“The Black Hole Sun arpeggios were unusual for me – like the right side of a piano, or fairies dancing on a pin... I thought, ‘This is not me’”: Kim Thayil on how Soundgarden persevered through personal and musical frustrations to create Superunknown

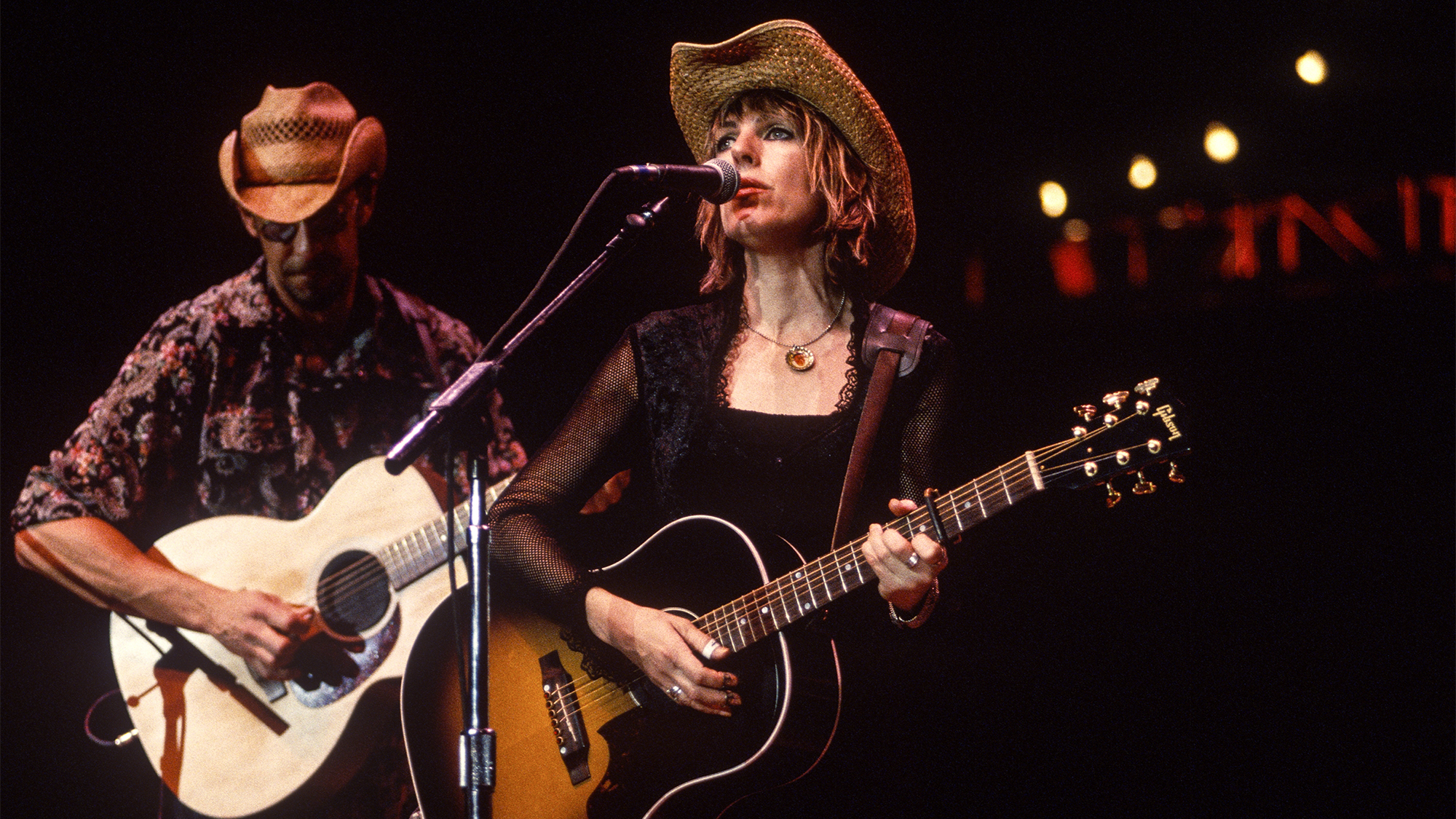

Big things were expected of Soundgarden back in 1989. The Seattle-based hard-rock quartet – then consisting of guitarist-singer Chris Cornell, lead guitarist Kim Thayil, bassist Hiro Yamamoto, and drummer Matt Cameron – were already being cited as pioneers of a new sound called “grunge,” one that blended the aesthetics of heavy metal, punk, and alternative rock.

After releasing the EPs Screaming Life and Fopp on the Sub Pop label, and a debut album, Ultramega OK, on SST, the band had signed a major-label deal with A&M Records.

But commercial success didn’t come quickly or easily for Soundgarden. Their first album for A&M, 1989’s Louder Than Love, earned glowing reviews, and college radio stations jumped on hard-driving tracks like Loud Love and Hands All Over. But, the record stalled at number 108 on Billboard, and by the time the band released their next album, 1991’s Badmotorfinger, one of their fellow Seattle bands, Alice in Chains, had gone Platinum with Facelift.

Meanwhile, two other groups from the area, Nirvana and Pearl Jam, dropped two albums – Nevermind and Ten, respectively – that exploded on the charts. The grunge revolution was now in full bloom, but Soundgarden were still awaiting their day in the sun.

