San Francisco’s Revolutionary All-Female Band the Ace of Cups Talk Music and ‘60s Counterculture

The Summer of Love legends discuss their heroinic history and comeback.

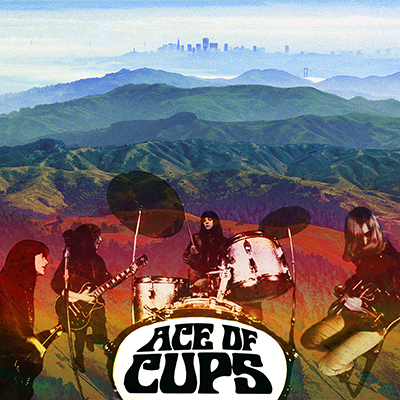

Imagine it’s the Summer of Love in San Francisco’s storied Haight-Ashbury district. Hundreds of people have spontaneously gathered in Golden Gate Park to listen, dance and vibe to a five-piece combo onstage, whose members are deftly playing a bewitching blend of rock, blues, folk and psychedelia.

Those with even a basic knowledge of rock and roll lore might rightly envision the Jefferson Airplane or the Grateful Dead as the artists at this historical cultural epicenter. But on any given afternoon, the band in question was just as likely to be the Ace of Cups, a pioneering all-female outfit that was as prominent on the scene as its more famous peers but which has, until recently, been nearly lost to history.

The Ace of Cups were formed in 1967 by guitarist/bassist/harmonica player (and graduate of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters) Denise Kaufman, lead guitarist Mary Simpson Mercy, bassist Mary Gannon, drummer Diane Vitalich and keyboardist Marla Hunt.

They divvied up vocal duties and co-wrote their own genre-bending material. They even shared stages at the Fillmore West, Winterland and the Avalon Ballroom with Jimi Hendrix (who enthusiastically name-checked them in a December 1967 Melody Maker interview), the Grateful Dead, the Band, Jefferson Airplane, Mike Bloomfield and other legends of the era.

The Ace of Cups members also contributed their talents to albums by Bloomfield and Jefferson Airplane.

Unlike many of their contemporaries, however, the Ace of Cups never inked the major-label deal that would have given them national exposure. By the early ’70s, the band had lost momentum and dissolved.

