“Allan Holdsworth is untouchable, unimpeachable... He is just the total king. I would build a shrine to him”: Meet Max Light, the jazz guitarist who loves John Coltrane, Miles Davis, and Meshuggah in equal measure

The Brooklyn-based virtuoso is unafraid to challenge himself – see his mind-boggling re-interpretation of Coltrane’s 26-2, and tunes so challenging he could only get through one take in the studio – but is nonetheless a “serial monogamist” when it comes to his beloved Collings

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

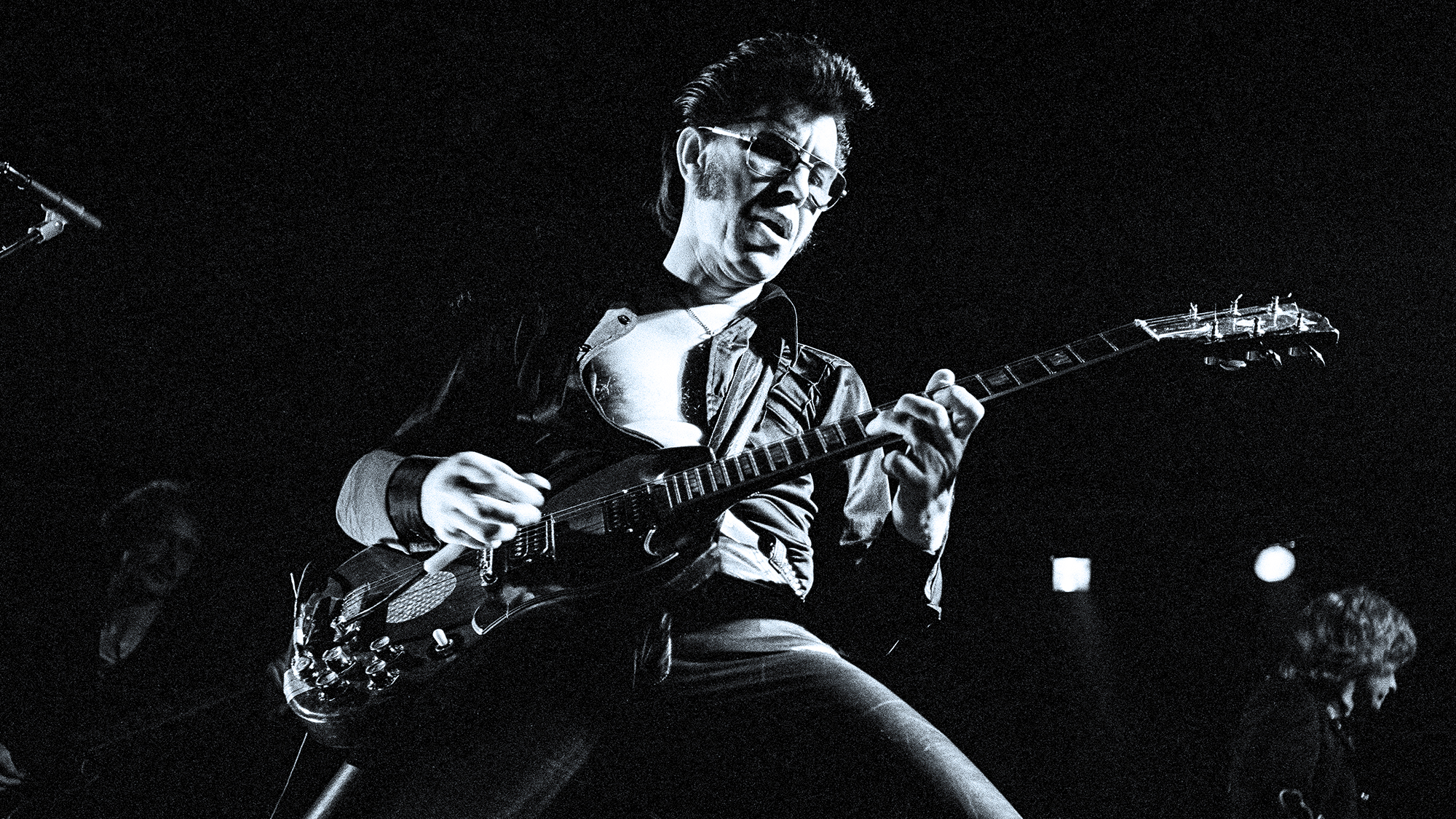

His name is like that of a Marvel superhero or the title character in a new vigilante series airing on Netflix. But Max Light plays guitar with the gift of one who has organically incorporated the lessons of his six-string forebears Kurt Rosenwinkel, Ben Monder and Allan Holdsworth into a singular vocabulary.

