Prepare to Have Your Learning Reality Altered With This Enigmatic Scale

A fresh approach for mastering the altered scale, the elusive 7th mode of melodic minor.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I’ve been playing the guitar and studying music for over three decades. Throughout my time spent woodshedding in the name of mastering various scales and all their various modes, one scale in particular traditionally vexed me. After years of trying to harness the potential of this Voldemort-like “scale that must not be named” (not yet) with otherwise successful methods, I realized I had to change my approach. I needed a new reality, one that entailed re-examining the importance of naming conventions, embracing enharmonic equivalents (different names for the same pitch) and, perhaps the most jarring, using chords to inform my learning of a scale.

I speak of the altered scale, which is the seventh mode of the melodic minor scale. Now, it’s our standard practice to spell out a scale’s intervallic formula in parentheses when it’s first mentioned. This temporary omission is fallout from the theoretical rebellion the altered scale wages, which I will attempt to quell in this lesson.

To the uninitiated, the altered scale presents itself as a formidable foe, with its enharmonic tendencies and formulaic duality, as well as its multiple names. Regarding the latter, in your own quest to learn about the altered scale you may have already discovered the relatable names super-Locrian or Locrian b4, or maybe more descriptive names like altered-dominant (my favorite) or diminished whole-tone (my second favorite).

If you’re looking for more commemorative or exotic names, then consider dubbing this organized order of elements the “Pomeroy,” “Ravel” or “Palamidian” scale.

Whatever name suits your fancy, the fact remains the altered scale is a challenging proposition to wrap your head around. All that said, to get the most from this campaign, prepare to have your own scale learning reality, well, altered.

As I mentioned, the altered scale is the seventh mode of melodic minor (1, 2, b3, 4, 5, 6, 7), which ironically has its own naming saga. The historical use of melodic minor, in classical music, calls for the scale to follow the formula you see here as it ascends; when it descends, however, it shifts to the parallel natural minor scale, or Aeolian mode, formula (1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, b7), where the 6th and 7th degrees are lowered a half step.

“Jazz minor” is an alternative name that helps differentiate the manner in which melodic minor is played by modern improvisers, where the scale retains its makeup regardless of the direction it’s played.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

At face value, the altered scale is intervallically spelled 1, b2, b3, b4, b5, b6, b7. From a C root, the notes are C, Db, Eb, Fb, Gb, Ab, Bb.

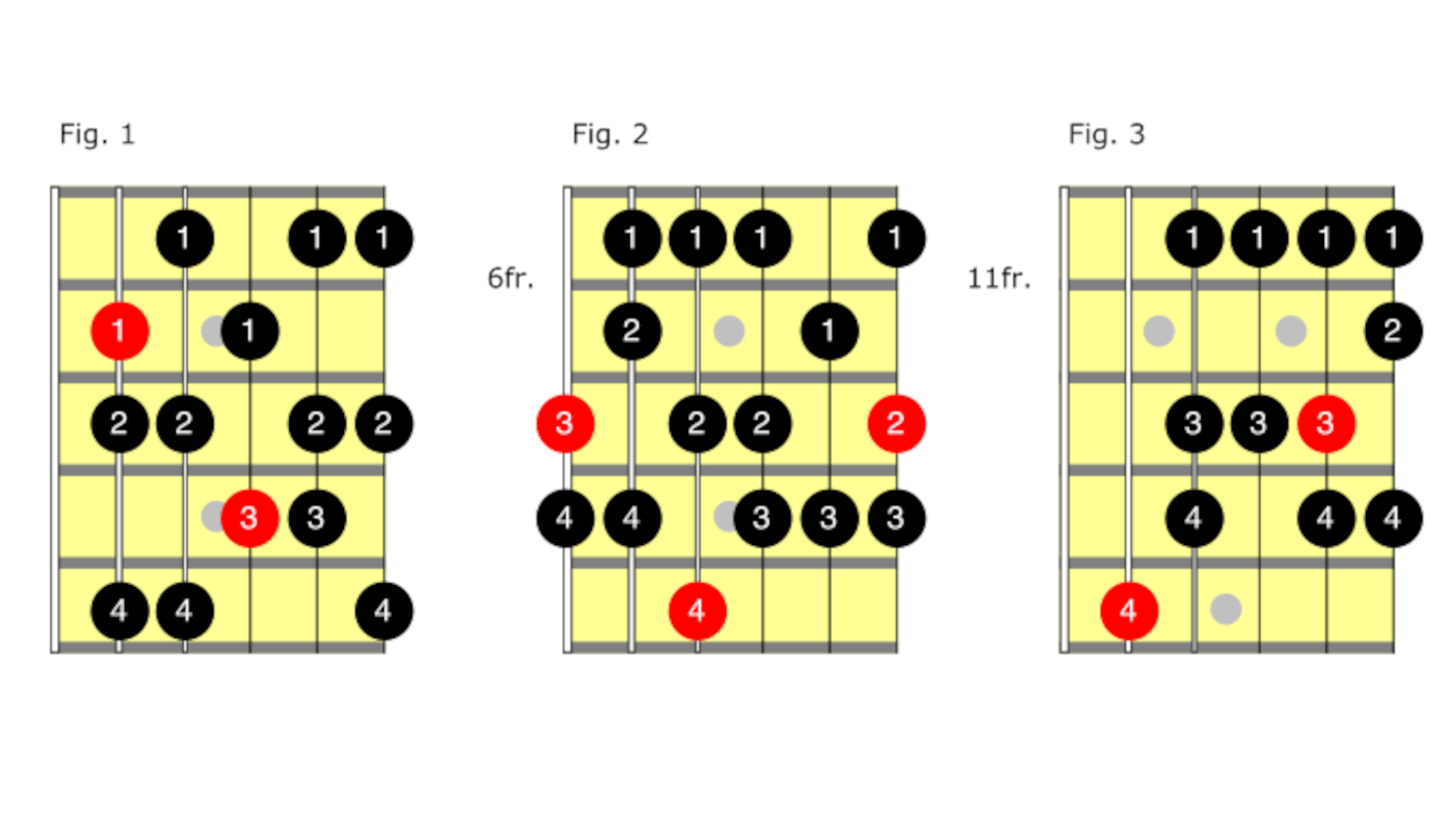

As you ponder the who, what and why of that diminished 4th (Fb), play through the patterns illustrated in Figures 1–3, ascending and descending, to get a feel for the sound as well as the somewhat archaic fingering possibilities of this enigmatic device.

About that b4th degree: this is where names like super-Locrian and Locrian-b4 originate, since the rest of the scale spells out a Locrian formula (1, b2, b3, 4, b5, b6, b7). However, looking at the scale from this perspective robs you of the treasure that awaits.

Setting aside the honorary naming conventions, the gold within the altered scale is revealed when you consider the more descriptive names such as altered-dominant and diminished whole-tone. The former hints towards the scale’s flavor and function while the latter spells about valuable insight into the idea of formulaic duality.

