"What did we do when the record company asked us for a disco hit? We gave them Highway To Hell!" An archive interview with AC/DC's Angus and Malcolm Young

20 years ago, back in 2003, Guitar Player sat down with Angus and Malcolm Young to look back over their career. Prompted by AC/DC's induction in that year's Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame it became a funny and insightful trip through their back catalog, made all the more poignant today with Malcolm Young's death back in 2017.

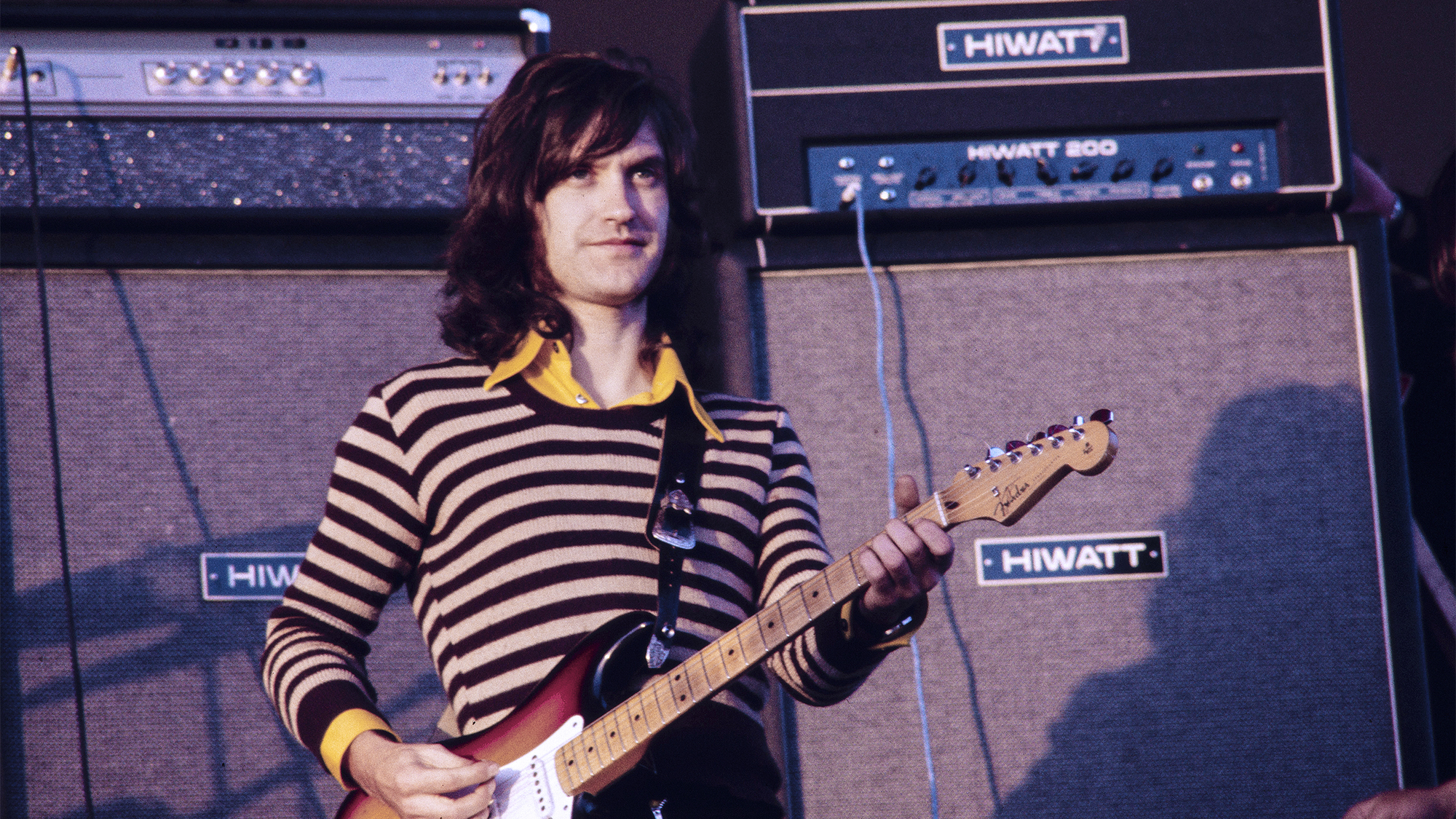

In many ways, it was a normal night for AC/DC. Guitarist Angus Young donned his famous schoolboy uniform, stepped onstage backed by the mighty rhythm playing of his older brother, Malcolm, and proceeded to electrify the crowd like a Gibson-wielding demon. However, for perhaps the first time in AC/DC’s history, Angus wasn’t the only one in the building sporting a tie.

