Learn to play like Snarky Puppy's Mark Lettieri with the ultimate funk baritone guitar lesson

Capture multi–Grammy winning Mark Lettieri’s signature baritone funk guitar style by learning how to write riffs while combining registers and using different tunings, plus nested chordal embellishments and more

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It’s no secret that social media is a powerful vehicle for informing and influencing musicians. From ax-wielding upstarts attempting to show the world what they can do to established players giving curious fans a glimpse into their process as they flesh out ideas, the platform is ripe for opportunity. The catch is that you will be met with a discerning audience that has endless options to follow. To rise above the pack, it helps to have a thing.

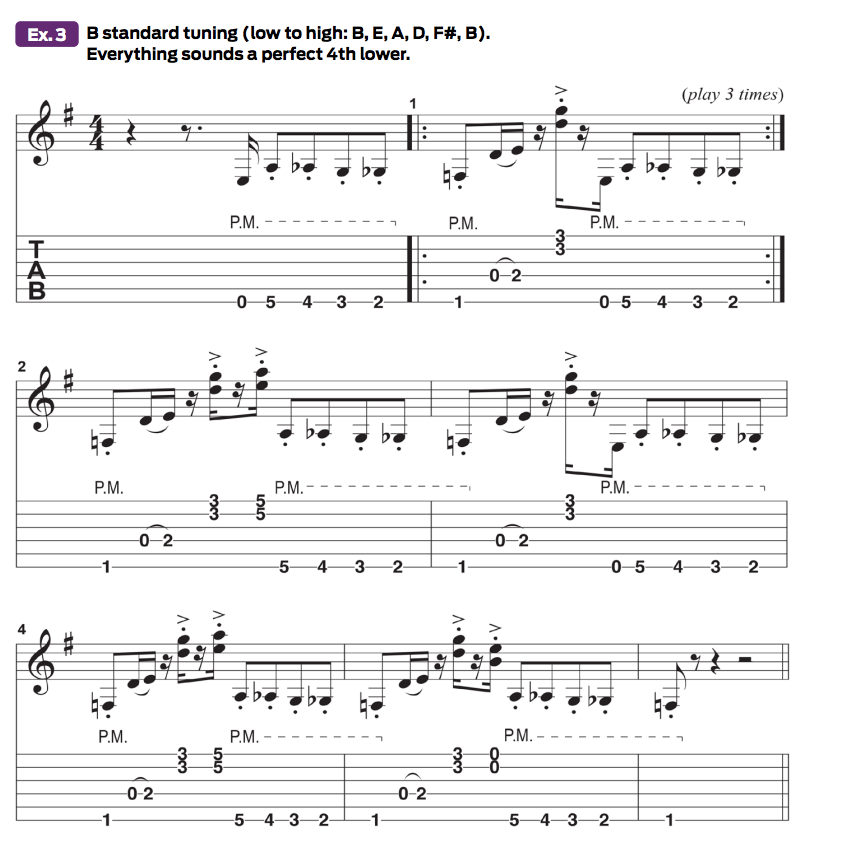

Enter the proverbial new sheriff in town: multi–Grammy-winning guitarist Mark Lettieri. With no interest in sounding like anyone else, and equipped with a production-line Danelectro baritone guitar — a six-string instrument with a longer neck and scale length that is meant for playing in much lower tunings than a conventional guitar — Lettieri showed us he had the goods when he started to drop a consistent barrage of infectious clean-tone, funk-style riffs played over what he calls “Minneapolis grooves.”

His playing made an immediate impact and fueled a pair of albums: Deep: The Baritone Sessions and Deep: The Baritone Sessions, Vol 2. In this lesson, Mark guides us through his world of baritone funk guitar using some choice riffs from both releases, played by the man himself in the very room where it all started.

Mark’s initial foray into baritone guitar playing dates back to 2008, when a producer recommended the option during a recording session. The simple textural part he tracked using an Ibanez Mike Mushok MMM1 signature baritone guitar planted a seed that sprouted every few years, starting in 2011, when his group Snarky Puppy were recording their 2012 album, groundUP.

