“There’s a riff that represents my twisted idea of how Aerosmith might sound in 5/4”: How Guthrie Govan channeled his inner Steve Reich, and Steve Cropper, on the Aristocrats' humorous, musically dazzling new album, Duck

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

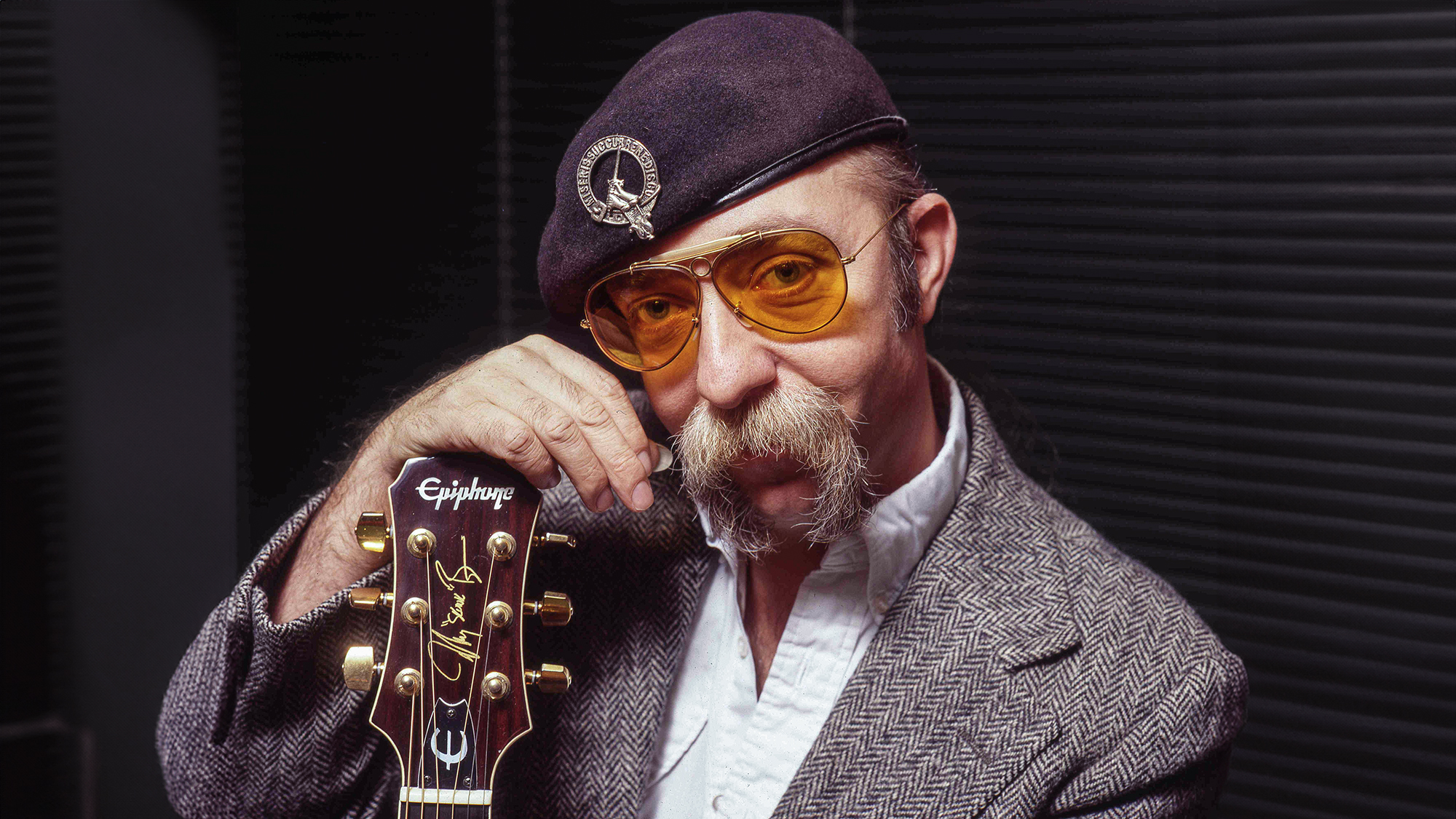

Fourteen years ago, a group of super-serious musicians – guitarist Guthrie Govan, bassist Bryan Beller, and drummer Marco Minnemann – formed a band after an impromptu NAMM show jam. Ever since then, they’ve been doing everything they can not to take themselves so seriously.

“Boring fusion is pretty much the antithesis of what we’re going for,” Govan attests. “We’ve always wanted to create something a little more fun and subversive. Our foremost priority was never to showcase ourselves doing things on our instruments that the audience might not be able to do on theirs. We feel like a genuine sense of joy emerges whenever we play together, so that’s really the foremost thing that we want to share with the listeners.”

Govan is right about one thing: The Aristocrats are a good time. They have released four albums of rowdy, wildly unpredictable and irreverent instrumentals – everything from crushing metal, psycho funk, spacey jazz, and mad dashes of swing – with song titles like Sweaty Knockers, Blues Fuckers, and The Kentucky Meat Shower. But the idea that mere mortals could replicate the dizzying chops of this highly pedigreed trio is somewhat fanciful.

