“When I switched to guitar, I still had the piano in me, so I developed the two-handed tapping technique to play the guitar more like a piano”: Stanley Jordan on playing piano and guitar simultaneously, and the pitfalls of higher (and lower) frets

Speaking to GP in 2008, the maestro discusses the particulars of his signature Vigier guitars, and how they avoid the tonal drawbacks one might encounter when two-hand tapping on other models

This interview was originally published in the June 2008 issue of Guitar Player.

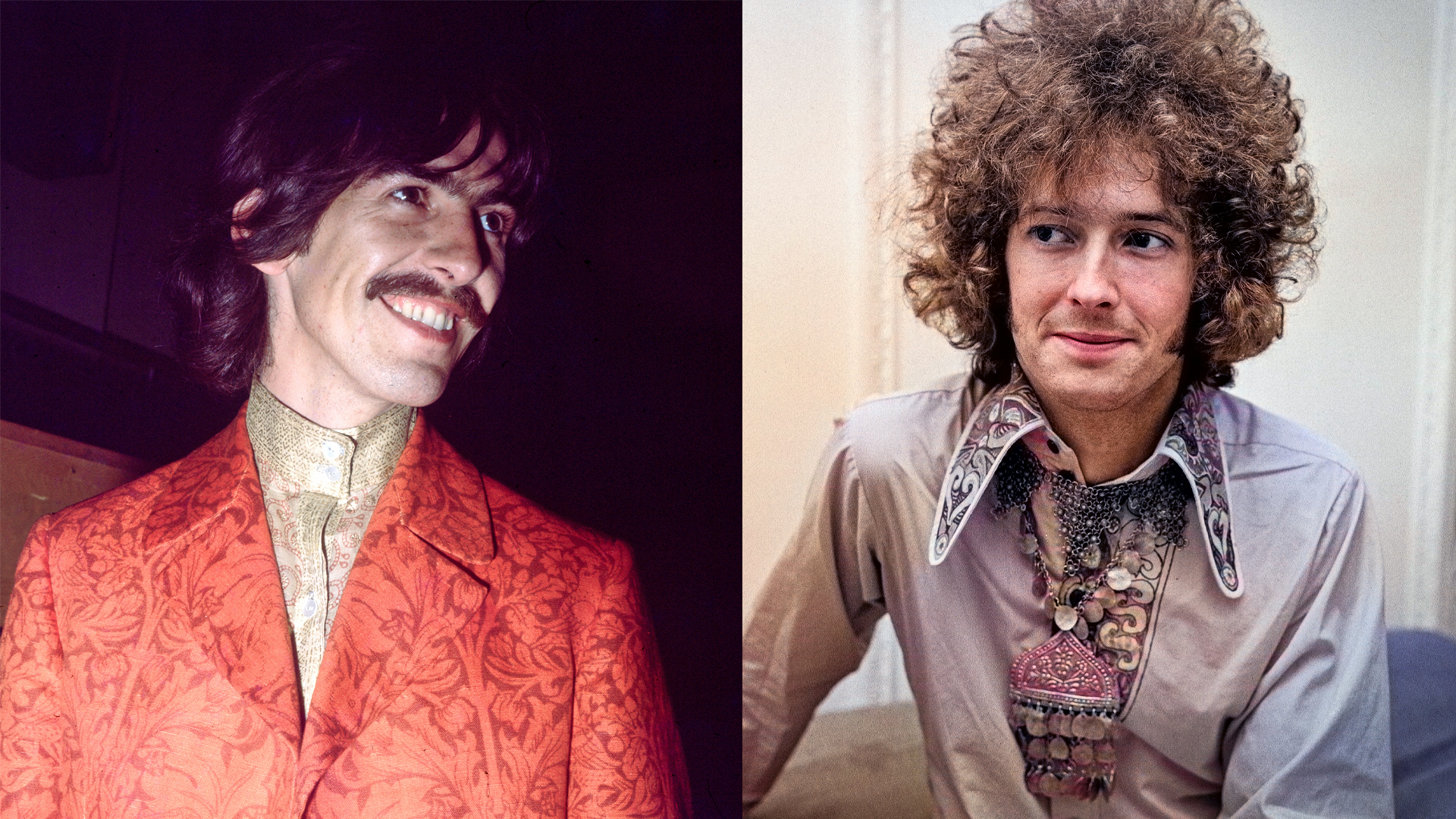

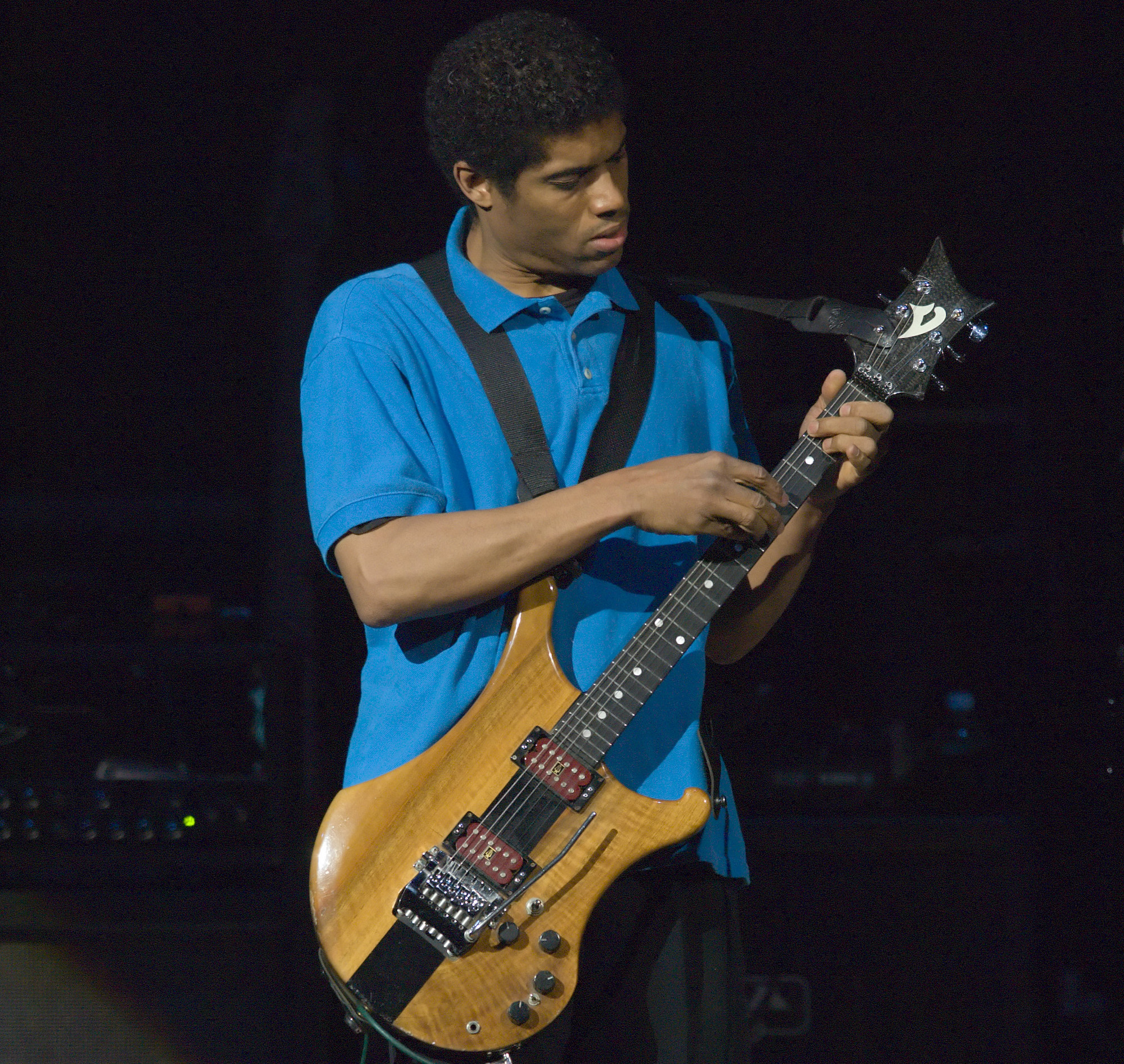

Shoppers on Manhattan’s Music Store Row in 1984 often found themselves awestruck by a young man playing on the street. Eddie Van Halen’s solo style had already hipped the masses to tapping techniques, but Stanley Jordan was comping harmonically complex jazz chords with his left hand, while playing lightning-speed, bebop inflected solos with his right.