Once again, by way of someone else’s vision — this time Pup’s Grand Poobah, Michael League — fellow Snarky guitarists Bob Lanzetti and Chris McQueen laid down a baritone part on a tune called “Minjor” using League’s Eastwood Sidejack guitar. Another few years passed before Lettieri adopted the baritone as his main guitar.

His next encounter came when he played League’s Eastwood baritone on Snarky Puppy’s 2016 album Family Dinner, Vol. 2, on which the Pups collaborated with the late David Crosby on a tune called “Somebody Home.” With baritone rooting itself in the Snarky Puppy production playbook, Mark took it upon himself to procure his first bari, the infamous Danelectro Baritone in black sparkle finish.

Equipped with additional various low-tuned guitars of varying scale lengths by Supro and Bacci, Lettieri continued down the rabbit hole with episodes of baritone playing, albeit ancillary, on his own solo efforts, starting with 2016’s Spark and Echo. But the infectious, groove-laden clean-tone playing that would become a staple in his burgeoning solo career can be traced to two pivotal scenarios.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

First, the bonus track “Jefe,” from Snarky Puppy’s Grammy-winning album Culcha Vulcha, featured Mark playing a bari for the opening chicken-picked ostinato, with a superb pocket and a cutting to-die-for clean tone.

That tone, as well as the attack Lettieri heard during playbacks as the session rolled on, inspired him to incorporate this new approach into his own guitar-playing video offerings on social media. He started with Facebook and eventually shifted to Instagram, using an MXR Bass Octave Deluxe, a Kemper Profiler amp and some choice synth bass playing in the rhythm tracks.

It was at this juncture that the journey to the critically acclaimed Deep: The Baritone Sessions and the Grammy-nominated Deep: The Baritone Sessions, Vol. 2 began.

