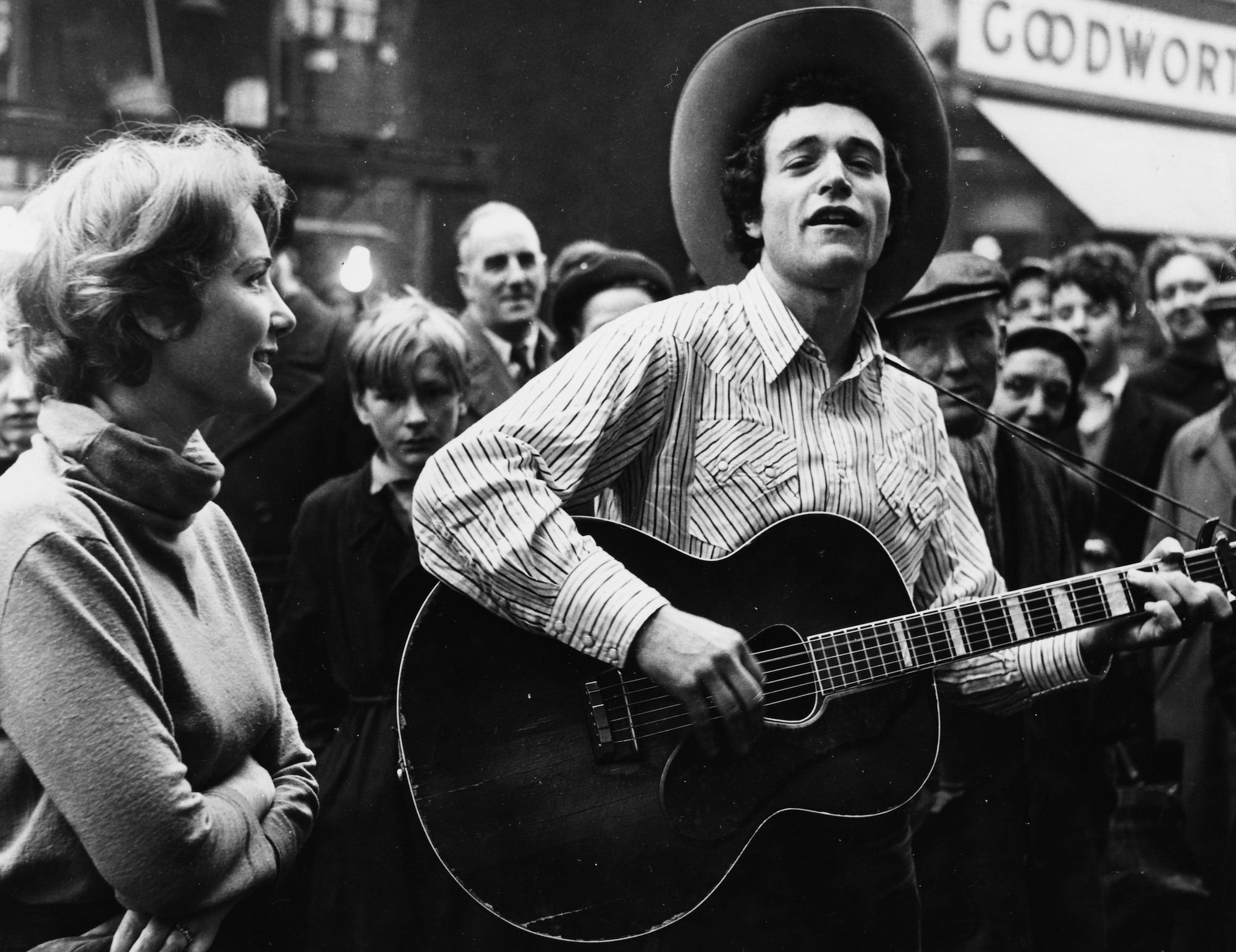

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott Reflects on His Friendship with Woody Guthrie and Why Bob Dylan's Act Made Him Stop Playing Harmonica Onstage

Now 91 years old, the man Dylan called “the king of folk singers" tells stories of his time with Jack Kerouac and James Dean, and his experiences touring with Dylan's Rolling Thunder Revue.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

His mentor was Woody Guthrie. His protégé was Bob Dylan. Between the two of them, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott has been the Johnny Appleseed of song, sowing the nation’s roots music in grounds both rural and urban. Although Dylan called him “the king of folk singers,” Elliott defies categorization and exemplifies genres such as cowboy, hillbilly, bluegrass, blues, and rock.

