“They were chasing success. I had my own vision, and after 'Strangers in the Night,' I split.” Michael Schenker brought UFO global fame. He had other plans for himself

As the guitarist releases his new album of UFO covers, he recalls the forces that led to his departure

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

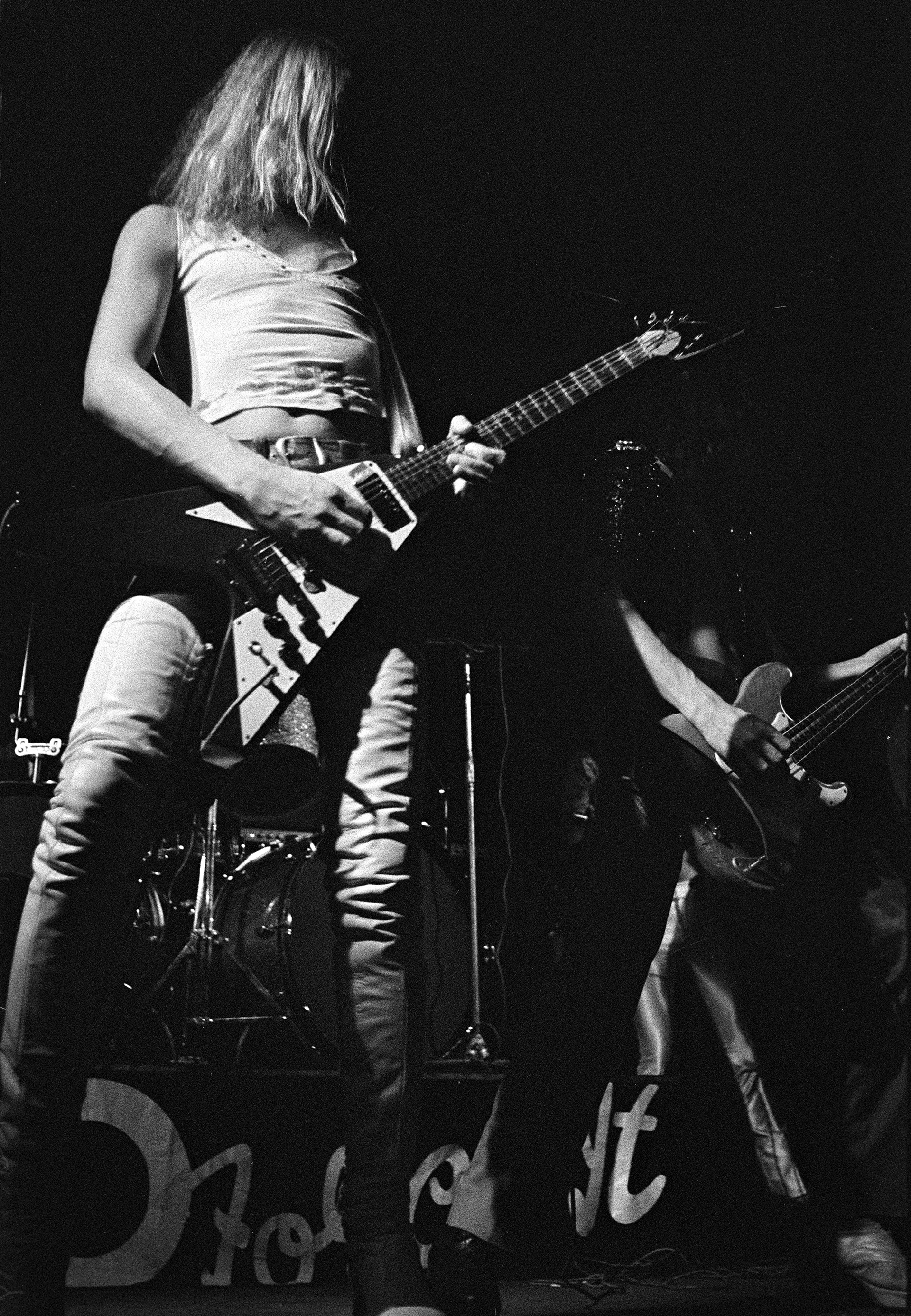

Cocksure arrogance has always been a key cog in German maestro Michael Schenker’s proverbial wheel. Whether as a straight-up kid with the Scorpions or as a nineteen-year-old wunderkind with UFO, the leather-clad, Flying V-toting six-stringer generally refuses to conform.

If you were to ask Schenker, he’d tell you that this isn’t so much by design as it is a subconscious way of life aimed at what he calls “pure self-expression.” To that end, Schenker is winning, as he’s played a role in some of rock music’s most iconic records, meaning, for the most part, he’s been able to have his cake, and eat it, too.

