Get Inside the Mind of Jimi Hendrix

Put Jimi Hendrix’s chord inversions, melodic scale-tone embellishments and jazz voicings to work in your own rhythm-guitar playing with this insightful lesson.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

*** The accompanying audio for this lesson can be found here ***

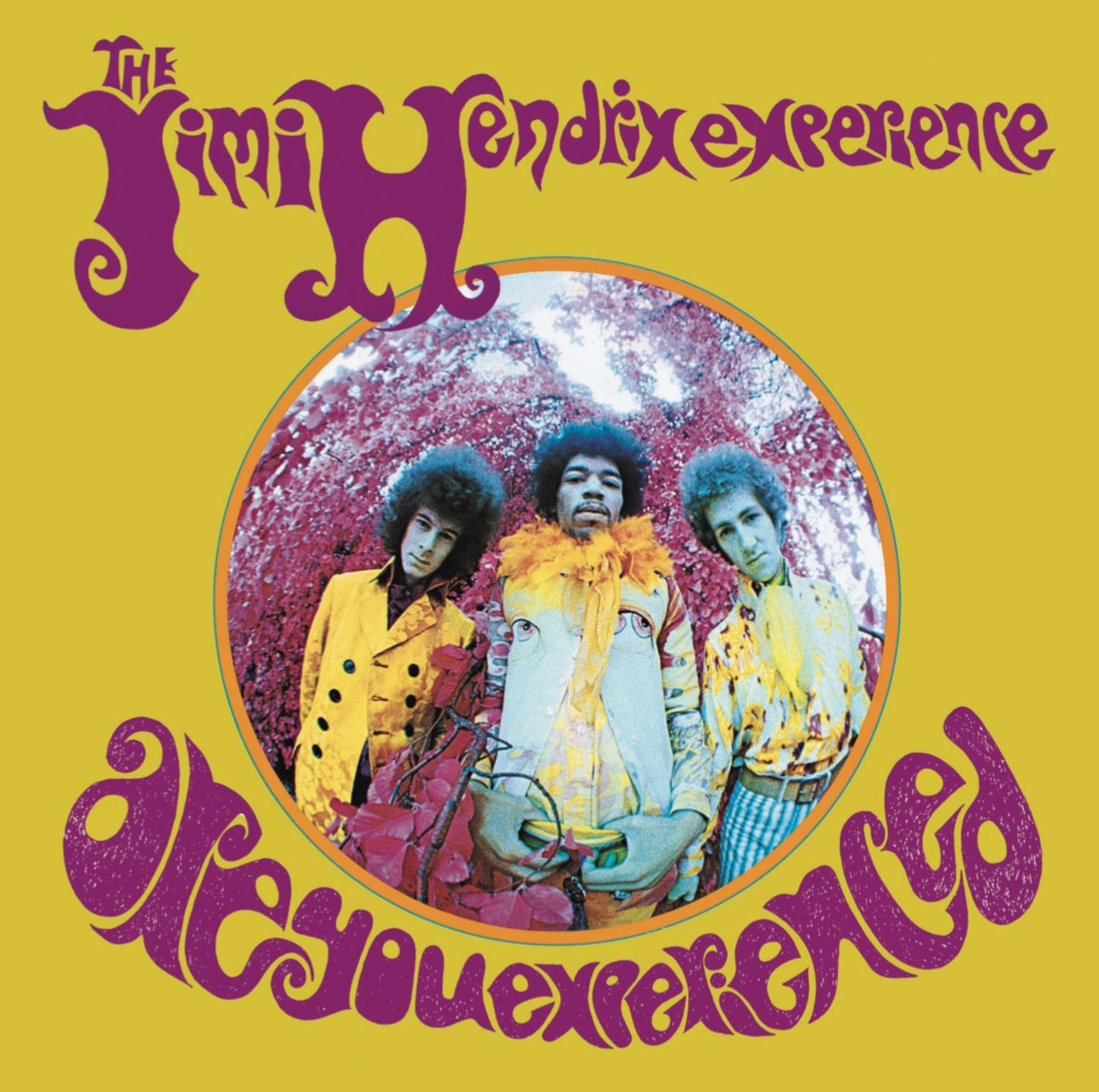

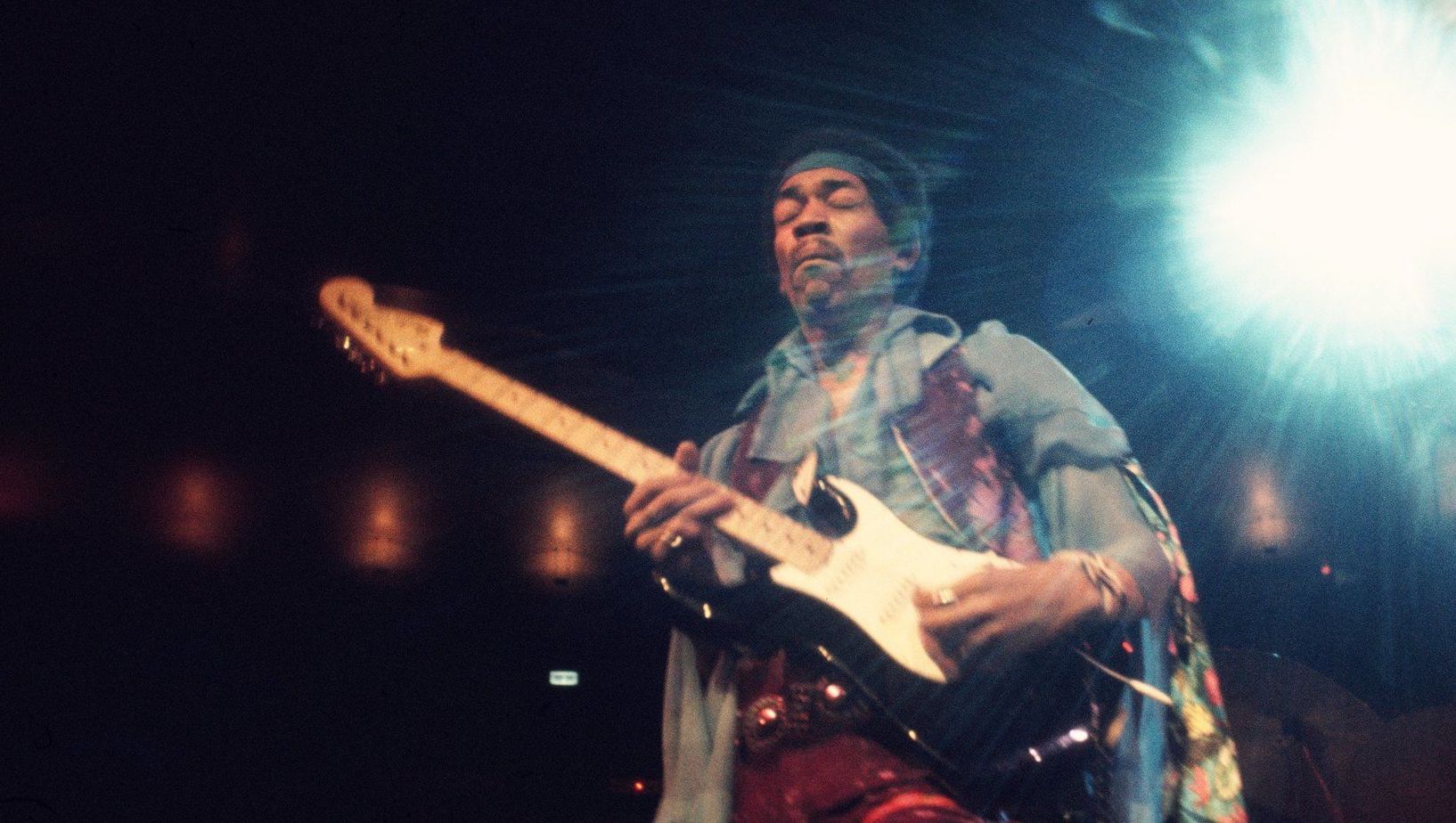

No guitarist has influenced music and culture as profoundly as Jimi Hendrix did. Even before burning and smashing his Fender Stratocaster during the bombastic finale of his 1967 Monterey Pop Festival performance, the visionary musician had revolutionized the world of electric guitar with his unique approaches to playing the instrument and using it with his amplifier and effects to create new, otherworldly sounds.