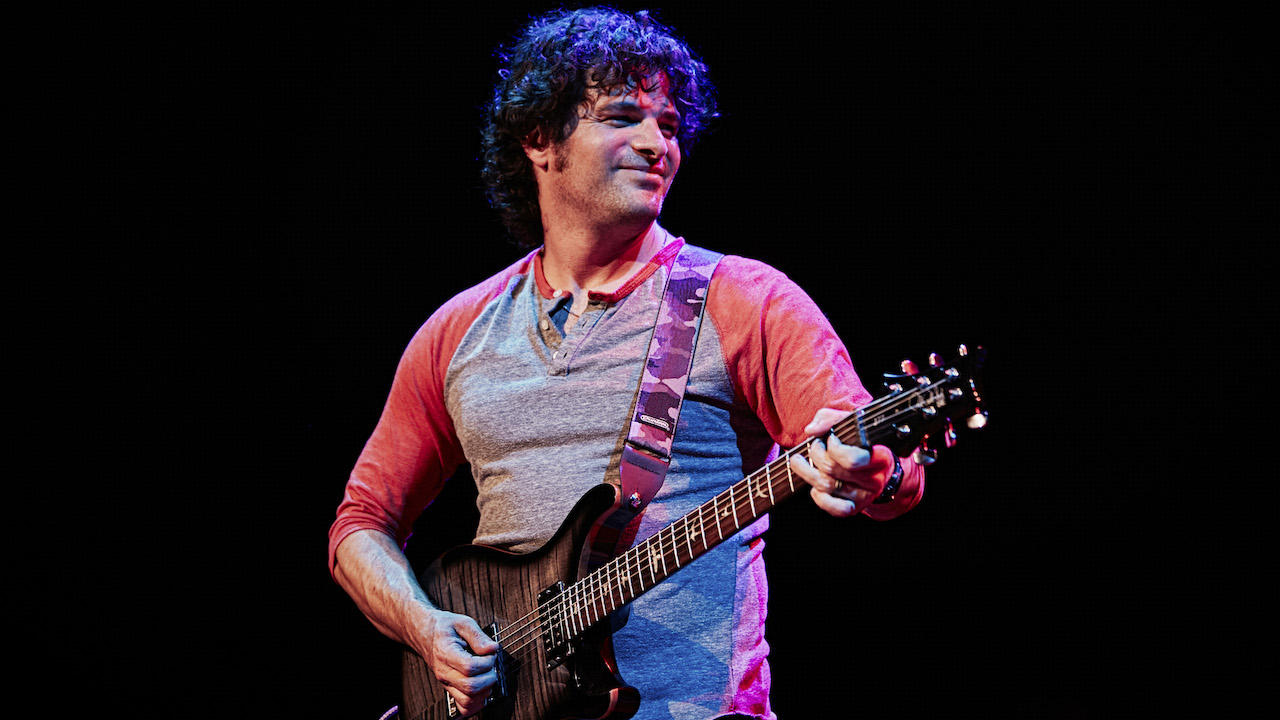

“The beauty of writing riffs with the baritone is you can combine registers to make things sound more interesting,” Mark states. To illustrate this concept, he fires off the verse to “Magnetar” (Example 1) from Vol. 2, using the syncopated E Dorian riff to show off the value in defining two distinct ranges.

To cover the highs, there are the biting high-string chords, such as the Em13 fragment played on the 16th-note pickup to bar 1, as well as the tritone on the second 16th note of beat 4 in bar 1. The single-note blues-scale riffing in the same measure provides the lows, along with the G, Ab and A major 3rd dyads that bridge bars 1 and 2.

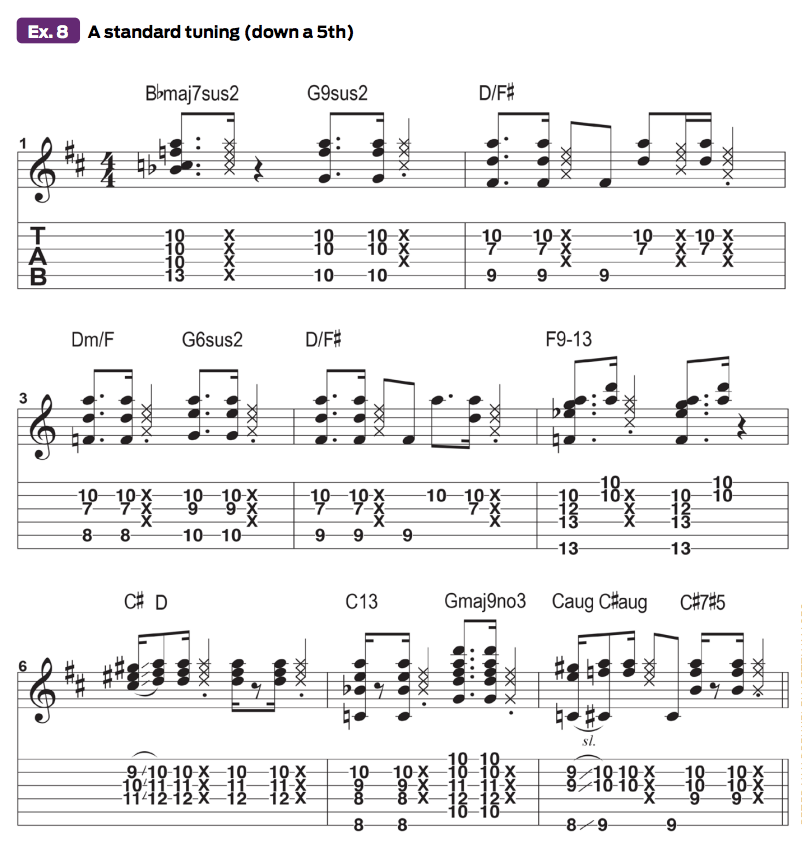

A note about pitch transpositions: In this first example and several that follow, Mark’s bari is in A standard tuning (low to high, A, D, G, C, E, A), which is regular (E) standard tuning transposed down a perfect 5th. While you visualize and think of all the notes and chords “normally,” as Mark does — as if you were playing a regular six-string in standard tuning — everything sounds a perfect 5th lower.

