Faux Nashville Tuning is Just a Few Computer Clicks Away

Like Nashville tuning but can't abide those string changes? Here's our guide to a smart computer-based workaround.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Nashville tuning delivers a bright, chimey guitar sound typically heard on country sessions but also on rock recordings.

The alternative method described in this column takes a computer-based approach. It isn’t exactly the same as Nashville tuning, but it has a similar musical function in a mix.

Traditional Nashville tuning retains a guitar’s 1st and 2nd strings, but uses the 3rd through 6th octave-higher strings from a 12-string set (or a Nashville tuning-specific string set, such as those from D’Addario and GHS). It sounds like this should be a simple conversion, but conventional Nashville tuning takes commitment: You either dedicate a guitar to it or change strings a lot!

Conventional Nashville tuning takes commitment: You either dedicate a guitar to it or change strings a lot!

In addition, changing string tension this much affects the guitar. You’ll likely need to adjust the intonation and possibly the truss rod. Some who dedicate a guitar to Nashville tuning use a 12-string guitar, because the nut is cut appropriately for the octave-higher strings.

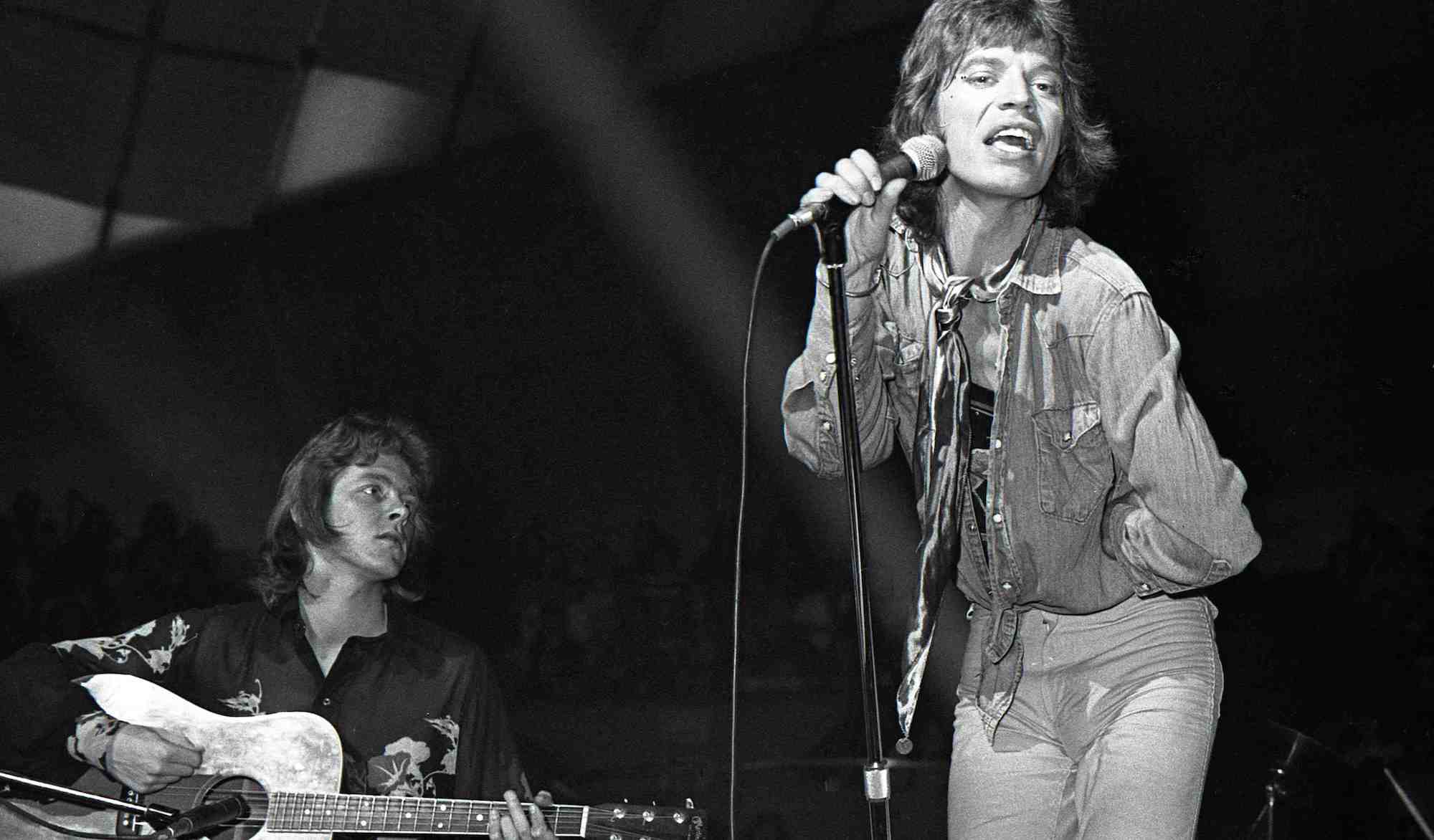

"Hey You" from Pink Floyd's cinematic masterpiece, The Wall, is a great example of Nashville tuning. But also check out the Rolling Stones' "Wild Horses," on which Mick Taylor plays an acoustic in Nashville tuning, complementing Keith Richards' 12-string acoustic and electric.

