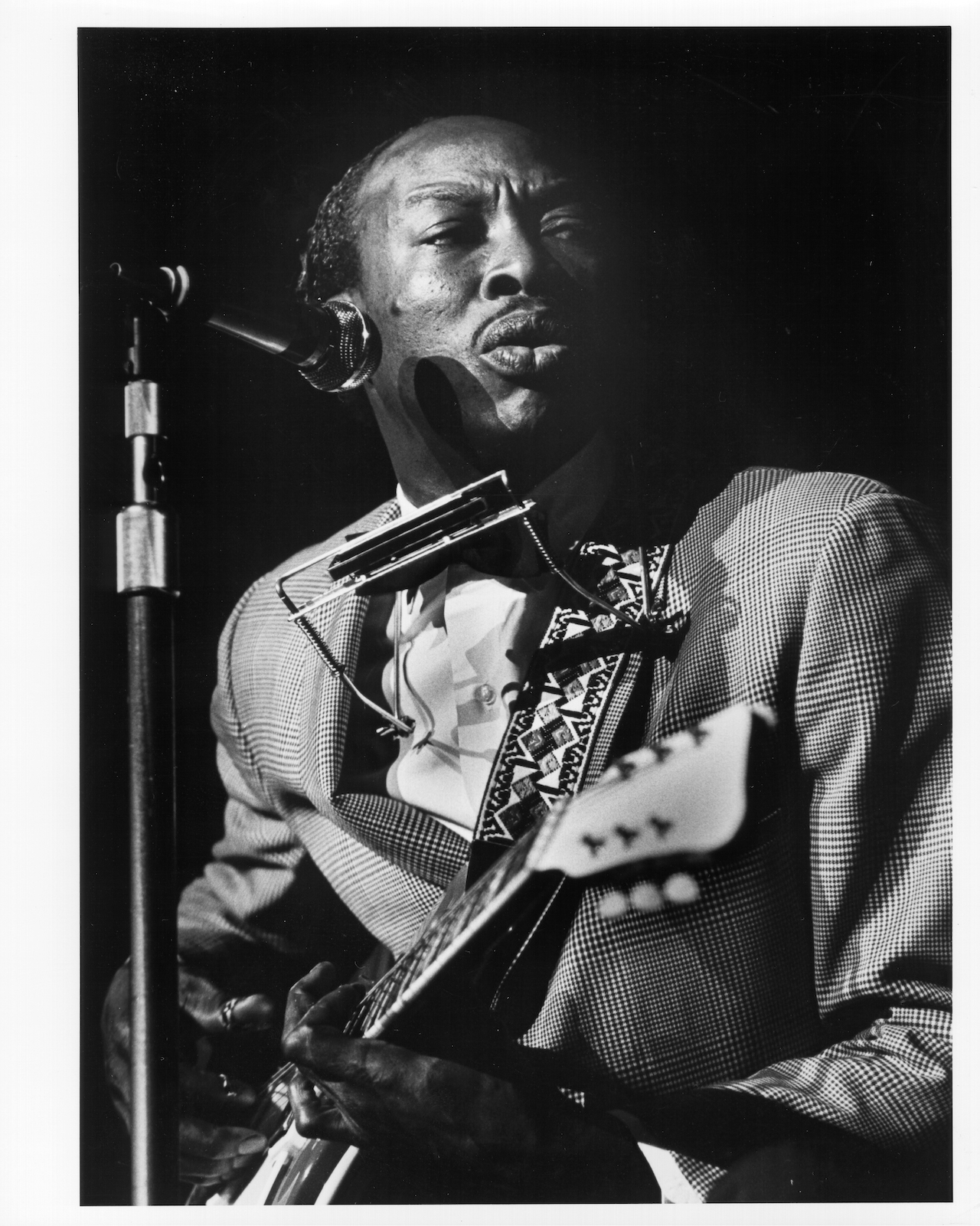

Elvis Presley and The Stones covered his songs, Albert King played drums in his band and Bob Dylan wrote a song about him. Two months before his death, Jimmy Reed told us his story in his own words