“It did make you go, ‘Hey, wait a minute!,’” Thayil recalls. “You think, ‘We’ve been doing all this work, we’re touring Europe and the U.S. in vans, and then somebody else releases their first record and they’re in a bus and getting a nicer payday.’ You think that initially – these guys got signed and their record is Platinum – but then you think, ‘Well, we opened doors for ourselves and our friends, but at the same time they also opened doors for us.’ We were getting attention, and our audience was growing slowly.

“There were other bands that never had that kind of success. I’m thinking of Mudhoney, Tad and the Screaming Trees – great critical acclaim and great press, but they never had the sales.” But, Soundgarden’s day was coming, thanks to Badmotorfinger.

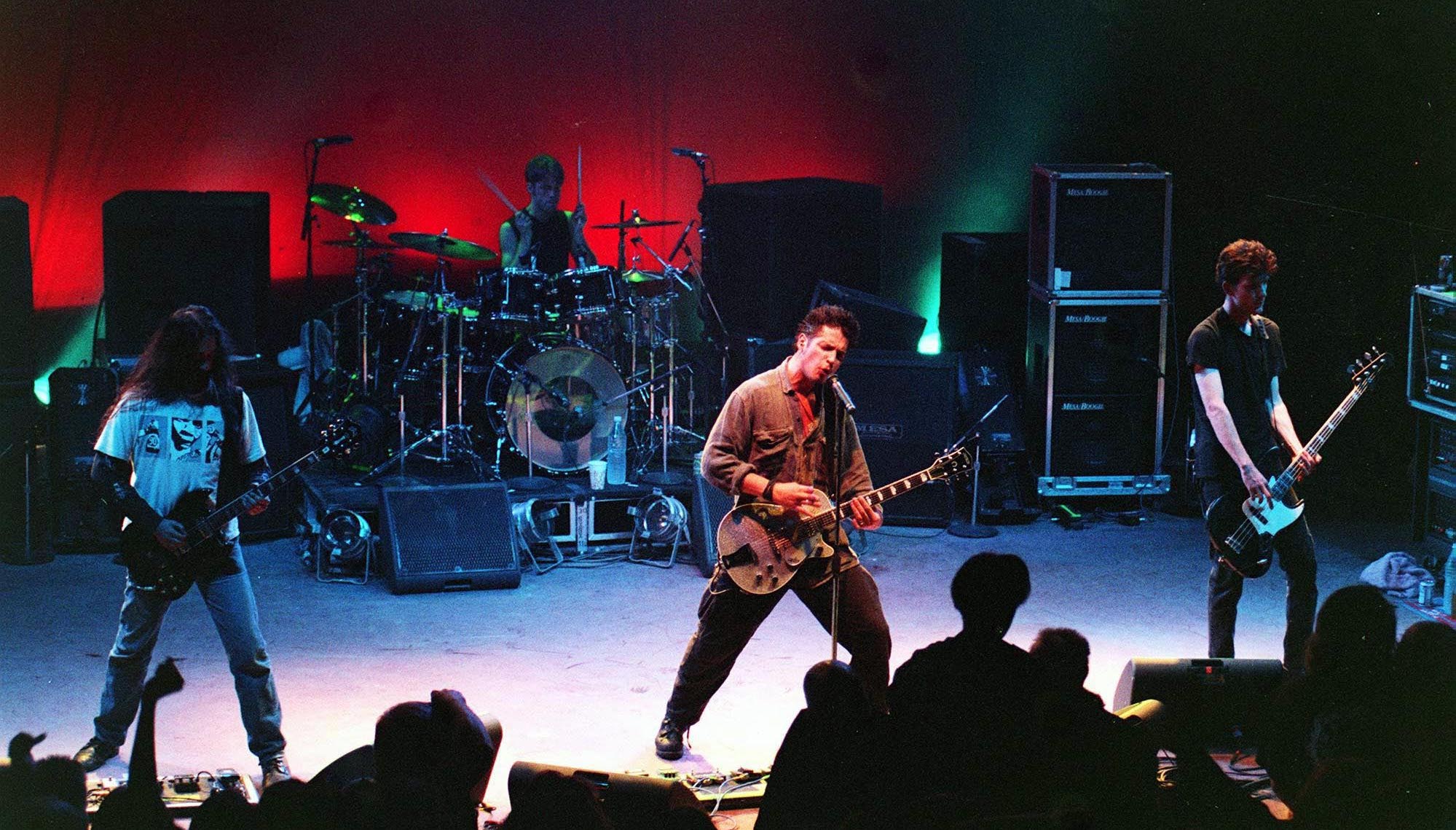

With new bassist Ben Shepherd added to the band’s ambitious songwriting team, Soundgarden’s unique blend of walloping riffs and widescreen hooks, combined with unorthodox guitar tunings and arty psychedelia, had resulted in a record packed with cuts like Outshined, Rusty Cage, and Jesus Christ Pose that ultimately won over rock and alternative radio – and perhaps more importantly, MTV.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Over the course of two years, the album sold more than a million copies (by 1996 it was certified double Platinum), and as the band toured relentlessly (at times opening for Guns N’ Roses), the stage was set for their grandest adventure: the 1994 monster, Superunknown.

Everything that was great about Soundgarden – the band’s dynamic and intuitive interplay, Thayil’s snaggle-toothed riffs and scalding solos, Cornell’s transcendent vocals (sensuous crooning one moment, epic roars the next), and the group’s rapidly maturing songcraft – which balanced far-out experimentation with sharp, pop-minded sensibilities – came together spectacularly on Superunknown.