He has been equally comfortable performing with Pete Seeger, Tom Waits, Flea, and Beck. Homages flow from adherents such as the Rolling Stones, former members of the Grateful Dead, Bonnie Raitt, Eric Clapton, and Bruce Springsteen. Among his accolades are two Grammys and the Presidential National Medal of Arts. Johnny Cash observed of Elliott, “Nobody has covered more ground. He’s got a song and a friend for every mile behind him.”

That journey is the subject of A Texas Ramble, a recent documentary, and the earlier Ballad of Ramblin’ Jack, by his daughter Aiyana. The scope extends, quoting Guthrie’s anthem, “This Land Is Your Land,” which Elliott recorded, “from California to the New York Island/From the Redwood Forest to the Gulf Stream waters.”

Now 90 [Elliott has turned 91 since this interview was published in Guitar Player] this ultimate maverick long ago fulfilled the dreams he first wove in Brooklyn’s Flatbush neighborhood. “Brooklyn made me want to be a cowboy. I didn’t groove there very well,” he says.

“I always wanted to be out west in the wide-open spaces, riding horses, working cattle and singing ‘Red River Valley’ while picking my 12-dollar Collegiate guitar, made out of cigar boxwood. My mother bought it for me when I was 13, before I showed any interest, although I’d been listening to Gene Autry’s Melody Ranch.”

His wanderlust inspired by a friendship with a local Danish sailmaker, Elliott ran away from home with his friends, “future beatnik poets” Don Finkel and Carl Margolies, in April 1947, when he was 15. “We’d drink beer in a subterranean bar, near what became the Gaslight on MacDougal Street,” he says. “I suggested we hitchhike to Chicago to hear [trumpeter] Bunk Johnson’s jazz band.”

Along the way Elliott made a detour and, while passing through Washington, D.C., took a job grooming saddle horses with Jim Eskew’s Ranch Rodeo and Wild West Show. “I’d sleep in a tent with 60 horses three feet from their hind feet,” he says. “I was in heaven. We had a rodeo clown, Brahmer Rogers, who played hillbilly songs on guitar and banjo. I played some banjo but never got good at it.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Three months later he was back home, but, perhaps stirred by his time on the road, Elliott’s passion for the guitar began to flourish. His old Collegiate emerged from the closet.

“I’d bring it to school and played for my fellow students on the front stoop, singing cowboy songs,” he recalls. “Some kids even clapped.” Roy Acuff was his first singing influence, followed by Gene Autry, the Louvin Brothers, the Blue Sky Boys, and Lonnie Johnson, whom Elliott would eventually meet at Gerde’s Folk City in the Village in 1961.

During the summers of 1947 and 1948, Elliott played in Washington Square Park with budding folk artists Tom Paley, Erik Darling, Harry Smith, Roger Sprung, and Fred Gerlach. “Fred played Lead Belly songs on a 12-string guitar,” he recalls. “His girlfriend was Tiny Ledbetter, Lead Belly’s niece.”

A turning point came in 1951 when Elliott met his kindred spirit, Woody Guthrie. “Paley gave me his phone number,” he says. Guthrie invited him over before calling it off. “He said, ‘Don’t come today. I got a bellyache.’ It turned out he had a ruptured appendix. He went right in the hospital. The first time I met him he was lying in bed. I visited Woody there two days running.”

By this point Elliott had acquired a slightly shopworn Gretsch guitar for $75 from a music store on lower Third Avenue. He took the guitar with him to visit Guthrie and again soon after when he and a school chum made a trek to California in the friend’s Plymouth Coupe. In California, he met then-aspiring actor James Dean, the ex-boyfriend of Elliott’s bride-to-be, June.