While his long fingers allow him to make uncommon stretches on the fretboard and conjure up near-impossible chord voicings à la Holdsworth and Monder, Light’s blazing legato runs and use of an Electro-Harmonix POG2 to eliminate his picking attack come straight out of the Rosenwinkel playbook. And he applies it all in a flawless and captivating manner on his two most recent recordings, 2023’s Henceforth, and his new album – and third as a leader – Chaotic Neutral.

Light grew up in Bethesda, Maryland, where, as a quintessential millennial, he played games like Dungeons and Dragons. He even named one frantically swinging Ornette Coleman–inspired piece on Henceforth after Luftrausers, an airborne dogfighting video game that served as the song’s impetus.

“I was playing the game and was really into the music of Ornette Coleman at the same time,” he explains. “The form itself is an eleven-and-a-half-bar blues, basically, but with all these harmonic substitutions. So it’s a bunch of different ideas mashed together.”

Such serendipity might only come from an outstanding player and facile improviser with a Brainiac-like thirst for knowledge – which is an accurate way to describe the 30-year-old Light. He sits comfortably alongside such gifted contemporaries as Julian Lage, Nir Felder, Gilad Hekselman, Matteo Mancuso, and fleet-fingered Aussies Josh Meader and Ben Eunson.

After graduating from the New England Conservatory of Music and placing second in the 2019 Herbie Hancock Institute of Jazz International Competition, he distinguished himself as a sideman in tenor saxophonist Noah Preminger’s band before releasing his debut as a leader with 2020’s trio recording Herplusme.

Henceforth features tenorist Preminger, bassist Kim Cass and drummer Dan Weiss, and finds Light revealing his love of dissonance and open-string playing on the title track, as well as an ongoing interest in West African rhythms on Barney & Sid (named for his girlfriend’s two cats, not for Kessel and Jacobs).

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

He also tackles some challenging unisons alongside Preminger on the knotty Subjective Object before settling into a calming, lyrical homage to Billy Strayhorn on Animals, which serves as well as a showcase for his beautiful voice leading.

But perhaps most mind-boggling of all on Henceforth is his cleverly titled Half Marathon, a rhythmic contrafact – a composition developed from a previous work – on John Coltrane’s 26-2.

As Light explains, “I was trying to challenge myself and come up with stuff to do during the pandemic, and I had this idea of the title being written with a division sign instead of a hyphen so that it becomes 26 ÷ 2, which would make the meter 13. And since a marathon is 26.2 miles long, that would also be 13 when divided in half. Hence, the title.”

While Henceforth continues the chemistry Light established playing in Preminger’s piano-less group, Chaotic Neutral features a new band with his Brooklyn colleagues Julian Shore on piano, Walter Stinson on bass, and Steven Crammer on drums.

“This is the first record where I was able to hire my best friends,” he explains. “These are the dudes that I hang out with in Brooklyn. We get together and drink beer and just talk about music, and I feel like that energy and camaraderie is very apparent in the way we play together.”

His tight rapport with Shore comes from having self-released their duo album in 2023, prior to a tour of Japan last year.

“Julian hit me up in April of 2023 to go on a duo tour with him in Japan that July,” he explains. “And about a month after he called me for it, he said the promoter over there wanted us to have a record to give to radio stations and clubs to promote our gigs.

“We had to make a record within a month, and I think it captured the moment – the excitement and fervor of that tour. I mean, here we were together in a country where we didn’t speak the language, playing all these gigs and trying to make it happen every night. But what made it easy is the fact that Julian is such an amazing listener.

“So it was a really interesting process getting in there and workshopping one-on-one with an amazing piano player like Julian,” he continues. “It just really opened my mind to all of these harmonic possibilities of the instrument – the ability to stack chords on top of chords on top of chords. And without even realizing it, that kind of thinking just worked its way directly into my own conception of music and my compositional process.”

On Chaotic Neutral, Light and Shore engage in some extremely challenging unisons on tunes like the title track and Pathos. The seamless manner in which they do so recalls the intricate, tight unisons and through-composed lines that alto saxophonist Lee Konitz played with Lennie Tristano, Warne Marsh, and Billy Bauer on his 1955 Prestige album, Subconscious-Lee.

“That music was immensely influential to me, and it still is,” Light says. “Lennie Tristano had the biggest impact on me. I transcribed a bunch of his solos from Tristano. Those lines are unbelievably beautiful and full of twists and turns and harmonic surprises. And Pathos is definitely coming directly out of that Konitz-Marsh-Tristano-Bauer scene. I love that music.”

