Introduced in the 1970s, Morley’s PWF Power Wah Fuzz Pedal Was the Final Word in Unrelenting Fuzz-Wah Tone

Swathed in shiny chrome, they were presented as the best of the best in the effects revolution’s boomingest decade

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you were seeking power in your fuzz-wah tones in the mid-to-late 1970s, nothing delivered in a more high-voltage fashion than the Morley PWF. The name was short for Power Wah Fuzz, and the pedal was long on aggressive, hard-charging tone.

Shining through a crowded field of stompboxes, Morley pedals were big and built to last. Swathed in shiny chrome, they were presented as the best of the best in the effects revolution’s boomingest decade. Morley products were often referred to as “the Cadillac of effects pedals,” although the company frequently advertised them with a Rolls-Royce grille subtly hovering in the background, a notion purportedly inspired by the fact that Ike Turner used to drive his own Rolls to the Morley factory outside L.A. to purchase pedals directly from the maker.

Either way, they were priced accordingly. The company’s first big success, the RWV Rotating Wah Volume pedal of the early ’70s, listed at a whopping $259. That might sound about right for a boutique pedal in 2023, but the figure comes into perspective when we consider that a standard blond Fender Telecaster listed for $283 at the time, plus $65 for the case. The impression was that Morley pedals were serious gear for professional players – or at least for those who might need to take out a stage invader with one swing of the brick-like effects unit.

The original manufacturer of Morley pedals was Tel-Ray Electronics, a TV and radio repair company in Los Angeles, founded by Raymond and Marvin Lubow in 1946. The brothers were born in the Bronx, New York, and served in the military in WWII, after which they decided to head to sunnier climes and start their own business.

Ray’s training in electronics at Manhattan’s Hebrew Technical College, combined with his service in the Army’s Signal Corps afterward, set him up as the operation’s creative mind, while Marv’s business acumen made him a valuable partner. Tel-Ray segued from repairing to inventing and manufacturing original products. As the venture moved into the 1960s, Ray became more and more interested in how electronics were directly helping artists make music.

This led to him developing an oil-can delay for use with guitar, keyboards and voice in the mid ’60s. He later adapted it into an effect capable of mimicking a rotary speaker-style vibrato. Dubbed the Rotating Sound Synthesizer, it was the precursor to the Rotary Wah Volume pedal. Both versions were made using a can filled with electrostatic fluid and a pair of brushes that would record and playback the instrument signal to and from the interior of the drum, with the delay time or rotary speed determined by the drum’s revolutions.

In the late 1960s, the transmutation of this effect into pedal form, with a rocker to control the rotary speed, led the Lubow brothers to the brand name by which their creations would henceforth be known. As the story goes, Marv and Ray jokingly quipped that while the big name in rotary speakers was Leslie, their pedal delivered more. Thus, the Morley name was born, leading to the slogan, “Why settle for less with a Leslie when you can get more with Morley.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