“It was our first restaurant gig,” cackles the guitarist, “and hopefully our last.”

But while the audience was full of white tablecloths and black tuxedoes, this was by no means your average restaurant gig. It was March 10, 2003, at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City, and AC/DC was being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The irony of it all wasn’t lost on Angus.

“The whole thing was kind of amusing,” he says about playing such a posh room, “because it was exactly the type of place that would normally throw us out!”

But no one was going to throw the Young brothers out of this ceremony—especially since they took a fistful of stock, Chuck Berry-style rhythm and blues licks and created one of the most identifiable rock-guitar styles of all time. In fact, the duo’s imprint on rock and roll couldn’t be more obvious if the generations of guitarists they’ve influenced had “Angus and Malcolm were here” branded on their foreheads.

Here, the Young brothers reflect on their long, adventurous journey to the Hall of Fame and the albums that got them there…

How did it feel being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

Angus: Weird—you wouldn’t really think of us in an institution like that, you know? You’d think of us somewhere else, like maybe in the Hall of Insane.

Looking back on the three decades of hard work that landed you in the Hall of Fame, is there anything you wish you had done differently?

Malcolm: No, I think we’ve done just what we’ve wanted to do. We’ve always been forceful in getting what we wanted from record companies, management, and everything else. If we had done something differently, we might not still be around. If we’d have jumped on one of the bandwagons, it might have been costly for us, like it was for many other bands. That’s why we never changed hairstyles for the latest fashion or embraced the latest musical trend. We just stuck to what we always were.

Angus: It’s like when the music of the day dictates that the guitarist has a wah pedal or a tremolo effect or something. You listen to it five years later, and go, “Jeez, it sounds so dated.” We never did that.

Ever have a temptation in the ’70s to put a disco beat on any of your records?

Malcolm: No, but a few other people wanted us to do exactly that. We literally had record company people asking us for a disco hit!

How did you deal with that?

Malcolm: We gave them Highway to Hell.

How do you respond to critics that say AC/DC’s sound hasn’t evolved much over the years?

Angus: I think what those people are really saying is that we’ve never changed our style.

Let’s look back on some of the recording sessions for the albums that have now been remastered. What do you guys remember most about tracking High Voltage?

Angus: That was our first real album, and it was the one that defined our style. Up until that point, all we had really done was a lot of touring around Australia, so it was great to get into a studio and really hear how we sounded. What was impressive about that album was that it sold on word-of-mouth alone, because music on Australian radio at that time was really soft.

Air Supply, huh?

Angus: Worse than that!

What did you guys learn from the Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap sessions?

Angus: Never to do an album that way again! [Laughs.] The “dirt cheap” part of the title says it all.

What were the Highway to Hell sessions like?

Malcolm: That’s when we first met up with [producer] “Mutt” Lange, and, to be honest, recording that album went really smoothly for us—even though the budget was tight, and we had to put the whole thing together in about three weeks.

How did Lange prepare you for the sessions?

Malcolm: He’d have us play our songs, and then he’d record them on his little tape recorder. When he came back the next day, he’d have all his ideas organized, and he’d tell us exactly where he wanted things rearranged, what parts he wanted changed, and where little breaks could be added.

Angus: For example, he put in that great break near the end of “Highway to Hell” where the band drops out, and I scrape the pick down the strings. He created the hole, and I filled it. I’m the dentist. [Laughs.]

Before that, your albums were produced by your older brother, George Young, along with Harry Vanda. What was different about working with Lange?

Malcolm: George and Harry had free studio time, so things were usually pretty relaxed. They’d say, “Come on guys, let’s go in and see what we can come up with,” and we’d end up working out arrangements while we were tracking. Sometimes we’d change a song ten times in a night. And if we thought a take was good, we might leave a weak snare or a rough-sounding guitar on it. But Mutt was very strict about making sure no bad tracks got through.

Did you have any concerns about switching to Lange?

Malcolm: Having never worked with him before—and with him being fairly new to hard rock at the time—we were worried his sounds might be a little too clean for us. But when he mixed everything, it came alive. It wasn’t as raw as before, but it sounded raw enough. And it was punchy.

Did you learn any mixing tricks from him?

