“I Was Instantly Humbled”: First Call Session Guitarist Carl Verheyen Shares Rare Insights Into Allan Holdsworth’s Unorthodox Chord Voicings – as Revealed by the Man Himself

“This concept of spreading out the notes of a chord into wide-interval voicings like this resonated with me years later,” says the Supertramp alumnus and seasoned solo artist

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This is a classic GP lesson column from session guitar veteran Carl Verheyen.

When I first met Allan Holdsworth in the ’70s, he invited me over to his house to jam. All I knew about him was what I’d heard on Bill Bruford’s One of a Kind album.

With one listen, it was instantly apparent that this was a very different guitar player. Sitting across from the innovative genius and playing with him was already intimidating enough, but one day, we decided to play his new song, “Three Sheets to the Wind.”

To my ears, his concept for chord melody seemed to be aligned with Ted Green’s famous book, Chord Chemistry, in that the three notes in a major triad may be voiced on any trio of strings, using any combination of intervals.

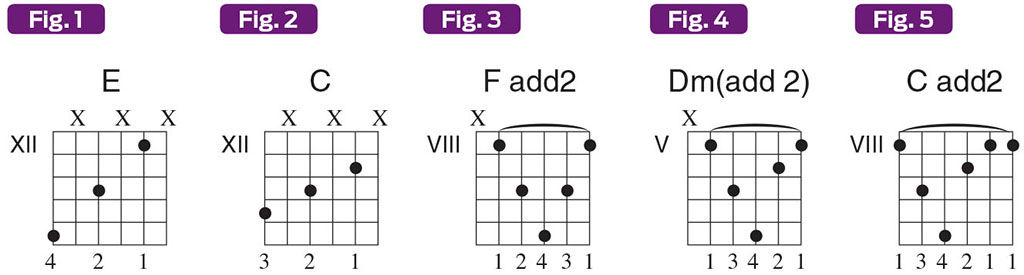

Notice the E chord in Fig. 1. The third, G#, is on the bottom string with the root in the center of the chord and the fifth on top. (Use either hybrid picking or straight fingerpicking to sound the notes together.)

The C triad in Fig. 2 compresses the outer notes, as they contract in contrary motion from the previous chord, while the E note on the fourth string stays common to both voicings.

This concept of spreading out the notes of a chord into wide-interval voicings like this resonated with me years later, when my own chord vocabulary began to develop. I find it interesting that sometimes we learn something we’re not yet ready to absorb and apply, but, years later, the light bulb goes on and we get it.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But on that first day, I was instantly humbled when Allan showed me the chord voicings he used for the soloing changes in “Three Sheets to the Wind,” because my left hand couldn’t form the shapes quickly and cleanly enough.

I limped home with my tail between my legs, and the next morning I locked myself in a room with a guitar. I refused to come out until I could go from a first position C chord to each of the wide-grip, pinky-stretch voicings illustrated in Figures 3-5 – each of which includes a note cluster of a minor-or major-second interval.

From a first-position “cowboy” C chord, keep your second finger on the fourth string and slide it up to the C note at the 10th fret. Now, try to lay your fingers down simultaneously on the rest of the notes in Fig. 3, thrusting your pinky out there to grab the third string’s G note at the 12th fret.

Practice this C-Fadd2 change over and over again, until the first-finger barre and other three fingers learn to come down all at once. Then, practice switching back and forth from Dm(add2) to Cadd2.

It took a little while until I could get these kinds of unorthodox chord voicings under my hands and incorporate them into my playing. But that was Step One.

Step Two – actually blowing over those changes – was a much harder challenge.