With a shift in perception, let’s spell the altered scale as C, Db, Eb, E, Gb, Ab, Bb. Notice the enharmonic shift from Fb to E. Although they are indeed the same pitch, reckoning the 4th degree of the scale as E reveals its true value as a major 3rd of C.

In conjunction with the b7th degree (Bb) you can fully appreciate the nod to a dominant 7 chord (1, 3, 5, b7) that the altered scale offers and thus the notion of perhaps calling this scale altered-dominant.

Regarding the “altered” nomenclature, this describes the function of the remaining scale tones – Db (b2), Eb (b3), Gb (b5), Ab (b6). These “outside”-sounding notes provide tension over the first half of a V7 - Imaj7 cadence, for example, thus creating a more intense sounding resolution that’s attractive to jazz guitar, fusion and modern blues guitar players.

Examples 1-3 show a trio of V - I lines in the key of F – C7 to Fmaj7 – where the C altered scale could apply. The licks will feature each of the three scale fingerings in Figures 1-3, respectively, to begin to give you a taste of what this approach has to offer.

Respelling the scale one more time, as well as shifting a few choice scale degree assignments, chew on this iteration: C (1), Db (b2), Eb (b3), E (3), F# (#4), G# (#5), Bb (b7). From this perspective, you can start to wrap your head around the idea of calling the altered scale the diminished whole-tone scale (1, b2, b3, 3, #4, #5, b7).

With the major 3rd (E) serving as a shared axis point, we can split this scale down the middle, with the initial four notes resembling the first half of a symmetrical diminished scale formula (1, b2, b3, 3, #4, 5, 6, b7) – also known as the half-whole scale, due to the repeating step pattern – and everything north of the major 3rd mirroring the last four notes of a whole-tone scale formula (1, 2, 3, #4, #5, b7), which, as its name implies, is made up of successive whole tones, or steps.

Both the symmetrical diminished and whole-tone scales in their totality are viable options for supplying lines with tension over dominant 7 chords, as well.

With the altered scale name game addressed and some, albeit not all, of the talk about enharmonics fleshed out, the attention shifts to establishing a neck vision through chords. You might still be thinking, “Chords? I thought this was a lesson about getting better control over a scale.”

The approach centers on this thought: Scales are melodic devices meant to be in constant motion while chords are fixed, stationary harmonic devices.

With regards to the latter, chords are easier to picture and thus visualize on the neck. In conjunction with that notion, think of chord tones as markers on a trail with myriad pathways.