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

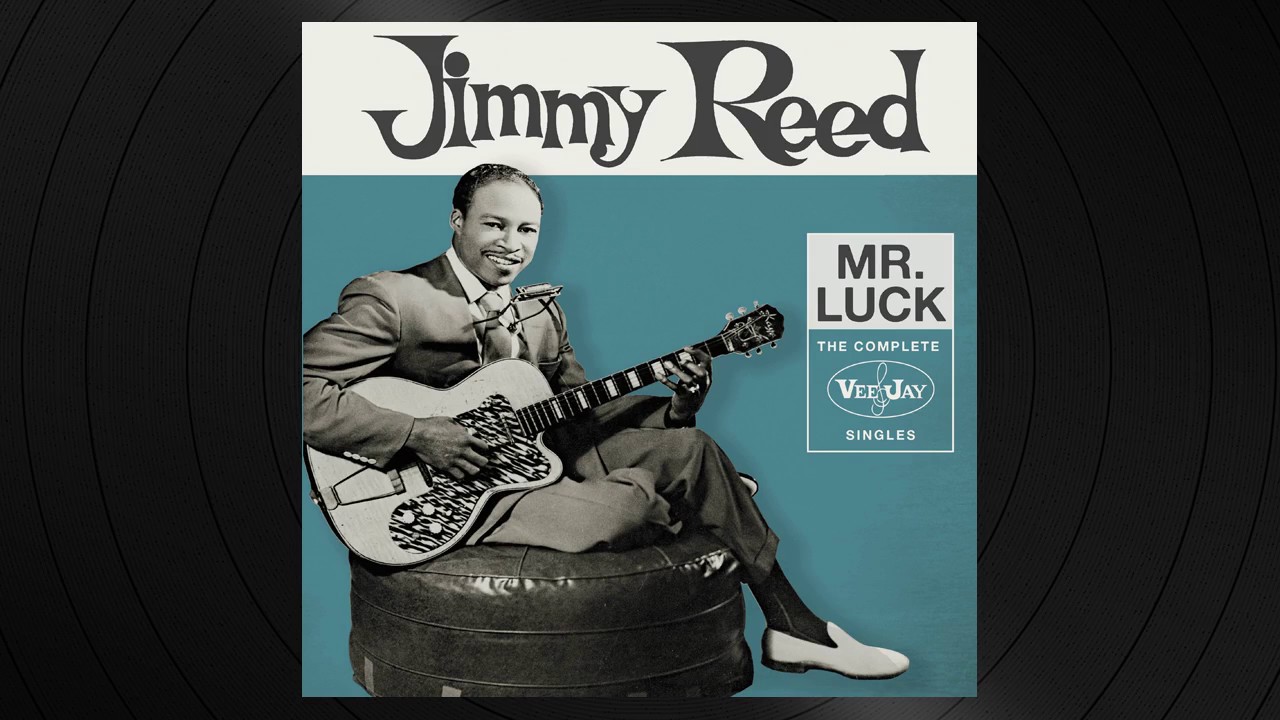

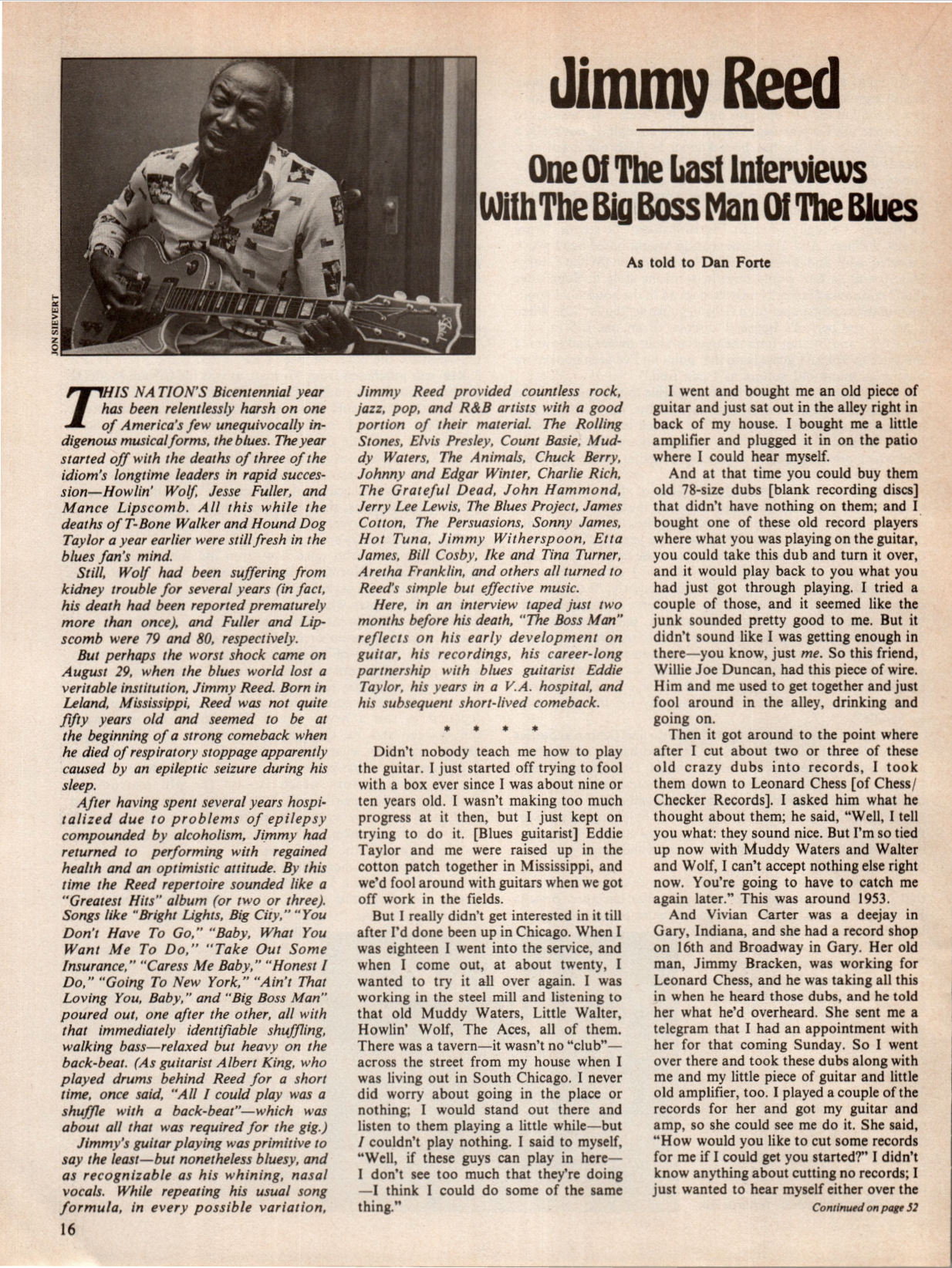

Jimmy Reed died on August 29, 1976, aged 50, leaving behind a repertoire that sounded like a Greatest Hits album – songs like 'Bright Lights, Big City', 'Baby, What You Want Me To Do', and 'Big Boss Man' – that were covered by artists like The Rolling Stones, Elvis Presley, Muddy Waters, The Animals, Van Morrison's Them, The Grateful Dead and many more.

Here, in an interview by GP's then-Assistant Editor Dan Forte, recorded just two months before his death and published a few months after, 'The Boss Man' reflects – in his own words – on his early development on guitar, his recordings, his career-long partnership with blues guitarist Eddie Taylor, his years in a V.A. hospital, and his subsequent short-lived comeback.

"Didn't nobody teach me how to play the guitar. I just started off trying to fool with a box ever since I was about nine or ten years old. I wasn't making too much progress at it then, but I just kept on trying to do it. [Blues guitarist] Eddie Taylor and me were raised up in the cotton patch together in Mississippi, and we'd fool around with guitars when we got off work in the fields.

"But I really didn't get interested in it till after I'd done been up in Chicago. When I was eighteen I went into the service, and when I come out, at about twenty, I wanted to try it all over again.

"I was working in the steel mill and listening to that old Muddy Waters, Little Walter, Howlin' Wolf, The Aces, all of them. There was a tavern — it wasn't no 'club'— across the street from my house when I was living out in South Chicago. I never did worry about going in the place or nothing; I would stand out there and listen to them playing a little while—but I couldn't play nothing.