While Jimi’s innovative lead guitar style has been widely analyzed and imitated by countless players in the decades since his passing in 1970, one aspect of his six-string artistry that is equally groundbreaking and often overlooked is his approach to playing chords and rhythm guitar.

This is where he stands far above his many imitators. As Hendrix famously demonstrated in his ballads, he would often ditch standard barre chords in favor of melodic phrasing built around and woven into chord inversions.

In this lesson, we’ll explore this and other aspects of Jimi’s rhythm guitar style and technique with original examples inspired by such signature songs as “The Wind Cries Mary,” “Castles Made of Sand” and “Little Wing.”

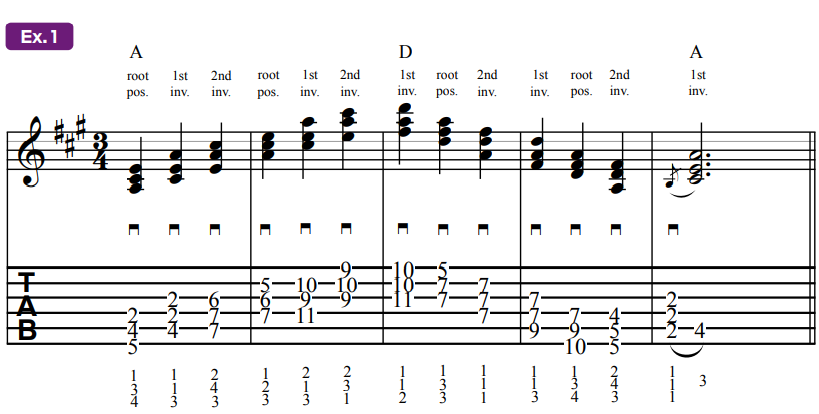

Inversions

In music theory, a voicing refers to the vertical arrangement, or “stacking,” of notes in a chord. For example, an A major chord is made up of three notes, A, C# and E, which are the root (1), major 3rd and 5th, respectively.

If you play these three notes together in ascending order, from low to high, the chord is said to be in root position, for which the root is the lowest note, being on the bottom of the voicing, or “in the bass,” as they say.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

If you take the A note and move it up an octave, it then becomes the top note of the voicing, rendering the ascending order of notes C# , E, A. The chord is now in what’s called 1st inversion, for which the 3rd, C# , is in the bass, Likewise, flipping the C# note up an octave leaves the 5th, E, on the bottom of the note stack, giving us what’s called a 2nd-inversion voicing, for which the 5th is in the bass.

Ex. 1 has you playing these A major chord voicings in ascending order through two octaves, running up the neck in the first two bars. Then, in bars 3 and 4, you will descend a series of D major (D, F#, A) inversions before finally ending back on A.

The shapes used here are all common major chord inversions and close-position “grips,” and they’re all essential building blocks for understanding Hendrix’s approach to rhythm guitar playing that should be learned well in a variety of keys.

Now let’s look at how Jimi would creatively make use of these kinds of shapes.

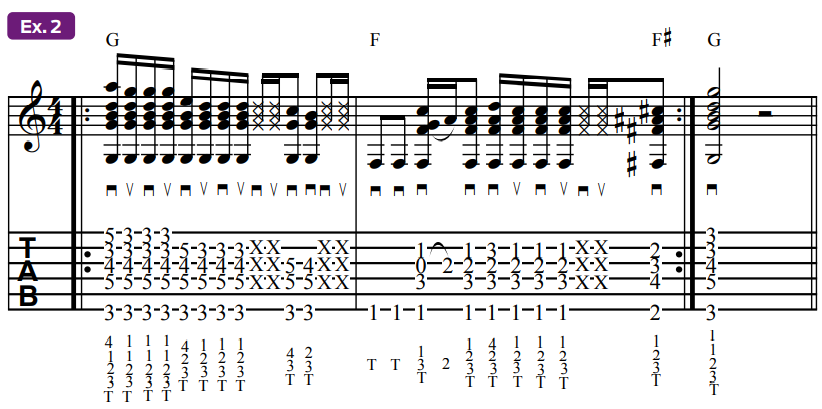

Breaking the Barre

This unorthodox fretting approach gave the guitarist the option to utilize his now-freed-up 4th finger (the pinkie) to add decorative melodic embellishments and momentary “extensions” to the chord. This technique is showcased most famously in early hits like “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cries Mary” (both from Are You Experienced).

