Robby Krieger and John Densmore Unmask the Myths Behind the Doors’ Final Album, 1971’s 'L.A. Woman'

50 years on, the Doors' surviving members share song secrets, memories of Jim Morrison's genius, and recall playing God with Bruce Botnick's weather machine.

Myths and mystery pervade nearly everything about the Doors. But at the heart of those myths are real people. And real people are never one-dimensional, are they? The same may be said about the Doors as a collective, and perhaps even more so, as individual men.

Transmuting mythology and erotic intrigue into the raw material for a blues-based, jazz-conscious, and soul-savvy sound, the Doors distilled an unlikely alchemy of confrontational, cutting-edge pop-rock, experimental theater, and potent poetry.

That volatile chemistry would explode into public consciousness less than two years after their auspicious first rehearsals by the warm sands of Venice Beach, California, in the early summer of 1965.

The mythological motifs, militant stance, and nods to both classical and avant-garde theater that singer Jim Morrison weaponized as broadswords in the culture wars of the late ’60s were quickly met by a quadruple counterpunch of adulation, controversy, commercial success and, finally, legal jeopardy following his arrest in Miami, Florida on March 1, 1969, on questionable charges of public obscenity and inciting a riot.

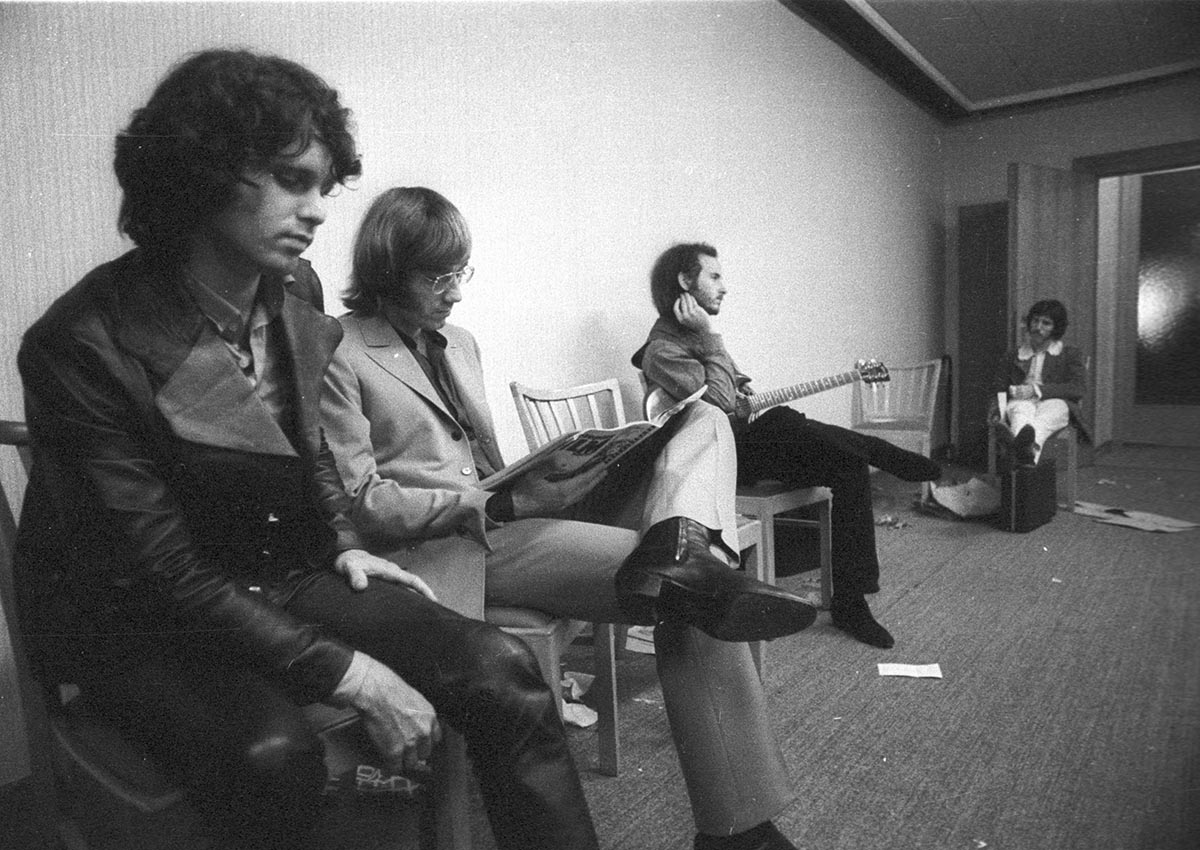

Rocked by the harsh reaction and rejection from promoters and the public, Morrison and his bandmates – late keyboardist Ray Manzarek, drummer John Densmore, and their quietly virtuosic guitarist and co-songwriter Robby Krieger – collected themselves and carried on doing what they loved most: making music together as a team. Strained synapses and all.

