Black Francis and Joey Santiago Discuss the Past, Present, and Future of Pixies

The alt-rock legends talk writing and recording their latest album, 'Beneath the Eyrie', and the band’s increasingly mythologized past.

“We like things that sound a little 'off' or unsettling," Pixies singer, rhythm guitarist, and primary songwriter Black Francis explains. "We don’t want it to sound wrong with a capital W, but if you can get away with having one little thing that just kind of makes it a little bit weird, like, ‘What’s going on here?,’ that’s a good thing.”

At this point, the Pixies have made a career – make that two careers – out of doing things that are a little bit weird. The Massachusetts-based band’s first run, highlighted by classic late-’80s albums like Surfer Rosa and Doolittle, established them as something of an indie-rock Velvet Underground – not especially successful in the mainstream, but massively influential to the generation or two of rock acts that followed in their wake. (Once, when describing the quiet-verse/loud-chorus format of Nirvana’s hit “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” Kurt Cobain famously said he was “basically trying to rip off the Pixies.”)

That influence only grew after the Pixies broke up in 1993, to the point that, upon reuniting a decade later, they received a hero’s welcome, playing to crowds that were arguably larger (at least in the U.S.) than any they’d experienced in their heyday.

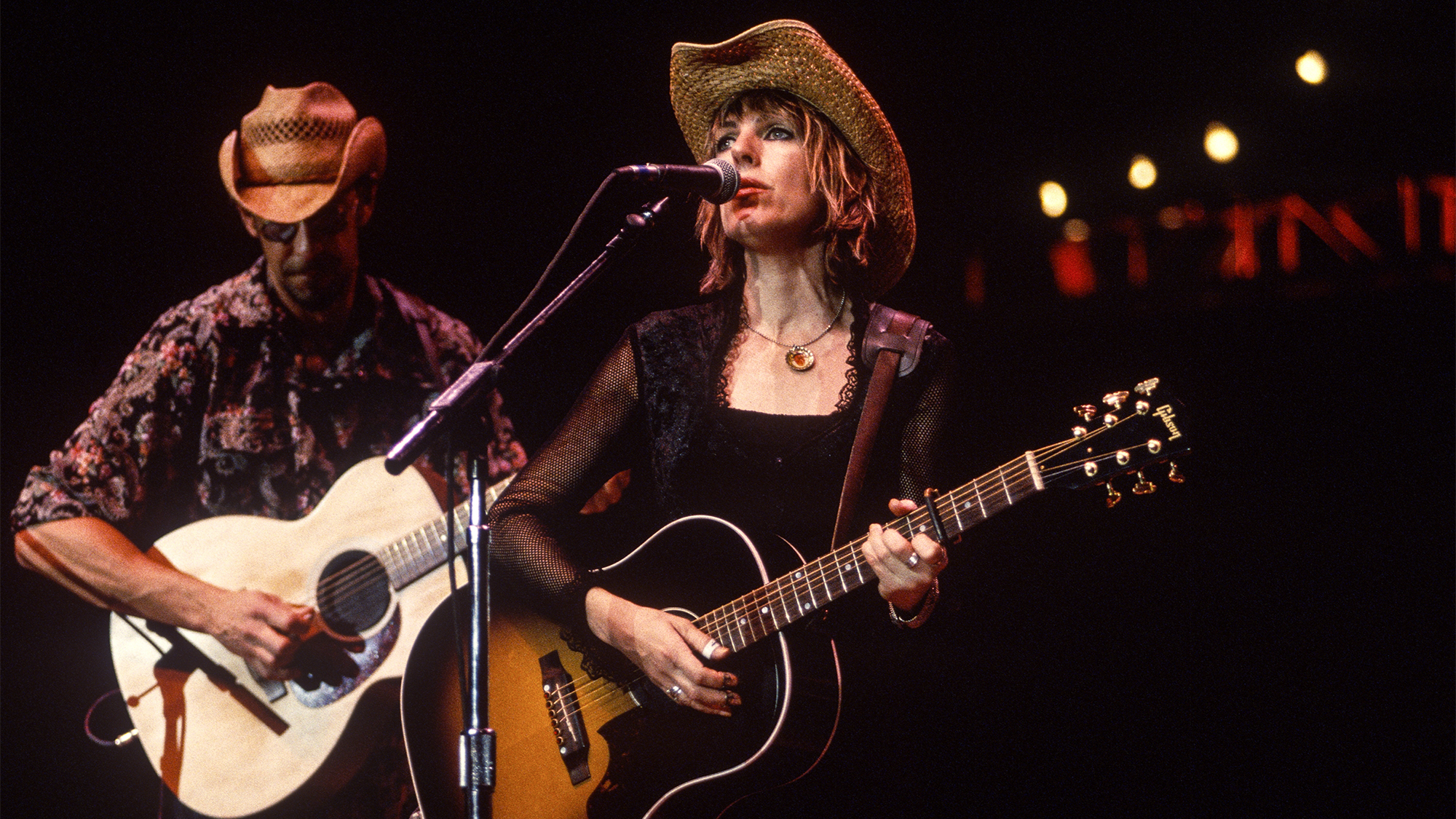

Since then, the Pixies – Black Francis (born Charles Thompson), original lead guitarist Joey Santiago, original drummer David Lovering and more recent addition bassist Paz Lenchantin, who fills the spot vacated by original member Kim Deal – have released a trio of studio albums, starting with 2014’s Indie Cindy and continuing with 2016’s Head Carrier.