One of Hendrix’s greatest contributions to the rock guitar vocabulary stemmed from his eschewal of standard six-string barre chord shapes, for which the index finger (1) serves as a movable capo clamped across the strings.

Instead of using these stock chord forms, which are technically restrictive, as they use up all four fingers, the guitarist opted to instead hook his thumb around the top side of the fretboard and use it to fret the root of the chord on the low E string while fingering a root-position triad on the D, G and B strings with his 3rd, 2nd and 1st fingers, with the 1st finger sometimes forming a mini barre across the top two strings, to double the root note an octave higher.

When utilizing thumb fretting this way, it’s very important that the tip of the thumb extends beyond the low E string to lightly touch and mute the unused A string, so that it does not ring open when you strum across the strings, just like when you play a strummed octave on non-adjacent strings, which is what happens here within the chord voicing.

Jimi had large hands, which made this technique seemingly effortless for him to employ. Having a fairly thin neck profile on your guitar makes the technique easier to perform than on one with a chunky “baseball bat”-like neck.

If you’re having difficulty with the technique, try performing it on a guitar with a thinner neck. Another helpful option is to additionally mute the unused A string with the tip of your 3rd finger as your fret the D string.

Ex. 2 revolves around a two-chord progression (G to F) and demonstrates how you can use the available surrounding major-scale tones related to each chord to achieve the kind of “chord-melody” activity that’s a hallmark of Hendrix’s distinctive rhythm guitar style.

Start by fretting a root-position G major triad (G, B, D) with the root note doubled an octave higher on the high E string (via a 1st-finger mini-barre), then add your thumb on the low E string to thicken and bolster the voicing, by doubling the root note an octave lower.

With this G chord as your base, you will in turn add the “extensions” A, E and C – all of which are conveniently located at the 5th fret on the top three strings – to the chord, fretting each of them with your 4th finger.

In bar 2, you will shift down two frets and one whole step to an F chord (F#, A, C) and utilize the open G string in addition to fretted scale tones similarly patterned after those in the previous bar. Since we’re not utilizing the high E string here, you needn’t form a mini barre across the top two strings and can fret the B string with the tip of the 1st finger.

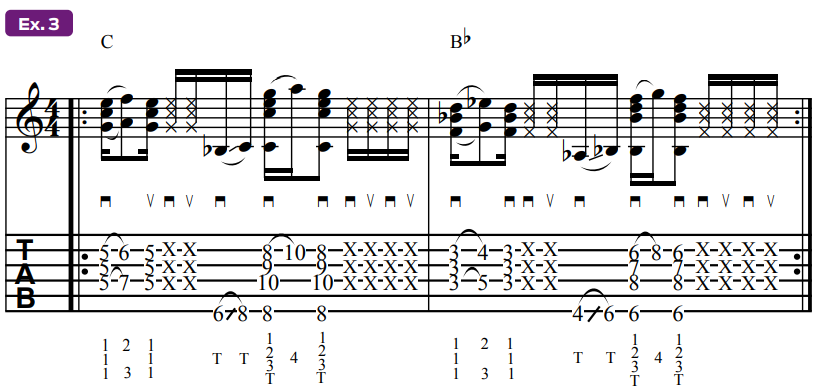

Ex. 3 is inspired by the opening riff to “Wait Until Tomorrow” (Axis: Bold as Love). Begin in 5th position, playing a C major triad in 2nd inversion (voiced G, C, E, low to high) with your 1st finger barring the D, G and B strings. Then hammer-on to an F major triad (F, A, C) in 1st inversion with your 2nd and 3rd fingers before resolving back to C.

As the overall harmony doesn’t change when you hammer-on to the F triad, this produces the effect of suspension and resolution. Suspension is the musical tension created by replacing a chord tone, such as a major or minor 3rd, with a non-chord tone – most commonly substituting the 4th or 2nd (sus4 or sus2) for the 3rd – followed by the return and resolution to the chord tone.

From there, use your thumb to fret the sliding root note on the low E string, ultimately landing at the 8th fret, where you will fret a root-position C major triad, with an added 4th-finger B-string hammer-on for melodic interest, moving from the 5th of the chord, G, to the major 6th, A, and back.