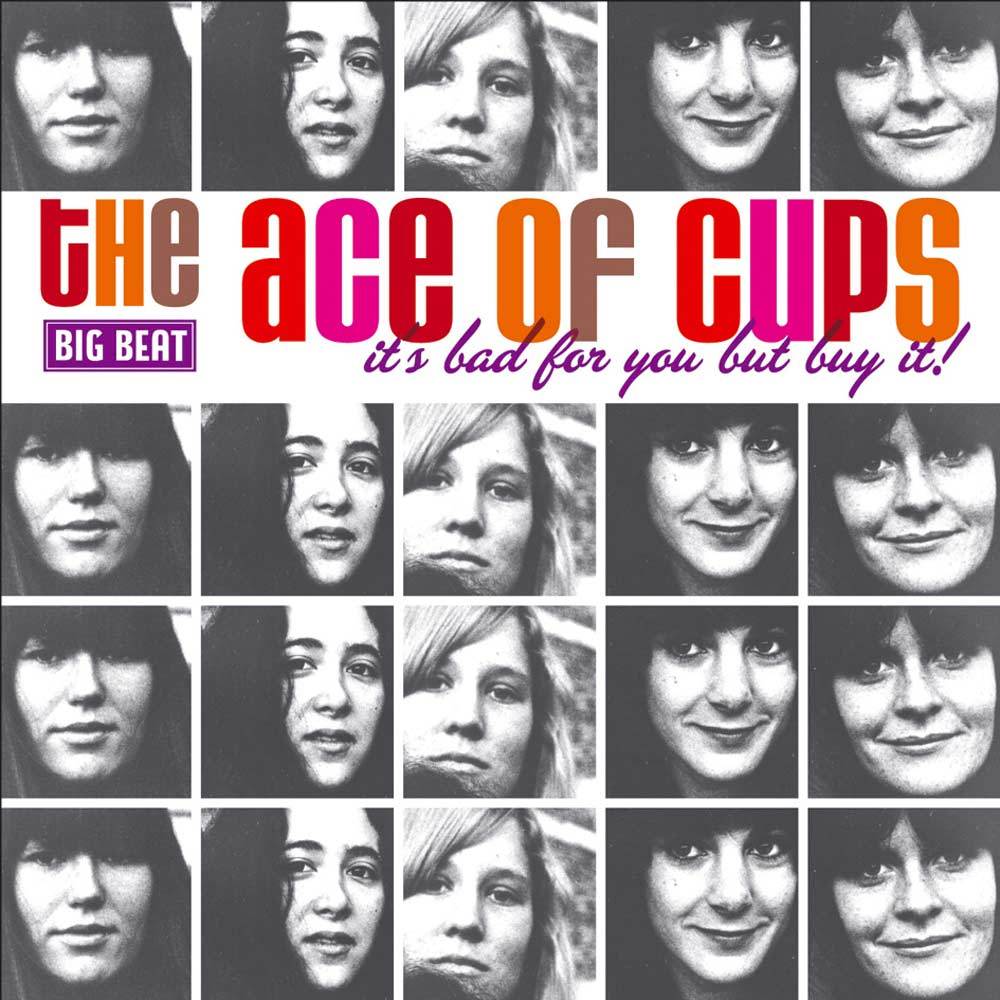

For the next several decades, its members stayed in contact with one another, but the only publicly available recordings of the Ace of Cups’ groundbreaking music were a few brief but memorable appearances in the documentaries West Pole and Revolution and the posthumously released It’s Bad for You But Buy It! (Ace Records), a 2003 compilation CD of their various recordings.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Fast-forward to summer 2017, the Summer of Love’s golden anniversary, when Kaufman, Simpson Mercy, Gannon and Vitalich were asked to reunite for the 75th birthday celebration of legendary peace activist Wavy Gravy. “We made a concerted effort to rehearse and get a set together,” Simpson Mercy explains. “While listening to us perform, George Wallace, the owner of High Moon Records, decided he wanted to give us the opportunity to make our first proper album, so we subsequently held practices for a few months and then began recording with producer Dan Shea. Our goal was to recall the spirit of the ’60s, but with a modern flair.”

Adds Kaufman, “High Moon was primarily a reissue label. The bands that they worked with had a cache of unreleased or out-of-print material. We had never really been in the studio before, so it was a huge step for them to back our album of all-new recordings.”

Enthusiasts of late-’60s psychedelic pop and folk will no doubt marvel at the stylistic rainbow of colors presented on the band’s first official release, a double-CD titled simply Ace of Cups. “Feel Good,” the album’s driving “Steppin’ Stone”-ish opener, was a lost song rescued from a 1969 bootleg that a fan had recently sent to the band after connecting with them online.

Simpson Mercy’s “Pretty Boy,” a tune originally inspired by guitarist Dickie Peterson of the band Blue Cheer, was given a new chorus and a chugging Lennon-esque feel. The Kaufman-penned “Simplicity” has a half-step descending bass under an A minor triad that sounds remarkably similar to Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven,” yet it was written several years before that song and is set over a lilting 6/8 rhythm. The haunting “Macushla/Thelina” draws from traditional Irish folk music, while the acoustic guitar-driven “We Can’t Go Back Again” is centered around an unusual tuning (low to high, C F B E G B).

After a brief tutorial, I grabbed a glass bottleneck and tracked the melody line.