In the last few turbulent years of his life, then, Morrison helped the Doors deliver two arresting and accomplished albums, boasting a clutch of enduring staples of rock radio, including Morrison Hotel’s barreling “Roadhouse Blues,” as well as L.A. Woman’s “Riders on the Storm,” “Love Her Madly,” and the indelible title track, a seven-minute post-modern blues-noir epic for the ages.

L.A. Woman, the album that began to bloom only when the band’s longtime star producer, Paul Rothchild, quit the project in evident disgust in its formative stages, turns 50 this year. It is a bittersweet anniversary.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

With leading-edge audio tools wielded by album producer/engineer Bruce Botnick, and the help of realignment technology from Plangent Processes, the upcoming 176kHz/24-bit remasters of the L.A. Woman 50th Anniversary Deluxe Edition have been restored to their proper “true azimuth” tape speed.

The tracks sound as vivid, immediate, and urgent as they must have sounded during first playback through the Langevin 12-input solid-state console at the Doors Workshop studio at 8512 Santa Monica Boulevard, in West Hollywood.

To be fair, it was a makeshift studio at best: a high-ceilinged but compact room with a few baffles, a couple of acoustic wall panels, and few frills – except for plenty of cold bottled beer.

Critical and commercial redemption for the Doors would not be long in coming, though sadly Morrison would not be there to bask in it. Jim Morrison died in the Le Marais district of Paris on July 3, 1971. He was 27 years old.

Fifty years later, the group’s critics and fans are still trying to sort it all out: The music. The mercurial manic-to-morose performances. The self-medication. The madness. The militancy. The mellifluous-to-murderous vocal timbres. The majesty and agony of it all. And yes, the mystery of Jim’s untimely passing, for which these pages are not the suitable venue for speculation or surmise.

All told, while they may have just been four bright college-aged kids with a taste for mischief, Mary Jane, and music, the Doors, it seems, were simply too much mind expansion for the 20th century to mentally manage.

So it was all conveniently converted into myth. How do you unravel a myth? Let’s start with music. It’s proven good for a lot of things.

Do It, Robby, Do It

Of all the band’s enigmas, their taciturn and unflappable guitarist, 75-year-old Robert Alan Krieger, remains the least unraveled, in no small part because he’s the only surviving member not to have written a memoir – yet. (“I saw what happened when the other guys published theirs,” he says. “Nothing but trouble.”)

That will change this November, when Little, Brown is set to publish Krieger’s long-awaited biography, Set the Night on Fire.

Krieger is easily among the most underestimated guitar players in the pantheon of 1960s rock. His distinctive playing synthesizes ideas from a galactic range of artists: flamenco master Sabicas, jazz titan Wes Montgomery, blues great Mike Bloomfield, the Ventures’ Nokie Edwards, Indian sitar icon Ravi Shankar, the great Chuck Berry and, notably, the early ’60s folk and blues revival.

What’s more, Krieger wrote the lion’s share of the Doors’ major hits, both the music and the words, including “Touch Me,” “Light My Fire,” “Love Me Two Times,” and “Love Her Madly.”

“Robby was so incredibly gifted, from his playing to his songwriting abilities,” says Doors drummer John Densmore, whose own most recent book, The Seekers: Meetings With Remarkable Musicians (And Other Artists) (Hachette Books), explores his personal connections to luminaries from Jerry Lee Lewis to his drum hero, Elvin Jones.

“Interestingly, Robby never played with a pick – he had these long fingernails on his right hand from playing flamenco, so when he’d take a solo or play a riff, he would play it with his fingers. They’d sort of crawl across the strings like a crab. It gave him this very unique, liquid style, a gloriously impressionistic sound.”