Malcolm: Well, he didn’t like the room we were tracking in, so he recorded everything very dry. Then, when it was time to mix the album, he switched to another studio, pumped the drums and guitars through some P.A. speakers, recorded that room’s sound, and blended it into the mix for added ambience. We thought that was quite clever. When we heard it all together, we were knocked out.

What was the emotional climate like jumping back in the studio to record Back in Black after losing Bon Scott?

Angus: It was a bit of a do-or-die effort. We really didn’t know what would happen with that album. Luckily, Malcolm and I had a lot of good song ideas—a lot of which Mal had came up with during the Highway to Hell tour.

Malcolm: Putting those riffs together was really all that kept us going. We were in a fog after Bon died, and we had to do something, you know—just to keep ourselves alive. But we had ideas, and working on them was the only light at the end of the tunnel for us.

Did Lange help you through?

Malcolm: Yeah—although he suffered, too, because he liked working with Bon. But he kept us going by keeping us on the go. We didn’t have time to stop and think, which was good, because once you thought, it hurt.

Back in Black was mixed so well, it’s hard to imagine remastering could make it sound better.

Malcolm: I must say, the new CDs sound a lot better, and the fans seem to agree. But, to be honest, I prefer vinyl because it has that warmth. They’re also bringing out all our albums on vinyl, which is great because that’s our era.

Angus: Plus, we like the big covers! And I like the hiss when you first put the needle on a record. You can always tell just how loud it’s going to be. You don’t get that with CDs. They just suddenly go “Wahhh!”

Let’s talk about some riffs. Who wrote the three-chord theme to “Back in Black”?

Angus: Mal had that all sketched out on tape with just an acoustic guitar. He even had that little descending lick between the chords. To this day, I still don’t know if I’ve got it right, because it sounded so huge on his demo.

Malcolm: Oh, he got it right.

How did you guys come up with “Highway to Hell”?

Malcolm: Well, that was Angus. He had those chords there at the start, and I said, “Whoa, that sounds really good.” But then I wondered, “What can we do with the drums?” So I got on the drums and put down this straight beat right through it—which most drummers would never do. But it quickly locked in, and the song just flew out. It was done about five minutes later.

Angus: Yeah. We were in a rehearsal room in Miami, and Mal was banging on the drums. I went to the toilet for a minute, and I started singing the words “highway to hell” for the chorus. And then Bon put his pen down and came up with the verses.

Everybody talks about AC/DC’s huge guitar sound, but perhaps one reason your riffs sound so massive is that they often have big holes in them that let the drums jump through.

Angus: It’s kind of like a good book. Part of it’s written, but most of it is a mental picture that’s created when your imagination takes over. Those spaces make things sound bigger, because you fill them in with your mind.

Do you write with the drums in mind?

Malcolm: Yeah—that’s the main thing for us. If the drums aren’t right, it ain’t gonna work. We’re both toe-tappers. When we sit down and play guitar, our feet are going.

Angus: Usually, when we’re playing riffs like “Highway to Hell” or “Back in Black,” we hit the chord, and then tap our feet where the snare would be. We’re really two frustrated drummers. But if you listen closely to our stuff, it’s actually the vocal that holds it all together—like on “You Shook Me All Night Long.” You’ve got the guitar playing in the groove with the drum beat, but it’s the lyrics that push it along. We always look for a melody you can sing. It’s okay if it sounds pretty at first—we’ll make it rough later.

Malcolm: It’s always the songs that are good, not just the riffs.

One way you seem to make guitars sound huge—like on “You Shook Me All Night Long” and “Highway to Hell”—is by having the bass wait until the chorus to come in.

Angus: See, we are subtle after all! Pretty deceptive, huh?

“You Shook Me” is remarkable in that it’s possibly the only hard rock song that gets spun regularly in dance clubs.

Malcolm: That’s right. AC/DC is really a dance band. We got our start having to get people to dance in the small clubs in Sydney. The managers would say, “If you want to work here again, get people out on the dance floor so they sweat and buy more beer.” We’ve basically stuck to that.

When many people think of AC/DC, they think of huge power chords. But not everybody realizes you use more open chords than barre chords.

Malcolm: The big, open G chords are great. Just be careful not to hit too many of the thin strings when you’re strumming. Stop your strum at about the G string, and it just rounds bigger. The tone is crucial, too, because there’s a fine line between being too clean and too distorted. It’s all about getting that perfect edge going with your Marshall, rather than having the chords sort of fart through.

You’re known for using a fat set of strings, Malcolm—including a wound G.