Fresh out of the Scorpions in ’74, and armed with a Gibson Flying V, the story goes that a young electric guitar player couldn’t have cared less about UFO — they were merely a vehicle for his dream of playing lead guitar for an English band. Really, it could have been just about any band, he’ll tell you, but UFO came calling first.

What immediately followed was 1974’s Phenomenon, an album full of sonic bombast guided by Schenker’s tail-gunning licks on cuts like “Doctor Doctor” and “Rock Bottom.” But the fun didn’t stop there, as UFO, a band that Schenker describes as a former “space rock” group rattled off heavier-than-heavy records in 1975’s Force It, 1976’s No Heavy Petting, 1977’s Lights Out, and 1978’s Obsession.

It seemed that Schenker had everything he wanted, but according to him, large-scale success was never part of the plan. “When it came down to Lights Out, which was a hit, I kind of backed off,” Schenker tells Guitar Player. “It became successful, and subconsciously, I could feel that it would become something that was no longer free.”

And for Schenker, a renegade through and through, world domination and all that came with it would never do. “It was going to be ‘You have to do this, you have to do that,’ you know?” he asks. “That freedom being taken away… I did not like that.”

After Obsession, he recalls. “I realized how much success Phil [Mogg] was after. He told me after No Heavy Petting, ‘If it doesn’t make it, I’m going to quit.’ I knew he was chasing success, fame, money, or whatever. I was not. I was the exact opposite.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Schenker was brought into the UFO fold to wave his six-stringed magic wand and take them to the next level. He did just that, and as the band was peaking, he ripped the carpet out from under them, but not before gifting them what many feel is the defining live record of the 1970s, 1979’s Strangers in the Night.

Of course, he did it his way, refusing to overdub a single track—even if there were mistakes—and hitting the road shortly thereafter. “I left because I did not want to have one direction,” he says. I didn’t want only that just because everyone else wanted it. I had my own vision, and after Strangers in the Night, I split from UFO.”

“There were a few reasons for that, but the main reason is that I knew I didn’t want what they wanted. I would have been a mismatch. We all would have been very unhappy, just like I was with the Scorpions. I would have bene very unhappy if I had to do what they were looking for. And they would not have wanted to deal with what I wanted.”

Schenker did return to UFO from 1993 to 1995, again from 1997 to 1998, and finally, from 2000 to 2003. But overall, the tumultuous nature of his membership is nearly as infamous as the music itself. In recent years, Schenker often reminds those who ask of his former UFO savior status, and so, it should come as no surprise that he’s reimagined eleven of UFO’s classic tracks on his latest release, My Years With UFO.

Another aim is to remind the world that he wrote “80 to 90 percent of UFOs music” during his ’70s tenure. In other words, Schenker felt slighted, and did something about it. “There are many generations that have been aware of this music,” he says. But without any information, I thought it would be a great idea if I gave some details from the past.”

It’s an interesting project, and its numerous guest spots from Axl Rose, Joe Lynn Turner, Slash and others will make it fun for rock and metal fans of all shapes and sizes. But for Schenker, like his years with UFO in the 1970s, it’s just another moment in time that’s sure to pass.

“Nothing ever stands still,” he sighs. “Everything is always changing. And therefore, I cannot go to a place and say, ‘Oh, I wish I could be in that place forever.’ I don’t want that. I want to be in a place of constant development and keep moving on.”

"I cannot go to a place and say, ‘Oh, I wish I could be in that place forever.’ I want to be in a place of constant development and keep moving on.”

— Michael Schenker

You’ve put a lot of distance between yourself and your work with UFO. Why revisit it now?

Well, it’s the 50th anniversary of Phenomenon, the first UFO album I did, so that’s the main reason to celebrate. But also, over the years, a lot of webmasters have come out with less and less information about everything; it’s just a name and a title, and there’s nothing else. I wanted to take this opportunity to educate newcomers.

Are you talking about a lack of songwriting credits?

Yeah, of course. You can at least mention who wrote what song, right? It’s fine; people get music for free, but it has to have information that comes with it. I think it’s important that we know more about these songs.

Can you call out specific examples of songs that aren’t appropriately credited?

No, I mean… I just picked all my songs from the 1970s for this new album. All the songs I re-recorded are my songs. And the main reason I recorded my own songs — and 80 or 90 percent of the albums are my songs — is to showcase them. Every time we made an album, like Phenomenon, all of that was decided between the band. But, of course, I wrote most of the songs throughout those albums.

And those were UFO’s most successful years.

Yes. From ’74 to ’79.

UFO made two albums before you joined, but they were very different. Is it fair to say you completely reshaped the band?

Yes. I love music. I’m an artist and love pure self-expression. What I’ve been doing for all these years is basically not listening to music, which helps. But UFO specifically was not important for me; when I was with the Scorpions, I always told them, “If an English band asks me to join, I will do it anytime, no matter who it is.”

