“Study Is a Big Word. I Just Looked at the Charts and Saw New Chords”: Peter One Reveals His Approach to Guitar Playing and Talks Returning to Music With an Intoxicating Solo Debut, ‘Come Back to Me’

“African music is sometimes weird; the beat is difficult. So I said to myself, If I play an instrument like guitar, I’ll probably get it,” says the former West African star

Second chances in music don’t come often, but Nashville-based singer-songwriter Peter One is living proof that lightning can strike twice. In the 1980s, in the West African country of Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), One ascended to fame playing music inspired by regional Afrobeat artists, folk luminaries such as Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, and classic country singers like Don Williams.

Along with his collaborator, Jess Sah Bi, One played to thousands of fans at soccer stadiums and festivals, and entertained several presidents of African nations. In 1990, the duo’s song “African Chant” soundtracked media coverage of anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela’s release from a South African prison.

Unfortunately, politics soon played an unwelcome role in One’s decades-long exile from the music business. Later that same year, he founded the first musician’s union in Côte d’Ivoire, while pro-democracy protests broke out across the country. When One became a political target, he decided to try his luck across the Atlantic Ocean.

One landed in New York City, then bounced around a few other places, never quite finding the musical kinship he sought. Unable to restart his music career, despite the success he once enjoyed at home, he eventually settled into a quiet American life, working as a nurse in the decidedly unglamorous world of healthcare.

The story hadn’t been all that different in Côte d’Ivoire, though. Despite the fame he had achieved, One knew success wasn’t sustainable there. “At that time, musicians were not really living from music,” he says. “That’s one of the reasons why I focused on my own schooling – to have a good job, to have a career while I was doing music.”

But Nashville turned out to be the perfect place for him. That’s where he was in 2017 when a message from a record company named Awesome Tapes From Africa put One back in the game. The label, which introduces African artists and music to Western audiences, reissued Our Garden Needs Its Flowers, his 1985 album with Bi, and simultaneously resurrected his career.

One was more than prepared to return to the stage. During his sabbatical, he had continued to write and record original music, amassing somewhere around 100 songs he tracked at home using various DAWs. “Every time I was upgrading my studio, I was recording songs,” he says, “making my songs better, even re-recording the same song and bringing up the new songs.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The years he spent woodshedding without an audience gave One an endless horizon to continue writing music, rearranging and perfecting it for the opportunity he always felt would come. Come Back to Me, his debut solo album, released this May, bears the fruits of all that thankless labor, as well as his trilingual singing, which alternates from English to French to Guro, a language spoken in parts of his native Côte d’Ivoire.

“Cherie Vico” and “Kavudu” introduce One’s thumb-and-forefinger fingerpicking style and West African sense of rhythm right out of the gate. On “Staring at the Blues,” one of only a few cuts to feature traditional Western drums, he channels a mid-’70s Rolling Stones vibe, while pedal-steel guitar accentuates his melodies on “Sweet Rainbow.”

He lays back for a shuffle feel on “La Petite,” while his frailing style of strumming drives the song forward. One’s blend of musical influences from around the world, rich in harmonies and organic tones, and decorated with tastefully restrained Nashville licks, makes Come Back to Me an intoxicating, even exotic, listening experience.