Co-produced by the band and Michael Beinhorn, who had previously helmed hits for the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Soul Asylum, the record was a major leap forward on all levels.

Throughout its 15 tracks, the group channeled influences like the Beatles and Led Zeppelin without sacrificing punk-rock urgency or their own distinctive sound. Pummeling grinders like 4th of July, Limo Wreck and Mailman enthralled existing fans, while a fleet of turbulent, hook-filled singles – Spoonman, My Wave, Fell on Black Days, The Day I Tried to Live, and the album’s across-the-board smash, Black Hole Sun – brought in scores of new converts.

Immediately hailed as a masterpiece upon its release on March 8, 1994, Superunknown debuted at number one on the Billboard 200 album chart and went on to sell more than six million copies.

Thayil remembers being on a press tour in England when he and his bandmates first heard that Superunknown would hit number one.

“We were in an elevator, and our manager, Susan Silver, gave us the news,” he says. “We kind of looked at each other and smiled, but we didn’t fully understand what it meant. We were happy, but there were no streamers or party poppers or champagne flowing. It didn’t impact us the way it should have.”

My personal life and things involving our colleagues and peers hit their nadir, but our professional life was at its zenith with the record hitting number one and [us] being on the cover of Rolling Stone

Consuming Thayil’s thoughts was the recent breakup of a longtime personal relationship.

“We’d been together for 10 years, and it hit a point where, in spite of work over the next few months to try to retrieve and maintain the relationship, it was done,” he recalls. Making matters worse, soon after, he – along with others in the tight-knit Seattle community – would be rocked by Kurt Cobain’s suicide just one month after Superunknown’s release.

“My personal life and things involving our colleagues and peers hit their nadir,” Thayil recalls, “but our professional life was at its zenith with the record hitting number one and [us] being on the cover of Rolling Stone. I know the success should have meant something, but it didn’t budge the meter from everything sucking. I wish we could have had the experience at another time.”

Sadly, Superunknown would be Soundgarden’s high point. Its follow-up, 1996’s Down on the Upside, wasn’t as successful, and the group broke up in 1997 due to internal tensions. But today, 30 years later, Thayil looks back at Superunknown and calls it “easily among our three best albums,” alongside Badmotorfinger and Screaming Life.

“I also have no problem with people who say it’s our best album. I particularly like Superunknown, not because of its success and songs like Black Hole Sun or Spoonman, but because of its ambience and feel. It’s got everything a rock band should bring to an album, namely songwriting and performances.

“It’s not a dance record on which the producer means something. It’s not a record from the ’60s where you find some singer to actualize the songs you’ve written on piano and you find an arranger to throw other instruments in. This is a rock band, and all the work is done by the rock band.”

Superunknown is poppier and more radio friendly than the band’s previous albums. Was that by design? Did you guys have discussions in which you said, “We’ve gone this far. How can we reach the next level?”

“Never. We didn’t treat it like a video game, like, ‘We’ve knocked off all the baddies. Let’s get to the next level and find the main boss.’ We knew that growth and ascension would occur by being true to ourselves and liking what we were doing.

“It’s how we treated our live shows: If we like what we’re doing and there’s 50 people out there, the next time we come through town there will be 60 people there. We had no idea it might be a few hundred people, but we weren’t aiming for that. We liked what we did, we liked our fans, and our fans liked what we did and wanted to watch us grow. Our standard of satisfaction was based on that.”

The actual process made Superunknown one of the more difficult records we had worked on. I’m not the only one who experienced frustrations

Did you make elaborate demos of any of the material?

“Chris made some. He brought us Black Hole Sun with everything but the guitar solos. I modified a few chords to make them suspended or seventh to add a shimmer or brightness here or there, along with the guitar solos and incidental noises – what we call ‘color parts’ – to augment the ambience Michael Beinhorn created.

“I give credit to Michael for helping us define the room that the album existed in, but there was also the guy who mixed it, Brendan O’Brien, who probably got those elements in there, as well; and Jason Corsaro, the chief engineer – he was designing a lot of the mic setups and dialing in those sounds. At one point, we were talking a co-production credit for everyone, like, Soundgarden, Beinhorn, Jason Corsaro.”

Without mentioning names, did the band talk to other producers before going with Michael Beinhorn?

“We did talk to others. The record label liked the choice [of Michael Beinhorn]. They gave us a list of his records, and we thought, Wow, look at some of the people he’s worked with. The bands he worked with reached out and were like, ‘No, no, no!’ [laughs] They said, ‘Yes, he can help you make a great record, but his process is going to cause friction and difficulty within the band.’ We were told this by almost everybody we spoke to who had worked with him: ‘This is going to be problematic.’ Of course, we were like, ‘We’re us, not you.’

“We always had this kind of arrogance. We thought we were strong personalities and weren’t going to be easily bowed.

“I should clarify, I’m talking about the process, not Michael Beinhorn the person. Off the clock, I got along great with him. We’d drink overpriced Scotch and joke about books and literature. We got along great with the engineers, Jason Corsaro and Adam Kasper. But the actual process made this one of the more difficult records we had worked on. I’m not the only one who experienced frustrations.”

What exactly were those frustrations? Were they from the amount of time you spent recording?