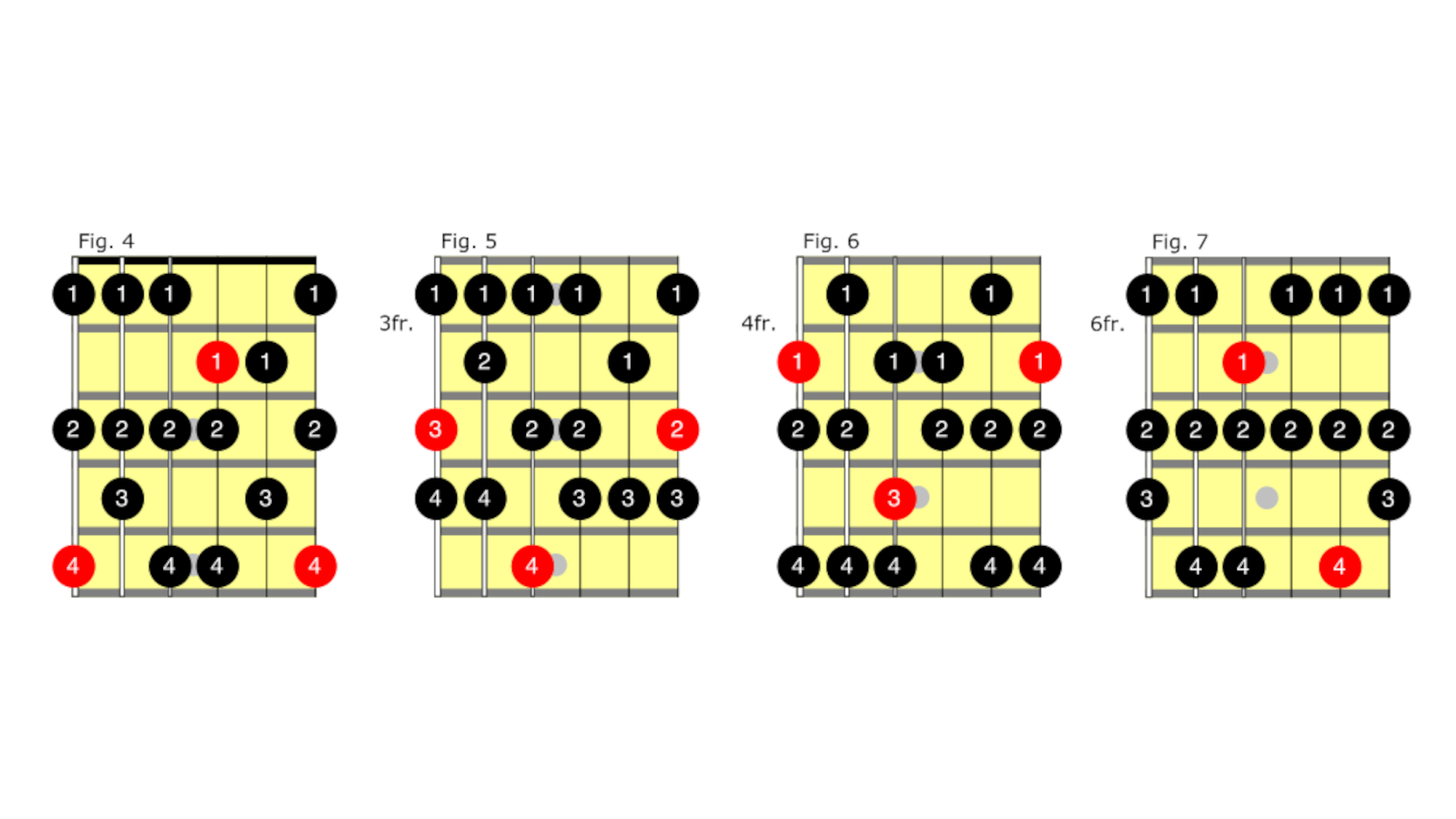

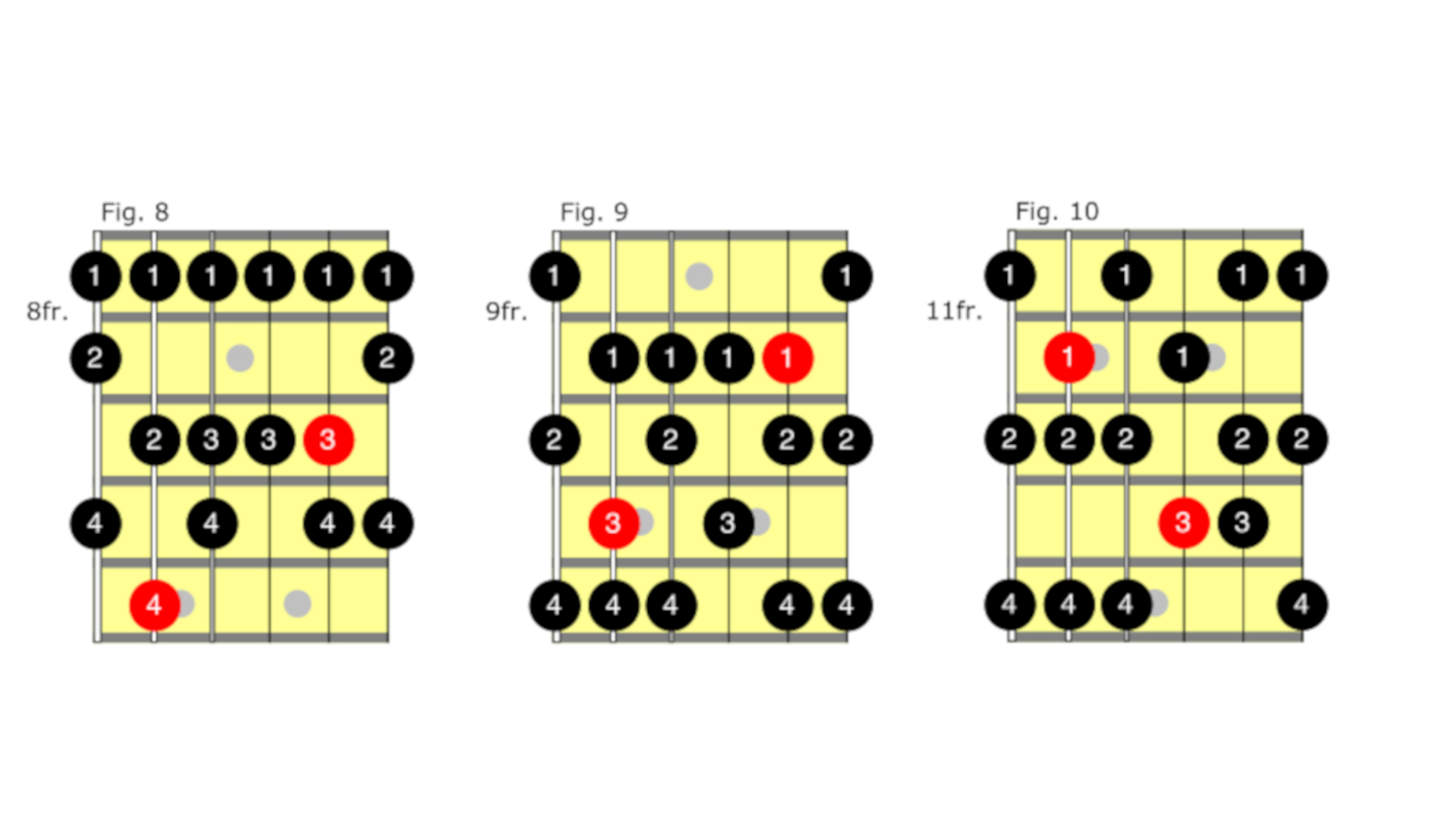

To get started, you need a complete series of altered scale fingerings that end on successive scale tones. These will serve as your pathway. Figures 4-10 provide just that, with a collection of fingering patterns for the A altered scale (A, Bb, C, C#, Eb, F, G) that make their way up the neck, starting with a pattern that climbs up to a 5th-fret A root on the high E string. (The A root notes are circled in red in all of these diagrams, in every octave where they occur.) It should be noted that the lowest note in each of these seven patterns (i.e., the note you start on, on the low E string, fretted with the 1st finger, is a successive scale degree, with the first and lowest pattern beginning on the #5 (F).