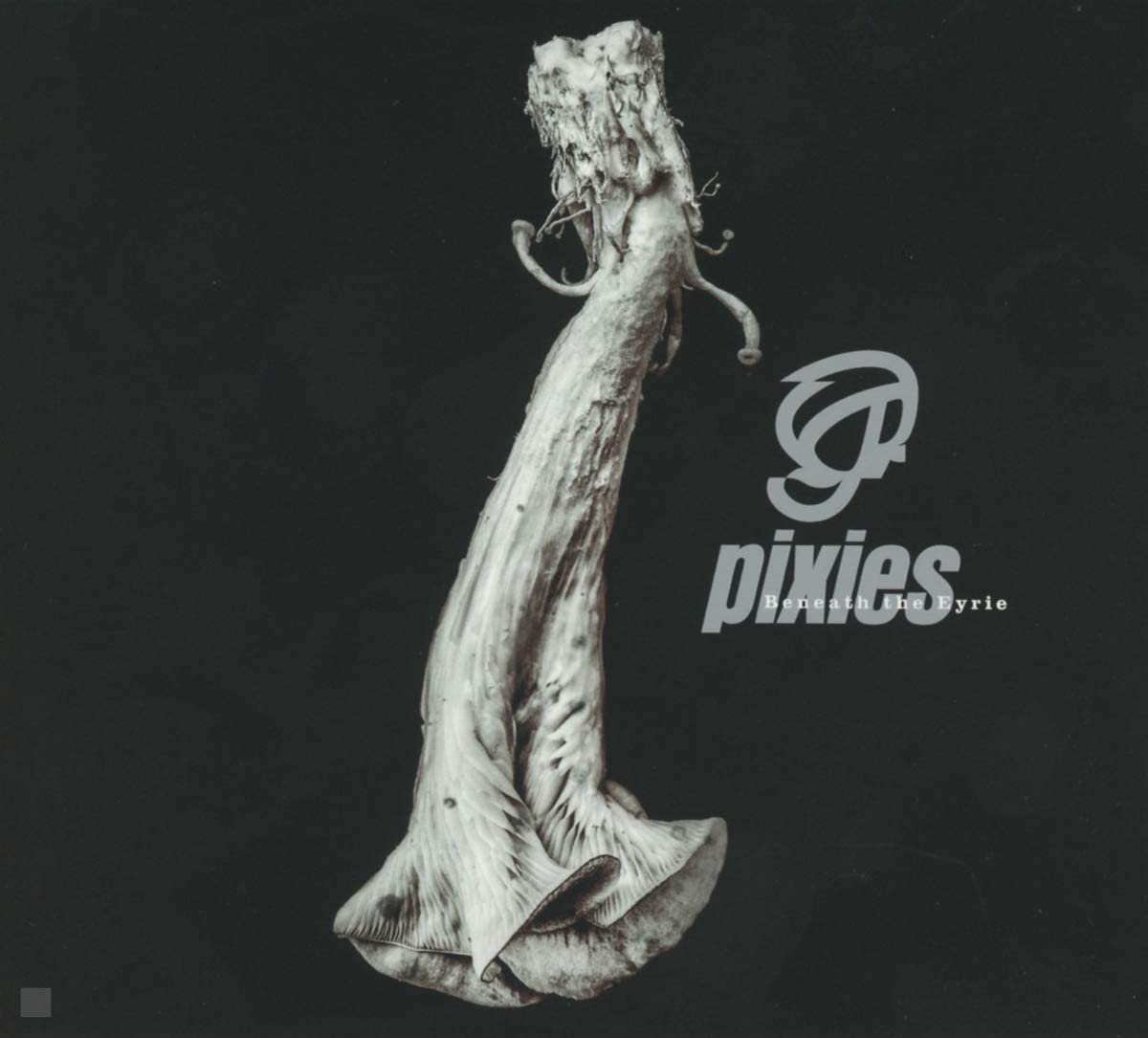

Their latest studio album – 2019’s Beneath the Eyrie (BMG/Infectious) – hearkens back to the sound of their late-’80s efforts. Its tracks include the ominous, droning opener titled “In the Arms of Mrs. Mark of Cain,” the demented surf rock tune “St. Nazaire,” and the throttling first single, “On Graveyard Hill,” characterized by Santiago’s buzzing electric guitar melodies and Thompson’s ever-more agitated vocal.

The band even gets downright anthemic – but still, of course, a little bit weird – on “Long Rider.” The record reminds listeners what made the band so legendary to begin with, while it demonstrates that the Pixies are far from a nostalgia act.

Beneath the Eyrie is arguably the strongest of the three studio efforts you’ve put out since reuniting. Did you go into this record with any particular intentions?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joey Santiago: Not really. We were just coming in with a collection of songs. We demoed it, we weeded out the ones that were the weakest – or what Tom [Dalgety, producer] thought were the weakest ones – and we made the record we were comfortable making. But we didn’t really have any intentions of what it should sound like.

Black Francis: We usually try not to get too boxed in by any preconceived attitudes. We mostly just want it to be interesting and not boring. But if there was one suggestion that was on the table, I suppose it was the very loose idea of “the gothic,” whatever that means.

Whether it was literary or in a cliché way, or even in a way that sounded musically like so-called goth music, there was this idea that if the gothic showed up, and if it revealed itself, we wouldn’t fight it.

At the very least, there seems to have been an element of the gothic present in your choice of studio environment. You worked at Dreamland Recordings in upstate New York, which was once a 19th-century church.

Santiago: Oh, yeah. We were in an old church, it was the wintertime. Things were dead. If we made this record at the Grand Canyon, I would say it probably would have had a different vibe.

Francis: But we would never pick a studio based on, you know, “Is the ambience going to work for the theatrical affectations that we’re sort of sporting?” It’s much more that we showed up and it was, like, me and [Tom Dalgety] going – wink-wink – “Looks pretty gothic out there, eh?”