How To Do It

This method doesn’t involve changing strings, but you’ll need to transpose your guitar track an octave higher using digital signal processing (DSP).

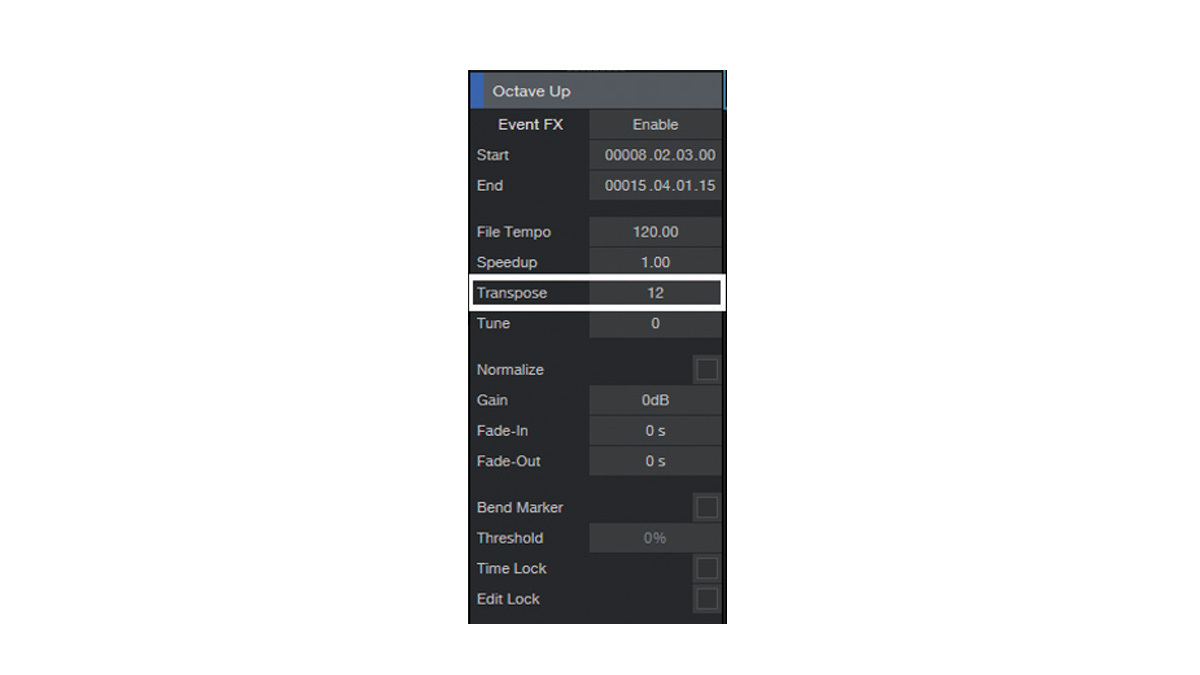

Pitch-transposition algorithms have improved greatly, and the one in your DAW may be all you need (Fig. 1). Celemony Melodyne can also do pitch transposing, and even some harmonizing pedals or multi-effects will work.

But note that the effect generally sounds better when rendered - that is, when the effect is applied as a final recorded treatment - than it does when applied real time; so does playing cleanly. With electric guitar, I prefer using the neck pickup, with its tone control rolled back.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Adding EQ

Unlike a Nashville-strung guitar, DSP transposes the 1st and 2nd strings up an octave, along with the others. You may like the results, but for a more traditional sound, use EQ to dial back the high frequencies and add warmth (Fig. 2).

You can use a low-pass (high-cut) filter or a couple of parametric stages, but I prefer to use shelving EQ if it has a Q (resonance) parameter. Turning up the Q somewhat adds a peak that boosts the upper mids, and also cuts the highs more substantially above the corner frequency.

The drastic cut below 200 Hz enhances the bright, jangly sound. Many players layer Nashville-tuned guitars with a conventionally tuned guitar playing the same part, and cutting the lows keeps the Nashville-tuned part from “stepping on” the other guitar.

Going Further

Transposing up two octaves can also be interesting. If you reduce the high-frequency response (e.g., a 36 dB/octave high-cut filter starting around 6 kHz), and lower the level to help mask the artifacts that occur with extreme transpositions, the sound acquires an almost organ-like quality.

As with some previous columns, I’ve created an audio file that illustrates the results of this technique, which you can hear below. The first third is acoustic guitar, and the second third is the transposed sound by itself, while the final third combines the two.

- Visit craiganderton.org for more articles, videos and free downloads.