Light’s tune Things, a contrafact on the jazz standard All the Things You Are, recalls Konitz’s contrafact on that same tune, which he called Thingin’. Says Light, “That arrangement of mine has been kicking around for years, and I’ve played it so many times with friends that it seemed like a natural thing to do on this record, because it was something we could blow over without talking too much.

“It’s derived from a Ben Monder arrangement of All the Things You Are, where he takes the last bar off of every section. I learned this arrangement through Noah Preminger, who used to play with Monder a lot. But my idea was, ‘Why not do the same thing but then eliminate any bar with a repeated bass note or repeated melody note?’ So it turns into this cyclical-sounding piece that’s still recognizable as All the Things You Are.

It’s a one-page chart that just has the guitar part on it and no chord symbols or anything

“But then I did a Tristano-y approach to it, where I took these little melodic fragments and placed them around in a melodic, contrapuntal sort of way. My stuff will always be connected to him without meaning to, just because it was so influential to me when I found it.”

In any interview with Light – or if he’s just hanging with his colleagues, talking about music between Happy Hour sets at Bar Bayeux in Brooklyn – the name of Ben Monder is readily invoked. That Mondrian influence is apparent in the unusual chordal voicings, intervallic leaps and demanding string skipping heard throughout Chaotic Neutral, and particularly on his solo guitar introduction to the title track.

“I think that the band would agree that Chaotic Neutral is the most demanding composition on the record,” he says. “It has this odd-meter thing going that’s really messed up, but we played it so much at our regular Thursday gig at Bar Bayeux that, when it was time to do it, we just did it in one take.

“I had been working on intros for that tune because it’s such a nice harmonic situation to investigate in there. And I ended up taking this motif and improvising on it and slowly developing it into the material of Chaotic Neutral. So the intro is a semi-related motif to the composition, though I’m exploring it in a more abstract way.

“And Chaotic Neutral itself is definitely not atonal, but it’s almost adjacent to it in the way it explores extensions and stacks of chords. It’s my attempt at trying to make very dissonant tensions sound melodic – sort of an E flat minor over E minor over G major sharp-11th kind of thing.

“So there’s a ton of stuff going on in that tune, but it all derives from this sort of harmonic cloud that actually came from playing with Julian and having the ability to have a clear harmonic context to play around with, just to explore the limits of what I can hear on top of it.”

And while Brown Bear is another gnarly offering on Chaotic Neutral, tunes like the elegant Times Had and the delicate, Erik Satie–like Wash offer a calming breath after such intense playing.

“The harmony on Wash is definitely influenced by some French Impressionist stuff,” Light concurs. “And as soon as I had that particular chord – it’s an open-string G major, but also a minor chord – I was like, ‘Okay, I have the whole composition now,’ because it’s just going to be this thing that revolves around these very cloudy in-between major-minor chords.

“It’s a one-page chart that just has the guitar part on it and no chord symbols or anything, and I immediately could hear the way that these guys would be able to move and shape the thing.”

Although he admits holding such grips on the guitar for the song’s duration is “incredibly exhausting,” Light says, “I felt that sustaining each note of the chord was the most important thing about capturing the character of this thing.”

Still, it was too much for him to perform the song more than once during the album’s making. The two takes of Wash on Chaotic Neutral both feature his one performance. “We recorded Wash in one take, and I was like, ‘I can’t do it again,’” he says. “So that second take is actually them playing with my guitar part from the first take. It ended up being this very swirly, intricate thing. But my guess is Wash is probably not going to make too many appearances on the bandstand, just because it’s too much work for me. I mean, Ben Monder can do that shit. He can have it.”

There’s that name again.

“I don’t know if there’s anyone more influential to my compositional process than Ben Monder,” Light says. “I come from a relatively straight-ahead jazz background, coming up just outside Washington, D.C., so I always loved the great improvisers of Black American music in the 20th century, like John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Bud Powell, Bird, Miles Davis... But I’ve always loved playing metal guitar.

“I was into heavy metal, death metal and progressive metal long before I got into jazz and improvising. So when I found players like Kurt and Mike Moreno, Lage Lund, and Gilad Hekselman, there was something that was incredibly seductive about the way they were able to swing but still play modern, technology-based electric guitar. They play semi-hollow instruments, but they also use a lot of effects.

“Monder was huge for me as far as that goes. There’s stuff that Ben can do that is physically impossible for people. I took a lesson with him when I first moved to town, and he was playing diagonal bar chords – just a bunch of mini bars with the first joint of his fingers. It’s unfathomable!