“Something about Dean reminded me of Woody,” he says. “Strumming along on guitar, I improvised a song, just part of our conversation. Thoughts and feelings came out about Woody being sick in the hospital. I couldn’t remember it five minutes later. Even now, I don’t remember how the words were or sounded. It was a moment in history.”

Three months later, Elliott was back in New York City and performing under the name Buck Elliott. He reconnected with Guthrie at a party in the Village. “When I arrived, Woody was in an upstairs closet tuning his guitar and warming up,” he says. “He had his harmonica. They made requests. He charged five cents per, like a human jukebox. Somebody requested, ‘Blue Tail Fly.’ He said, ‘That’s a Burl Ives song. I get 15 cents extry for playing Burl.’

“Woody was playing a small-size Gibson. He was so proud owning that. He always teased me about the piece of junk my Gretsch was. Woody was hard on guitars. He’d been through several previous guitars that were full of holes, wrecked, cracked, and bent.”

Elliott lived with Guthrie from 1951 to 1953, but performed with him only once, as a guest at a concert in Newark. “I wasn’t known yet,” he explains, “just Woody’s sidekick.” Elliott would eventually come into his own, but he needed to do some living. It happened soon enough.

“In 1953, I met Jack Kerouac, a friend of my girlfriend at the time,” he says. “He’d come to her apartment and read to us his manuscript of On the Road. Over three days sitting on the floor and drinking six big bottles of red wine, we all took turns reading from it. That stirred my desire to hit the road myself.”

That summer he and a pair of friends and fellow musicians, Frank Hamilton and Guy Carawan, traveled by car from New York City to New Orleans, with his Gretsch in tow. “We performed on street corners. Farmers would take their hats off, shaking each other down, and collect money for us,” he recalls.

“We were meeting real hillbillies, sometimes sleeping overnight in their homes up in the Smoky Mountains. Frank was 17 and played banjo like a wizard. He later started the Old Town School of Folk Music in Chicago where they teach five-string banjo and guitar picking. Guy, who owned the car, was 21. He was a passionate singer who later introduced ‘We Shall Overcome.’”

By the time he returned to New York City, Elliott had matured into a solid performer. “Jack sounds more like me than I do,” Guthrie once declared. Although Elliott developed his own rugged strumming and picking style and plaintive approach to song, he remained a champion for his mentor and his music.

In 1961, Elliott would meet a fellow disciple 10 years his junior. “I had just gotten back from touring in Europe for six years with banjo master Derroll Adams,” he says. “I took a bus to visit Woody at Greystone Park Hospital in New Jersey. Woody was devastatingly sick and could barely speak. There was this strange kid from Minnesota visiting him. He introduced himself to me as Bob Dylan.”

Just 19, Dylan had moved to New York City in January 1961, intent on meeting Guthrie and launching his career in the Greenwich Village folk scene.

“I had about five records out on the English label Topic,” Elliott recalls. “He told me he had all of them and mentioned those he liked best.” Elliott’s influence on the young folk singer was evident to those who saw his early shows. “The first time I heard him perform, people in the audience poked me saying, ‘He’s doing your stuff. He sounds just like you,’” Elliott says. “He sounded good, but I didn’t think he sounded like me at all.

"I appeared with Bob at Gerde’s Folk City in the Village. They put up a piece of cardboard and somebody wrote, ‘Now Appearing: Son of Jack Elliott.’ I suppose I was a father figure to him. We played guitar and harmonica like little Woody clones.”

Like Guthrie, both men racked their harmonicas in metal braces hung around their necks. “Bob would always leave his in the upward position,” Elliott says, whereas he allowed his to rest on his chest behind his guitar, where the sharp metal would invariably come into contact with his guitar and scratch off the varnish.

Elliott says he grew weary of the whole enterprise. “I said, ‘We sound like the Harmonica Brothers, and anyway I’m tired of scratching my guitar, so I’m gonna quit playing. Have at it, Bobby!’ That’s when I officially stopped playing harmonica in my shows in order to get rid of that copycat element.”

When Dylan made his controversial shift to electric guitar in 1965, the folk community was appalled. Pete Seeger had witnessed the singer’s electric debut at the Newport Folk Festival that year and had to be restrained from severing Dylan’s guitar cable with a hatchet.