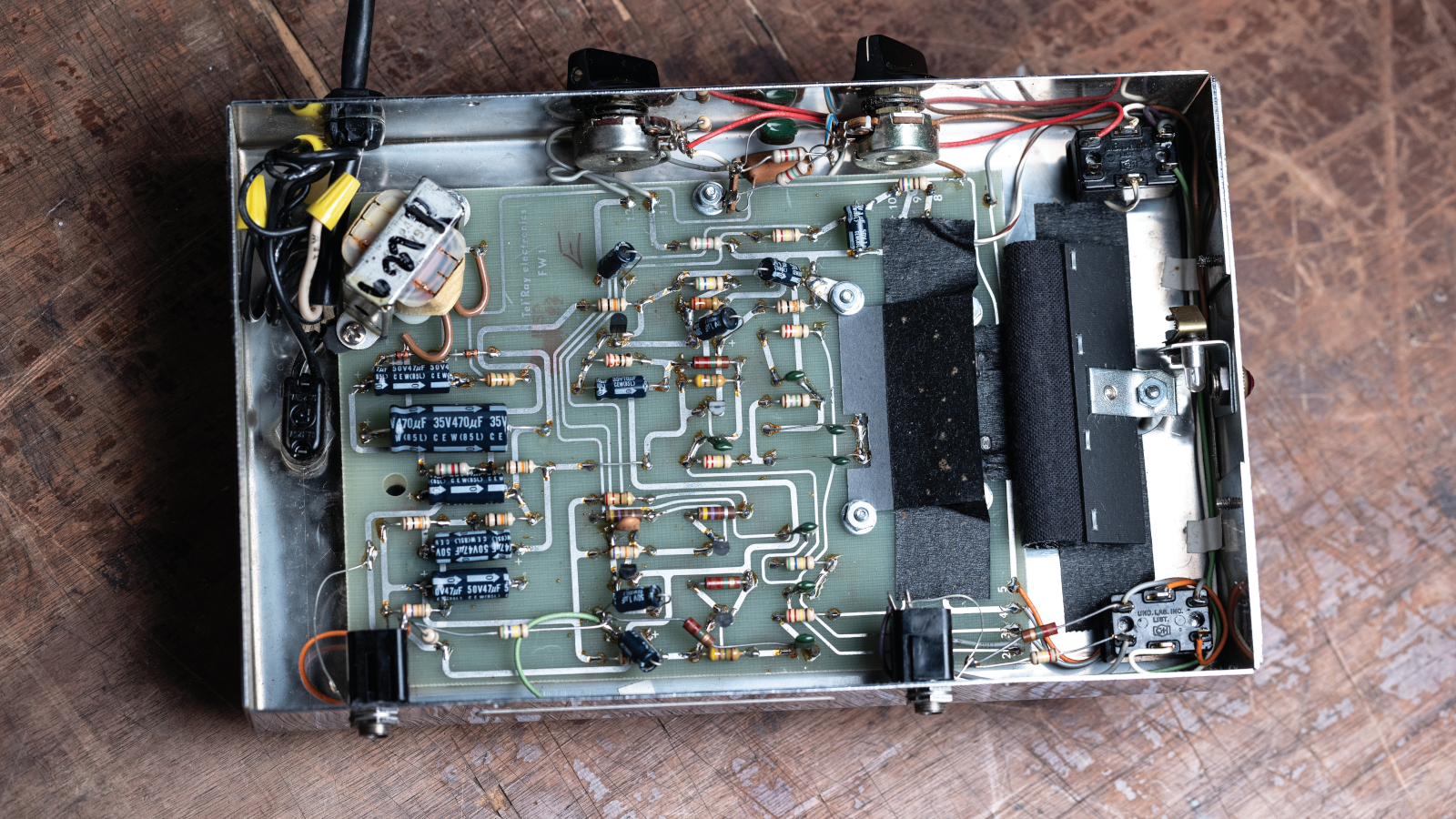

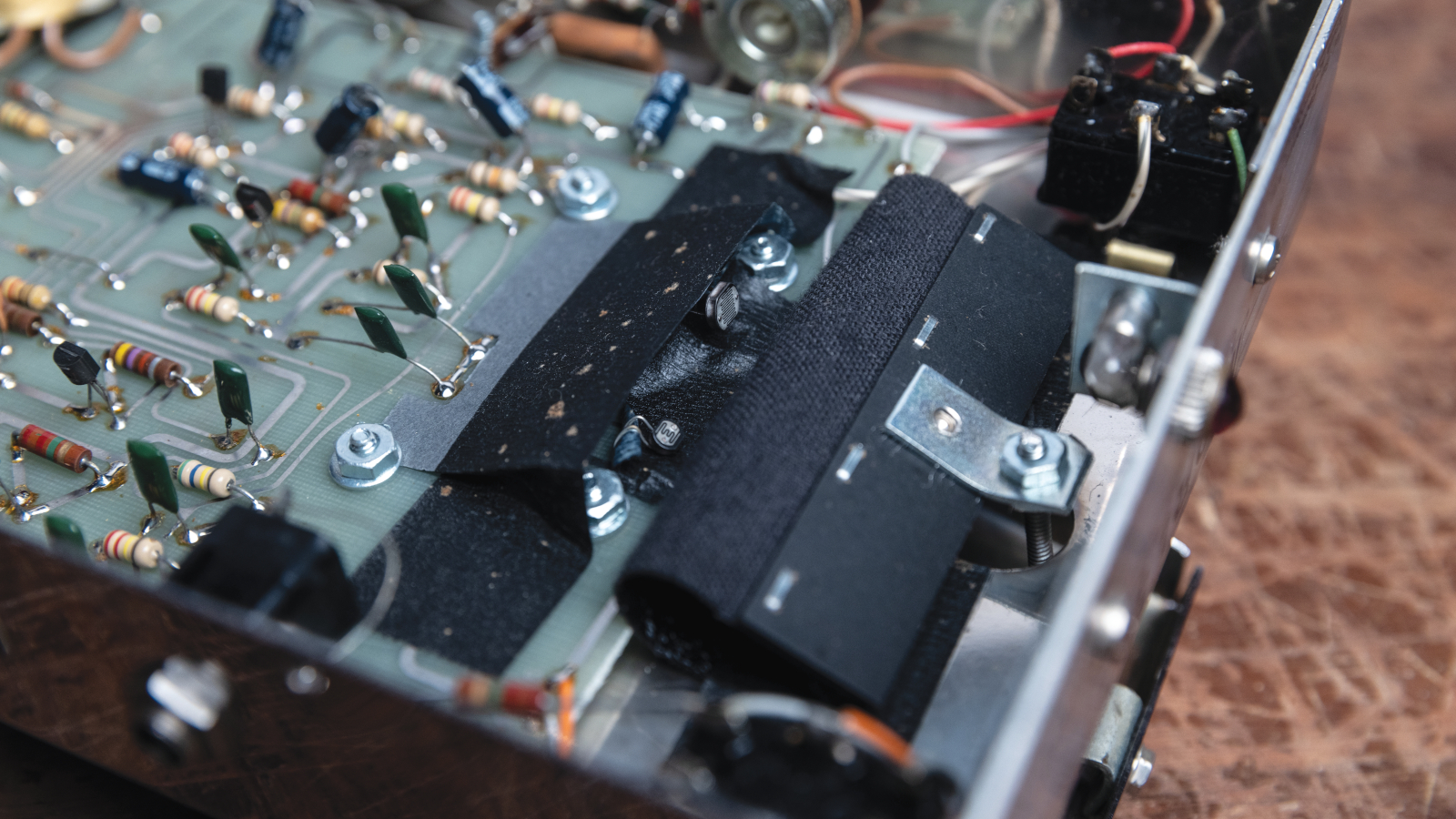

As our featured PWF pedal from circa 1977 reveals, Morley’s unusual approach didn’t stop with echo and rotary-speaker effects – they did everything differently. For example, other companies’ rocker pedals were entirely mechanical, moving a potentiometer by means of a toothed rack and gear. Morley instead used a light-dependent resistor (LDR). Moving the rocker pedal lifted and lowered a shade that affected how much light reached the LDR, which in turn changed the response of the tone-filter circuit. Having no direct mechanical interaction with the electronic components resulted in less wear and tear on the parts and no scratchy potentiometers. The rocker itself appeared more like the chromed, treadle-topped accelerator of an American muscle car, and was built to withstand similar abuse.

Combining high quality, great sound and roadworthiness, Morley pedals were found under the feet of many pro guitarists in the ’70s and ’80s

As for the sound, the fuzz from the PWF was brutally thick and aggressive, capable of plastering enticingly raspy distortion all over your tone. In addition to controls for intensity and tone, it offered the nifty option of using the rocker pedal to blend the desired amount of fuzz into the clean signal, or merging the pedal’s two effects for an all-out fuzz-wah attack. Rather than using the toe-down position to trigger the effect, as on many traditional wah-wah pedals, the PWF had individual on/off foot switches on either side of the rocker’s heel position, and a sturdy power switch at the toe end.