All those popping, ultra-present pentatonic riffs like “Break On Through,” “Love Me Two Times,” “Maggie M’Gill,” and the iconic E-blues figures on “Roadhouse Blues”? Every single one of them was played with the fingers of Krieger’s right hand, a clawhammer-like thumb-index-middle talon technique that included clacking the pickups (“The WASP”) raking 6th, 9th, and major-seventh chords flamenco-style (“Love Her Madly”), beautifully bastardizing banjo rolls (“Do It”), and popping drop-tuned octaves up and down the neck in a funk-bass fashion (“Land Ho!”). And that’s all before one gets to his singular slide guitar technique.

Honestly, I only stole guitar ideas to write songs out of them, never to copy someone else’s playing style. The only exception to that might be Duane Allman

Robby Krieger

In addition to the floored fuzz majesty of “When the Music’s Over,” “The Changeling,” and “Hello, I Love You,” Krieger also played buckets of slinky clean rhythmic parts, what Densmore calls his “liquid style” of arpeggiating chords and coaxing clean lead lines. His blues-via-Bombay slide work even predates the great Duane Allman, who wouldn’t pick up a Coricidin bottle until November 1968.

That’s ironic, as Krieger confesses that Allman’s slide playing was the one technique from another player he’d be determined to cop. With the help of Rothchild and Botnick, Krieger stacked guitar harmonies and orchestrated his parts in the studio in a manner not unlike his contemporary Jimmy Page, and his parts would impact countless ’80s luminaries like Echo & the Bunnymen, Depeche Mode, Nick Cave, and Siouxsie & the Banshees.

My Fingers Would Explore

Think about the players you know who are really attentive to playing clear, concise, and nuanced parts that never step on the vocal, always ornament and nod to the chord tones, and deliver an unmistakable mood.

Well, Krieger is one of that style’s mythical beasts. His deft right hand and vocabulary of extended chords and blues figures dilate around Morrison’s delivery, play off of Ray Manzarek’s Otis Spann–inspired Vox Continental figures, and dance with flamenco fire over Densmore’s drums.

Check out the deep cut “The Spy” from Morrison Hotel, for example, a song that foreshadows Jimmy Wilsey’s surfy work with Chris Isaak by a good 20 years. In the signature lick, Krieger outlines a descending E-minor triad on the 12th fret, leading with the B-string high B, then plucking the high E-string harmonic at the 12th fret before dropping down to the high open-E and hammering the 3rd-fret G with a slight bend.

It’s wonderfully sly, and delivered with a textbook Fender Twin Reverb clean sound, with just a touch of the Twin’s built-in vibrato and spring reverb – half surf, half rockabilly, all Krieger. Sort of.

“I actually stole that lick from a Danny Kalb song, ‘Hello Baby Blues,’ on a 1964 album called The Blues Project,” Krieger explains, “not to be confused with the group of the same name – though that’s where Danny Kalb and the guys in the Blues Project actually took their name.

"It was an Elektra album that our producer Paul Rothchild had put together a few years before we came along, with all these different blues guys – mostly white blues guys like Spider John Koerner, Tony Glover, and Geoff Muldaur.”

In fact, explains Krieger, it’s that album’s “Southbound Train” by Koerner that provided the inspiration for Krieger main verse lick on the hit “Love Me Two Times,” from 1967’s Strange Days.

Another lick that Krieger gleaned from Rothchild and Koerner’s Blues Project LP would transmute into Morrison Hotel’s “Ship of Fools,” with Krieger borrowing Mark Spoelstra’s walking rhythm and chord sequence from Blues Project’s “She’s Gone.”

“Honestly, I only stole guitar ideas to write songs out of them,” Krieger stresses, “never to copy someone else’s playing style. The only exception to that might be Duane Allman, whose slide style I really dug. Shit, I’m giving away all my secrets here!”

It’s perhaps no great secret to reveal that during the L.A. Woman sessions, Botnick close-miked Krieger's Fender Twin Reverb with an AKG C-12A large-diaphragm microphone.

Or that Krieger played his 1968 Gibson SG Standard with two T-Top humbuckers on several of the album’s tracks, and his one-piece mahogany 1954 Gibson Les Paul Black Beauty with a P-90 in the bridge position for tracking the album’s title track.