"I said to myself, 'Well, if these guys can play in here— I don't see too much that they're doing — I think I could do some of the same thing'.

"I went and bought me an old piece of guitar and just sat out in the alley right in back of my house. I bought me a little amplifier and plugged it in on the patio where I could hear myself.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"And at that time you could buy them old 78-size dubs [blank recording discs] that didn't have nothing on them; and I bought one of these old record players where what you was playing on the guitar, you could take this dub and turn it over, and it would play back to you what you had just got through playing.

"I tried a couple of those, and it seemed like the junk sounded pretty good to me. But it didn't sound like I was getting enough in there — you know, just me. So this friend, Willie Joe Duncan, had this piece of wire. Him and me used to get together and just fool around in the alley, drinking and going on.

"Then it got around to the point where after I cut about two or three of these old crazy dubs into records, I took them down to Leonard Chess [of Chess/Checker Records]. I asked him what he thought about them. He said, 'Well, I tell you what: they sound nice. But I'm so tied up now with Muddy Waters and Walter and Wolf, I can't accept nothing else right now. You're going to have to catch me again later.'

"This was around 1953. Vivian Carter was a deejay in Gary, Indiana, and she had a record shop on 16th and Broadway in Gary. Her old man, Jimmy Bracken, was working for Leonard Chess, and he was taking all this in when he heard those dubs, and he told her what he'd overheard.

"She sent me a telegram that I had an appointment with her for that coming Sunday. So I went over there and took these dubs along with me and my little piece of guitar and little old amplifier, too. I played a couple of the records for her and got my guitar and amp, so she could see me do it.

"She said, 'How would you like to cut some records for me if I could get you started?' I didn't know anything about cutting no records, I just wanted to hear myself either over the radio or in the jukebox.

"So we arranged to do a session, but I didn't have no band. She said she'd get the musicians to play behind me and asked me if I wanted pianos or horns or what in there. I never did bother about having piano on no records – it just didn't sound right to me. At the speed of the background I had, it seemed like it was always betwixt and between — wasn't fast enough or slow enough either."

"And when I got to the studio the next week, she had Eddie Taylor there to play background behind me! So on some of them records there was him, me, [guitarist] Lefty Bates, a drummer — and my son [Jimmy "Boonie" Reed Jr.] had been fooling with my guitar and got pretty good himself.

"So I had something like four guitars, and the drums made five, and I was blowing harmonica, too, just like I do it now. The one that made me want to get a harmonica was old man Sonny Boy Williamson—the original [John Lee Williamson], the one that did "Good Morning Little Schoolgirl." He could play some stuff! I was fooling with it in Mississippi and started playing with a harness in about '52.

"So we did the session, and it sounded pretty good. The first record was 'Found

My Baby Gone'. They named the company Vee Jay — 'V' for Vivian and 'J' for Jimmy Bracken. Their first records was mine. When I first started making records I thought everything was going to be all right. And everything was all right until the thing started making money. I was supposed to be getting royalties, but I didn't get none.

"But I been thinking about cutting some more records, and a lot of people have been on me to do some more. But anyway, back in 1954 Vee Jay put out this thing I had cut about 'You Don't Have To Go' with 'Boogie In The Dark', a stone instrumental, on the reverse side.