The name ‘Power Wah Fuzz’ might imply three effects, but from Morley’s perspective the pedal was all about power. Notably, the PWV didn’t run on wall warts or batteries – you plugged its hard-wired power cord straight into a wall socket, delivering enough juice via the internal transformer to supply upward of 60 volts to some parts of the circuit.

Combining high quality, great sound and roadworthiness, Morley pedals were found under the feet of many pro guitarists in the ’70s and ’80s, and several other notable users ever since. The PWF user cited most often is late Metallica bassist Cliff Burton, while Steve Vai has long been a user of Morley wah-wahs and has rocked his signature Morley Bad Horsie wah pedal for years. Other signature units include the Mark Tremonti Power Wah, George Lynch Dragon 2 Wah and DJ Ashba Skeleton Wah, all now made by the Morley Product Group in Carpentersville, Illinois.

But they all owe their existence to the innovation and success of early Morley pedals like the PWF.

Essential Ingredients

- Heavy duty chromed steel enclosure and rocker pedal

- Individual foot-switches for fuzz and wah-wah

- Controls for fuzz Intensity and tone

- Internal light-dependent resistor (LDR) circuit for potentiometer-free wah-wah control

Dave Hunter is a writer and consulting editor for Guitar Player magazine. His prolific output as author includes Fender 75 Years, The Guitar Amp Handbook, The British Amp Invasion, Ultimate Star Guitars, Guitar Effects Pedals, The Guitar Pickup Handbook, The Fender Telecaster and several other titles. Hunter is a former editor of The Guitar Magazine (UK), and a contributor to Vintage Guitar, Premier Guitar, The Connoisseur and other publications. A contributing essayist to the United States Library of Congress National Recording Preservation Board’s Permanent Archive, he lives in Kittery, ME, with his wife and their two children and fronts the bands A Different Engine and The Stereo Field.