It may be less known that Krieger swung a 1968 Gibson ES-335 12-string for the upstroke strums in A minor on “Love Her Madly,” on the ultra-chunky first-position E-blues riff to “The W.A.S.P. (Texas Radio and the Big Beat),” and on the underrated gothic folk-rock ballad “Hyacinth House.” For extra zap with his SG, he typically switched between a Maestro Fuzz and Solasound Tone Bender.

See Me Change

Let’s uncover another mystery riff, shall we? Take Krieger’s pulsing, funk-approved G power-chord riff on Morrison Hotel’s “Peace Frog.” It’s simple, right? Just a G5 power chord with a 16th-note feel, leaving out the low-E and G string, with stresses on the 1, played through a wah-wah. Boom, done.

“No. It’s not actually a wah-wah on that at all,” Krieger corrects. “I had this three-pickup Gibson SG Custom at the time, and two of the pickups were out of phase. So when I’d play them together, the out-of-phase thing sounded a lot like a parked wah. It wouldn’t even be a desirable tone for most things, but it was perfect for that song.

“It’s not a partial chord either,” the guitarist cautions. As he explains, Krieger voices the chord with a full barre, muting the G and high-E string, and, on the and of 4, playing a hammer from the open low E to the 3rd-fret G. The song’s solo springs out of a jump blues–inspired transition and launches into a marriage of Chuck Berry licks and lively chromatic runs across the neck at the 15th fret.

The solo peaks with a flurry of echoes that Krieger attributes to the Maestro Echoplex tube echo unit he had begun using at that time. Even with its brooding middle passage – “Indians scattered on dawn’s highway bleeding...” – “Peace Frog” is the Doors' homage to funk.

“Absolutely: ‘Peace Frog’ and ‘The Changeling’ are the Doors’ take on James Brown grooves,” Densmore offers. “I wasn’t literally copying Bernard Purdie or anything, but that’s definitely where our heads were at on those songs.”

On the solo to the A7#9-driven “The Changeling,” Krieger would adopt a tracking technique he’d used to great success on the monumental solo to Strange Days’ epic “When the Music’s Over”: artfully multitracking fuzz guitar parts.

This time, he’d stack guitar harmonies over the underlying Bb pedal tone, jumping between flamenco-like Dorian and Phrygian figures and even a brief major-scale moment. Changeling, indeed.

“I tracked my first solo live in the room with the guys,” he explains, “Then I just heard something in my mind, like, it would be really cool if I did this harmony and then add the next one after that.

“My thought was to introduce the harmonies at different times, so it built. Somehow, I just knew exactly how it would sound. After I recorded it all, Ray said to me, ‘Man, you’re a genius.’ Only compliment he ever gave me!”

The solo evokes some of the timbral and tonal qualities of Jeff Beck’s “Beck’s Bolero,” from 1968’s Truth, which suggests Krieger may have played it through the Solasound ToneBender he toured with, and not his original Maestro Fuzz. Either way, like Beck’s signature song, Krieger goes for majesty.

For the haunting half-step walkdowns on L.A. Woman’s “L’America,” Krieger would again turn to John Koerner’s crew for inspiration: specifically, 12-string guitarist Dave Ray’s muscular take on Leadbelly’s classic “Fannin’ Street” – from the 1964 album Lots More Blues Rags and Hollers – by Koerner, Ray & Glover.

Krieger would borrow the tune’s eerie B-Bb-F#-F bass skeleton and not much else, and he’d stretch and pull the riff beyond recognition, bolstered by a fat fuzz tone.

Manzarek and Densmore found a funereal march step behind him, and Morrison would variously double the guitar melody and spin off of it. It remains one of the band’s darkest, most angular tracks, similar in spirit to “Not to Touch the Earth” – a fragment of their live opus “Celebration of the Lizard” – recorded for 1968’s Waiting for the Sun.

Shaman's Blues

Widely acknowledged as the Doors’ bluesiest album, L.A. Woman is nevertheless not a pure blues record by any stretch, but then again, neither is Led Zeppelin IV, released the same year.

“Our blues wasn’t necessarily ‘correct’ blues, but it was our take on it,” Krieger offers. “Our version of ‘Back Door Man’ on our first album had been a pretty popular song. I’d suggested we do ‘Backdoor Man’ after hearing John Hammond Jr.’s version of it on his [1964] album Big City Blues.