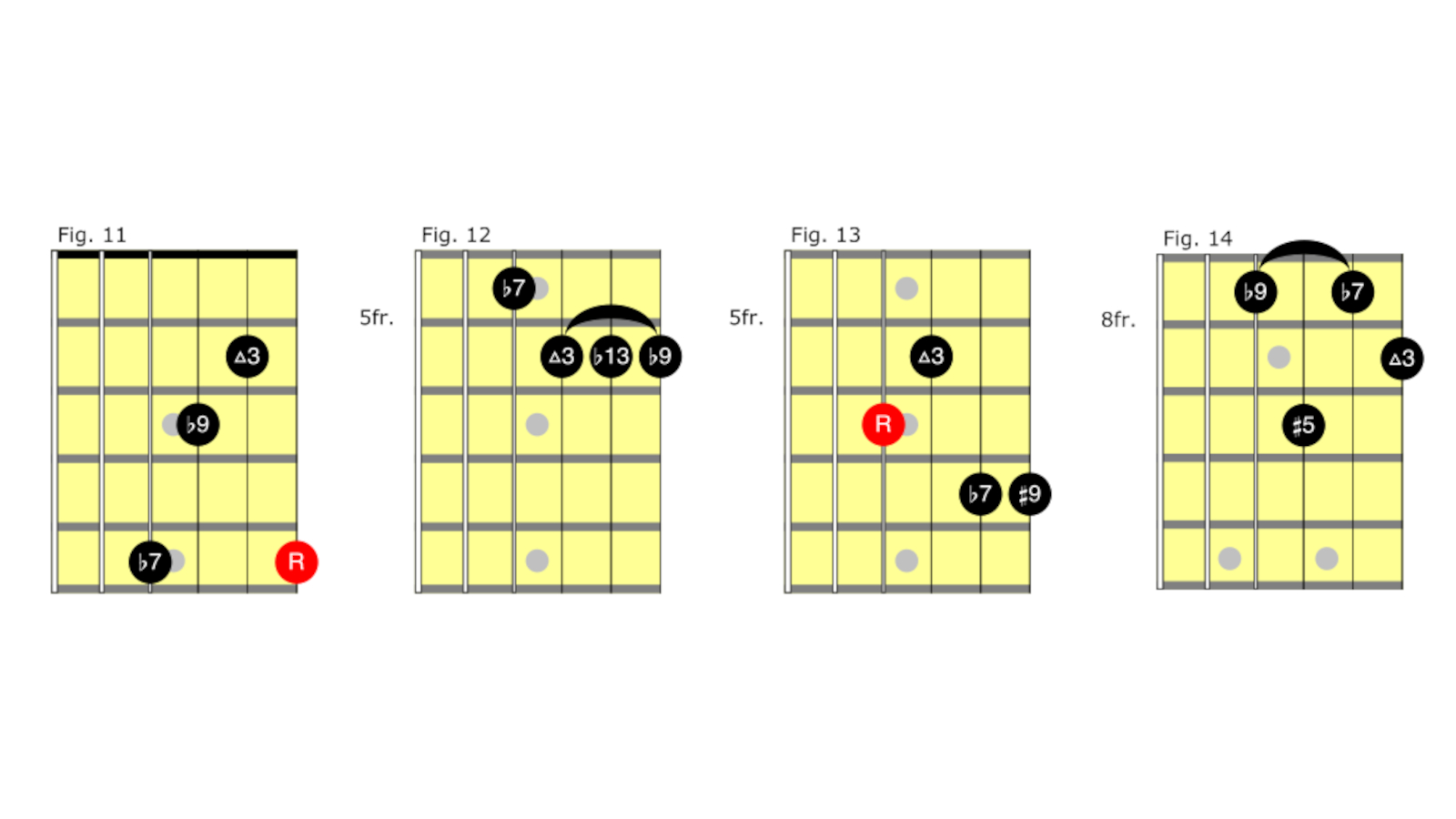

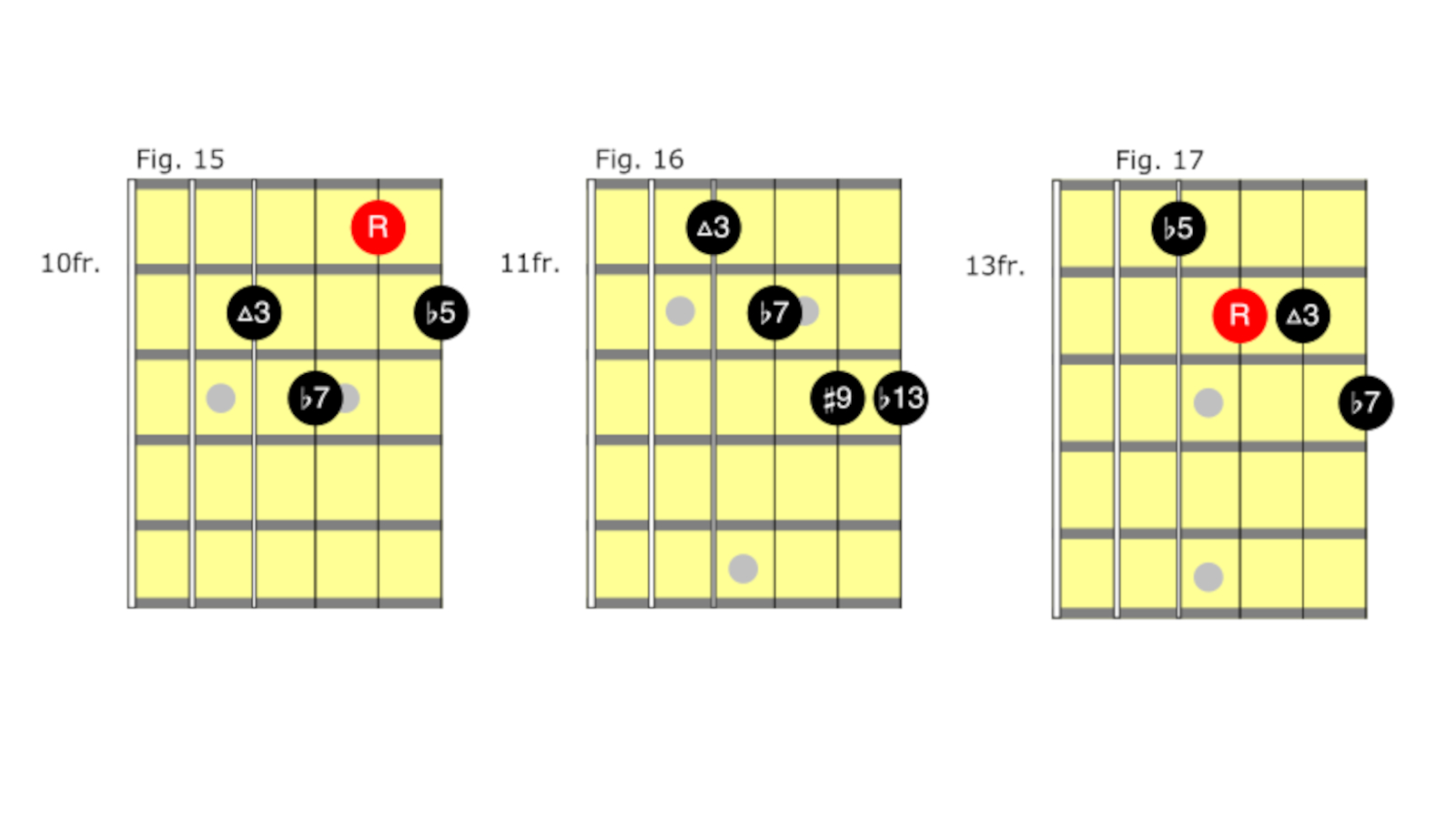

For each of these patterns, I assign a corresponding altered-dominant-7 chord shape, illustrated in Figures 11-17, respectively, which similarly contain root-note markers, highlighted in red circles. The connection between the scales and chords rests on the highest note of each chord purposefully matching the highest note of the scale pattern it’s mated with.