In bar 2 you shift down to 3rd position and mimic the previous sequence from bar 1 a whole step lower, centering everything around an embellished Bb major chord (Bb, D, F).

Pulling Out All the Stops

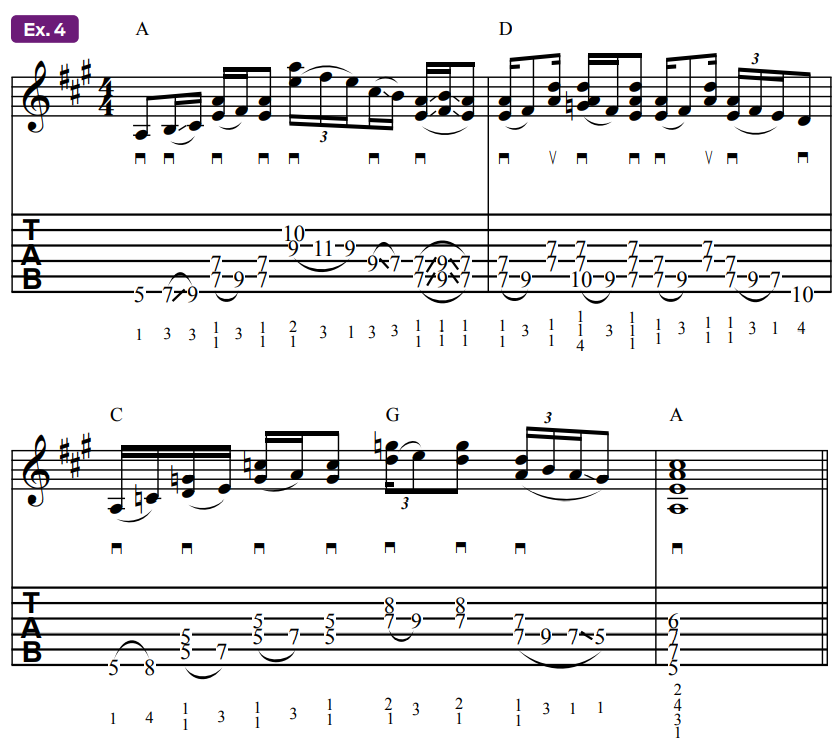

Just as often as he would play inversions in the straightforward manner detailed earlier, Hendrix would break apart inversions by playing double-stops and single-note melodies around them.

Ex. 4 demonstrates this approach applied to a simple four-chord progression: A - D - C - G. You begin by framing an A major chord, sliding into a 1st inversion voicing, only here instead of playing the full three-note triad, you will play the bottom note C#, then subsequently perform a double-stop with the remaining tones (E and A) above, hammering-on to the 9th fret on the A string for added melodic tension before resolving to the original chord.

You’ll continue playing the progression in this manner, with legato finger slides and double-stop hammer-ons and pull-offs liberally employed throughout, Hendrix style.

Note the use of triple-stops in bar 2, which incorporate suspensions – sus4 and sus2 – based around the 1st-inversion D major chord, which is a move Hendrix often used to brilliant effect.

The common thread throughout this example is the way each chord, rather than adhering to one single overall scale, is “borrowing” neighboring tones from its own related major pentatonic scale. This concept is a hallmark of Hendrix’s singular approach to key and tonality. More on that later.