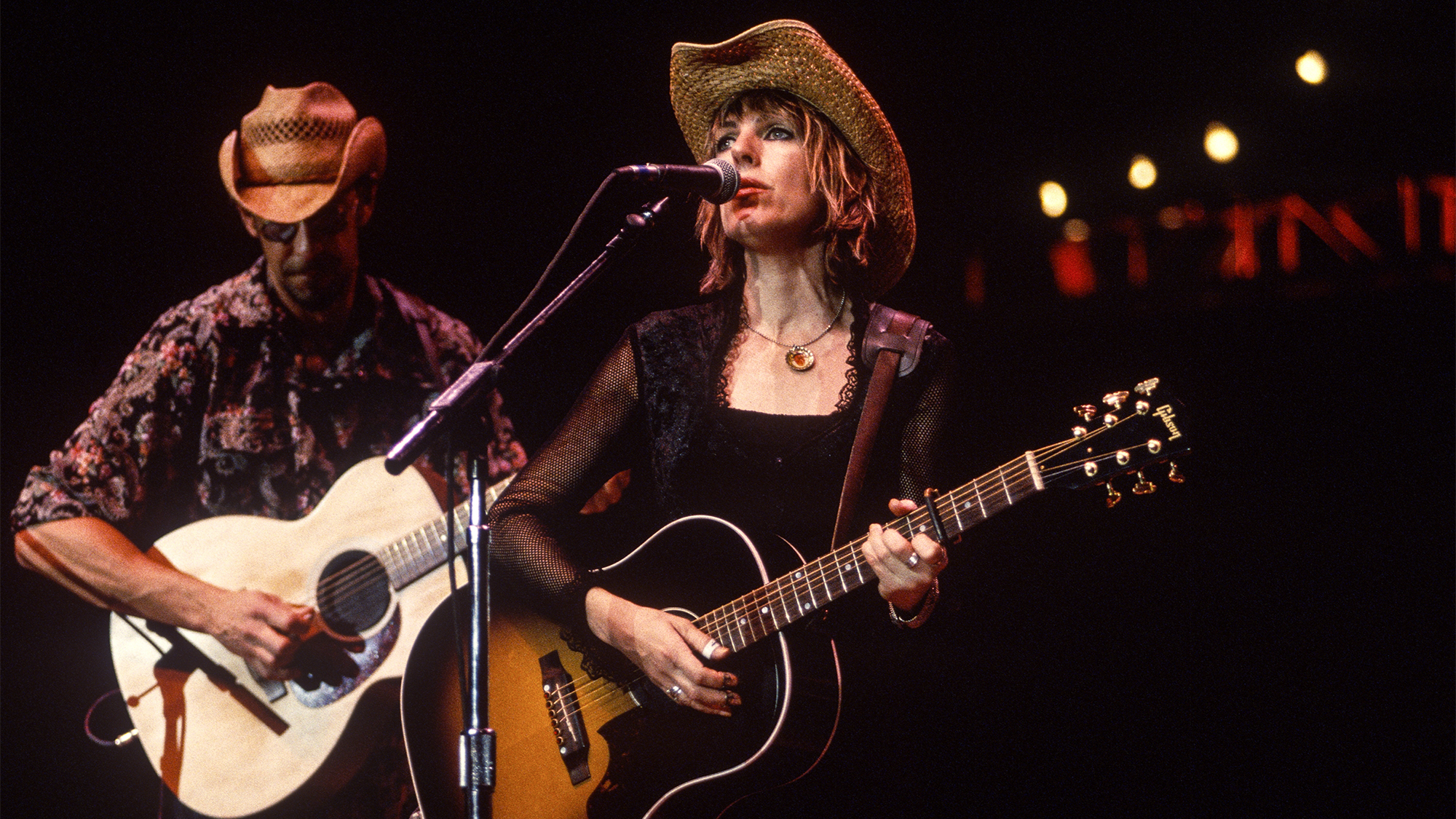

Mary Simpson Mercy

Simpson Mercy credits Shea with fostering an atmosphere of creativity and spontaneity throughout the recording process. “For ‘A Taste of One,’ he wanted me to add a slide guitar part,” she explains. “That’s something I’d never done before, but after a brief tutorial, I grabbed a glass bottleneck and tracked the melody line you hear during the song’s break.”

To record Ace of Cups, Simpson Mercy relied on an arsenal of electric guitars, including Fender Stratocasters and Telecasters, a Gibson ES-330 for the solo on “Pretty Boy,” a Rickenbacker 12-string for “Fantasy 1&4” and “Feel It in the Air” and a Guild F212 12-string acoustic guitar for “The Hermit.”

Kaufman brought her trusted flatwound-strung ’79 Music Man bass into the sessions but also found herself drawn to the more aggressive sound of the studio’s vintage Telecaster bass, an instrument that once belonged to Green Day’s Mike Dirnt. Originally the band’s rhythm guitarist, Kaufman had studied bass at Musician’s Institute in the early ’80s and wound up tracking many of the bass parts on Ace of Cups when Gannon wasn’t able to make frequent trips from her home in Hawaii.

“Listening back to our old practice and live tapes, I realized how solidly [Gannon] had nailed it,” Kaufman says. “Much of what I’m playing on the record is simply my attempt to cop the lines she originally created.”

You have to understand what a grey and restrictive time the ’50s were in order to grasp how important it was to break all of that open.

Denise Kaufman

Despite their lack of mainstream recognition, the Ace of Cups are well-respected among their musical peers. Consider the abundance of notable guest spots on their debut from musicians who played alongside them in their heyday. These include the Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir, who lends his vocal and guitar skills to the newly written song “The Well,” and blues/folk legend Taj Mahal, who contributes vocals and banjo to “Life in Your Hands” and “Interlude: Daydreamin’.” Jefferson Airplane/Hot Tuna bassist Jack Casady enlivens “Feel Good,” “On the Road” and “We Can’t Go Back Again” with his driving low end, and his bandmate guitarist Jorma Kaukonen swaps lead lines with Simpson Mercy on “Simplicity.”

Simpson Mercy and Kaufman credit their time at the forefront of San Fransisco’s counterculture movement with expanding their artistic and personal horizons. “It was a deep exploration of community and freedom, where you were allowed to experiment with the breaking of social norms without judgement or condemnation,” Kaufman explains. “You have to understand what a grey and restrictive time the ’50s were in order to grasp how important it was to break all of that open and give permission to people to exist outside of heretofore established social restrictions in the ’60s.

“We were lucky to be part of a culture where no one was going to tell you your music, your poetry, your clothes or your ideas in general were too weird and shouldn’t be that way.” Simpson Mercy concurs. “At the time we were going through it, it just felt like life,” she says. “It was only in hindsight I realized how significant an experience it actually was.”

It wasn’t necessarily what we were playing, but it was just the fact that we were playing that resonated with people.

Denise Kaufman

When considering their impact as a pioneering all-female band, Kaufman concludes, “All through our lives, there’s always been someone somewhere who has come up to us and said, ‘I saw your band when I was little and I made my mom go out and get me a guitar,’ or a saxophone, or some variation of that. It wasn’t necessarily what we were playing, but it was just the fact that we were playing that resonated with people. I believe that, now, more than ever, it’s important for all marginalized groups to have the opportunity to see themselves genuinely reflected in all aspects of our culture.”

Buy Ace of Cups debut album and Sing Your Dreams here.