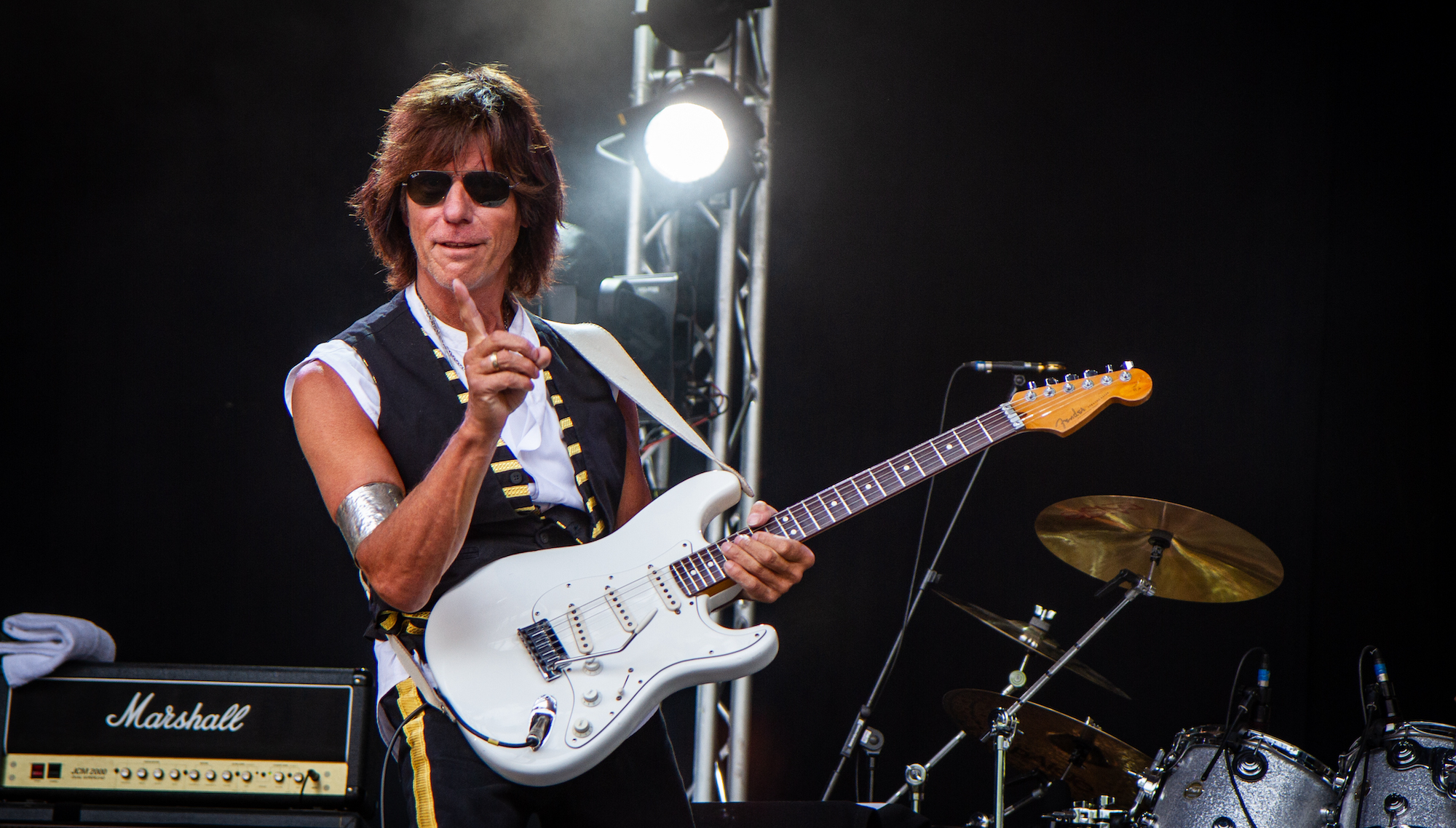

Jeff Beck: "I’ve Done a Whole Tour with a Fender Twin When Stevie Ray Vaughan Was Going Through About Four Billion Watts... He Asked Me, ‘What the Hell Are You Using? Are Your Amps Under the Stage?’”