“And I truly think that Monder’s music is going to be regarded in the future as classical guitar repertoire. He had a piece called Window Pane on his album Excavation that I think is one of the greatest works for solo guitar ever composed. It’s so beautiful and subtle, and the way the harmony shifts and returns and the way he develops that stuff is just amazing. My own tune Dennisport, from Herplusme, is 100 percent derivative of Monder. You can’t escape the influence of Monder.”

The POG2 has this compressive quality that allows me to cut through or blend with horn players or into an ensemble

Light has similarly high praise for guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel. “His compositions, his improvising, his sound, his way of articulating and the way he uses his right hand – it’s all hugely influential for me,” the guitarist says. “He deeply affected me and deeply influenced the way I think about music and the way I physically think about the instrument I play. I think Kurt is easily one of the most important guitar players in the history of the instrument.”

Discovering the POG2, the pedal that allows Rosenwinkel to eliminate the sound of his picking attack, was a huge breakthrough for Light. “I couldn’t fathom how light he was playing with his right hand,” he explains. “It was just so delicate and nuanced, and he was able to pull so much sound out of the guitar that it sounded like he was bowing the strings.

“So I started cranking my amp and trying to play as quietly on the instrument as possible, simultaneously, to get that sort of light-touch articulation thing going on. And that was years before I found the POG2. It has this compressive quality that allows me to cut through or blend with horn players or into an ensemble. It’s almost like I developed in the direction of using this thing, and that totally unlocked my way of playing.”

Another primary influence for him was the late, great Allan Holdsworth.

“He’s like ’Trane,” Light exclaims. “The amount of information he was searching for and playing, and the sophistication of his harmonic concept that he was channeling through his completely profound technique is just unbelievable.

Allan Holdsworth is untouchable, unimpeachable... I would build a shrine to him

“I was drawn to it because of all of the metal guitar players that I grew up listening to – like the lead guitar player of Meshuggah [Fredrik Thordendal]: When you listen to the way he improvises, it’s immediately obvious that this guy is into Holdsworth.

“Holdsworth is, like, untouchable, unimpeachable. His total pursuit of understanding music and speaking the language as fluently as possible is astounding. He is just the total king. I would build a shrine to him.”

A self-described “serial monogamist” when it comes to guitar, Light played his Collings I-30 semihollow exclusively (through a Harry Colby–modified Deluxe Reverb amp) on Chaotic Neutral.

“Prior to that, I had been playing a D’Angelico DC Premier, which was my pandemic guitar,” he explains. “I just played it to death, basically. That’s the guitar I played on Henceforth, and it was starting to fall apart. So a couple of months later, for my 30th birthday, I got this Collings guitar that I had my eye on forever.”

Light found his Collings at TR Crandall, a vintage guitar shop on Ludlow Street on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

“I was like, ‘Oh, man, it’s over for me – this is it!’ And as soon as I got it, man, I was like, ‘Okay, now I’m a professional musician – this is a real instrument.’ I mean, it was on such a higher level than anything I had ever played before.

“So this is my guitar now. It’s a semi-hollow with Loller humbuckers in it. The thing sounds amazing and it only weighs, like, five pounds, which was the icing on the cake. Being a professional guitar player in New York and having to take the trains all the time, having a light setup is essential.”

That portable rig will come in handy in the coming months, as it has in the past. When he’s not touring Europe in pianist Christian Sands’ quartet or with Kaisa’s Machine, led by the Finnish-born, New York City–based bassist Kaisa Mäensivu, or gigging locally in saxophonist Kevin Sun’s quartet, Light, and a rotating cast of his Brooklyn colleagues, can always be found at their regular Thursday hang from 5:30 to 7:30 at the 700-square-foot Bar Bayeux in Prospect Lefferts Gardens.

And if he’s not there, he’s probably woodshedding. “I’m a great believer in the virtues of noodling on guitar,” Light offers. “I think if you talked to any one of my teachers, they would basically say of my entire life, ‘He never shut up. He just never stopped playing while we were talking.’ And I’m still like that to this day.”

- Max Light's new album, Chaotic Neutral, can be purchased or streamed now.

Bill Milkowski's first piece for Guitar Player was a profile on fellow Milwaukee native Daryl Stuermer, which appeared in the September 1976 issue. Over the decades he contributed numerous pieces to GP while also freelancing for various other music magazines. Bill is the author of biographies on Jaco Pastorius, Pat Martino, Keith Richards and Michael Brecker. He received the Jazz Journalist Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 and was a 2015 recipient of the Montreal Jazz Festival's Bruce Lundvall Award presented to a non-musician who has made an impact on the world of jazz or contributed to its development through their work in the performing arts, the recording industry or the media.