“There’s no single point of contention, but yes, the time-consuming aspects put a stress on our playing or on our ears. You get a certain degree of fatigue from having to listen to the same thing over and over again, or by having to play the same part over and over again for a matter of hours. And it’s not as if things will always get better the more you play them; if anything, they’ll get worse because of fatigue and lack of focus.

“Sometimes that repetition wasn’t to elicit a particular performance, but rather it was to dial in a sound. That’s a ridiculous thing to do. You can record the performance and then dial it in from there or whatever. Meanwhile, you’re wasting time and causing fatigue. That said, it’s a great record, but it probably could have been made without that kind of conflict and friction.“

The Black Hole Sun arpeggios were stylistically unusual for me. I’ve described it as sounding like the right side of a piano, or little fairies dancing on the head of a pin like ballerinas. It was very delicate, and I thought, ‘This is not me’

Did Chris play more guitar on Superunknown than on previous albums?

“No. There’s some quote Beinhorn made to that effect, but no. There’s songs that Chris didn’t play on, but there’s no song that I didn’t play on. On Black Hole Sun, I played the solos, the color parts, and the chorus, but I didn’t play on the verse.“

Why was that?

“What I remember is the arpeggios. Now, I love playing arpeggios when you have delay or chorus on them, maybe some sustain or distortion. We would double them with high stringing from a 12-string guitar. [Producer] Terry Date introduced us to that on Louder Than Love.

“But the Black Hole Sun arpeggios were stylistically unusual for me. I’ve described it as sounding like the right side of a piano, or little fairies dancing on the head of a pin like ballerinas. It was very delicate, and I thought, ‘This is not me.’ Chris said, ‘You’re good at arpeggios. Go ahead and do it.’

It started psyching me out. I’d get two-thirds through and be like, ‘Argh!’ Finally, I told Chris, ‘You wrote the part – you track it!’

“I’d start to do it, but halfway through I’d fuck up. I was like, ‘All right, punch me in.’ But they said they couldn’t punch me in because I was going through a Leslie cabinet. You can’t punch in if the speaker is rotating because it’s always going to be in a different position. So it was like, ‘Kim, you have to play the whole thing straight through or else the difference in the sweep will be noticeable.’

“Every time I tried it, I would fuck up. I looked at Chris and Beinhorn and said, ‘Can’t we add the Leslie in later?’ Well, we couldn’t do that, and it started psyching me out. I’d get two-thirds through and be like, ‘Argh!’ Finally, I told Chris, ‘You wrote the part – you track it!’ I thought he would do it better than me.

“He started tracking it, and I went out in the lobby and had some tea. After 20 minutes, I went back in and looked at Chris. He shook his head and said, ‘Let’s try it again.’ In the end, he was less likely to be psyched out than me. He did the part, and I was like, ‘Whew! I’ll play on the next part.’“

Your solo on the song is fantastic – very aggressive and unpredictable.

“Thank you. It was punched in. [laughs] We partly composed that way. I learned that many of my heroes did that. You play a solo and go, ‘Take two has some better stuff going on than take one. Can we edit it?’ It’s called ‘comping.’“

Were solos your exclusive domain, or did Chris sometimes hint at what he wanted?

“On demos, he might have put in a reference thing, or he’d say if he had an idea for delay. There were cases where he’d put a particular effect on, but he’d say, ‘You can play whatever you want. It’s just for reference.’ He never pushed that. He couldn’t play lead because there were physical limitations. He had injured his wrist – I think he broke it as a kid – so he couldn’t play fast leads. But we could do twin leads. Like in the early days, on the song Little Joe – toward the end we’re both soloing. The fast funky thing is me, and the bending, droney thing is Chris.

“I liked to double-track solos. Without listening to the first one, I’d play another one blind. You’d get this serendipitous enjoyment when they matched up, and then this weird, insane chaos psychedelia when they didn’t.“

Just to clarify, you didn’t do demos of the songs you brought in?

“I just brought in songs or riffs. I’d go, ‘Here’s a part, here’s the B part.’ I committed things to memory in the early days, or I’d have a little cassette. I didn’t want to interfere with the whole process by spending time pushing buttons and hitting rewind or whatever. I was like, I’ll remember this. We’re practicing in a couple days, so I’ll just bring these things in.“

Did Ben and Matt operate the same way?

“It varied. Ben would bring in riffs, but sometimes he’d record a riff, and sometimes he’d four-track something and bring in a demo. Matt would do the same thing.

“Chris liked bringing in demos because he liked to put the song’s best foot forward. I think he thought that if he brought in a riff and I didn’t like it, then the song wouldn’t happen. But if he brought in the demo with the drums and the vocal ideas, then it was a better presentation of the song and it was more likely to be understood by the rest of us. It makes sense.

“You referred to Superunknown as being poppier, and that’s because Chris, as a singer, wrote songs that were always a little more popular. There’s something I felt since I was kid, and it was true of Aerosmith: there are Joe Perry riffs, and there are Steven Tyler riffs, which always seemed to be more vocal-friendly. Chris wrote songs that were often going to be more radio-friendly.

“We could have cool metal riffs or crazy art metal, and we could have a song that was strong and poppy and radio friendly. It would be stupid to exclude a song because it was likable. For instance, a song like Slaves and Bulldozers might not appeal to radio programmers, but it sure sounds like Soundgarden. Fell on Black Days does both.“

I was going to mention Fell on Black Days. There’s a little instrumental break that has an almost Middle Eastern or Indian flavor to it.