"His version is nothing like Howlin’ Wolf’s original. Anyway, after the grueling sessions we’d done for The Soft Parade and Morrison Hotel, we were ready to have a little more fun in the studio, and Jim really wanted to do more blues numbers.

“So one day we said, ‘Okay, Tuesday is going to be blues day!’ Jim was real happy about that. He was all excited, and Tuesday comes around, and, ‘Oh, gee, I can’t find Jim anywhere.’ Okay, so we made it Wednesday. The plan was to do a Muddy Waters song, ‘Rock Me,’ and a John Lee Hooker song, ‘Crawlin’ King Snake,’ and I think some Jimmy Reed.”

The band also had two strong blues-based originals in progress, including “Been Down So Long,” a bellowing, medium-tempo stomp inspired by Furry Lewis’s “I Will Turn Your Money Green.” (The title and lyric was inspired by a favorite novel of Jim’s: late folk singer Richard Fariña’s Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me).

Another blues-based, drawling original is “Cars Hiss by My Window,” a drowsy homage to the stifling heat and sexual tension of Morrison’s wasted tenure in Venice Beach.

Happily, the Doors’ rehearsal space turned out to be a suitable spot to capture the band’s bluesy side at its most unvarnished, without the kind of rigor imposed by the eagle-eared if perfectionist Rothchild. “All of the Doors’ studio and live albums were recorded on eight-track, 15-ips analog. That was the most we ever had,” Botnick recalls.

“We’d recorded at Sunset Sound Recorders, TTG Studios, and the new Elektra West Studios on La Cienega Boulevard at Sunset Boulevard. The Doors’ office and rehearsal room, on the other hand, was across the street from Elektra and was really small – approximately 18 by 25.

"The guys were on top of one another, live in the room, no headphones. Jim stood in the room with the band with his microphone in hand, the same one that he used onstage, and it was split out to a Fender Twin Reverb amp so that the band could hear him.

“One positive side to Rothchild’s methods was that by the time we recorded L.A. Woman, the guys really knew how to make a record,” he says.

“They knew how to balance with one another in the room. That’s a big reason why it sounds so good. And it wasn’t terribly loud in there, because they had to be able to hear one another without headphones. And the crazy thing is, when I listen to the soloed tracks, even now, there’s almost no leakage, even in the drum microphones! And I barely had any gobos – just a few to either side of John’s drums, and that was it.”

Texas Radio

To flesh out the instrumentation for the sessions, Botnick had the good idea to ring up a young Texas-bred guitar hotshot named Marc Benno, who’d been one half of the duet Asylum Choir with boho/jazzbo songsmith Leon Russell. Earlier that year, Botnick had mixed Benno’s second solo album, Minnows, which featured Elvis Presley bassist Jerry Scheff.

The pair made for a premium package deal, and Scheff’s chair with the King was an honorific not lost on a delighted Morrison. So, one day in December 1970, Benno lugged his 1970 blackface Fender Pro Reverb and 1954 Gibson Les Paul goldtop down to the Workshop, and dialed in his go-to blues tone: bass at 3, treble at 7, reverb around 2.5, volume just under 3.

“We might have quickly gone over the chord changes to the songs, but basically, we just dove in and started jamming,” Benno recalls.

Though generally credited with rhythm guitar (which he handles expertly – check out his funky A-triad syncopations throughout “L.A.Woman”), Benno does contribute a clutch of key single-note licks.

He pegs those signature blues-box hooks with Krieger on “Been Down So Long,” and that’s Benno backing Morrison’s vocal phrasing on those classic “Mr. Mo-jo Ri-sin’” accents in “L.A. Woman”’s breakdown section, as Krieger answers with serpentine blues licks of his own.

As for the nature of the breakdown itself, Densmore cops to being the man with the naughty plan: “Jim had this cool line, ‘Mr. Mojo Risin,’ and I knew mojo was a sort of charged, sexually explicit thing from the blues. So I suggested we slow the whole tempo down and then speed it up, like building towards an orgasm. And everybody just went: ‘Okay, cool.’”