Why did it matter that they were English?

Because that’s where the music came from that inspired me. Those people understood what it meant to express that kind of art. When UFO heard me play and asked me to join, that was it. But they were a space-rock band, so when I joined, we wiped that away.

"I came up with this very long guitar improvisation. I’ve always been very good at doing that on the spot, so 'Rock Bottom' was a big, long guitar improvisation."

— Michael Schenker

That seems like quite the task for someone who was just 19 years old.

Yes! When I arrived in ’74, I was 19. I immediately started writing music, which was the Phenomenon album, which had songs like “Doctor Doctor” and “Rock Bottom.” I completely reshaped the style of music from what UFO was doing before I joined. And so it became a hard rock band… maybe a little bit harder than “hard rock,” or whatever you want to call it.

You mentioned “Doctor Doctor” and “Rock Bottom.” How did you approach those songs from a guitar perspective?

Most of my compositions were instrumentals, and “Doctor Doctor” started as an instrumental. Phil [Mogg] heard it and said, “Oh, I love this. Can you play me the basic chords so I can put some vocals on it?”I said, “Okay,” he did some vocals, and it became “Doctor Doctor.”

“Rock Bottom” was a little bit different. I came up with this very long guitar improvisation. I’ve always been very good at doing that on the spot, so “Rock Bottom” was a big, long guitar improvisation. And then, Phil again asked me for the basic chords, he did his vocals, and that’s how it happened.

The re-imagined version of “Mother Mother” features Slash. Was finding space for the two of you on one track a challenge?

Oh, it was no problem! But the thing was, Slash was playing over me I was like, “Wait a minute, why are we doing this? We can save so much time and focus on finding the special spots. This is my spot.” So Slash filled in all the gaps where I didn’t play, and it went great.

You mentioned earlier that you didn’t listen to much music while originally writing these songs. Is the idea that your inspiration is purer?

No, I didn’t listen to music, and I don’t now. I had started doing that when I was 15 years old, and subconsciously, I was already on my way. I was already in self-expression, so I wasn’t influenced by other things; I cut them out. The brain is like a sponge, and what we hear we attempt to copy. I knew that, and my mission was self-expression. Period.

"Slash was playing over me I was like, 'Wait a minute, why are we doing this? We can save so much time and focus on finding the special spots.' "

— Michael Schenker

I get the sense that you felt you might have been a cut above as an artist. But how could you know for sure if you weren’t listening to others?

I had no clue. All I did was beat down becoming an electrician or some other profession. I was doing music, so I was happy; I didn’t need much more than that. I was never wondering, “How can I buy more furniture, a big house, or a car?” None of that was part of my vision.

Is that mindset why you’ve managed to fly just below the mainstream for a lot of your career?

I was lucky in that I never signed a deal with a big management company that would have used me to make money for them. That would have been a disaster for me; I probably wouldn’t be alive anymore. I know that.

Management just pushes and pushes regardless of whether people are feeling well or not; they drain the last pennies out of you. I didn’t want to be part of that. I’ve been fortunate that I escaped, though I almost had a pen in my hand.

Still, you succeeded with UFO, and by the end of the ’70s you’d recorded Strangers in the Night, an iconic live album. Is it true that you refused to record overdubs on the album, a common practice at the time?

Yeah, that’s true. I don’t really like doing overdubs because to my ears it always sounds like it’s fabricated. I don’t like that feeling. I like to be happy with what I’m doing. Sometimes, I kind of overlook a mistake and say, “Whatever,” and just forget about it rather than fix it. Usually, it works, and I’m also fortunate that I don’t make too many mistakes. But things happen, and you can’t always do the best thing, and you screw up. That’s part of life.

Is it also true that you felt the performances chosen for Strangers in the Night could have been better or that they chose the wrong ones altogether?

Yeah. We did two takes. One was in Chicago, and the other was in Louisville. I felt it really should be up to me to decide which guitar performances I preferred, but I guess maybe there was something wrong with the one performance, or the whole band didn’t play well. The producer usually has the last word, so I had to swallow it. And there’s a few mistakes on “Rock Bottom” that have become so famous that those mistakes are now actually part of what people like.

To your earlier point—that’s a good reason not to mess with the recordings and overdub.

Yes. In that case, the mistake has become a great thing. And, you know, that’s fine with me, too.

Mistakes and all, how do you measure the importance of your UFO years on your development as a guitarist?

My whole life is development. Every step in my life, as the clock ticks, you know, every second I’m moving forward. I keep developing into something more until I die, and I’m happy with every piece of development.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Rock Candy, Bass Player, Total Guitar, and Classic Rock History. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.