“My reaction wasn’t as strong as Pete Seeger’s,” Elliott notes. “But I could never put it into words. The new music was so different from his previous music, and I’m always shocked by anything electric. I’m not into electric gadgets, although I admire some of it. I never had an electric guitar. I never learned the real art of playing electric.” Ironically, he did play electric for Dylan.

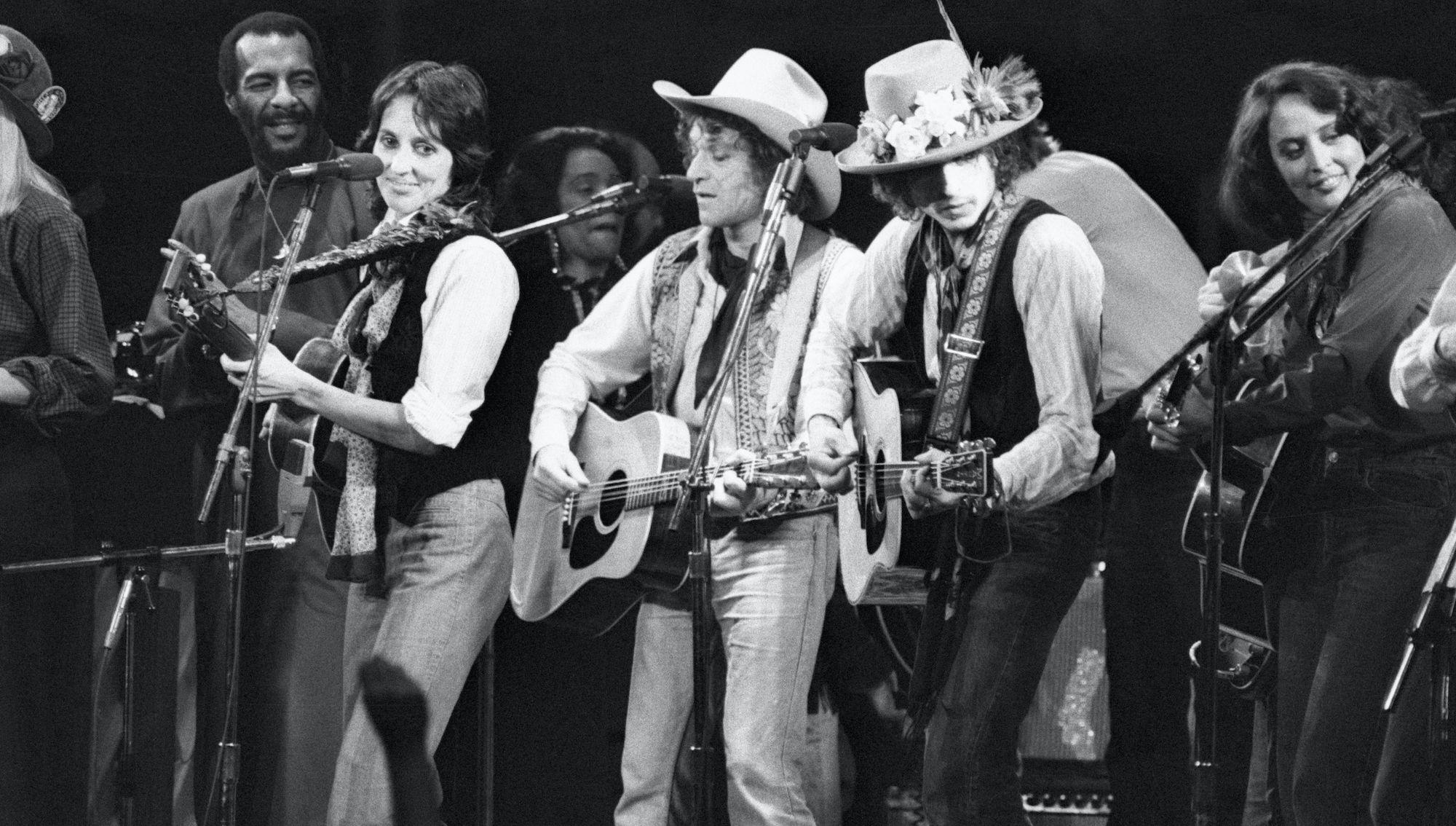

In 1975, Dylan saw Elliott perform at the Other End – then the temporary operating name of New York City’s famed Bitter End folk club – and invited him to join his plan for the Rolling Thunder Revue. “He spoke about his idea of a bus tour of small venues around the country with him, Joan Baez, Bobby Neuwirth, and myself,” Elliott recalls. “Patti Smith was there. Bob, Patti, Bobby, and I got up on the stage and sang.”