During the build-up, both Krieger and Benno begin answering the 'Mr. Mojo' invocation together, Benno attacking a classic Texas whole-tone up-bend lick (answering Morrison's higher ‘Mo-jo Ri-sin’’ yelps) on the G string in fifth-position, while, backed by Morrison’s guttural shouts, Krieger breaks out and up into his second solo, knocking out chord-specific major pentatonic bends over the following C and D7 chords, and then descending back over the main A blues groove with a touch of alternate-picked Mixolydian elegance.

All this as Benno locks down the driving rhythm machine again with Densmore, Scheff, and Manzarek. It’s exhilarating shit.

“Benno was the perfect addition to the band,” Krieger says. “We never talked about parts. He just knew exactly what to play. It was all very intuitive. Looking back on it, that was pretty cool.”

Into This World We're Thrown

The final recording of the Doors with Jim Morrison started life as an homage to Vaughn Monroe’s 1948 country hit “(Ghost) Riders in the Sky,” but the Doors’ creative nucleus would deconstruct the song’s high lonesome gallop with something far jazzier and more haunting.

Morrison’s plaintive croon would marry Monroe’s western holler with lyrical borrows from poet Hart Crane, philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, and the true crime story of homicidal hitchhiker Billy Cook.

Krieger and Manzarek, meanwhile, would lock into a smooth West Coast jazz ostinato, built around an Emin7/Emin6 tonality, with Manzarek's Fender Rhodes cascades evoking vibes master Lionel Hampton, and acting as the perfect bed for Krieger's vibrato-rich Twin Reverb tones.

With Scheff doubling Manzarek’s insistent 16th-note Emin7 bass outline, it was down to Densmore to find the nuanced touch needed to cement the song’s translucent feel.

Botnick took care of the capture, mounting two Neumann KM84 cardioid mics as overheads, another KM84 on the snare, and using the very same kick-drum mic he’d used on Densmore for songs like “Light My Fire,” “The End,” “The Unknown Soldier,” and “Moonlight Drive”: an Altec 633A “Salt Shaker.”

“‘Riders on the Storm’ is probably my favorite groove of any Doors song, along with ‘L.A. Woman,’” Densmore says. “I knew I wanted it to sound jazzy, and a few years back, I’d seen [jazz piano great] Oscar Peterson in Los Angeles. Now, Oscar’s drummer, Ed Thigpen, had these rivets in his ride cymbal. I thought, ‘That’s it – that’s my sound!’ You can hear me playing that cymbal on ‘Riders...’”

Typically, Densmore says, on a regular 4/4 groove, he’d lean toward having the snare drum hitting on two and four, with the right hand on the ride cymbal keeping the regular eighth notes. In this case, though, he started playing the eighth notes on both hands.

“Sure, I’m still accenting the two and four a bit heavier on the snare,” he clarifies, “but listen to the turnarounds – I’m keeping that eighth-note feel going on both the ride cymbal and the snare. I still don’t know exactly how or why I did it, but damn, I stumbled onto a pocket that was just bottomless.”

The top end was fairly vast, as well, an ambiance augmented by recordings of thunder and rain that Botnick had at his disposal. Credit for the idea, though, has to go to Morrison.

Listen to the hilarious outtake of Take 6 of “Riders on the Storm” from the L.A. Woman 40th Anniversary Edition, which finds Morrison goofing splendidly on the theme song from a local Albuquerque, New Mexico TV station (“K-Circle-B, the TV ranch for you and me!”). Just before the take, still in rare form, he announces, “This is called ‘Riders on the Storm,’ Take... 9.”

We had a few tape machines queued up to play individual thunderclaps, so we could drop one in whenever we wanted behind some great lick. That was a little like commanding the universe!

John Densmore

He then spontaneously imitates the sound of thunder into his mic, and says, “Hey, that’s a good idea – thunder!” To which Densmore replies, “That’d be great at the beginning.” Morrison again: “We’ll send it out to Arizona for some good thunder!”

“That was a great moment,” Densmore recalls. “And when we discovered that Bruce Botnick actually had a continual soundtrack of rain and thunder, well, I guess we got to play God a bit. We had a few tape machines queued up to play individual thunderclaps, so we could drop one in whenever we wanted behind some great lick. That was a little like commanding the universe!”