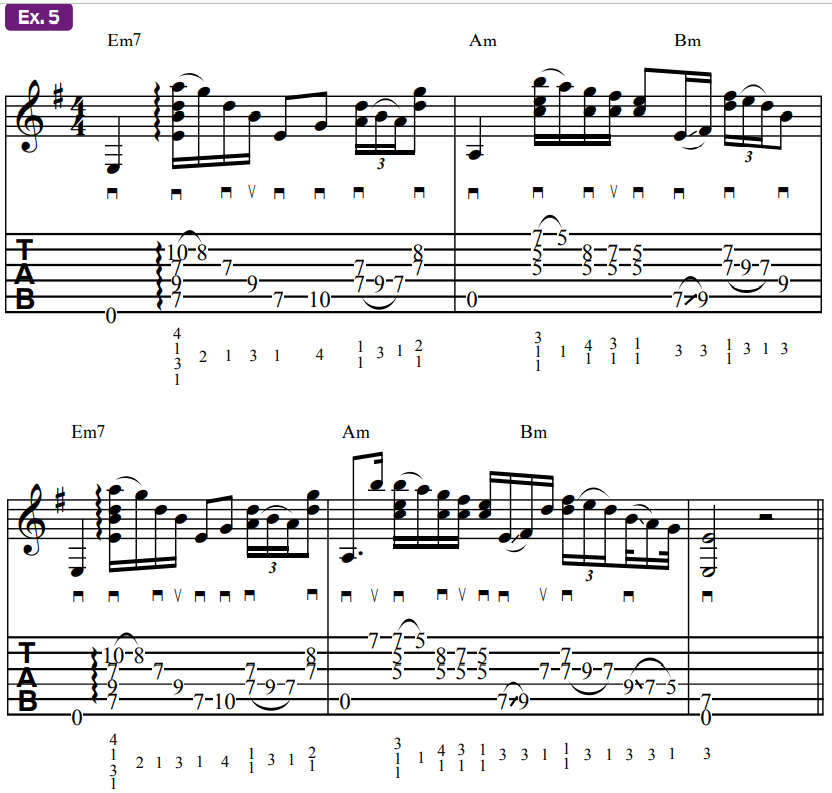

Thus far in this lesson, we’ve only dealt with major chords, but Hendrix was equally expressive with minor chords. His approach here often came down to availing himself to the tones of the minor and minor pentatonic scales.

Ex. 5 is inspired by a portion of his stellar intro to “Little Wing” (Axis: Bold As Love), using three minor chords: Em7, Am and Bm. Here you will use tones derived from the E natural minor scale (E, F# , G, A, B, C, D) when melodically contouring our chord progression.

Bar 1 is based around the Em7 chord (E, G, B, D). The key to this passage, in terms of technique, is maintaining the 1st-finger barre across the A, D and G strings at the 7th fret, which both provides the chord tones E and D and an added scale tone, A, played here on the D string, which comes in handy as both a melodic tone and as a tension against other melodic tones, as seen in beat 2.

In bar 2 you will move on to an Am chord (A, C, E), voiced with an open A root and your 1st finger barred across the top three strings at the 5th fret, forming a 1st-inversion voicing. From there, perform a pull-off from the high E string’s 7th fret with your 3rd finger and proceed to walk down the B string, from the 8th to the 7th and 5th frets, all while playing the 3rd chord tone, C, underneath, fretted with the barre.

Following this, you will slide up to 7th position, via the 3rd finger on the A string, straight into a Bm chord (B, D, F#), playing a double-stop hammer/pull before landing on the root of the chord.

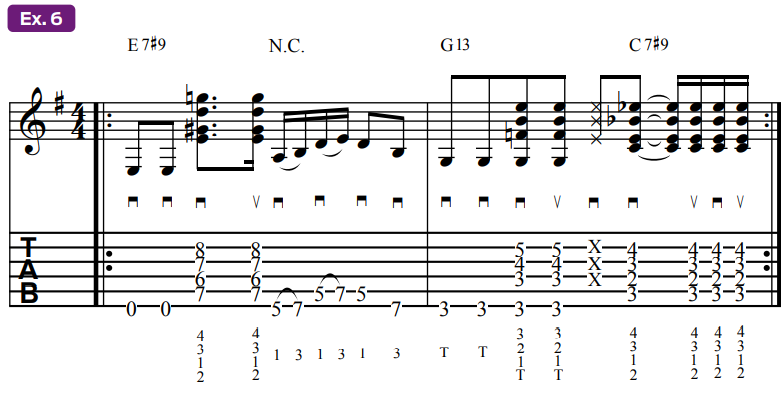

Jazzing It Up

Despite having no formal education in music theory, Jimi demonstrated harmonic sophistication and paved the way for contemporaries like Frank Zappa to further incorporate jazz harmony into the rock lexicon.

As a case in point, consider Jimi’s use of the E7#9 chord (voiced, low to high, E, G# , D, G natural), often called “the Hendrix chord” because of how frequently and prominently the guitarist used it in his music.