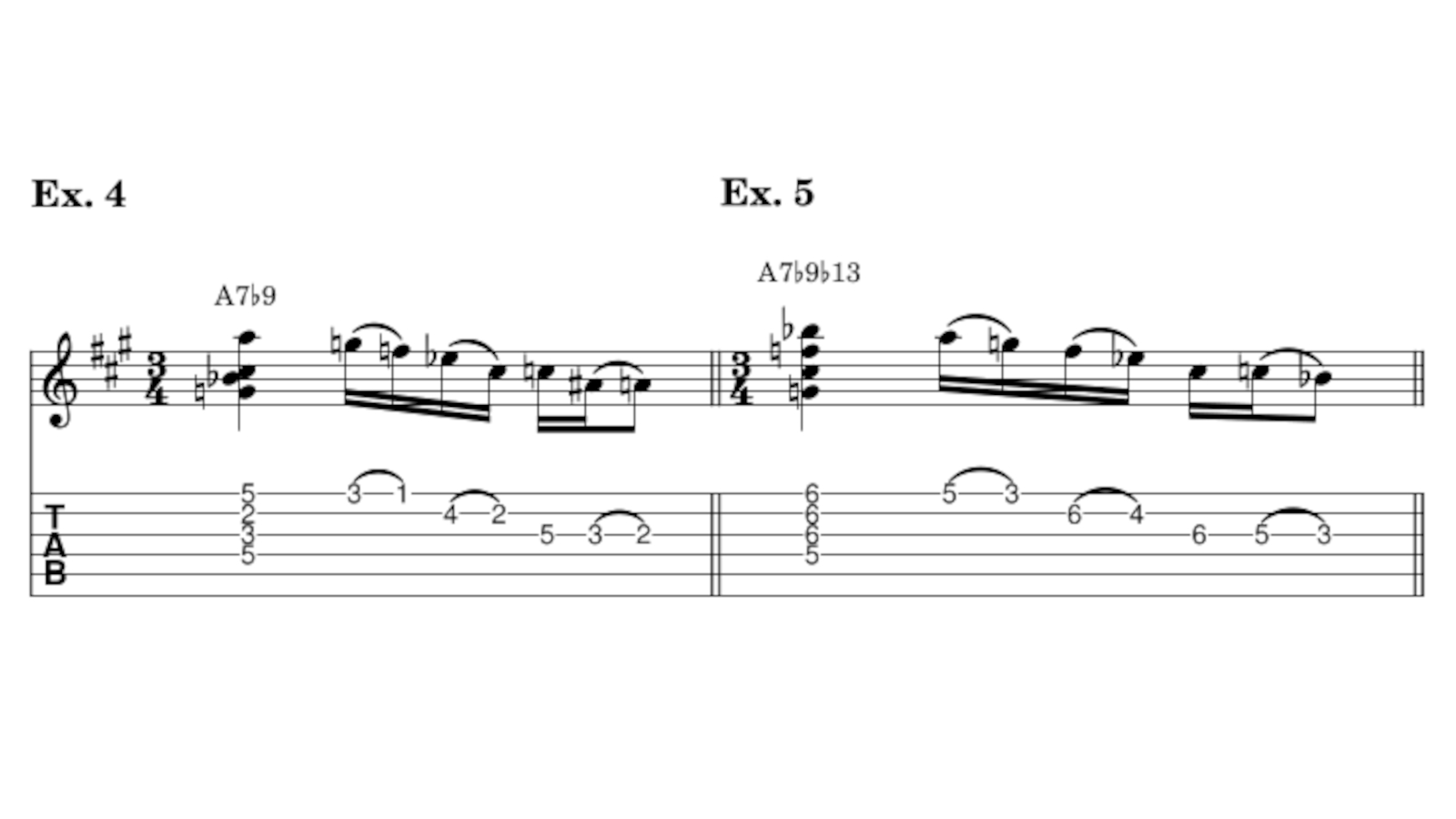

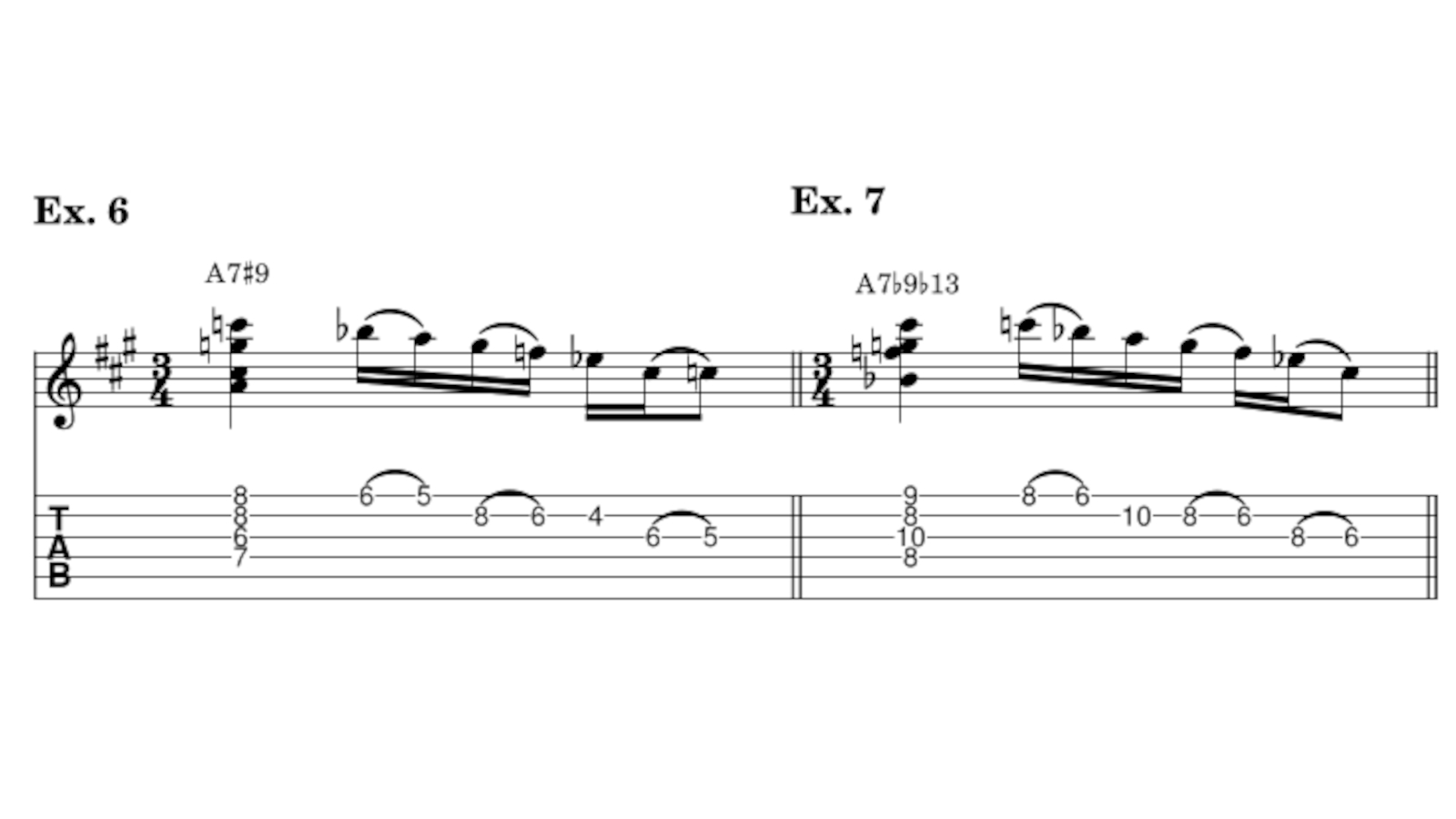

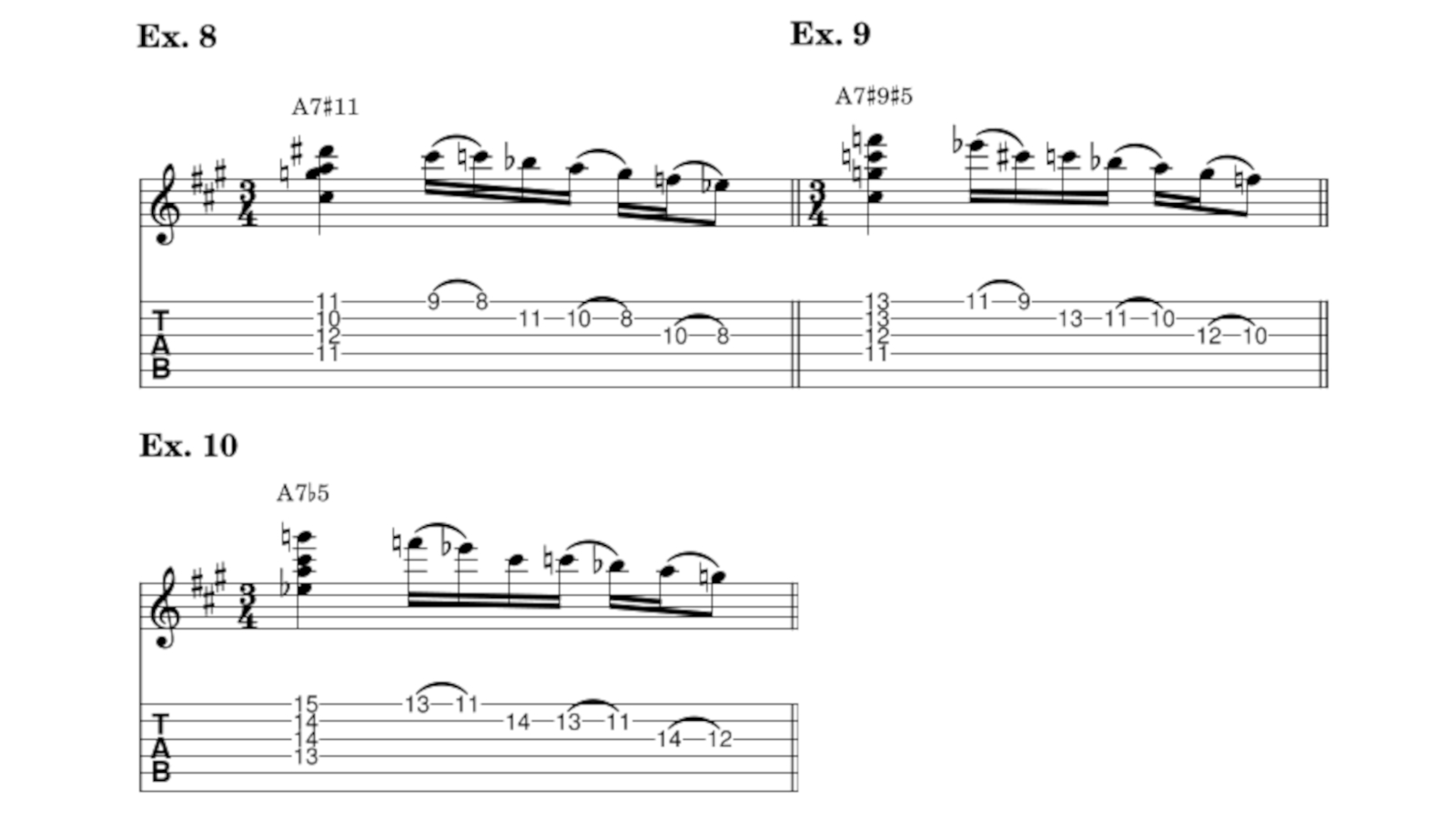

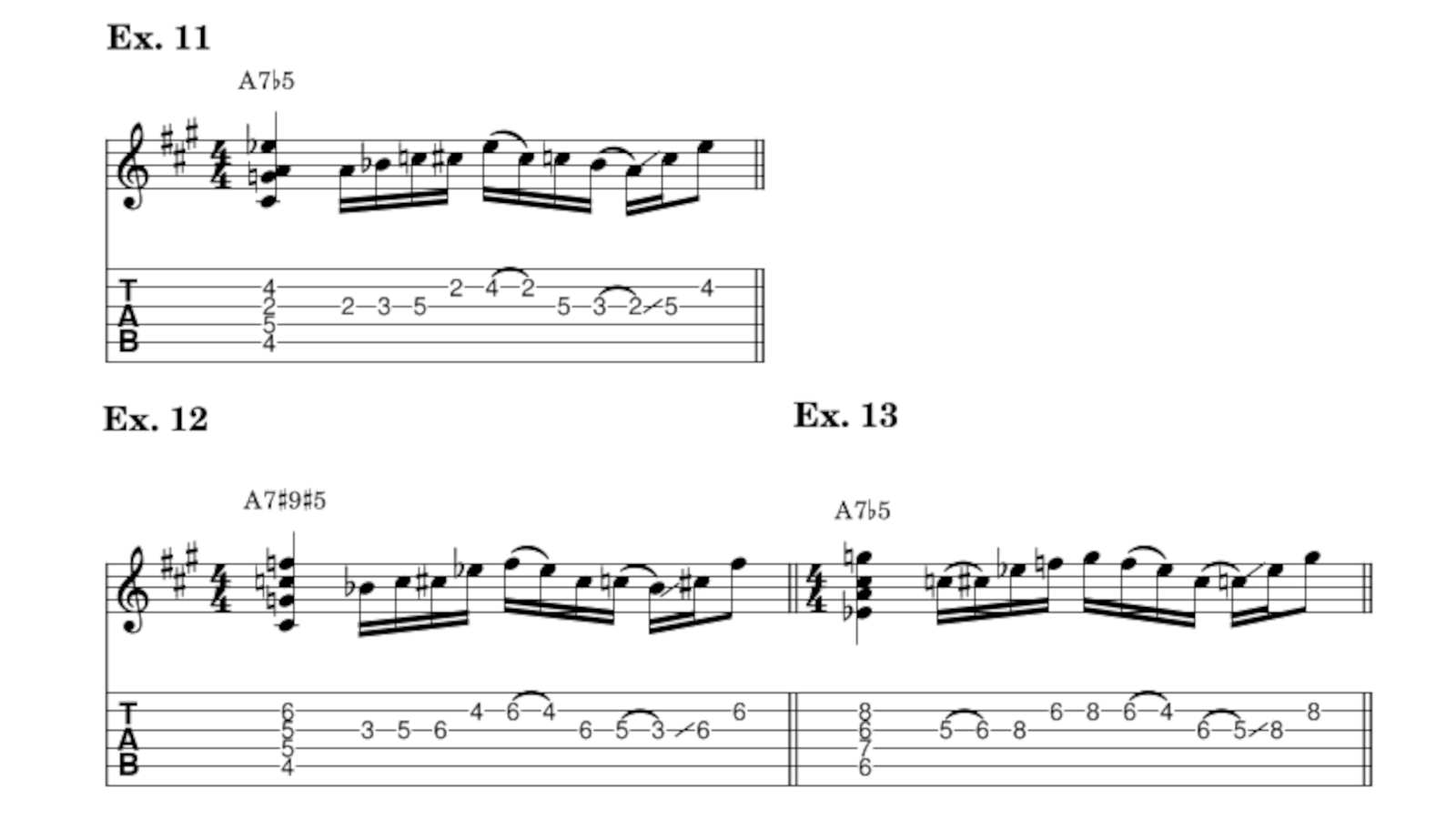

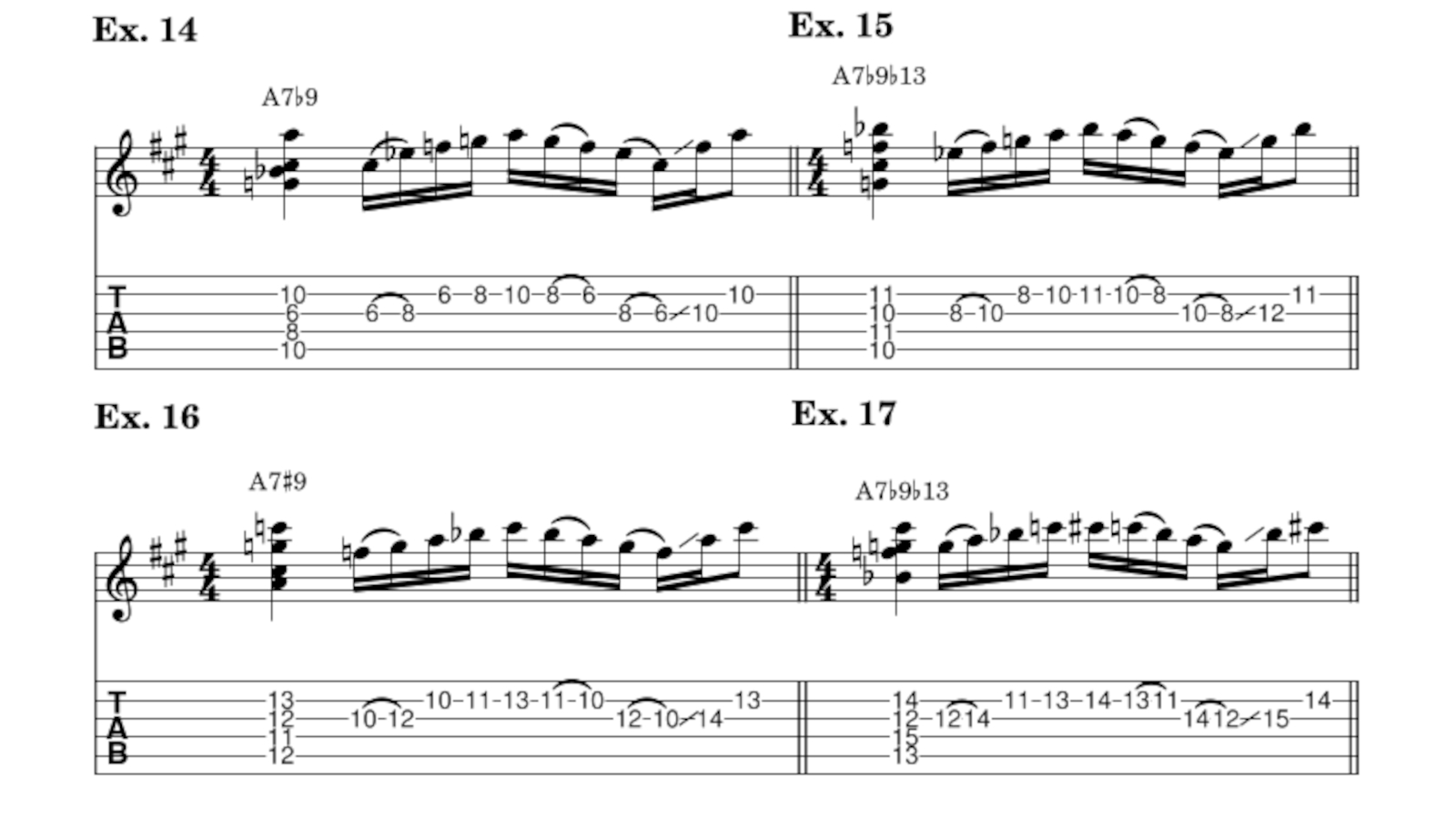

To begin to illustrate and cultivate this system, the phrases in Examples 4-10 have you playing the associated chord that goes with each scale pattern before playing a descending line on the top three strings. With the exception of Ex. 5, each chord’s highest note fingering is common with the scale it’s connected to. This makes for a smooth legato-like transition from the fixed harmonic altered entity to its ever-flowing melodic counterpart.