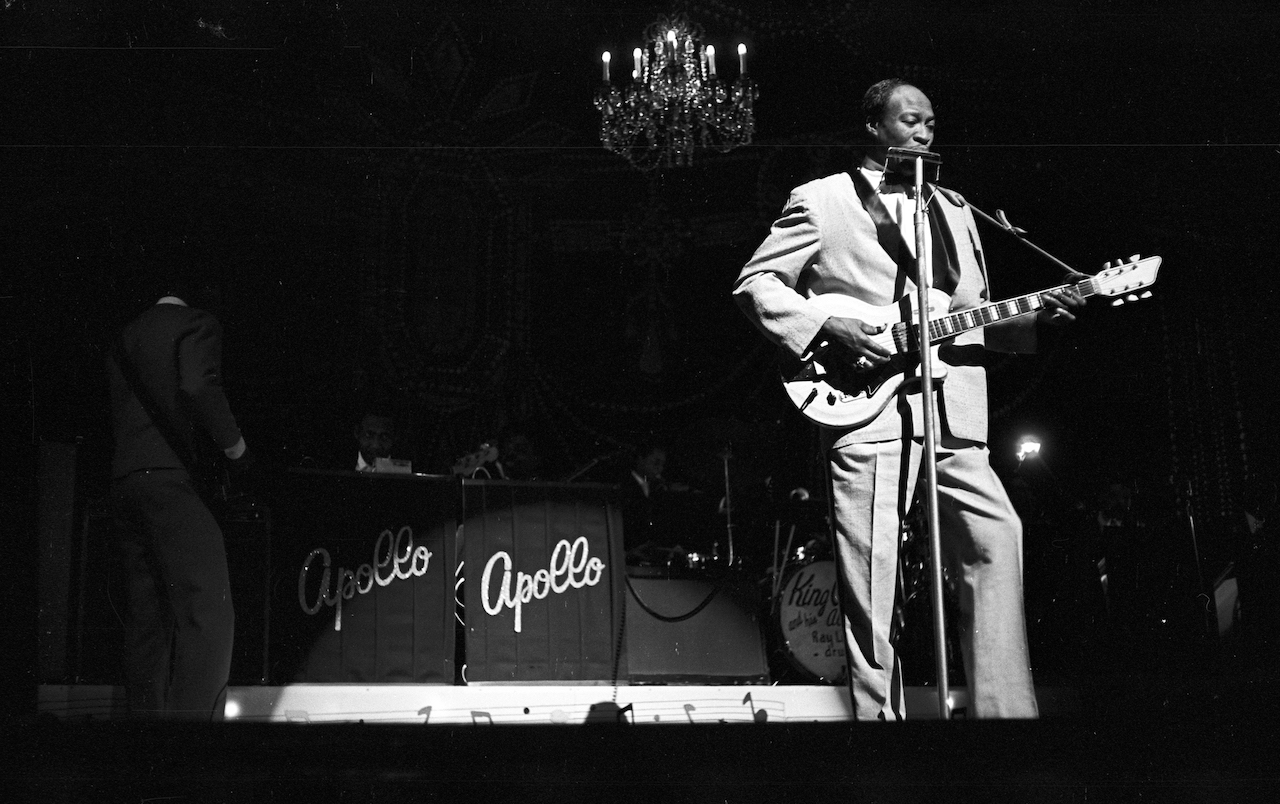

"One evening I was coming home from the Armour Packing Company — I'd quit the iron foundry and was working as a butcher — and I heard this old number 'You Don't Have To Go' over the air.

"The guy on the radio said, 'That's Jimmy Reed. He's going to be out in Atlanta, Georgia, this Friday and Saturday night' — and this was Thursday evening! I didn't know that I was booked in Atlanta. I headed home, grabbed my junk, headed to the studio to cut a couple of numbers, and told Eddie Taylor: 'Eddie, I'm supposed to be in Atlanta, Georgia – you going down there with me?' He said, 'Yeah, wherever you want to go!' So we bought a little jug and struck out driving to Atlanta. And I never did go back to the packing company to even give them back my knife or my clothes or to get my check or nothing.

"That was the first time I had went on the road or played anywhere before the public. I'd just been playing up and down the alley or at friends' houses. I went to see other guys in Chicago playing in clubs — go by just to holler at them. I didn't want to play or see the show either; I just wanted to speak to them.

"Muddy Waters, B.B. King, all of them big cats — 'Oh, you're Jimmy Reed? I'm so glad you come down here to see me. How much they charge you to come in?' 'Oh, they let me come in for nothing.' 'Well, come back in the dressing room.'

"And I'd go back and listen to them talking about this, that, and the other, but it didn't mean too much to me – I didn't know nothing. I was working one-nighters mostly in Texas, Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Georgia, and out on the West Coast— while I was still living in Chicago. I might be playing in California one night and have to be in Washington, D.C. practically the next night.

"I had a little stage fright about playing before the public, but I was drinking liquor at the time. I wasn't never no pot smoker, and I never did fool with any of that cocaine or junk or crazy pills, but I'd drink me some liquor.