“That’s part of the song that Chris wrote. It’s funny because that was an important part of our identity in the early days, being primarily an Asian band, that Eastern influence and psychedelia, which the Beatles had. Chris loved the Beatles. I love the Beatles. Matt, Hiro and Ben – we were all influenced by them. That Eastern thing is present in the Beatles via George Harrison, but it’s also present in Zeppelin.

“All of us wrote that way at some point or another. It was present in all of us, and it probably came from the Beatles and Zeppelin, and maybe the fact that I’m Indian.“

You mentioned psychedelia. Parts of My Wave and Head Down have that kind of spacey feel. When you guys were recording, would you reference terms like “psychedelic”?

“We all would to various degrees. I’d say, ‘Whoa, that part sounds like the Butthole Surfers, or Zeppelin. That totally sounds like Killing Joke.’ And they’d say, ‘Yeah, it does sound like Killing Joke.’ Sometimes I would refer to a shape or color, and Ben would laugh. I communicated that way.

“Usually it was out of enthusiasm when a part was being developed through jamming or we were shown a part in a demo. We’d go, ‘That part sounds like a purple circle.’ It made people laugh, but they would get why it felt or sounded that way to us.“

Even while comping solos, were there any lead breaks on Superunknown that gave you any real trouble? Were some solos tough nuts to crack?

“Black Hole Sun was a tough one, because the song had a particular dynamic. It’s very delicate in the verses. Like I said, it’s very crystal and fragile. I can be heavy-handed with some things, but approaching that verse, which is sort of like Ann Wilson’s voice – very crystal and perfect – I couldn’t imagine doing something that would break that up.

“During the choruses, things get bigger and heavier, and they’re psychedelic. The Leslie cabinet is still there, but it’s set to a different speed for the chorus parts, so when the solo comes up, I thought, ‘Do I maintain this regard for the rotating motion of the cabinet and the delicacy of the verse?’ I re-addressed that.

“The part Chris wrote for the solo section was heavier, so I thought, ‘If I get heavy and chaotic, it will be a dynamic contrast to the verse, and that could be good. But if it loses the identity of the song, that’ll be bad.’ So it was difficult. I first tried playing psychedelic and more delicate. I tried writing a part that was more musical. It wasn’t happening and it didn’t come together, and in the end I felt like I was constraining myself.“

The unhinged solo you did play fit the song beautifully. The same can be said of the solo on 4th of July – it’s gnashing and nasty.

“That’s a song that Chris wrote. I wrote the solo, which is different from the other ways I solo. A lot of times I improvise, but in this case I actually wrote the part because it felt right. The song already had this foreboding doom because of the tuning.“