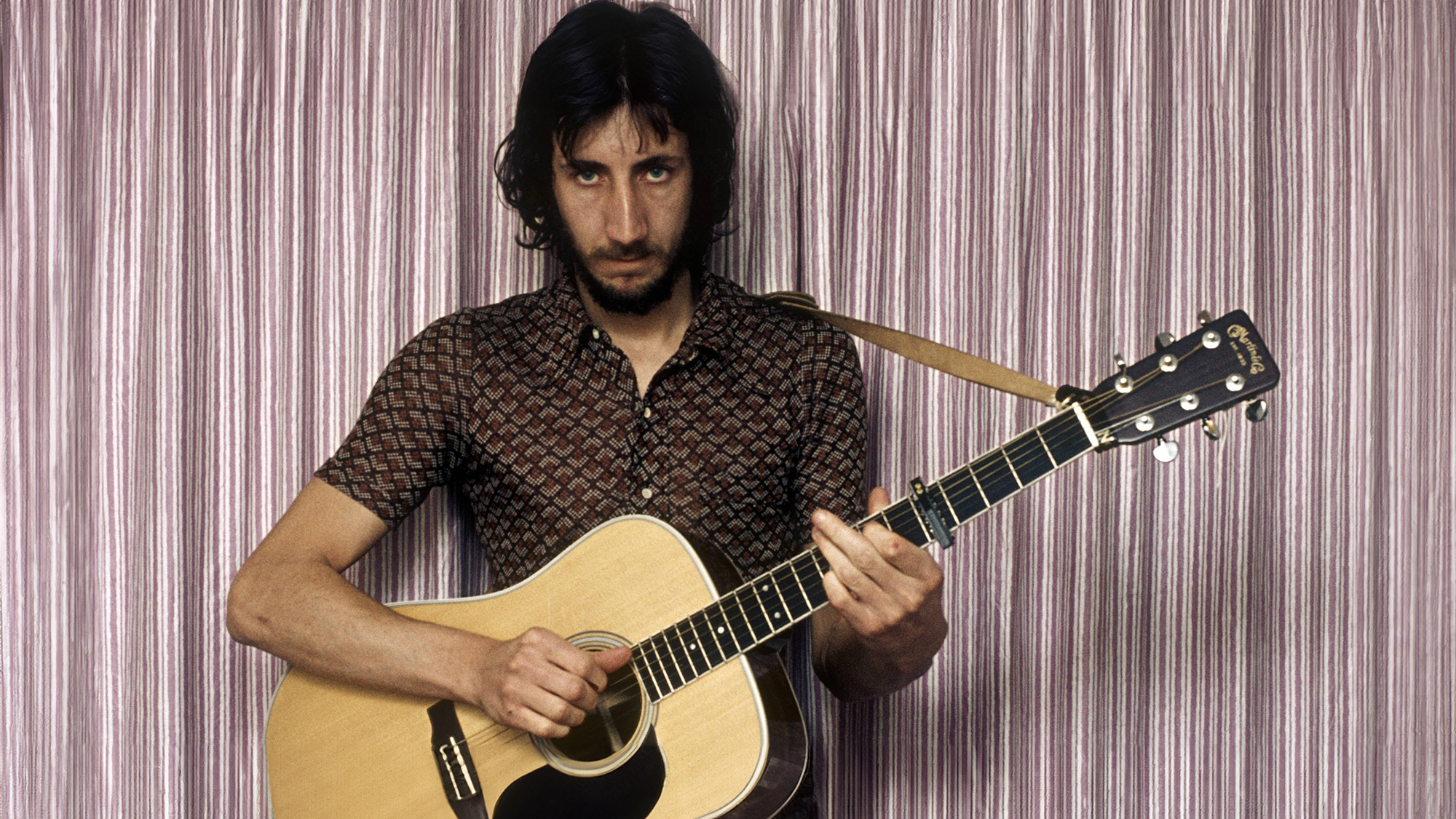

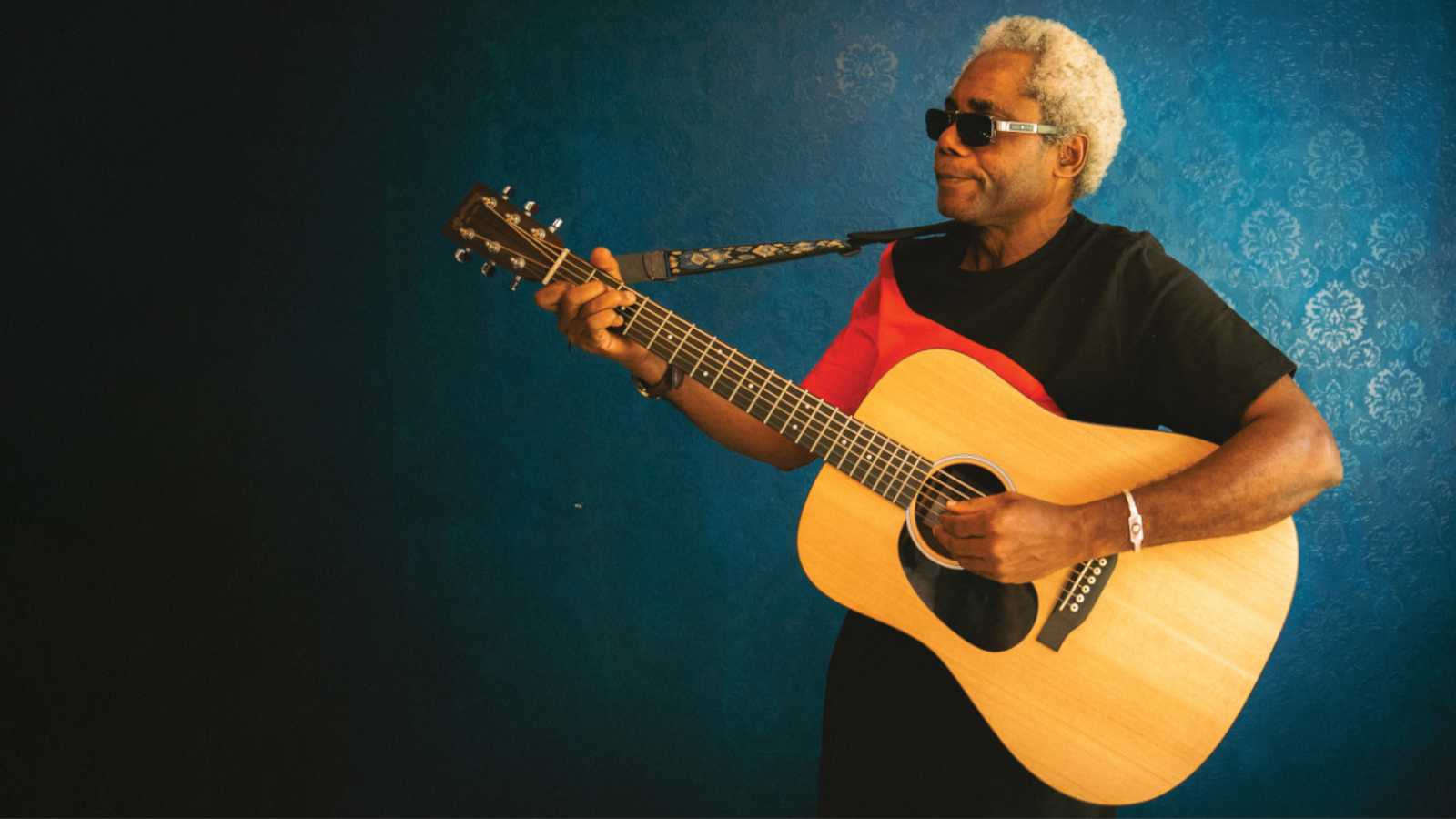

While he has traded the right-handed Yamaha acoustic guitar (re-strung for a leftie) which he played during his 1980s high point, One now strums Martin and Ibanez acoustics in front of a six-piece backing band. On the rare occasions he goes electric, he plugs a Fender Squier into a Line 6 Helix and runs direct to the soundboard.

One spoke with Guitar Player about the music that inspired him in West Africa, his relationship to his instrument, and his return to music.

When you arrived in the U.S. in the 1990s, was it heartbreaking to realize you weren’t going to be able to support yourself by playing music?

It was a little bit hard, but I was still hoping and I was still learning. I was still writing songs all the time. I said to myself, Let’s just keep doing it until we get a door open, because we are not gonna wait for the opportunity to come and then restart working on music. Let’s be ready, so whenever we get the opportunity, we are prepared. That was my philosophy. You can try and win, or you can try and lose. But you have to try first. If you don’t try, you lose already.

Did you collaborate with anybody during that time?

No, not really, because it wasn’t easy finding musicians. I spent one year in New York when I first came over, but I met only African musicians there, and I didn’t really learn anything from them. We were not thinking about the same music, so I didn’t do anything with them. They were interested in reggae, Asian music, jazz fusion.

Then I moved to Delaware and tried to meet some musicians, but most of the people that I met were in R&B and rap music. It’s only when I came to Nashville that I really started meeting musicians and playing with them.

Did any songs from that era end up on Come Back to Me?

Yeah, I had a lot to choose from on this album. “Sweet Rainbow” and “Cherie Vico” were already written, but I gave them different arrangements. “La Petite,” same thing.

How did you keep up your guitar chops during those years of professional inactivity?