Close listening reveals Densmore adding a hypnotic conga part as an overdub. The one other overdub? Jim Morrison’s final contribution to the Doors: a whispered backing vocal take, a ghostly presence haunting each and every line, and each and every listener who’s tuned into it since, whatever they may make of the man behind the microphone.

Cool And Slow, With Precision

“There were several things that made Jim a great singer,” Botnick says, putting the finishing touches on the extensive outtakes and alternate versions that will accompany the expanded and remastered L.A. Woman 50th Anniversary collection.

“One, Jim Morrison was able to become whatever song he was singing. He became that character. He was very, very good at it. Secondly, in terms of mic technique, Jim Morrison was one of the very best singers I’ve ever recorded. He intuitively knew how to work a microphone, much like Frank Sinatra did. Jim really admired Sinatra’s sound and phrasing.

“If he was screaming his vocals in the studio,” Botnick continues, “he also knew how to back off the microphone correctly and then move in for a soft passage. Jim basically self-leveled himself. Third, he just had a really great vocal range and tonality.”

Yup. Go ahead, give it a try. Oh, you’ll do fine on all the crooning baritone parts, sure, but when Morrison starts ripping all those high A and Bb notes (use your high E-string 5th and 6th frets for reference) in full-volume chest voice, well, that’s where the hitchhiker meets the highway.

Even during the L.A. Woman sessions, when conventional wisdom has it that Morrison’s voice had lost some of its steam, he could still hit an absolutely blood-curdling high Bb on the outro to “The Changeling”: “See me CHAAAANGE!”

When the more velvety, Sinatra-style tones were required, you get the persona at the heart of “Riders on the Storm,” in which Morrison's timbres gently ride the contours of an EMT-140 plate reverb, the same type of reverb Botnick had used on his voice four years earlier, in their very first studio outing on songs like “The End” and “Crystal Ship” from their debut album.

Interestingly, the L.A. Woman sessions were the first time Jim had used his handheld Electro-Voice 676G stage mic for recording his vocals. Botnick had previously set him up in an acoustic hut or isolation booth, with either a Neumann U47, Neumann U67, or AKG C12A, typically shock-mounted.

“Jim always recorded live vocal takes with the band,” Botnick stresses. “It was very rare that we’d have to redo a vocal after we got our best take.” Krieger concurs:

“It’s strange, because when we started, Jim almost sounded like a kid, which I guess we all were, in a way. But it wasn’t long before he became the most amazing singer. I’ve heard a lot of guys try to sing like Jim Morrison, but his power, pitch, and range were pretty unbeatable.”

Even through the toughest of his literal trials and tribulations, with the law and with own demons increasingly on his trail, when it came to the studio, Jim Morrison – unpredictable and maddening as he could be – always delivered in the end.

Fifty years later, the music speaks for itself, and if you listen deeply to the studio banter from the many alternate takes and unreleased tracks from all the 50th Anniversary editions, you still have permission to walk into the tracking room and connect with this mysterious union of four complex, creative, and curious L.A. men. Real ones. Flawed ones. You’ll still find them even in those mythical hours of magic, in a great visitation of energy within your stereo field.

“Jim told us at the very beginning,” Densmore says finally, fondly, “’I’ve got this concert in my head. I’d like you guys to help me get it out.’ I’d like to think we did that for him.”

- For more about Robby Krieger’s work with the Doors, his recent solo albums, his playing techniques, his fine-art painting, and his upcoming memoir, visit robbykrieger.com

- James Rotondi would like to thank Robby Krieger, John Densmore, Bruce Botnick, Marc Benno, Frank Lisciandro, John Logan, Jeffery Jampol, Timothy White, Jason Elzy, Michael Shrieve, Shawn Pelton, Dave Hill, Jr., Colin Poulton, Alan Paul, James R. Wilday, and Dr. Robert Levy for their help, insights, and fraternity.

A former editor at Guitar Player and Guitar World, and an ex-member of Humble Pie, Mr. Bungle and French band AIR, author James Volpe Rotondi plays guitar for the acclaimed Led Zeppelin tribute, ZOSO, which The L.A. Times has called “head and shoulders above all other Led Zeppelin tribute bands.” Find JVR on Instagram at @james.volpe.rotondi, on the web at JVRonGTR.com, and look for upcoming tour dates at zosoontour.com