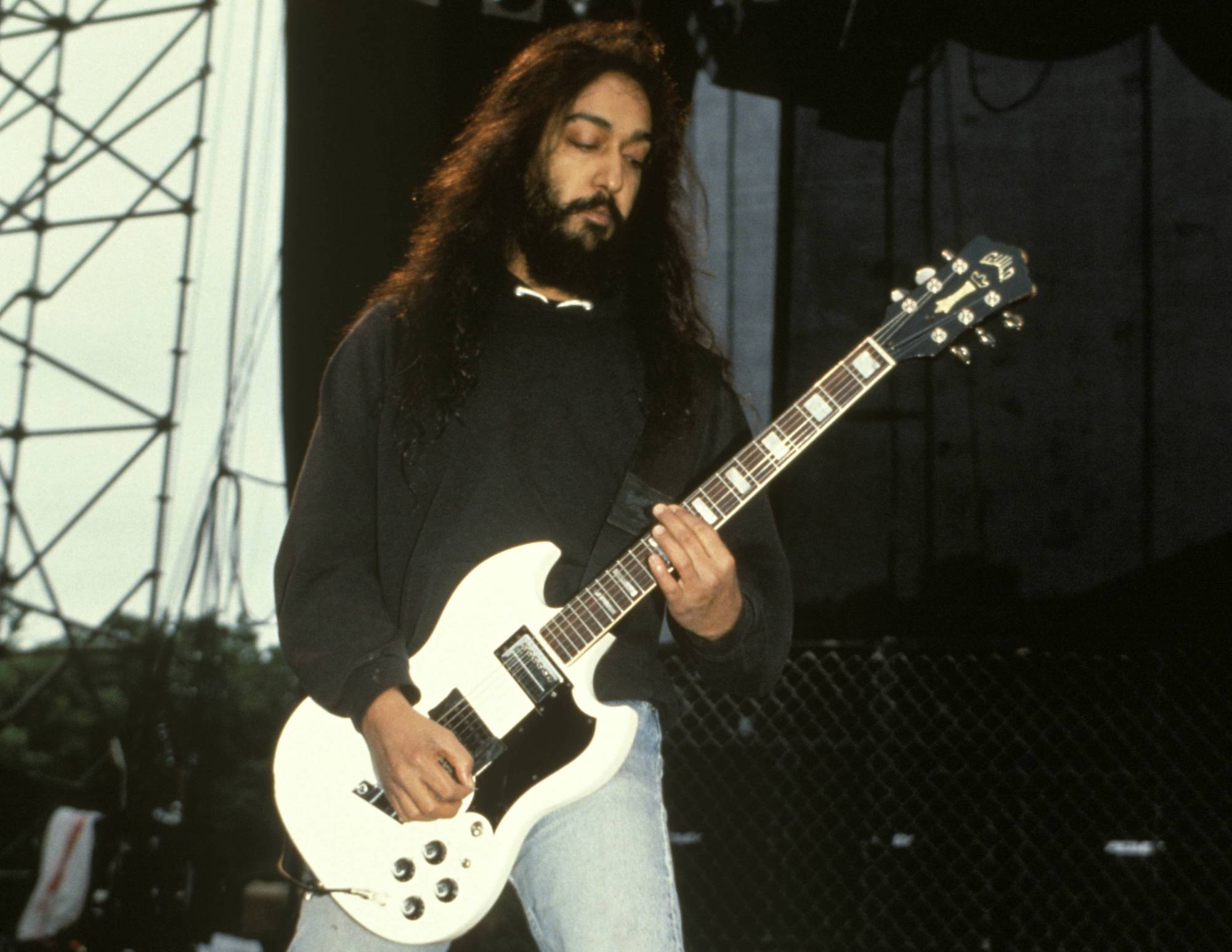

Your Guild S-100 Polara was a big part of your sound on the album.

“There were a couple of Guilds. I like them. This brings up an interesting thing about the process on Superunknown: Michael Beinhorn isn’t a guitarist; he’s a keyboardist, so in recording he’s really oriented toward sounds and tones as an engineer, rather than as a guitarist.

“If you’re trying to extract the best performance from the guitarist, that guitarist should be playing a guitar he feels comfortable with and dialing in a sound that he feels comfortable with, and then the producer and recording engineer works with that.“

You did try out other guitars on the record, though. A Tele and a Strat, right?

“I used Telecasters more on Down on the Upside. I may have tried one a little bit on Superunknown, and I might’ve tried a Strat. If I use a Telecaster, it doesn’t feel the same as the Guild, and it doesn’t stay in tune. If you remember, we’re using a lot of weird guitar tunings here.

“The Guild has stock Grover tuners, so if we’re tuning to something weird, or drop D or drop G, or if you’re playing a song for six minutes, you’re less likely to be out of tune with the Guild than with a Telecaster. Even Les Pauls would get knocked out of tune. For the odd tunings we were using, it was the best bet that we’d get the results we wanted with the Guild.“