Two decades into his career, we tend to take this amazing player for granted, but Jordan’s new State of Nature album should change that, as he ups the ante by playing guitar and piano at the same time.

“My original instrument was piano, and when I switched to guitar, I still had this piano thing in me, so I developed the whole two-handed tapping technique in order to play the guitar more like a piano,” explains Jordan. “When I did this album, I decided there was still a part of my music that lives in the piano. Fortunately, all the two-handed guitar playing I did helped me to keep my piano chops up [laughs].”

On the jazz chestnuts All Blues and Song for My Father, Jordan comps left-handed guitar chords while soloing on the piano with his right, and then switches to playing piano chords with the left hand while tapping guitar solos with his right.

“I am thinking of them together like a single instrument,” he says. “If you were using two hands on the guitar, or two hands on the piano, you would think of what you were doing as playing one instrument. I’m just applying that same kind of thinking to guitar and piano together.”

This time around, the guitarist also sometimes eschews his signature style altogether.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I had been playing with a pick for six years before I started playing with two hands on the neck,” says Jordan. “When I started using the piano on my album, I felt that I didn’t have to play the guitar like a piano all the time. I could play the guitar like a guitar.

“There is a place in the middle of All Blues where I started playing the guitar with my thumb – influenced by Wes Montgomery – which felt good, because I used to do that all the time. And I played all of Ocean Breeze on an Ibanez LR10 using a pick.”

Flat frets can be useful for funky pops, but you lose a lot of sustain when playing hammer-ons, so I recommend rounder frets

At other times – like for the distortion-heavy soloing on Shadow Dance – Jordan employed a hybrid style.

“On that tune, I played with my fingers, using a combination of plucking and tapping,” he says. “I did a lot of plucking rather than using a pick, because I wanted to get an edgier kind of sound.”

Jordan’s singing tone on the song is courtesy of an overdriven Matchless amp, and he got bluesy bends by tapping and bending. “But when you do that, you have to tap first, and then bend the string,” he cautions.

Jordan favors French-made Vigier guitars for tapping – and the unique, almost acoustic tone on Prayer For the Sea came from playing two of them simultaneously.

“My main Vigier has a solid and ringing sound, while the other one has more of a woody sound,” he says. (Jordan also played the woody sounding Vigier on Andante From Mozart’s Piano Concerto #21.)

Jordan’s preferred tuning is E, A, D, G, C, F (low to high). “It simplifies the fretboard, and because tapping with two hands is a complicated arrangement, anything that simplifies things helps,” he says.

The two-hand technique requires careful attention to the instrument’s set-up, and the wear on Jordan’s main Vigier made recording a challenge.

“The high notes were not coming through enough, and I was banging, which was hurting my hand,” he says.

“One of the problems a lot of guitars have when played with the two-handed technique is that the low strings overpower the high ones unless the instrument is set up correctly. The shape of the frets also has a big effect. Flat frets can be useful for funky pops, but you lose a lot of sustain when playing hammer-ons, so I recommend rounder frets. Also, harder frets produce louder sounds and impart additional high end. They don’t sound as warm as softer frets.

“Fret height can also affect intonation. You control the dynamics with how hard you tap, and tapping harder actually bends the string slightly. If you go for a triple forte, and you have really high frets, you are going to bend the note up. That’s normal with this technique – the louder notes tend to have a higher pitch. But if the frets are too high, it's too noticeable, which results in intonation problems. Conversely, if the frets are too low, you don’t have enough mass to get good tone and sustain.”

For most of us, playing simultaneous rhythm and lead guitar, guitar and piano together, or two guitars at once, would take up every spare brain cell – but that is all just the beginning for Jordan. The Princeton grad/math whiz/computer programmer’s latest obsession is music therapy.

“Music is a kind of philosophy, because it is a path of inquiry to help us understand the world,” he suggests. “Pay attention to all the little lessons you learn in creating music, because they are metaphors for life.”