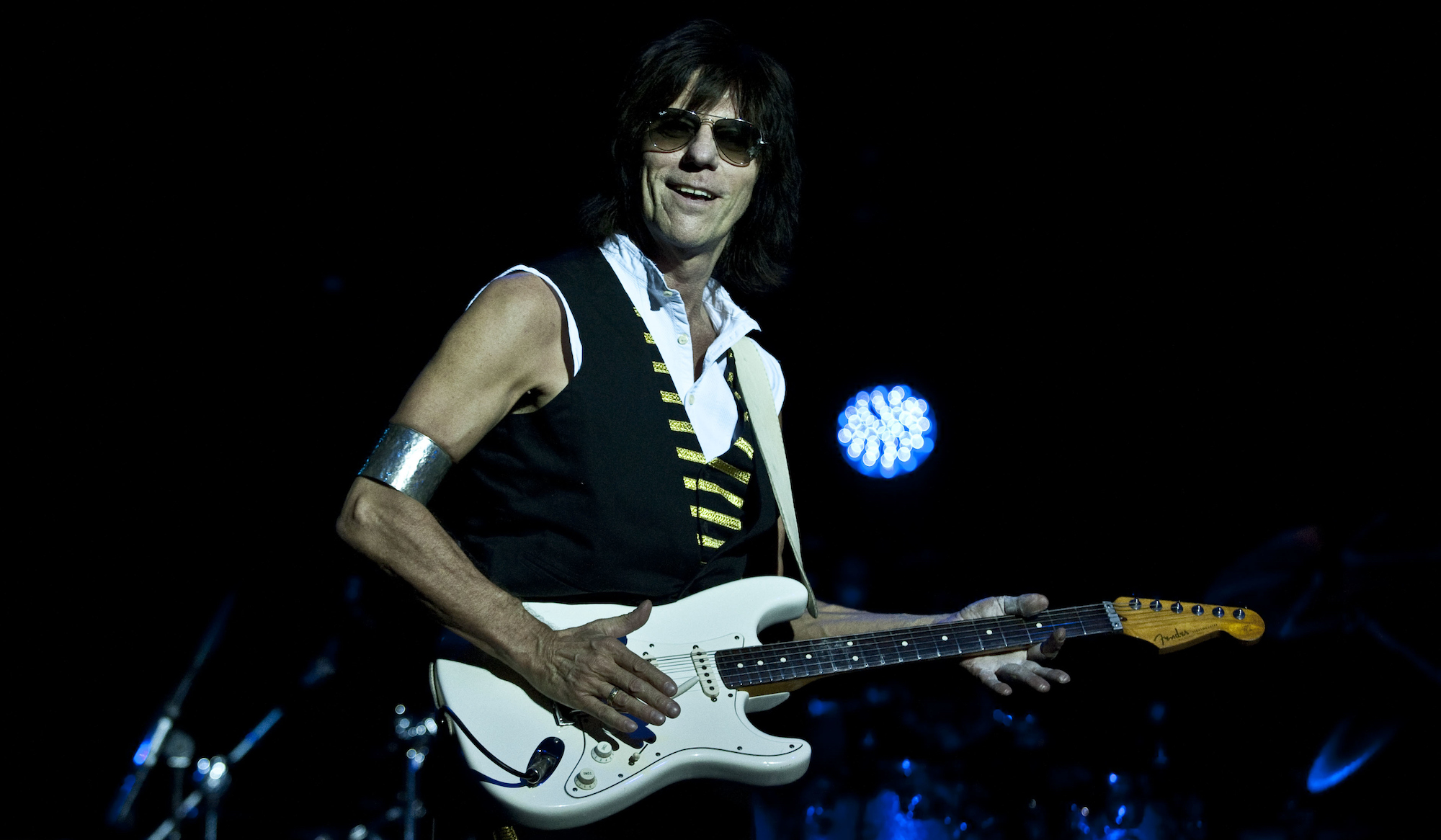

The late Strat-master discusses his thoughts on volume (and when loud becomes too loud), playing classical melodies on the electric guitar, and why he favored a trusty Fender amp onstage and in the studio.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This interview originally appeared in the June 2010 issue of Guitar Player.