Even better, within those short descending bursts you’ll pass by more markers in the forms of chord tones, as you walk your fingers down that particular pathway.

As you review Examples 3–9, you may notice altered extensions, such as b9, #9, #11 and b13 in the chord names. Another challenging facet of the altered scale and the harmony it breeds is the liberal use of what are called upper extensions when naming scale and chord tones.

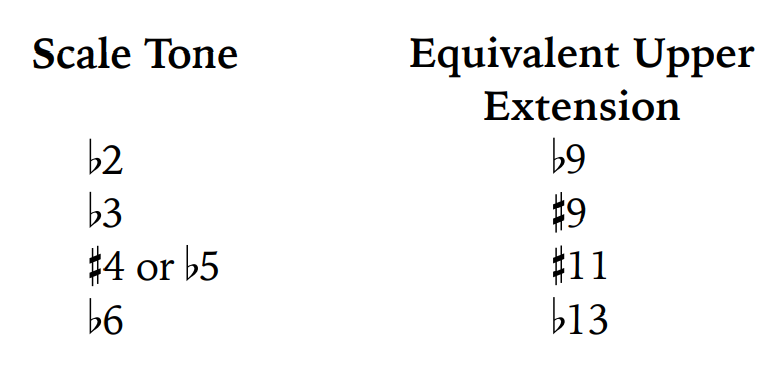

More often than not, players experienced in extended harmony of all types will freely label scale degrees within the simple range (first octave) as extensions found in the compound range (second octave). Below is a table that addresses all of the possibilities:

You may also have picked up on the use of #5, despite not having an E# in the spelling provided for the A altered scale. The liberal approach to designations also includes enharmonics – one player’s #4 is another player’s b5. Be patient with this; it will come. In the end, with time, you will not only start to be versed in the possibilities, but you’ll also develop your own naming conventions.