A few months later, Elliott was performing at the venue again when Neuwirth showed up. “Neuwirth came to the gig and then called Bob in California,” he says. “Neuwirth handed me the phone. Bob said, ‘We’re gonna do the tour in November starting in New York City.’ I said, ‘Okay.’ Bang! Those eight seconds is how the tour began.”

For the stint, Elliott borrowed a Fender Telecaster from fellow performer T-Bone Burnett. “I played two songs on it with the band, one of which was Jesse Fuller’s ‘San Francisco Bay Blues,’” Elliott says. “I usually play that as an opener to get warmed up."

The Revue also saw Elliott perform in Dylan’s 1978 film Renaldo and Clara, which he filmed prior to and during the tour. “It’s a collection of Revue performers,” Ellott explains. “With a cameraman, Bob shot 200 hours of 35-millimeter Technicolor film. Sam Shepard wrote the script. I had fun as a would-be actor in mysterious and dense little dramatic scenes.”

Elliott has formed many other musical friendships over his long career, including with Todd Snider, the late John Prine, and Johnny Cash.

“I looked up to Johnny Cash. Of course, I was only five-eight and he was six-eight, so I had no choice,” Elliott jokes. “But he was a fine friend.” Although they performed together only once – a rendition of Cash’s “Take Me Home” on his ABC series, The Johnny Cash Show, in 1969 – Cash recorded Elliott’s song “A Cup of Coffee” on his 1966 album Everybody Loves a Nut.

Once, while visiting Kris Kristofferson and Rita Coolidge at a Hollywood recording studio, Elliott was surprised to discover a small trio of famous players in the room.

“Kris said, ‘There’s someone who loves you in Studio A,’” Elliott relates. “There were two gentlemen playing guitar when I got there: I recognized David Bromberg. The other guy was a Beatle, whom I didn’t recognize. It turned out to be George Harrison. I looked around to see if I could recognize anybody else. There was Ringo, winking at me. I winked back. I thought, Well, that’s cool.”

From 2002 to 2006, Elliott joined Odetta and Josh White Jr. for the Glory Bound tour, honoring White’s father, Lead Belly, and Woody Guthrie. “Odetta’s mother gave me the name Ramblin’ in 1954,” he reveals. He comes by the name honestly. Despite an extensive discography, Elliott prefers being on the road and performing live to audiences. “I like the spontaneity,” he says simply.

These days he plays a D’Angelico acoustic gifted to him by Bob Weir. “I had been playing a Martin D-28, a lovely guitar with a beautiful tone,” he explains. “But it’s big. Now I got arthritis in the shoulder from having to hold up my elbow parallel with the ground. I can’t hold that guitar anymore.”

He’s had other age-related issues to deal with. Last summer, Elliott celebrated his 90th birthday, an event that was intended to go down with a bang.

“Originally, the entire Guthrie family was going to host it at the Guthrie Center in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, on August 1, at the end of my first post-pandemic tour,” he says. “But I had a little hospital episode that wasn’t serious but managed to collapse the tour. Consequently, I lost my birthday party at the Center.”

Elliott has since recovered and been on the road, playing in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, and California. He recently performed his music with actor Robert Carradine at a gala Beverly Hills celebration of Jack Kerouac’s centennial. And on June 26, Arlo Guthrie’s daughter Sarah Lee performed with him at the 25th edition of the Kate Wolf Festival.

“There’s a lot of Woody in her,” he says of his mentor’s granddaughter. “Once, I was admiring the pond on Arlo’s farm. Little Sarah growled, ‘You shouldn’t swim in that pond. There’s catfish in there.’ I thought it was Woody talking to me.”