"Then in the Sixties sometime, I started having these [epileptic] seizures. I remember one time I went on the stage, and I didn't even know when I came off. I must have collapsed on the stage, and they carried me off. After they found out I had been in the service, the V.A. hospital in Downey, Illinois accepted me in 1969.

"The doctor said my nerves had got shook up, and the liquor I was drinking just kept pushing me. He said he thought it would be good idea for me to quit playing music for a while, quit cutting records and everything.

"He said, 'You need to just lay down and rest a while; let your nerves get together.' Used to be I could feel those things coming on, and I'd go sit down. But then they started coming on me in my sleep; then I'd have a heck of a time. Because you're capable of coming out from under them things, and you're capable of not coming out.

"If there ain't nobody there to stick something in your mouth, you might swallow your tongue or something. Then I left the hospital and lived in one of these registration [convalescent] homes until the doctor said, 'Jimmy, you can go home when you get ready.' So they'd mail me a supply of medicine about once a month after I left in '72. I gave up music for about four or five years; I didn't cut no records or do nothing.

"I played guitar a lot in the hospital, though. They had a big old music center up there where I would go and get me a guitar and amplifier and just lock up in a room all day. And I didn't have nobody to help me out and back me up. See, during my first two or three records I wasn't doing nothing but blowing the solo on the harmonica and starting off the intro on the guitar. Then the rest of the band would haul off and head into it.

"But after I got in the hospital, my style changed in a way: I started trying to play my intro part, as much of the lead part as I could get in, do my singing part, blow the solo on the harmonica, and play the bass part all the way through, too. I started doing all that myself, which was a pretty hard thing. But it got me to the place where if I ain't playing the lead part, it don't sound right now, since I been doing it a few years.

"I used to do all my numbers with a Bb harmonica, which would cause the guitar to be in F. But after so long it started to strain my voice, so I started playing A harmonica which caused the guitar to be E. I put a clamp [capo] on the 5th fret when I blow on the high part of the harmonica, and the band will be playing in A then. Of course you don't have to put a clamp on it — there's a whole lot can be played up there without one."

"Eddie Taylor, he don't fool with a clamp. He's played with everybody, and you don't ever catch him putting a clamp on. I imagine if I hadn't tried to play the harmonica and done nothing but play guitar with everybody, I'd probably have been like him. Eddie, I don't care how many records he's made, or who he's played with, when he plays somewhere with me, he don't worry about playing nothing he ever did on anyone else's junk. He helped me on all my records but about two. I can't play behind anybody else. I have to start my own thing and let everybody push me.

"You can put me up there with somebody else playing, and I can't a bit more get in tune or keep up with them. But let me start my stuff, and I can go ahead on. My son also played on all my records, except the first couple and the last couple. He's a stone musician. I ain't nothing, but he can play music, write music, read music, arrange music — he's just long gone with it. But he can't sing worth nothing, and he don't like the blues. He's a rock and roll type. He learned the guitar just from being around me — I ain't taught him nothing.

"Sometimes I'd go down in the basement and be up all night, trying to see what I could play on the thing. He wasn't nothing but a little kid, and he'd sit down there with me till him and the dog would fall asleep in the corner. I think he was, I should say, ten or eleven years old when he first played on a record of mine.

"He plays rock and roll, but me, myself, I play the blues. I don't play no rock and roll stuff, but my records made it on the rock stations, because the background just had some kind of a beat to it that just got everybody to moving.