There’s a nomadic spirit in Jeff Beck’s personality that causes his muse, and often his physical being, to push on to new frontiers even when the place he’s at would seem to be the perfect altar for him to preach the gospel of godly guitar.

From his Yardbirds era and onward, Beck has had the habit of changing direction or even completely disappearing just when the planets seemed perfectly aligned in his favor. But genius rarely follows a road map, and Beck’s willingness to risk short-term gain in order to make lasting musical statements says a lot about his integrity and why he’s still out there creating vital and exciting music while many of his peers from the British Invasion generation haven’t been able to top what they did in the ’60s and ’70s.

Most recently, and after a fairly long hiatus following the release of his last album (simply titled Jeff), the Guv’nor surfaced like a submarine-fired missile to wow the crowd at the 2007 Crossroads Guitar Festival. And it wasn’t just his awesome playing that created the huge buzz – a good deal of the clamor was due to Beck’s sly enlisting of a very talented bassist named Tal Wilkenfeld to play alongside veteran rock drummer Vinnie Colaiuta and keyboardist Jason Rebello.

The performances that followed – including the 25th Anniversary Concert of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame at New York’s Madison Square Garden – were heralded as Beck’s best ever. In 2009, Beck was inducted for a second time into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and he released the platinum-selling Live at Ronnie Scott's DVD, which also garnered him a Grammy nomination for his instrumental rendition of the Beatles tune “A Day in the Life.“

Of course, after all this success, what else could Jeff Beck to do for an encore other than completely rearrange the furniture by launching a new album titled Emotion & Commotion, which finds him fronting a 64-piece orchestra on several tunes, including “Over the Rainbow,“ Puccini’s aria “Nessun Dorma,“ and an instrumental redux of Jeff Buckley’s performance of “Corpus Christi.“

Beck was clearly savoring the surprise factor when he said, “I think this album will shock people when they hear it. It’s not what they expect of me.“

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

During my interview with him at the Sunset Marquis hotel in Hollywood, Beck described the new album this way: “It’s Spector-esque, if you’ll pardon the expression. It leans more towards a pop-rock sort of album than would have been the case if we’d done a classical album, which would have had to be bowtie- and put-on-me-tux proper. But it’s not like a drum and bass record that people can talk over and drink over.

“In a lot of clubs, there’s not one person listening to you, it’s just one big background noise. I wanted at least an album that could be listened to and be really plugged into. Maybe after a long day, you’ll go sit there and listen to it. It’s got just enough tweak to get you going, but it’ll lull you as well.“

Produced by Trevor Horn and Steve Lipson, and recorded last year at Sarm Studios in London, Emotion & Commotion showcases some of Beck’s most beautiful playing ever – his soaring tones and fluid vibrato making even such a mournful orchestral tune as “Elegy for Dunkirk“ (from the film Atonement) something to behold. Like a great opera singer, Beck delivers every note with such intense feeling that you may not even care that there isn’t an abundance of ripping lead work here.

Asked whether he purposely reduced the notes-to-bar ratio in order to reveal some deeper elements in his playing, Beck answered, “Absolutely. I wanted the beauty to be there without the embellishment. I didn’t want any showing off. In fact, I just found it so foreign to try to jump when it wasn’t necessary to jump.

“The songs we’re talking about didn’t require any shredding, though they’ll probably end up that way if it becomes a regular format with the orchestra. When we were making the record, I just kept saying to myself, ‘don’t get too cheeky.’“

Still, Emotion & Commotion doesn’t entirely ignore the needs of those who simply crave a dose of Beck’s fiery guitar playing, which comes to the fore on the songs “Hammerhead,“ “There’s No Other Me“ (featuring the Colaiuta/Wilkenfeld rhythm section), and “I Put a Spell on You“ (sung by Joss Stone), where Beck knocks off a killer blues solo backed by Clive Deamer on drums and Pino Palladino on bass.