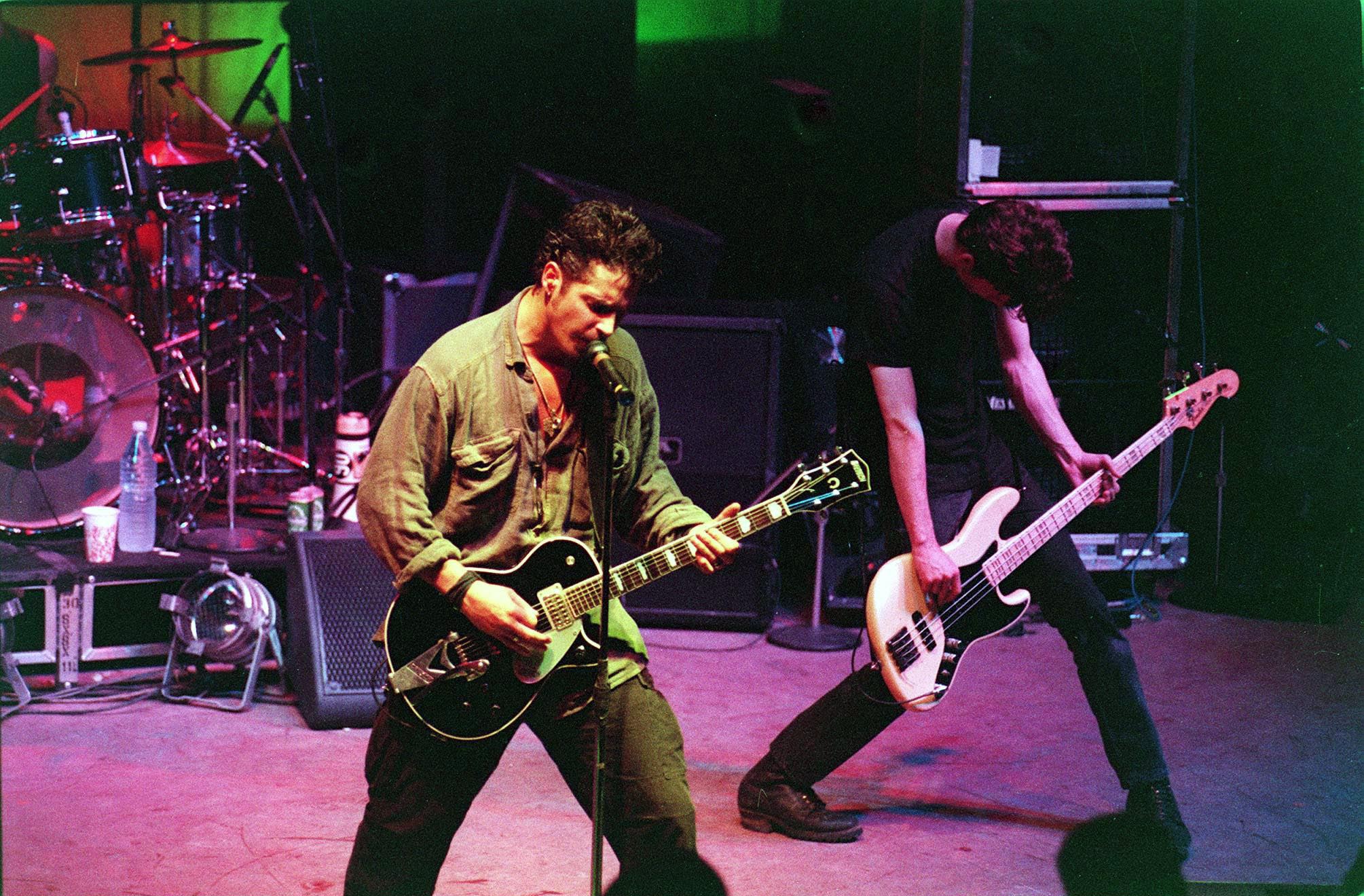

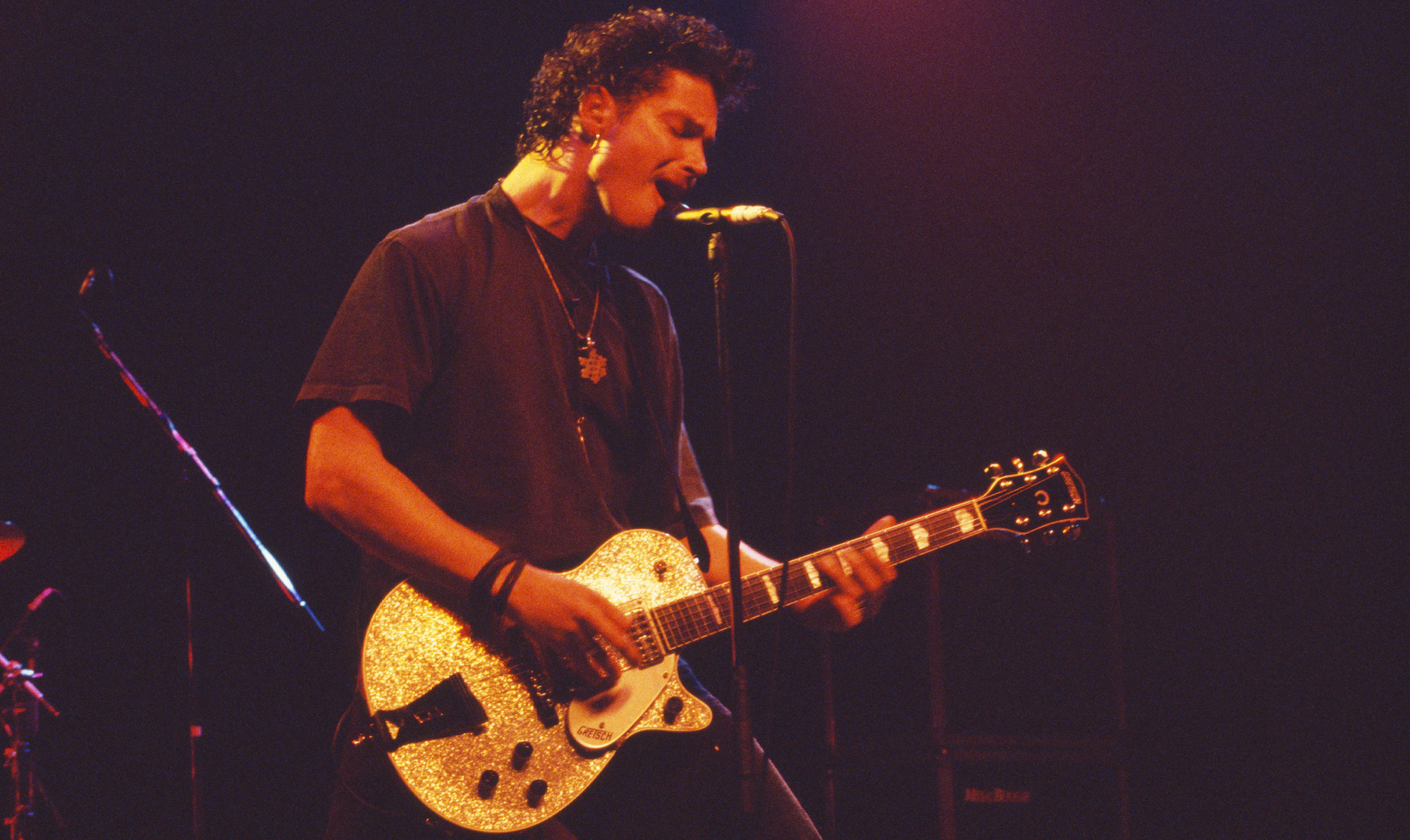

Chris used a few guitars: a Gretsch Duo Jet and a Silver Jet, along with a Fender Jazzmaster.

“Yeah, the Jazzmaster. I’m wondering whose guitar that was, if that was something Ben brought in. Everybody, even Matt, brought in guitars for us to play around with. Chris was more likely to experiment with different guitars for the sake of tone, as opposed to fingers or playing. Remember, he was our first drummer. He was oriented with playing in time and then developed his engineer ears from recording on a four-track at home with Hiro.

“He and I didn’t want to sound the same, and we had different playing styles. If he was using a Jazzmaster or a brighter-sounding guitar, it made sense for me to go to a warmer tone. If he did a warmer tone and tracked first, then I had to experiment with a brighter tone, which was not my inclination for the feel of a guitar.

“Oddly, when I would do solos, I preferred the neck pickup, the warmer pickup. But if the bed of the rhythm guitar was already warm, then your guitar has to cut through, so you go to the bridge.“

What kind of amps did you guys use on the album?