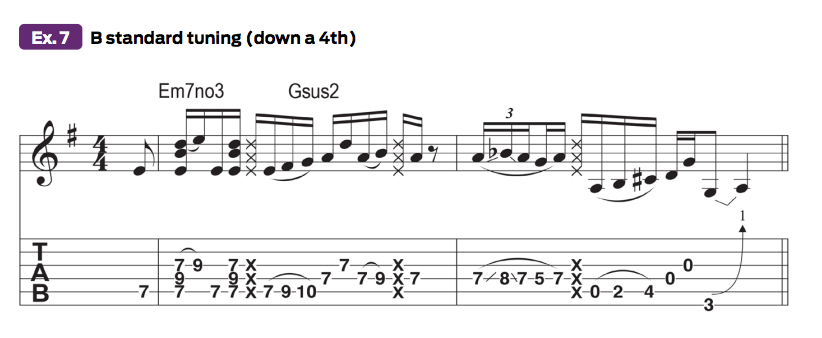

Think of it as “capo negative 7.” Other examples are in B standard tuning (low to high: B, E, A, D, F# , B), for which everything sounds a perfect 4th lower than written, or “capo negative 5,” if you will.

Lettieri goes on to explain, “I use both A standard and B standard baritone tunings. It depends on the particular song and where I want the pitches and chord voicings to sit, relative to the key.”