At the end of the day, Emotion & Commotion stands as an honest and completely uncontrived statement from one of the most singularly unique guitarists on the planet. It speaks to the inner workings of someone who, despite having some serious misgivings about the process of making records (more on this later), obviously loves creating the aural equivalent of fine art and is unencumbered by the need to satisfy anyone but himself and his loyal fans.

So as surprising as Emotion & Commotion is on a certain level, it hardly seems all that unusual for Beck, who has a history of turning loose elements into sonic marvels. As he himself put it: “Making this album gave me a similar feeling with somebody else doing the orchestration and making stuff happen the way George Martin did on Blow by Blow. When we started that album we had very little material as well. After the event, I started to realize how close it was.“

What are the benefits and downsides of going into the studio without having the music fully prepared?

“The benefit is that you are thrust in. In some ways it’s better to not be too prepared. The biggest pitfall there is that you are going to sound over-rehearsed and too contrived. It’s a weird process to try and remember the chain of events that led up to how we did this, but my manager is very forceful, and he has a way of persuading me to go in unprepared. 'Oh, it’ll be great,' he goes. And the first two weeks was miserable. Not that the other players weren’t good, but they were unsuited to the sort of thing I was looking for.

“It wasn’t until I came away that I realized I’d lost two really good players who just weren’t on the same wavelength with me. But you live and learn. It was folly to go in with a bassist and drummer that I’d never heard of. It was weird for me that Tal and Vinnie weren’t there – we should have gone in with a band situation. Of course, there was the stuff with just me and the orchestra, which didn’t require any bass or drums at all.“

I can’t stand listening to people do covers of great songs who think they can write better than the original composer. If the melody was worth having in the first place, then leave it alone

Why didn’t you want to use the bassist and drummer you’d been playing with for the last two years?

“Well, to get them over to England for three or four tracks just didn’t make sense. So we ended up doing it without them. But then we had to fly Tal over to do the bass part. And to repair some of the drum parts that were not that great, we actually sent the producer over to the States to record Vinnie. So it kind of ended up costing more in the long run, but at least they’re on the album, and they did a great job on the tracks.“

How does the high expectation that people have of you affect your creativity?

“I’m more than overwhelmed by it, but that pressure is not the most desirable feeling. Even though it’s all very complimentary, I go in the studio with this feeling that I’ve got to not let these people down. And then, down comes the big concrete boom on the head. And if it’s a bad day or a non-productive day, I start thinking, 'I can’t do this.'

“The secret, of course, is not to worry about it and just go in and make the nicest sounds you can make. And if those sounds move people, then let it go. But I don’t want to think about how to impress the world. I’ve done enough of that, and I think reaching people is the magic thing now.“

What have you been listening to for inspiration?

“Lately, I’ve just been listening to opera singers and other great singers. Not so much blues, because they’re all about embellishment, and it’s all in the throat – but someone like Pavarotti, who has just the most passionate and full sounding voice. In fact, we were going to put Puccini’s 'O Mio Babbino Caro' [from the opera Gianni Schicchi] on the album – it’s just a fantastic song. But that’s too classical, and I wanted to save it for a classic album that will hopefully be done with the London Philharmonic.“

What was the reason for doing an album now that features orchestral pieces but isn’t full-blown classical?

“I had always wanted to see what it would sound like playing with a really classy string section. I’d previously made an attempt at doing a classical album. I wrote a list of about twelve tracks from composers that I loved – from Puccini to Ravel to Mahler – and they were beautiful songs that lent themselves to single-note melody. And then I did Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 with the New York Philharmonic. The result was quite stunning really, so I took it along to EMI Classics and they fell in love with it.

“They asked, 'Where’s the rest of it?' And I told them, 'This is it – this is the bait we’re throwing out.' So they said they’d be interested if I could do 11 more tracks like that. They gave me half a dozen fabulous CDs to listen to, and that’s as far as it ever went. But I did love the sound and the emotion of surrounding my guitar with all that instrumentation.“

How do you interpret a classical piece in order to make it more guitar-centric?

“I learn the melody completely off path and I play it like a blues, or as bluesy as I can. I use artistic license up to a point, but I can’t stand listening to people do covers of great songs who think they can write better than the original composer.