But the environment was very headless horseman, the swamp, the ghost in the attic. It had all of that kind of stuff going on. So that was nice.

Charles, in a recent podcast chronicling the recording sessions for the album, you mentioned that on the first day of tracking you almost hit a herd of deer on the way to the studio.

Francis: Yeah. I was in a big cargo van with a bunch of gear in it, and I was thinking about this new chord shape I was working on two days before that I liked. I needed a lyric for it. I’m really glad I didn’t have an accident. But I just looked at it like a Buddhist death philosophy kind of thing, where you try to appreciate your life by imagining you’re about to die.

So I was able to take that little moment from before the session and be like, “What if I had hit the deer? Let’s tell the story of that guy.” And it’s a song on the record called “Daniel Boone.”

Speaking of chord shapes, how do the two of you work together as guitarists?

Santiago: Charles will bring in an idea or a lyric or maybe a melody. And then, for the most part, I’m always just concentrating on little chunks of the song. I treat every part – verse, chorus, bridge – as its own entity, its own little song. And the overall goal is to try to have some kind of string around an idea within the verse, chorus, bridge – all the parts – and have that dictate the feel.

But I’m basically at the service of the song. I’m either the shadow in it or a little light in it. It depends on what the song is.

Charles, what do you see as Joey’s role?

Francis: The biggest role Joey has is that he makes it sound like the band. Because when I’m writing a song, it doesn’t always sound like a quote-unquote Pixies song.

Sometimes I’ll make a demo, and it will have the bass and the drums and some rhythm guitar and even my voice, and it still doesn’t necessarily sound like a Pixies song. But when Joey turns on his guitar amplifier and starts to play something, even if it’s a bunch of mistakes because he’s still learning the song or whatever, it’s like, “Oh, now it sounds like the Pixies!” There’s this big shift in terms of the sound of the band.

Joey, your style is so distinct, but it’s also hard to define. It isn’t easy to pick out, say, blues or country or classic rock influences in your playing. Who are some of the artists you’re inspired by?