By working on guitar harmonies, and working on chords. But as far as picking and guitar technique, not much. A little bit of soloing, also, because I wasn’t playing solos at all until I got here, and I noticed that every time I had people playing a solo for me, it wasn’t right. So on all my demos, I do my solos myself, and I send it to people when we have to play, to give them an idea of what I want, where I want my music to go.

How closely does the music on the album match your demos?

On “Kavudu,” I did everything myself; the demo is on the album; “Birds Go Die Out of Sight,” just a little bit. But the thing is, I’m open to new ideas when we’re recording. I don’t tell the musicians to just copy what I did. If you bring up something better than what I played, I’ll take it.

On “Sweet Rainbow,” the guy who played the solo was really great: Pat Sansone [of Wilco]. And he did things way better than what I did.

On the Congolese music, I was just playing chords, because I was mostly singing. Actually, it’s because of the singing that I came to play guitar

Peter One

What music inspired you to play guitar?

Ivory Coast is a place where all kinds of music could come and pass by – American music, English music, French music, African – I was listening to all that, but my preference went to music with acoustic guitar and nice vocal melodies very early.

The first time I heard [Simon and Garfunkel’s] “The Boxer” on the radio, it touched me. And later on, I heard a lot of other songs and other artists from the U.S. Some of them I even thought were from England, like Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. [laughs] But some African artists were doing music that was close, like G.G. Vikey, Eboa Lottin and Francis Bebey.

There are so many African music styles around. I was listening to Congolese music just to train my fingers, and also Afrobeat, just to be able to play with friends. You bring up songs and you invite friends to play. Even if you don’t like this kind of music, when you get with a group of friends, you have to participate. So that’s also why I was learning all the Congo music.

What about playing Congolese music was helpful for you?

On the Congolese music, I was just playing chords, because I was mostly singing. Actually, it’s because of the singing that I came to play guitar, because there were some songs that I had a hard time getting the beat on time. African music is sometimes weird; the beat is difficult. So I said to myself, If I play an instrument like guitar, I’ll probably get it. That’s how I came to start learning guitar.

What guitar techniques or scales did you study?

I did not really study. [laughs] Study is a big word. I just looked at the charts and saw new chords, like the nines, the major seven, the 11, the minors… All these things. I played them to see if it sounds nice to my ears. If I can find a melody, I go ahead.

You’re a fingerstylist. Did you pick up your style somewhere or develop it on your own?

I learned it by listening to other African musicians. Then I started listening to American music, Simon and Garfunkel especially, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. As a matter of fact, one of my songs on that first album, “African Chant,” I got [the intro] from the CSNY song “Helplessly Hoping.” If you listen to them both, you’ll see it’s close.

West African audiences called you “country,” but it’s not down-the-middle country. You bring some other elements and a singer-songwriter’s approach to it.

When I started playing this kind of music, for some time I didn’t know it was called country music. Even when I met my friend, Jess Sah Bi, by that time I already knew “The Boxer.” I knew Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel; I knew about Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young; I knew about Cat Stevens. But to me it was just folk music. We were doing just folk music and African music. But people will label that country music, so we took that name just for marketing purposes.

I’m lucky to be able to get what I’ve been longing for

Peter One

Stylistically, there’s really so much to love about Come Back to Me. What is your writing process?

Sometimes a melody comes to me, and I pick up my guitar and try to put music on it. Sometimes I take the guitar and look for something – I don’t really know what I’m looking for – and melody comes. I get the song right there, and put a melody on it. Sometimes when I’m driving, a melody comes to me, so I record it on my cell phone. If it interests me, then I work further on that.

You’re a trilingual artist. Does the natural rhythm of the language in which you’re singing dictate how you play guitar?

Sometimes, but it depends on how I want to build the song. If it’s a song that is inspired from traditional music, traditional beats or things like that, the beat will be more based on the rhythm of the language. But if it’s a song that has nothing to do with the traditional style, then it’s different. Not all the songs follow the rhythm of the language.

How does it feel, after all these years, to be playing shows and making records again?

Young again, and happy. It’s just wonderful. I’m lucky to be able to get what I’ve been longing for.

Visit the Peter One website for more info.

Jim Beaugez has written about music for Rolling Stone, Smithsonian, Guitar World, Guitar Player and many other publications. He created My Life in Five Riffs, a multimedia documentary series for Guitar Player that traces contemporary artists back to their sources of inspiration, and previously spent a decade in the musical instruments industry.