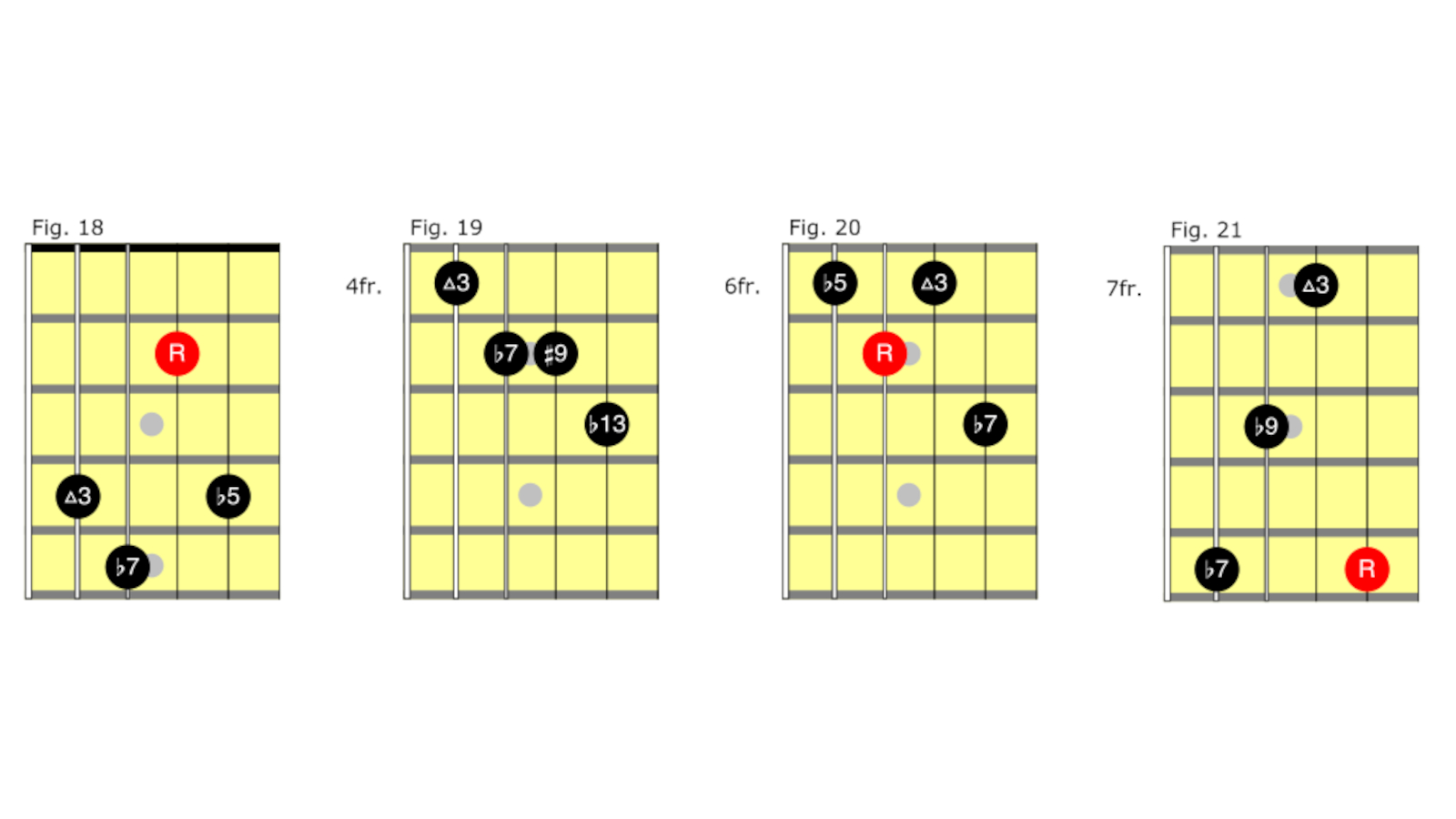

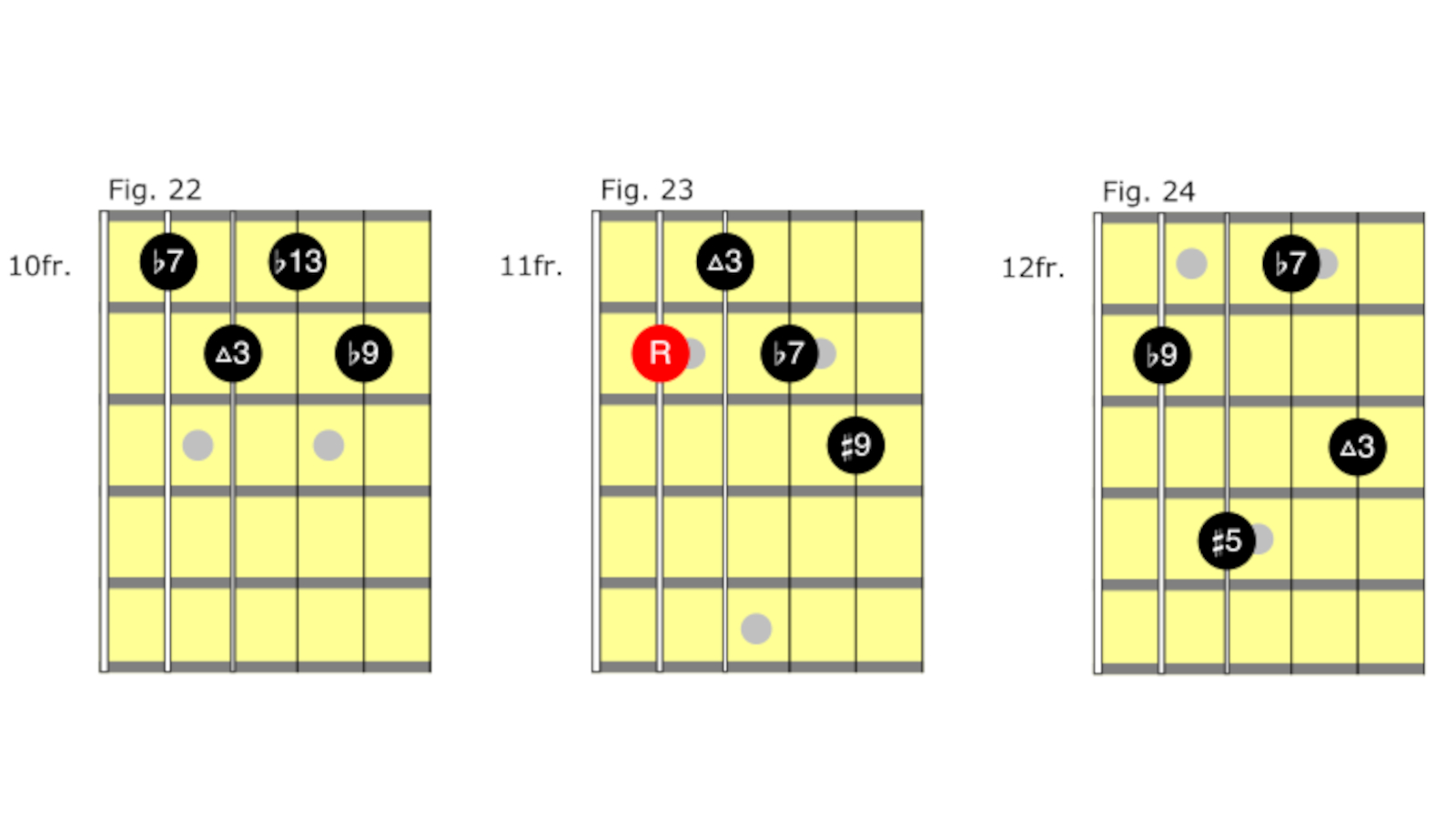

Let’s have another go at aligning those same A altered-scale patterns in Figures 4-10 with same altered-dominant chords, this time with grips on the middle four strings, as illustrated in Figures 18-24.

This time, the match is on the B string, where both the highest note of each chord voicing is common with the highest note of the associated scale pattern. You’ll find another approach to the idea of pathways in Examples 11-17. The fingerings for the chords are slightly different, despite the voicings remaining the same, due to the major-3rd tuning relationship between the G and B strings.

Embrace this concept and invest time into transferring your entire chord vocabulary to neighboring string sets.

It’s a powerful skill to have and will bolster your neck vision tenfold!

I hope this method helps you develop your own reality with the altered scale, one where you harness its full potential and take it even further. I encourage you to compose your own pathways and systems of markers to help drive home this concept.

As you woodshed these examples, along with your own ideas, be sure to regularly apply slight changes along with modulating through all 12 keys. These practices will not only solidify this new reality, but all the ones to follow.

Chris Buono is a top-selling TrueFire Artist with nearly 50 instructional videos, and a featured instructor on guitarinstructor.com. Bookending his years as a Berklee professor, he authored eight books, including the popular Guitarist’s Guide to Music Reading and his most recent publication, How to Play Outside Guitar Licks.