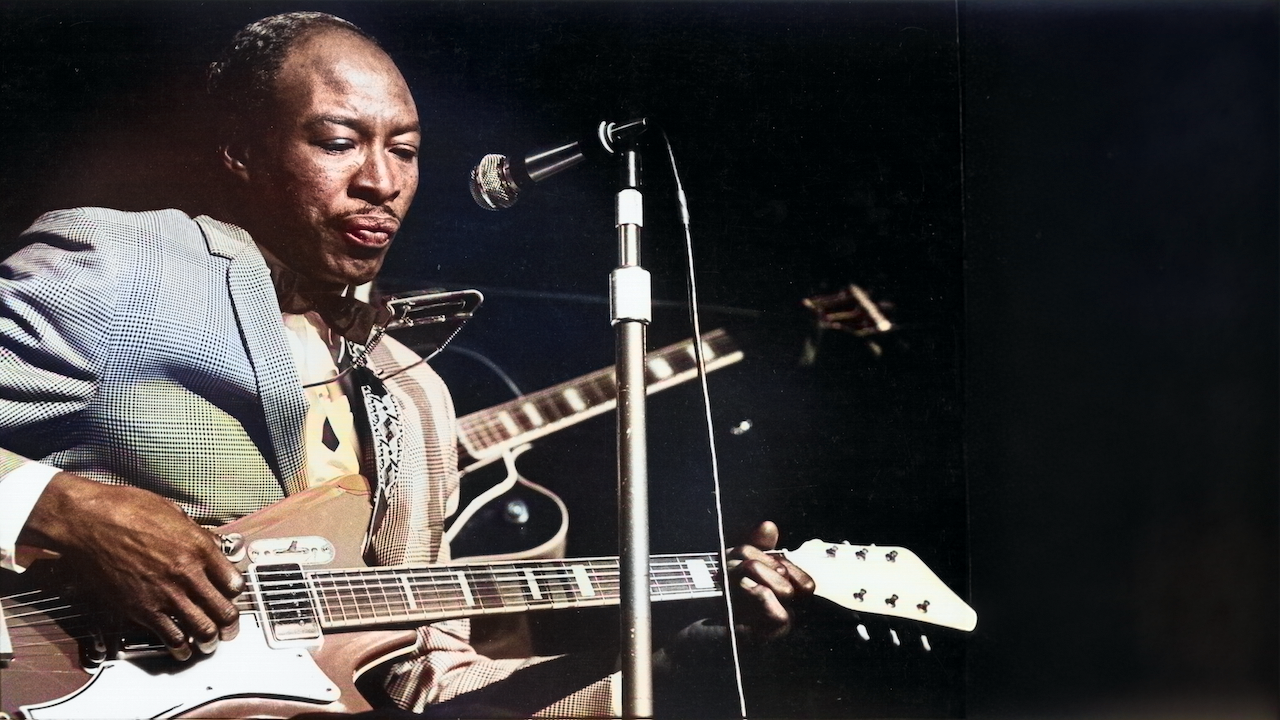

"When me and Eddie used to fool around in Mississippi, they wasn't making no electric guitars. I started off with one of those "folk" boxes with the hole in the middle. But when I got to recording I had me an electric. I played some of everything—I never did have no special brand. Then in '72, after I got out of the V.A. hospital, I was at a music shop getting some picks and strings, and I saw this guitar [a Japanese, Ariel, Les Paul copy]. It had the type of feel I like in a box. So the guy let me have it for $42 or $52— I thought it was a pretty good deal.

"My amp is an old Fender Concert; I think it was one of the first ones they made. I had a newer Fender amp, but I got this Concert for $90. I cut the reverb clean off; I put the bass at 5, the volume at about 4, and I just turn the guitar volume barely off 0.

"The average cats on the bandstand, they turn their box wide open and have them blasting. I don't call that music – you can't hear what the other guy's doing. I can see them doing that if they're reading everything off sheet music, but when you're just playing by ear, you have to listen to who's doing what.

"When I started out, I used a flat pick. But with the straight pick, in my style, the wrist will get tired. So then I started using the fingerpick and thumb pick, so there ain't nothing to get tired out but just my thumb. If I wanted to come off the bass with the lead notes, that's when the index finger comes in.

"This song I made about 'Big Boss Man', I've tried to show a lot of guys who was stone musicians, pretty well professionals, how to play the intro to that, and they can't do it so it sounds right. I just do my one straight thing. But it seems to work out pretty good like it is."

First published in Guitar Player, December 1976.

Dan Forte was Assistant Editor at Guitar Player 1976-1978 and then from 1983-1989, where he became Editor At Large and interviewed Stevie Ray Vaughan, Mark Knopfler and George Harrison among others. He later became Editor At Large at Guitar World and is currently Editor At Large at Vintage Guitar magazine.