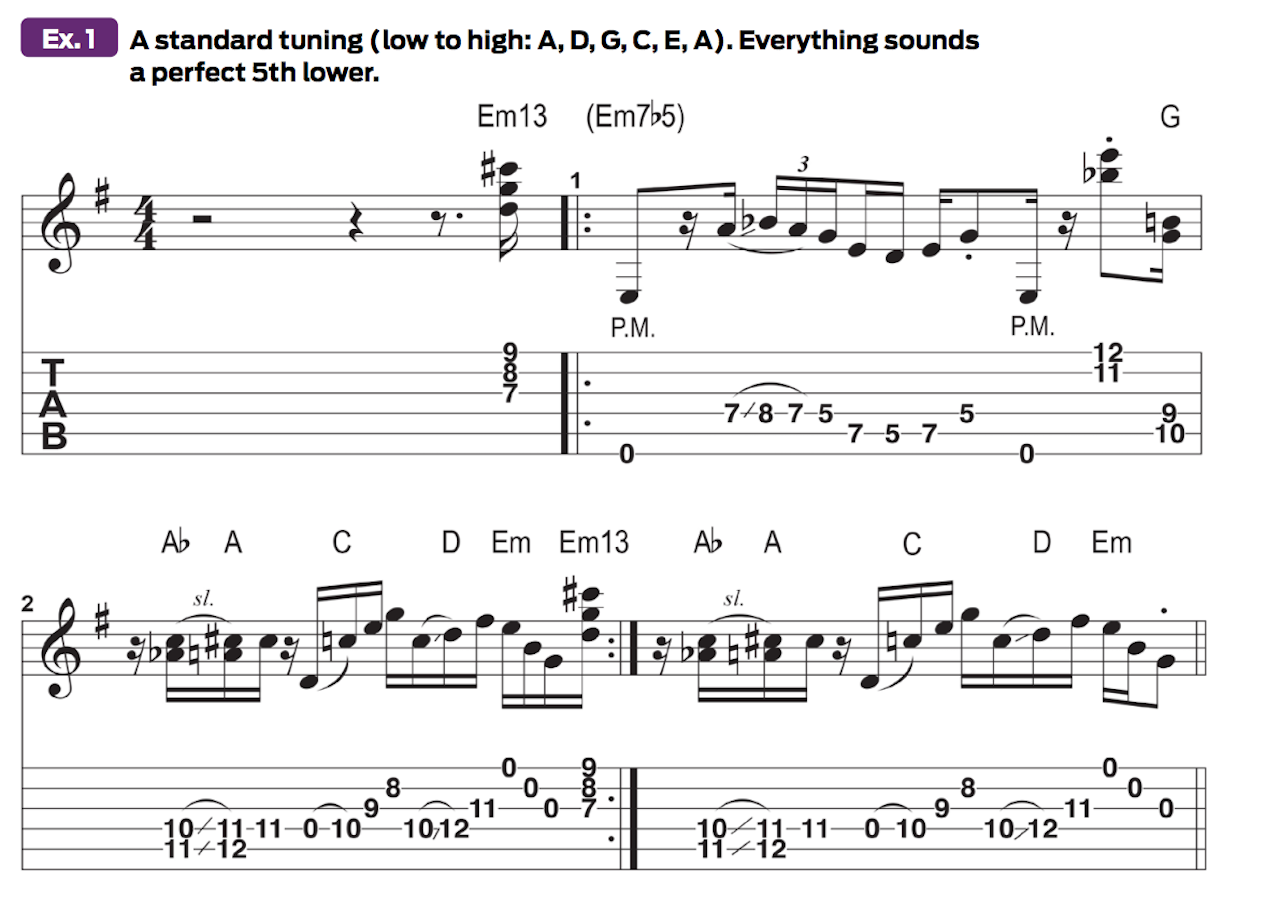

He illustrates this dual-option approach by offering two riffs in the different aforementioned tunings, the first being the main riff from “Daggertooth” (Deep: The Baritone Sessions), shown in Example 2. Played as if it were in the key of B minor, using A standard tuning, the riff sounds a 5th lower, in the key of E minor.