After all, Beller has recorded and toured with Joe Satriani and Steve Vai, Minnemann’s résumé boasts names like Tony Levin and Steve Hackett, and Govan has worked with Hans Zimmer and Steven Wilson, among others.

“Of course, it would be disingenuous of me to play down the importance of us being able to operate our instruments at a relatively high level,” Govan admits. “That stuff is essentially the foundation for everything else.

“If we couldn’t play well enough to perform our music with the required degree of technical proficiency while maintaining enough headroom to accommodate our more chaotic and improvisational side, then the whole thing would fall apart. That’s why I said that showcasing the musicianship element was never our foremost priority.”

Following a five-year hiatus, the trio has reconvened for its latest album, Duck. From the ferocious metal-swing gem “Hey – Where’s MY Drink Package?” to the feisty riff-banger Sgt. Rockhopper and the grandiose musical theater conceit of This Is Not Scrotum (get past the title and you’ll be imagining Cabaret mixed with Fiddler on the Roof), it’s an orgy for fans of virtuosic rock, full of wicked grooves and bravura soloing.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

There’s even a loose narrative element to the whole thing, something about

a web-footed water bird fleeing a penguin cop in New York City. As Govan explains, “One of Marco’s song submissions was called Sittin’ With a Duck on the Bay, and that somehow led to us to make an entire concept album in which the central protagonist is a duck. It’s funny how these things can happen.”

All of your albums, including this one, have nine songs each. Looks like you still adhere to that “three songs per guy” rule.

“We still adhere to that principle. It’s served us well over the years, so why change it? When we’re working on a new album, all three of us make a real effort to write material that we think would complement the band’s component musical personalities. Hopefully, that leads to stronger and more suitable material overall.”

A few years ago, you told me that you write with two aspects in mind: a tight focus on composed sections, and an eye toward open sections that leave room for jamming. Has that changed?

“Not at all. That’s been the most flexible aspect of every demo I’ve ever sent to Marco and Bryan. Amid the detail in the more heavily composed sections, there will typically be a solo section or fade-out jam accompanied by the note: ‘This section could be stretched much further if we’re feeling it.’

“I like the idea of having live material that offers the scope for playing the songs differently every night. A typical album touring cycle for us will last 100 shows, so having some extra flexibility baked into the arrangements can really help to preserve everyone’s enthusiasm and sanity.”

Can you point to any songs or passages on which any new guitar influences were in your head?

“There were certainly some moments where I channeled influences in a way that people might not have heard from me before. Subconsciously, for instance, I was almost certainly thinking of Steve Reich when I came up with the tapping loop that runs throughout much of Slideshow. And there’s a riff in Here Come the Builders that represents my twisted idea of how Aerosmith might sound in 5/4.

“I guess the main guitar character in Sittin’ With a Duck on the Bay was me trying to adopt a kind of ’60s–’70s mindset, in my own weird way.”

You do seem to emulate Steve Cropper in places on that one.

“I think Marco’s intention was to pay tribute to a whole genre or period of music rather than that Otis song in particular. But I suppose being aware of the song title may have steered me slightly closer to Cropper territory.

“I wasn’t actively trying to sound like anyone in particular, but I did make a conscious decision to use an ES-335 straight into an old Fender Deluxe for the main guitar voice on that track. Somehow, the 335–Fender combination just looked the way I thought the guitar should sound on that track.”

Overall, was your main guitar your signature Charvel model?

“For the most part, yes. The studio in Ojai, where we did most of the tracking, is full of vintage guitars, and I can never resist the temptation to try out unusual alternative instruments. However, my main takeaway, almost every time, was a renewed appreciation for just how stable and reliable those Charvels are.

“Having said that, you’ll hear plenty of 335 on Sitting With a Duck. In the middle of Muddle Through I used my Nik Huber Orca ’59.

“After realizing that the studio’s Danelectro 12-string was a bit too jangly to work convincingly as a lead instrument, I used a Reverend Airwave 12 on This Is Not Scrotum. I ordered it online, something I’ve never done before. Oh, and the clean solo interlude in And Then There Were Just Us was done on a Gretsch G100CE – not the fanciest of jazz archtops, but that particular model has no center block in the body, and that allows the top to vibrate more freely.”

When you’re not playing with the Aristocrats, you regularly perform with Hans Zimmer. Do you need time to decompress from such a radically different gig before playing with this band?

“In an ideal world there would always be time to decompress when switching musical gears, but in the real world, needless to say, this luxury isn’t always available. Earlier this year, I encountered a particularly messy calendar clash where my Aristocrats and Hans Zimmer duties actually overlapped.

“At any rate, I’ve discovered that I can indeed switch from one mode to the other pretty quickly when I need to. I think the simple act of moving into the surroundings of a known touring environment will instantly activate certain mental triggers, so everything tends to come flooding back pretty quickly. On the other hand, if I’m trying to record something remotely for one band while I‘m on tour with the other, that’s a different story. My brain definitely struggles with that.”

- The Aristocrats' Duck is available now.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.