“Mesa/Boogies, perhaps. We used Peavey VTMs through Badmotorfinger, and we might have brought them in initially on Superunknown and moved on from there. I know I experimented with some Fenders, but we started using Mesa/Boogies and toured with an endorsement. There was so much playing around with fucking tones and sounds that I lost track of what amp I was using.“

Chris stopped hesitating and second-guessing himself. He just threw it out there

We talked a bit about hitting the top of the charts. But was the band prepared for the rush of mainstream success?

“Like I said, to some degree we were proud and a little bit surprised, but we were doing the work, and with each record we were getting bigger; ascending. We had no reason to believe this would not be the case here.

“Plus, I had spoken to Cliff Burnstein, one of Metallica’s managers, a year prior, at a Metallica show. He took me aside and showed me some charts about Metallica’s growth in record sales. He had some other bands on there, including us, and he showed me the pattern of our growth. He said, ‘I just want to tell you you’re sitting really nice. If you make a great next album, if you make the album of your life, it’s going to go through the roof.’

“I remembered that at practice. I said to the guys, ‘Metallica’s manager expects our next record to be huge.’ I think some of the producers we were talking to knew that, too, because there were a lot of people soliciting us, and they knew it could be big. But I think it could have happened whether we made another album with Terry Date or recorded with Michael Beinhorn or recorded with Jack Endino, as long as we made a good-sounding record and we had the songs, and we had the four guys writing.

“Chris hit his stride around Badmotorfinger and [his side project] Temple of the Dog, and he became really prolific. I think it’s precisely because he lost – we all lost – a good friend in Andy Wood from Mother Love Bone. [Wood was Mother Love Bone’s lead singer and an influential Seattle musician. Cornell conceived Temple of the Dog as a tribute to him, recruiting former Mother Love Bone guitarist Stone Gossard and bassist Jeff Ament, both of whom went on to form Pearl Jam, as well as future Pearl Jam vocalist Eddie Vedder.] Chris had a lot of regard and love for him.

“Andy’s thing was, ‘Don’t worry if your band doesn’t like it. Don’t worry if you don’t like it. Just record it. There’ll be other songs. Just keep writing.’ Chris started doing that, and he got really good. He stopped hesitating and second-guessing himself. He just threw it out there. As that went on, he started getting better at putting things together, either by not hesitating or by gaining experiences and insights, or a combination of the two. And then it was like… wow.“

You’re giving Chris high praise for his growth, but I imagine if he were here, he’d say the same about you.

“I don’t think the rest of us took that insight from Andy as readily as Chris. He told me how blown away he was by Andy’s attitude. Chris was very self-critical. I am, too. So is Hiro. There are songs Hiro wrote that are on our albums that were championed by me, or they were championed by Chris. Hiro gave up on them. But here was Andy going, ‘What the fuck?’

“Chris was enamored of that. He gave me that advice, but it was hard for me to embrace, not having the full understanding and love of the friendship of Andy Wood. I understood it intellectually, but Chris had a reverence and an emotional embrace to honor that kind of legacy and tradition.“

Kim Thayil clears up Superunknown alternate tuning misconceptions

Soundgarden had drawn attention for their use of alternate tunings prior to the release of 1994’s Superunknown. But that album saw the group take the practice to new extremes.

“We started doing these bizarre things on Badmotorfinger when Ben introduced some open tunings and slide tunings,“ Kim Thayil explains. “Then Chris did that ridiculous tuning on Mind Riot, where he tuned every string to E. That came from a comment by [Pearl Jam bassist] Jeff Ament – it was sort of a joke or a challenge, but Chris tried to see what would happen. It was brilliant. We continued that on Superunknown.“

We asked Thayil to reveal some of the more unusual tunings used on Superunknown. He was glad to share them and to clear up a few well-entrenched errors.

A lot of the tunings on the internet are wrong. It’s incredible

Which of you came up with the alternate tunings?

“That usually came from the person who came up with the main riff. Initially, our stuff was in standard tuning, and then I introduced drop D and that became our standard. For Superunknown, Limo Wreck might have had the most interesting tuning on the record: C G D G B E.“

My Wave and The Day I Tried to Live are in E E B B B B flat. Is that correct?

“No, that’s not right. For those, the last string would be E, so it’s E E B B B E. I’ve seen that incorrect online so many times. A lot of the tunings on the internet are wrong. It’s incredible.“

Glad we can clear these things up. What about the songs Head Down and Half? Do they use C G C G G E?

“That’s correct. Like Suicide had an interesting tuning – D G D G B C. Chris wrote that. It’s basically the same tuning as Birth Ritual, but when Chris was playing the arpeggiated part, he couldn’t get to the note he wanted on the high string,

so he dropped the E down to C and left it open.

“You know, if you change the tuning of your guitar, it affects how you play a certain riff or melody. It also affects how you might even strum. I mean, you’re not going to hit the guitar too hard if every string is tuned to E because you start breaking strings.“

How about the song 4th of July?

“That’s a tuning we only used once – C F C G B E. It was pretty crazy and hard to keep in tune. In order to play it live, we had to have a separate guitar that was set with heavier low strings and normal or lighter high strings.“

I imagine you guys drove your guitar techs crazy with the various tunings.

“I think they liked the challenge. It kept them on their toes.“

- For more on all things Soundgarden, visit the band's website.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.