Santiago: Well, Ennio Morricone would be one. And another would be Steve Reich. He doesn’t use guitars, but he gets a lot of good, cool tones with xylophones, violins – things like that. And I read somewhere that Jimi Hendrix was inspired in his guitar playing by sax players. That had a lot of influence on me, the idea of making a guitar sound not like a guitar. It’s just a different way of thinking.

You’ve said that when you were younger, you wanted your guitar to sound like a drill.

Santiago: That just happened to be because of the gear I had at the time. My first amp was a Peavey, and it had this control called saturation, which is a great fuzz knob. And when you turned it up, it made the guitar sound like a power drill! [laughs]

Francis: If you know Joey, when you hear his guitar playing, it’s like, “Oh, yeah, of course that’s what he sounds like.” I can honestly say that his personality is very much represented in his style. I say this because, in all of the musical analysis that goes on in writing about our records, he probably doesn’t get enough credit for how much his playing makes the music sound like the Pixies.

It’s often said that a lot of alternative- and indie-rock bands over the years have copped your style. Do you ever hear it?

Santiago: I didn’t until someone pointed it out. We were at a festival, and the band playing was Cage the Elephant. I forget the name of the song – it may be “Trouble” [from 2015’s Tell Me I’m Pretty] – but it does sound a lot like [the Surfer Rosa track] “Where Is My Mind?”

Francis: Every once in a while I hear some band where I think, Oh, yeah, they’ve definitely heard a couple of our records. But it probably happens a lot less than people think. We get asked about it a lot, as if it’s this common thing: “Oh, there it goes again, that old Pixies thievery!” And I don’t know how I feel about it, because that reduces what we do.

“That other band sounds just like you guys.” It’s like, “Really? We sound like that? I hope not, ’cause this isn’t very good!”

Do you feel like the Pixies sound does get reduced too easily to just a few sonic elements? The quiet-verse/loud-chorus dynamic shifts, for instance, or the whisper-to-a-scream vocals?

Francis: Well, yeah, sure. But what are you going to do? If we get reduced to, “Oh yeah, they’re doing that loud-quiet-loud thing,” or, “They’re doing that screaming thing that they do,” I mean, sometimes it feels a little simplistic. But I’m old enough now where I’m not really offended. It’s just like, “Wow, welcome to showbiz!”

When you go onstage these days, what does a Pixies crowd look like?

Francis: I can’t really get too sociological on you. But when you get a little older, and you get audience members that have heard about you by reputation and maybe weren’t even born when you made the records that they’ve come to hear, there’s a little bit of reverence going on.

They’re like, “Okay, I finally get to go see this band I’ve heard about my whole life.” They’re not necessarily whooping it up. We get confused sometimes, because we think, ‘Oh wow, we’re not going down too well, are we?’ And then we realize everyone’s just trying to be respectful and not act like a bunch of yahoos.

Has anything about the band’s second run been particularly surprising to you?

Santiago: The only surprise I had was when we reached the seven-year mark, which was longer than we were together the first time.

Francis: To be honest, I just accept it, because I didn’t really imagine anything. Whatever I use my imagination for, it’s usually much more escapist in nature. It’s not like [adopting snooty accent], “What’s it going to be like in 20 years? What will my audience be like then?” I don’t really care about that. I’m imagining other things that are a lot more abstract or personal or whatever.

Do you imagine the Pixies can continue indefinitely?

Santiago: It’s up to us and the fans still having passion for it. And that could be fleeting. But so far it’s a good relationship between the Pixies and the people out there.

Francis: The way I see it, everyone seems to be liking what we do, so we probably shouldn’t mess with it too much. And anyway, it’s not like we had that much of a blueprint in the first place, you know what I mean?

Buy Beneath the Eyrie by Pixies here.

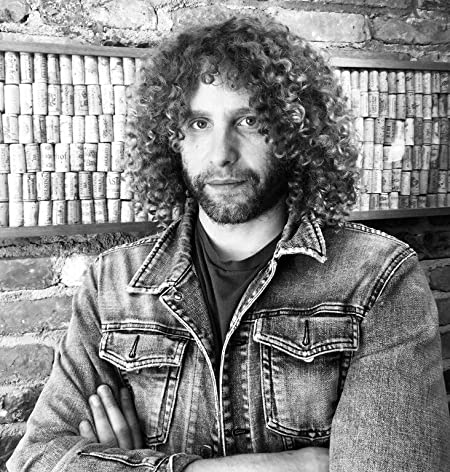

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.