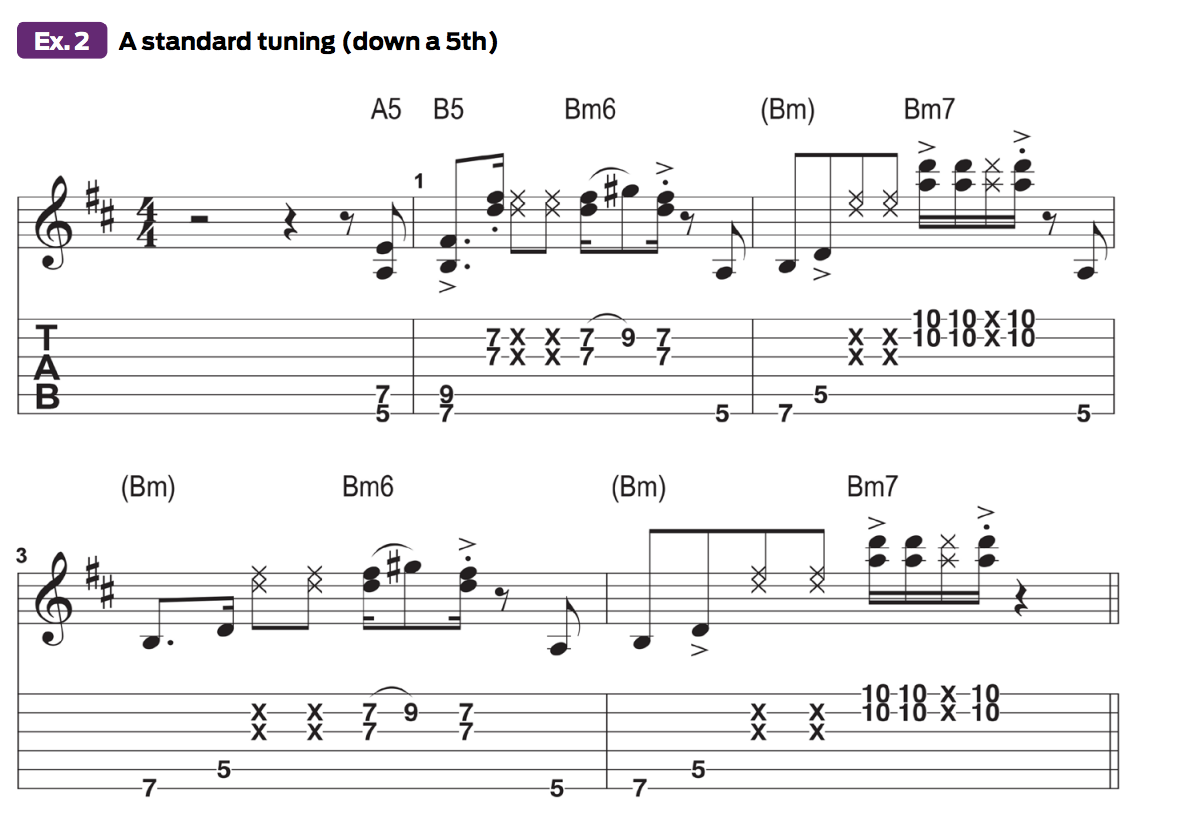

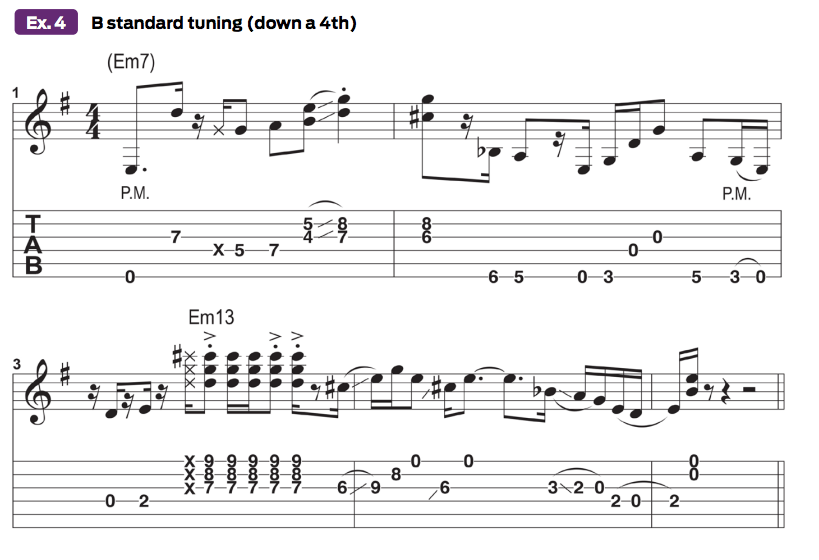

Next Mark plays another selection from that record, the chromatically descending motif in “Gigantactis” (Example 3), for which he employs the higher B standard tuning, which transposes his E-minor riff down a 4th, to B minor.

Musically, notice in both riffs how Mark employs the tried-and-true call-and-response phrasing construction and uses accented staccato perfect-4th dyad stabs played on the 1st and 2nd strings — a staple in his lauded funk rhythm guitar playbook.

Mark adds, “When I’m writing tunes on baritone, I want to explore the low end while keeping the high end present, to keep it bright and funky.” Notice the guitarist’s use of palm muting (P.M.) on some of the low-string notes, which shortens their duration and keeps things tight by preventing these notes from ringing along with the higher notes and chords that follow.

Shifting gears, Mark explains, “In some songs, the parts are just riffs, such as the verse in ‘Gigantactis’ or the chorus in ‘Tidal Tail,’ from the second record.”

Example 4 addresses the former, as it lays out the tune’s strategically spaced E Dorian riff that continues to follow the guitarist’s full-spectrum baritone ethos, coupled with some open notes on the higher strings that he intentionally allows to ring.

