“A lot of guitarists don’t consider themselves part of the rhythm section. I could always count on Randy to come up with great rhythm guitar parts”: Rudy Sarzo on the magic of Randy Rhoads' rhythm work, and the tonal quirks that set him apart

Rhoads' former bandmate details how the late guitar legend's rig changed over time, and what about his playing often gets overlooked

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The following interview with Rudy Sarzo was originally published in the December 2009 issue of Guitar Player.

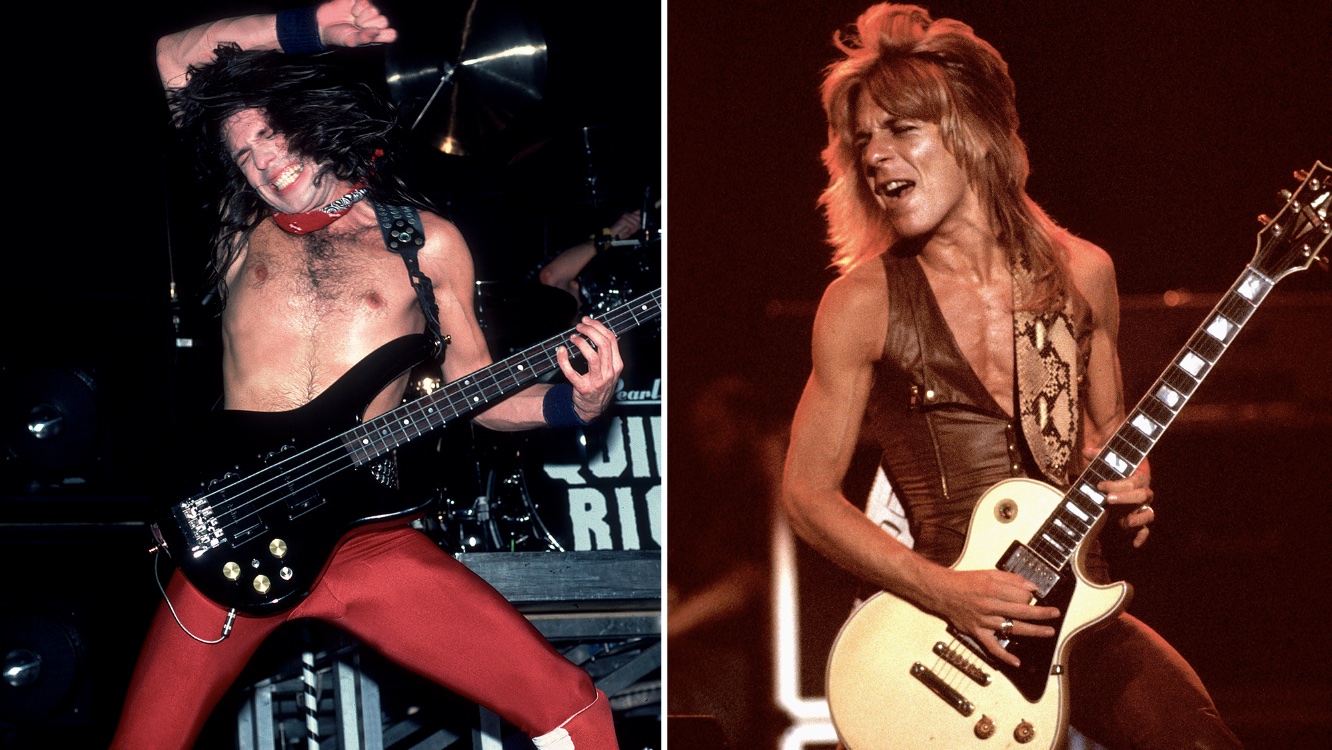

Although he’s played with lots of great guitarists, bassist Rudy Sarzo still gets the most questions about what it was like to play with the late Randy Rhoads.

“That’s why I wrote the book,” says Sarzo, referring to Off the Rails, a fascinating glimpse into his time with Rhoads. He spoke to GP about that time, now nearly 30 years ago.

You wrote that when you auditioned for Ozzy, Randy’s tone and his playing had changed a lot since your Quiet Riot days.