Jimi favored this chord because of its “split nature,” containing both a major and minor 3rds, or, as the chord symbol dictates: the major 3rd and the tension #9 above it. This major/minor duality perfectly encapsulates the spirit of Hendrix’s musicality; pushing boundaries and refusing to be defined by any rules of music.

Ex. 6 begins with an E7#9 voicing played on the middle four strings after an open low E root. Subsequently, you will play a single-note E minor pentatonic lick before plunging down towards a G13 chord (voiced, low to high, G, F, B, E) – the 13 chord being a common substitution for the 7# 9 chord – followed by C7# 9 (voiced C, E, Bb, Eb).

In addition to demonstrating the E7# 9 in all its glory, this chord progression is indicative of Hendrix’s penchant for playing around with key and tonality. While the key center E holds steady throughout, there is no firm distinction as to whether you are in a major key or a minor key.

And while the root motion of the progression clearly outlines an E minor scale, the chords themselves are all variations on dominant 7th chords – each containing the major 3rd and minor, or “flatted,” 7th chord tones – taking the typical 12-bar-blues approach of shifting I, IV and V dominant 7th chords to its harmonic extreme.

This chord methodology made for iconic riffs and a uniquely colorful sound, and laid the harmonic foundation for some of Hendrix’s greatest leads. Hendrix was equally fond of using major 6th and dominant 9th chords, as evidenced in such masterpieces as “Third Stone From the Sun” (Are You Experienced) and “If 6 Was 9” (Axis: Bold As Love).

The major 6th chord is built using the major triad (root, 3rd and 5th) with an added 6th degree, which can take the place of the 5th. The dominant 9th chord places the major 9th scale tone (located an octave above the 2nd) atop a dominant 7th chord – 1, 3, 5, b7, 9, although the 5th is typically omitted.

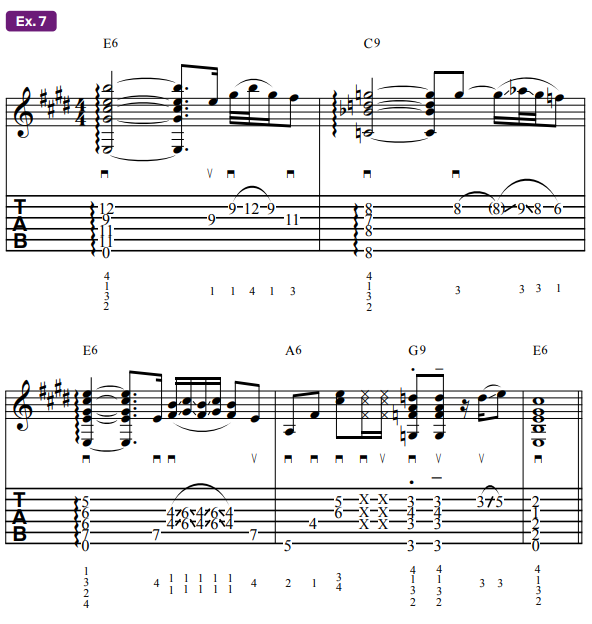

Ex. 7 alternates between these two chord forms in a soulful descending progression connected by melodic fills. You’ll start with an E6 chord, voiced E, G#, C#, E, B in 9th position, with an E major pentatonic lick leading you into C9 (voiced C, Bb, D, G), with your thumb fretting the 6th-string root.

Note that this voicing lacks the major 3rd, E, which is not uncommon. From here, you’ll work back to E6 in a slightly different voicing, played in 5th position (voiced E, E, G#, C#, E). A sliding double-stop based on the E major pentatonic scale (E, F#, G#, B, C#) guides you into the final stretch of chords: A6 (voiced A, F#, C#, E), G9 (voiced G, F, A, D, again without the 3rd), and one last E6 chord voiced E, B, E, G#, C#), played down in 1st position.

This example, in addition to being a particularly jazzy sample of Hendrix’s chordal prowess, also hints at the chord-melody playing style of Stevie Ray Vaughan, a Hendrix obsessive who would go on to become one of the all-time greatest guitarists himself!

Now that you can play chords with the same nuance and creativity as Hendrix, grab your Strat, dial in a warm but punchy clean tone and see what kinds of soulful, melodic chord-based riffs you can come up with.