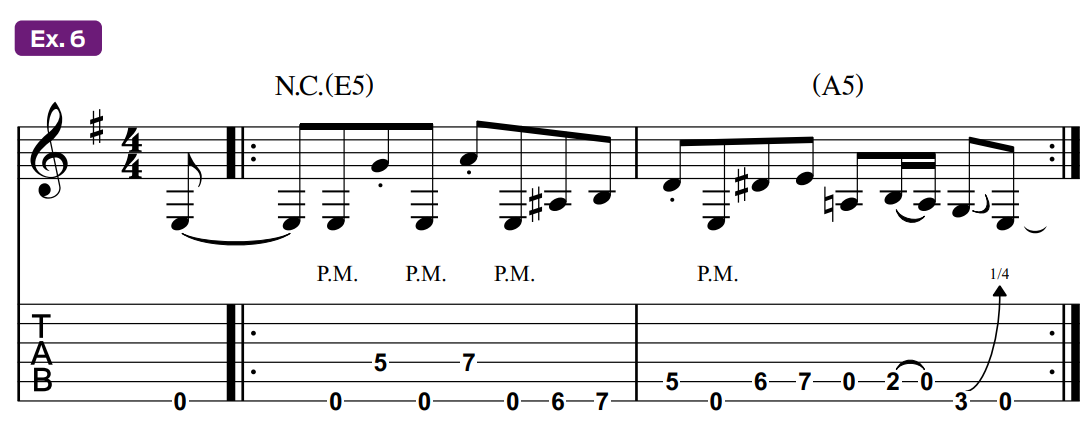

Schenker’s savvy at combining a sense of classical melody with raw blues-rock power found him crafting heavy riffs like the one that opens the classic UFO song “Rock Bottom,” from the 1974 album Phenomenon. It was the band’s third record but the first to feature Schenker, who had recently parted ways with Scorpions. Inspired by this barnburner, Ex. 6 is drawn almost exclusively from the E blues scale. However, Schenker nods to his classical side by including the note D#, the raised 7th degree, borrowed from the E harmonic minor scale (E, F#, G, A, B, C, D#). It’s a subtle and very cool twist.

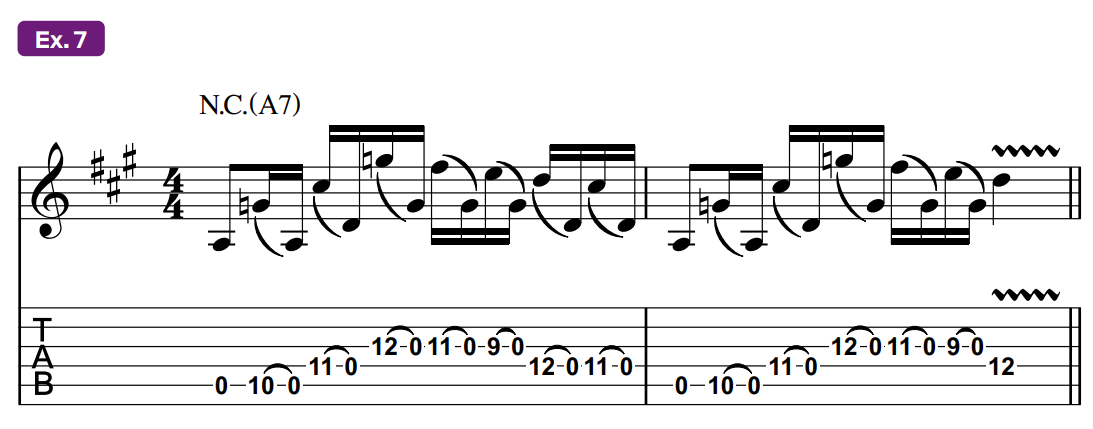

Sometimes Schenker just flat-out has fun crafting playful-sounding riffs, and “Captain Nemo,” from MSG’s 1983 release, Built to Destroy, is a prime example of this aspect of his musicality. Ex. 7 brings the song’s main riff to mind, as it similarly features notes fretted high up on the neck being pulled off to open strings. Doing this produces wide, angular-sounding intervals that make it sound as if the notes are bouncing across the room.

After picking each fretted note, lightly rest the heel of your pick hand on the strings, just in front of the bridge, in order to dampen the open notes and prevent them from ringing too much. Even though this is a bit of an odd riff, it’s also infectiously melodic, yet another Schenker trademark.

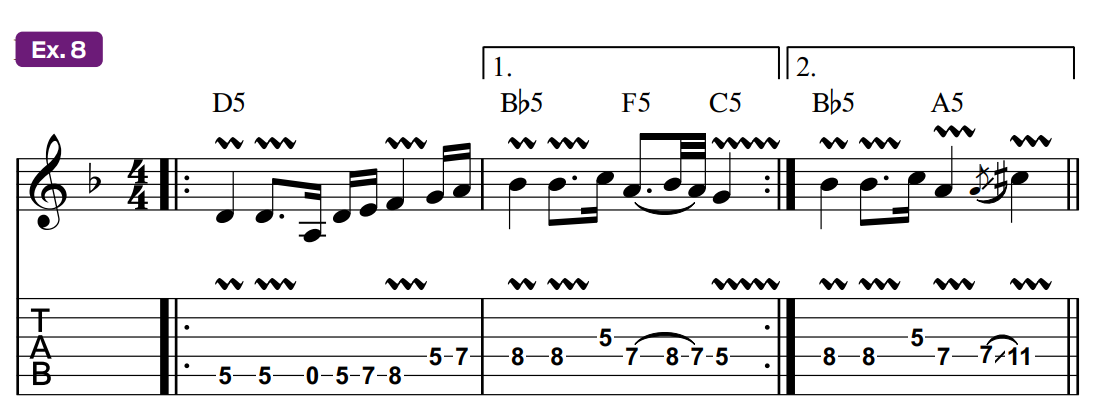

In 1995, the guitarist reunited with UFO to release Walk on Water. By this time, Schenker’s writing and playing had evolved, while it retained the core elements that made his work during the ‘80s so compelling. His guitar melodies now often leaned less on being overtly classical, in favor of a more modern rock edge, but his direct approach and tunefulness still guided his composing. A great example of Schenker’s mindset during this period is the majestic melody he plays behind the vocal during the chorus of “Darker Days.” Ex. 8 is inspired by his playing on this track. Notice how the initial rhythmic motif, with the dotted eighth note followed by a 16th note, is developed in bars 2 and 3.

As he moved through the 1990s and beyond, Schenker continued his torrid pace of writing and performing, all while playing with the same fire and gusto he had when he first burst onto the scene with Scorpions in 1972. Fifty years later, in 2022, the guitarist embarked on a world tour to celebrate all that he has accomplished so far in his career. You can still catch him gracing the stage, with the points of his Flying V astride one leg and his guitar aimed towards the sky, as if to summon the power of the metal gods.

Jeff Jacobson is a guitarist, songwriter and veteran music transcriber, with hundreds of published credits. For information on virtual guitar and songwriting lessons or custom transcriptions, reach out to Jeff on Twitter @jeffjacobsonmusic or visit jeffjacobson.net.