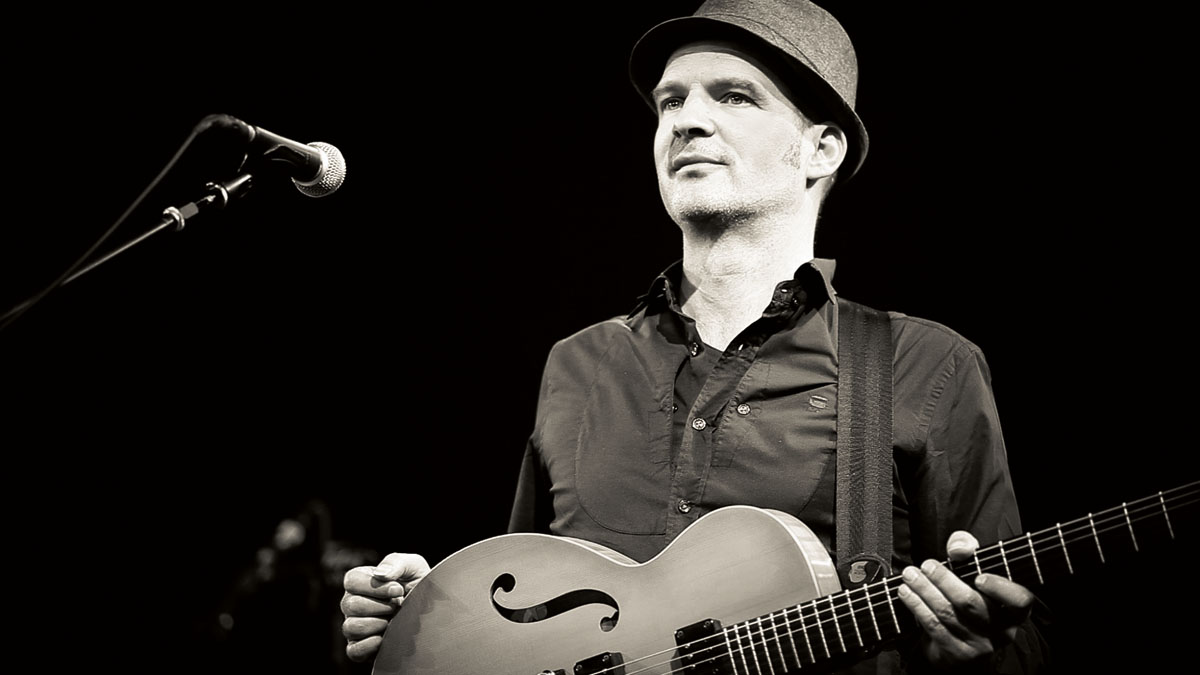

Wolfgang Muthspiel on Technique, Composition and Why Three is the Magic Number for Making the Guitar Talk

On 'Angular Blues,' master improvisor Wolfgang Muthspiel brings his conversational approach to a trio setting.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

American guitar aficionados have known about Austrian guitarist Wolfgang Muthspiel for nearly 30 years, going back to his two-year tenure in Gary Burton’s band during the early ’90s and his own acclaimed 1991 debut on Antilles Records, the Burton-produced The Promise.

That record featured the potent lineup of tenor saxophonist Bob Berg, pianist Richie Beirach, bassist John Patitucci and drummer Peter Erskine.

Muthspiel followed in 1992 with the more biting Black and Blue on Polygram before he joined drummer Paul Motian’s Electric Bebop Band in 1994 and bassist Marc Johnson’s Right Brain Patrol in 1996. He returned back home to Vienna in 2002 and started up his own Material Records label.

Muthspiel’s reputation as a master improviser with an uncanny ability to cast a six-string spell was enhanced by a number of superb recordings. They included 2003’s Real Book Stories, his exploration of jazz standards in a trio setting with bassist Johnson and Wayne Shorter drummer Brian Blade, and 2007’s Friendly Travelers, his duets project with Blade.

But it was Muthspiel’s appearance on the 2013 ECM album Travel Guide, a guitar trio project featuring Slava Grigoryan and Ralph Towner, that led to his own ECM debut, 2014’s Driftwood, a compelling trio project with bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Blade that found him alternating on acoustic and electric guitars.

Muthspiel followed with two quintet projects for ECM, 2016’s Rising Grace and 2018’s Where the River Goes, both featuring his core trio of Grenadier and Blade, augmented by pianist Brad Mehldau and trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire.

His latest for Manfred Eicher’s label is 2020’s Angular Blues, a trio project with former Jim Hall bassist Scott Colley and Blade, appearing on his eighth recording with the guitarist.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Recorded in Tokyo’s Studio Dede after a three-night run at the city’s Cotton Club, the pristine-sounding album was mixed with Eicher in the South of France at Studios La Buissonne.

Your earliest recordings showed a distinct Pat Metheny influence in your guitar tone and the lines you played. That was probably inescapable at the time.

Well, I wouldn’t say inescapable, but it was so magnetic. Pat was the biggest influence for me in the beginning as an electric guitar player. I did not transcribe one bar of Pat, but I sounded like him.