Angus: He uses barbed wire for a G string.

Malcolm: I use Gibson Sonomatics [later sold under the name “L-5”] gauged .012-.058. I switched to that gauge three months after the band formed, and I’ve never changed. I first went to them because we’d been having tuning problems. I thought, “Well I’m just playing rhythm, so I’ll get the thick strings and keep my tuning solid.” Then I realized that we sounded better, too, because the rhythm sounds were bigger. You get more volume from thick strings. And they do stay in tune better when you’re digging in as hard as I do. I rip the chords as hard as I can so the wood really resonates. There’s no finesse involved.

Angus: He doesn’t tickle it [laughs]. And if you actually watch him, he goes through so many guitar picks! It’s a real piece of art—all those picks lying around him at the end of the night. They’re all just shredded.

Malcolm: On “For Those About to Rock,” we do a big, extended ending, and I might tear up four heavy picks in that closing section alone. They just burn down. You can literally smell them in the air.

And you guys are still sticking to your same guitars?

Malcolm: They’re like extra limbs, those guitars. I’ve used my [1963] Gretsch Jet Firebird from day one, and, in the studio, Angus uses the same Gibson SG that he always has. But he doesn’t bring that one out on the road because it’s a lot more delicate than his others. It has a really thin neck, and with the hammering he gives his guitars, it doesn’t stay in tune for long.

Do your SGs get beat up, Angus?

Angus: Believe it or not, the biggest problem is that they get waterlogged.

With sweat?

Angus: Yeah. The screws and pickups start rusting, and the guitar techs are always having to open them up and clean them out.

What about amps?

Angus: I’ve found that Marshall 50-watters produce the best sound in the studio. I can get more drive out of them—which also suits the tonal difference in our guitars. My SG has a more mid- to top-range sound, and Mal’s guitar has more bottom-end. Onstage, however, I usually play through four 100-watt Marshalls with the volume just over halfway up.

Malcolm: I’m running through three 100-watt Marshalls, but the only one that gets miked is my early-’60s Super Bass, which I’ve had forever and use in the studio, as well. Even when we’re doing arenas, I’m rarely above two. If those amps are on three, that’s a loud night for me. I’m up just enough to put that sharp edge on the chords. Live, Angus plays a little bit more distorted than he does in the studio, so that he can use the volume knob on his Gibson to pump up the drive for his solos.

Angus: A big reason we’ve ended up with such huge rigs is because when we were still doing opening slots, we’d often get shortchanged at soundchecks. The guitar amps would usually be the last things to get miked, so we said, “Let’s make sure we get heard.”

Malcolm, you’ve watched Angus run around the stage for decades now. Has he slowed down any?

Malcolm: He’s only getting more hyper. The only time he’s still is in that ten minutes just before we go on. He just goes completely silent.

What’s going on in those ten minutes, Angus?

Angus: I’m just finding the demon inside [laughs]. I think we all carry around someone else who’s bursting to get out of us, and that’s what usually happens with me. Plus, I’m a chain smoker and the only time I don’t have a cigarette is when I’m onstage. So perhaps nicotine withdrawal plays a part in the wildness.

Malcolm, do you ever get bored standing in back of the stage all night?

Malcolm: No. I love planting myself next to the drums and getting that groove thing going. I even put one of my feet against the drum riser so that I can feel the drums vibrating. Besides, Angus and Brian are the showmen—as was Bon—and they provide more than enough visual excitement. And it’s a good idea to stay out of their way because you can get run over!

Have you two ever had any serious arguments in the studio or in rehearsal?

Malcolm: We do have our “had enough” days. Particularly when the pressure is on, or if we’ve been working in the studio for a long time—you know, not sleeping and eating take-out food around the clock. But we’re not ones to stew for long. When we hear stories of what some bands go through—like Guns N’ Roses, for example—we think “Wow, what a waste.” Those guys should just grow up, get back together, and get back out there.

This interview first appeared in the July 2003 issue of Guitar Player. For more info on AC/DC, visit their website.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Whether he’s interviewing great guitarists for Guitar Player magazine or on his respected podcast, No Guitar Is Safe – “The guitar show where guitar heroes plug in” – Jude Gold has been a passionate guitar journalist since 2001, when he became a full-time Guitar Player staff editor. In 2012, Jude became lead guitarist for iconic rock band Jefferson Starship, yet still has, in his role as Los Angeles Editor, continued to contribute regularly to all things Guitar Player. Watch Jude play guitar here.