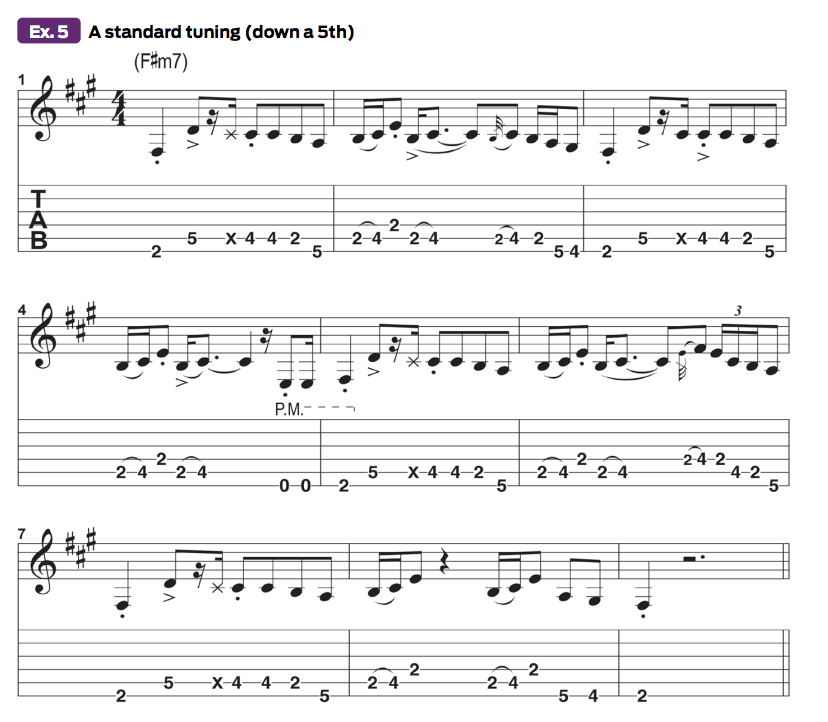

Example 5 maps out a 2nd-position F# Aeolian riff Mark plays in “Tidal Tail,” which he performs almost exclusively with downstrokes.

At this point, if you’re thinking about how the bass player fits in the equation, according to Mark, “Wes [Stephenson] either doubles or counters what I’m playing on his five-string. In many cases he’s the human octave pedal.”

Lettieri goes on to summarize, “I love riffs. And because the baritone is so engaging, you don’t need a melody if the riff is good.”

The guitarist adds, “Don’t lose sight of the fact that you’re essentially playing a hockey stick.” Since the early days of the Dano, Supro and Bacci baritone axes, Mark’s cache of low-tuned guitars has expanded to offerings from Hybrid Guitar Co. and Paul Reed Smith.

The main difference between whichever stick he chooses these days and his many conventional, albeit smaller, counterparts (including his signature PRS Fiore) is twofold: scale length and string gauge. While a standard electric guitar’s scale length — the distance from the bridge to the nut — generally falls between 24 ¾ and 25 ½ inches, baritone guitars range from 27 to 29 inches.

To facilitate the lower B and A standard tunings, you need to use thicker string gauges. Many electric guitarists use string sets that range from .009–.042 and .010–.046 inches, with a traditionally unwound (plain) 3rd string, whereas comparative baritone sets come in at .012–.052 and .013–.056, and almost all boast a wound 3rd string, which is harder to bend.

I love riffs. And because the baritone is so engaging, you don’t need a melody if the riff is good

Mark goes even deeper and turns to Dunlop for custom sets that go, low to high, .014, .018, .026, .044, .056 and .068.

Mark’s baritone playing celebrates everyday standard guitar playing approaches and techniques while reaping a unique benefit. As he notes, “When playing a bari with a pick, the tone and attack you get are something only a baritone can deliver.”