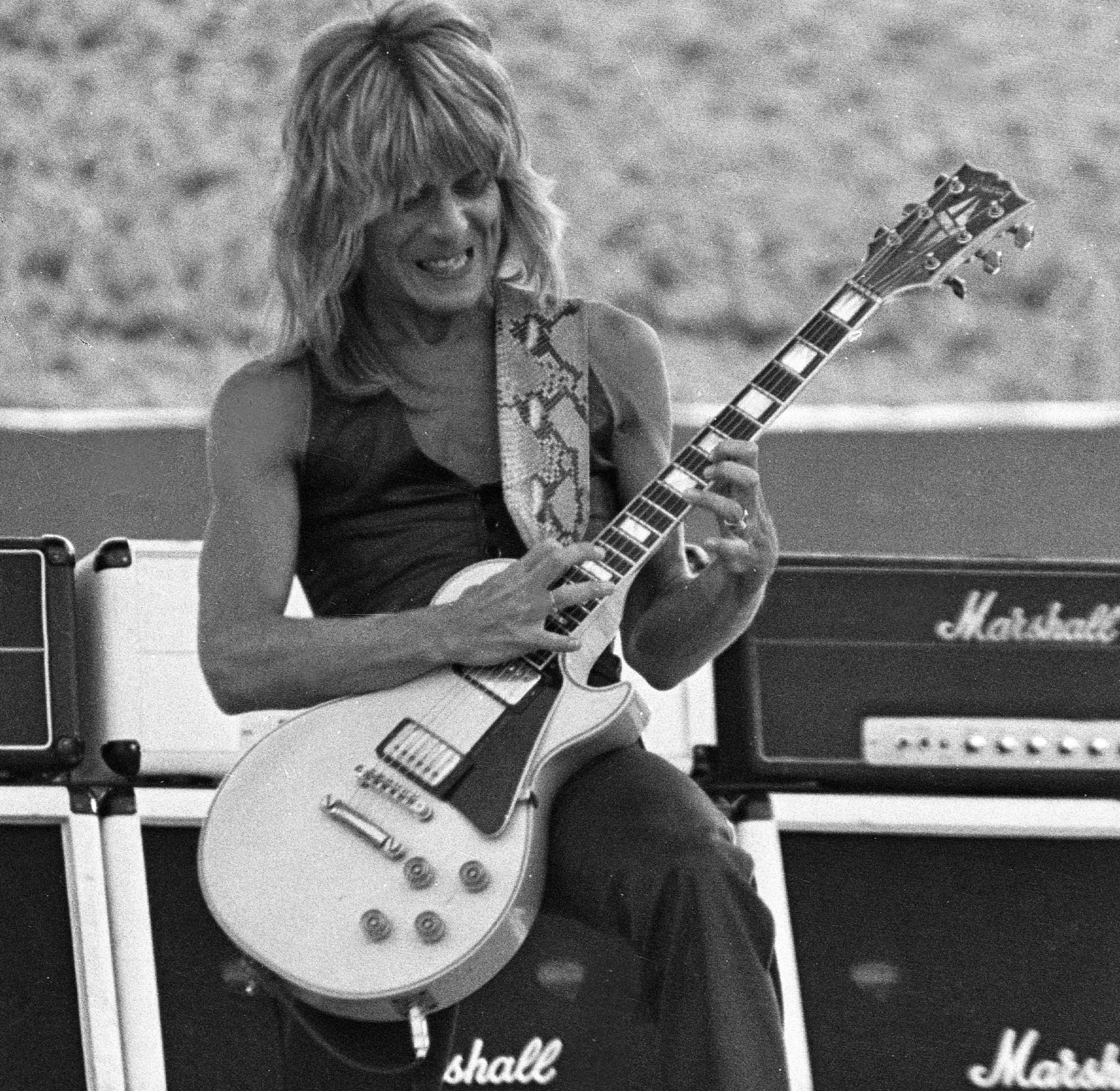

“His tone had totally changed. With Quiet Riot, he had a Peavey amp – it was some late-’70s solid-state model – and he had a cabinet with six JBLs. He ran his MXR distortion box in the front. With Ozzy he was using Marshalls, but to me one of the most important parts of his sound was the wah.

“He would keep the wah-wah on during his rhythm lines. I think he started using the wah with his Marshalls because they were giving him a wider tone than the Peavey. He wanted to cut down those lower frequencies. His tone was more shelved than the average guitar player’s. He specifically chose the right frequencies to make his rhythms sound articulate.”

His style was obviously totally different with Ozzy.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Well, you’re only as good or as eclectic as the songs on your list. When he was composing for Ozzy, Randy could go from Revelation Mother Earth to Flying High Again to No Bone Movies.

“Remember, when Randy got together with Ozzy, the ’80s hadn’t been invented yet as we know them. Record companies and MTV hadn’t started dictating what you could and could not play. I called producers ‘reducers’ because they were going with these very narrow ideas of what a rock song could be.

A lot of guitarists don’t consider themselves part of the rhythm section. With Randy, I could always count on him to come up with great rhythm guitar parts

“When a band had some success, they replicated that sound for the rest of their career and that became the formula for ’80s bands. Randy wrote his best stuff before all that and so he had a lot of freedom.”

What else can you say about his playing?

“The first thing I noticed about him was he listened. A lot of guitarists don’t consider themselves part of the rhythm section. With Randy, I could always count on him to come up with great rhythm guitar parts. He always listened to the drums and locked in. That really came together when he started playing with Tommy Aldridge.

“Tommy had played a lot of arenas with Pat Travers and Black Oak Arkansas, and he’s got a tendency to lean forward, which doesn’t mean that you’re rushing, but you’re on top of the beat in a real driving way.

“Randy naturally leaned forward in his timing too. That was one of the things that gave Quiet Riot an arena sound even when we were playing in clubs. He played big. He projected.”

Randy mentioned some players that he admired, like Michael Schenker, Gary Moore, and Leslie West. Who else did he talk about?

“Mick Ronson. If you listen to the end of You Can’t Kill Rock and Roll, it’s basically an homage to Mick Ronson’s playing on the Bowie tune Moonage Daydream.”

Footage of Randy shortly before he passed makes it seem like he had already gotten a lot better than even what was on the recordings.

“Yeah, I can totally vouch for that. He never stopped studying and trying to get better. That’s what he lived for.”