When I first came to Boston in ’84 to study at the New England Conservatory, in my first lesson with Mick Goodrick he said only one sentence to me: “You sound exactly like Pat.” He saw it, and it had to be addressed. A teacher sometimes has to tell the truth without any sugar coating, and Mick was good at that.

About a year after I began studying with him, we started to play duo gigs around Boston. I gradually found my own thing, but my feeling for Pat never changed. He’s one of those guys that created a new way of speaking on the instrument.

On Angular Blues, you again demonstrate a kind of relaxed chemistry with drums and bass that puts a premium on space. It’s the very antithesis of some of the more frantic stuff you did back in the early ’90s on The Promise and Black and Blue.

I need to have that feedback of what a phrase did before I can go onto the next. Maybe in the past I was more interested in the most adventurous way through something, but my ideal of sound has changed over the years.

I think the main difference is that my ideal of improvisation now is to play whatever is there in the moment and nothing else.

If something weird is there in the moment, then play that. If something dense is there, then play that. And if something totally empty is there, play that. So basically, to play without a plan and without a preconceived idea.

I try to make it kind of fluid and legato, and I want to draw as little as possible attention to any technical things. I want to hear the energy and the conversation

It sounds like you’re describing a conversational approach to playing with a trio.

Definitely that. And certain sounds need a certain space in order to live, especially with a guitar. Otherwise, the guitar becomes a percussion instrument, which can be beautiful, like in flamenco.

But my ideal, the way I play electric guitar, is I try to make it kind of fluid and legato, and I want to draw as little as possible attention to any technical things. I want to hear the energy and the conversation when I listen.

On the new album, you do some very creative things with delay, like on “Kanon in 6/8 and “Solo Kanon in 5/4,” where it sounds like you’re achieving some counterpoint playing in real time.

Yes. A canon is nothing but the same voice being repeated one or two bars later. And so I figured out that, with that principle, I can write canons and play canons with the delay, as well as improvise. So “Kanon 5/4” is just one page of written music, and from that point I keep improvising, but with that canonic principle still intact.

And it takes a certain type of thinking ahead to do this, because whatever you play will be the basis of what you play on the next bar. And there’s no loop involved in these “Kanon” pieces; that’s just a regular delay on an old-school Boss digital-delay pedal that only repeats once.

• “Wondering”

• “Angular Blues”

• “Hüttengriffe"

• “Ride”

• “Kanon in 6/8”

• “Kanon in 5/4”

The opening three tracks - “Wondering,” “Angular Blues” and “Hüttengriffe” - are all played on acoustic guitar. The rest are on electric guitar. Can you describe those instruments?

The acoustic guitar is a beautiful Australian instrument made by luthier Jim Redgate. It’s a wave double-top model and has a warm sound and excellent sustain. On this instrument I play strictly with fingers, using classical technique.

There is a sound that comes from the acoustic guitar with that technique that you cannot get with a pick. And because I grew up playing with classical technique, it’s very comfortable to me.

The electric guitar is a Domenico Moffa guitar made by a super in-demand master luthier from Italy. This guitar goes through minimal standard effects - reverb, a Boss delay and a little bit of distortion from my Tonehunter pedal. And for the recording it goes into a Fender Princeton amp.

Most lines that I play on the electric are with a pick, but on certain pieces, like the standard “I Remember April,” which concludes the new album, I’m using a hybrid technique with the right hand where I’m utilizing both pick and fingers.

I always wanted to play rhythm changes on an album because I kind of dealt with that thing forever in school

The tune “Ride” is an up-tempo number where Brian switches from brushes to sticks and brings swing energy to the table.

Yeah, it’s really like a rhythm-changes tune. I always wanted to play rhythm changes on an album because I kind of dealt with that thing forever in school. And I must say that to play that type of music as a European who grew up more with Mozart than jazz standards, this is like heaven.

This is not the first music for me; this is the second music, a second language. And I made a long journey to get to that other music. That’s why I went to the States and studied this music at New England Conservatory and Berklee.

So to play rhythm changes with Brian Blade and Scott Colley, it’s like a private high that I have when I play that music with those guys.

Your two prior ECM albums were quintet outings. With Angular Blues you return to the trio setting of 2014’s Driftwood. Any reason for going back to trio?

It feels like home. My first band, after the duo I had with my brother [trombonist Christian Muthspiel] from childhood on, was a trio, and some of the records that influenced me as I was discovering jazz were trio records. So trio was sort of the core discipline for me. Also, the fact that I can steer so much harmonically in a trio is kind of attractive to me.

- Pick up Wolfgang Muthspiel's Angular Blues on Amazon.

Bill Milkowski's first piece for Guitar Player was a profile on fellow Milwaukee native Daryl Stuermer, which appeared in the September 1976 issue. Over the decades he contributed numerous pieces to GP while also freelancing for various other music magazines. Bill is the author of biographies on Jaco Pastorius, Pat Martino, Keith Richards and Michael Brecker. He received the Jazz Journalist Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 and was a 2015 recipient of the Montreal Jazz Festival's Bruce Lundvall Award presented to a non-musician who has made an impact on the world of jazz or contributed to its development through their work in the performing arts, the recording industry or the media.