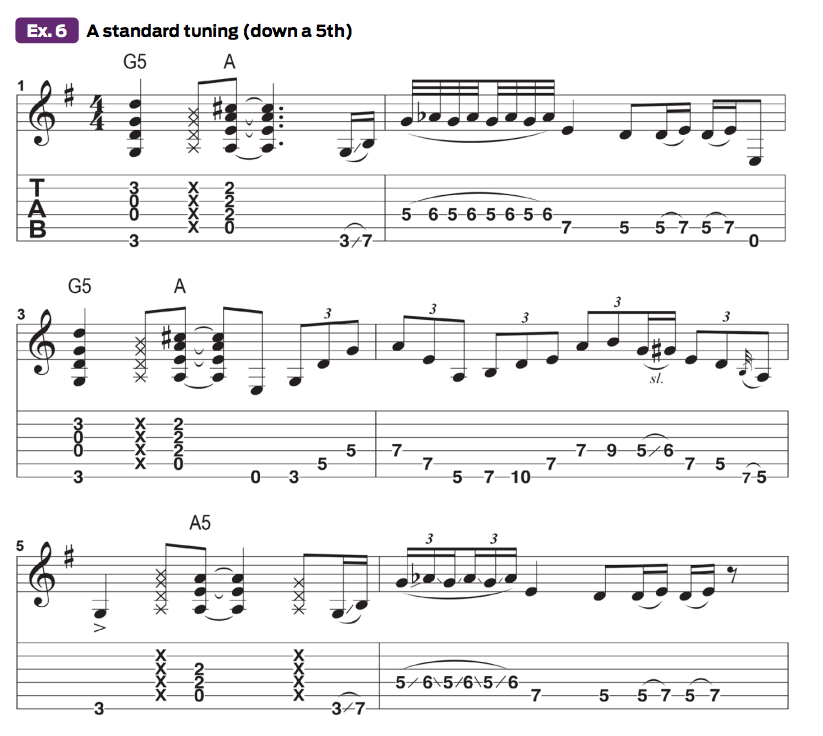

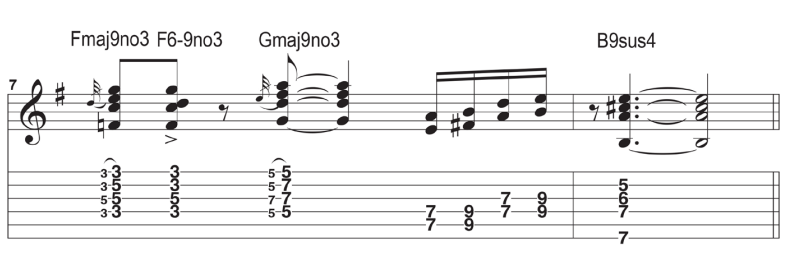

Example 6 showcases this with the eight-bar chorus from the Vol. 2 selection “Voyager One,” which features open-position chords with added sonic depth, successions of rapid hammer/pulls and legato finger slides, and some Hendrix-y nested grace-note inflections applied to a pair of Steely Dan–approved maj9(no3) voicings.

Example 7 is an excerpt from the intro to “Stoplight Loosejaw” (Deep: The Baritone Sessions) and offers another cool instance of Lettieri’s refined use of nested chordal embellishments, this time with hammer-ons applied to ringing chords with open strings. Mark performs this figure with hybrid picking, using his pick in conjunction with his middle and ring fingers to sound the notes of the Em7 chord voicing simultaneously, as a keyboardist would.

Adopting the baritone guitar not only bolstered Lettieri’s already well-established profile as a player with myriad celebrated attributes; it also helped shine a light on him as an artist keenly aware of his surroundings.

He found inspiration in his daughter’s Fisher-Price Laugh & Learn and its four-key colored keyboard, where a lone red key served up the concert-pitch D note that would become the top-note voice-leading anchor for the harmonic movement in the song “Red Dwarf” (Deep: The Baritone Sessions, Vol. 2).

Example 8 provides the roadmap for this baritone chord-de-force, which is made up of variations of triads and tetrads (four-note chords), some being must-know sus2 voicings for anyone looking for a modern fusion sound.

Throughout his journey through the Deep albums, Mark uncovered more than a few baritone guitar tenets that he abides by today, some of which are closely associated with his notable good-natured quick wit. For starters, Mark affirms, “You can have a song be a bass line because it’s not gonna feel like a bass line, because it’s not on a bass.” He adds, “A baritone should just be a baritone,” as he makes it clear that he “rarely plays above the 12th fret.”

Mark was also forthright about the physicality involved in playing these long-necked instruments, saying “it’s actually work.” Live, Lettieri uses his PRS SE 277 Baritone with Lollar P90 pickups, when not playing his signature Fiore. He plays them both with Dunlop 1.0 mm celluloid picks while plugging into amps that make use of 12-inch speakers, have at least 40 watts of power and allow for plenty of clean headroom.

He also adds either an RAF Mirage or Jackson Audio Blossom compressor in his signal path between the guitar and amp to optimally manage the wide dynamic range in his playing and the differences in output levels among his various guitars.

Out by Midnight: Live at the Iridium by Mark Lettieri is out now and available to buy or stream

Chris Buono is a top-selling TrueFire Artist with nearly 50 instructional videos, and a featured instructor on guitarinstructor.com. Bookending his years as a Berklee professor, he authored eight books, including the popular Guitarist’s Guide to Music Reading and his most recent publication, How to Play Outside Guitar Licks.