“If the melody was worth having in the first place, then leave it alone. If you play it with all the feeling but without any embellishments, then sometimes you can slip around a little bit. But with a great piece you just don’t. If the melody was crafted well enough to go with the chords, then the job’s done.“

What’s the biggest challenge of arranging a song to play with an orchestra?

“First of all, can I pull it off live? You need to make sure the song can be played live, otherwise you’re going to get yourself into big ditch and never get out of it – especially if you’ve got Olympic leaps all over the place and stuff like that. It’s got to be played in the way the blues would be played. It has to feel that natural.“

Your tones on this album are beautiful. What amps did you use?

“I’ve found that my best friend is the straight-ahead amplifier with very little effect pedal. If distortion is needed, I’ll use a much smaller amplifier and overload that rather than use a pedal to alter the circuitry. When you go through a pedal you’re going through some guy’s circuit before it gets to the amp. I want the amplifier to get the most honest and direct signal from the pickup. That way, you get the tonal advantage of the guitar and the fingers.

“I’ve adhered to that, and I think you can hear it on the album without any B.S., except for a couple places where I used a ring modulator – like for two bars on the Joss Stone track 'There’s No Other Me.' You know, Jimi Hendrix didn’t use too much of that either. He used one effects pedal and a Crybaby wah-wah, and he just cranked the hell out of his amplifiers.“

Why did you switch to Marshall plexi reissues, which have less gain than the JCM2000s you had been using?

“I was looking for purity of tone so it wouldn’t jar with the orchestra. I couldn’t hear a shred tone like Steve Vai gets, or even Brian May or Billy Gibbons, who have these very fat, distorted guitar tones. I just couldn’t really see that working, so I tried to get the sound of my guitar as natural and organic as it could be. Like on 'Over the Rainbow' or 'Elegy for Dunkirk,' those are just right honest performances with just me and the orchestra.“

You still get a lot of sustain on those tracks, so is that the Marshall turned way up?

“No, it was a Fender Champ. I joked once about making an entire album with a Champ, and I just about did that this time. In a couple of places there’s a 50-watt Marshall with a 4x12 speaker cabinet, and I think that’s on 'Lilac Wine' and 'Corpus Christi.' Those songs were done in the studio live with a mic placed several feet away. But when we got into the overdubs I just ended up with a Champ. Mine is a 1950s model with that brown rag across the front – the tweed, you know? It sounds amazing really, and you don’t need volume.

“Some people can’t do without lots of volume to get their tone, but I think if you can’t get it without four million watts, something’s wrong. Because a mic doesn’t read volume, it reads tone. You’ve got all the level in the world at your disposal in the console, and the remixing and the rest of it to compensate for lack of power. But the tone is the thing, and that’s something that came from Scotty Moore, who once told me, 'Get some better tone and you’re there – volume you don’t need.'“

Can the small-amp/less-volume concept work for live playing?

“By using the P.A. to act in the way it was designed – which is play at low level and use all the distortion and whatever else you need, but make sure you don’t come out louder than the side-fill monitors or the front wedges – you can blow the house down, and I’ve done it.

“I’ve done a whole tour with a Fender Twin when Stevie Ray Vaughan was going through about four billion watts with a rig that looked like an amp shop. He asked me, 'What the hell are you using? Are your amps under the stage?' I said, 'Nope, that’s it right there.’ [Laughs.] But we spent quite a lot of time dialing in the sound and getting rid of the squeaks and squeals. We’d raise the level and then tweak it a little bit, and then we’d raise it a little more. You can’t believe what you can get out of a little tenor 20-watt amp.

“I think Billy Gibbons is on that route as well, as he plays though some blown-up little thing now. You have to work in symphony with the amp for what sounds best, and it depends on what you’re playing. If it’s power chords, then you’d probably use a slightly bigger amp, otherwise it’ll shred down into a narrow bandwidth. Most of the time, though, you can get away with a couple of Champs – one clean, one distorted – and use the clean one to get more definition.“

What has led you to being more concerned about volume?

“The louder the stuff is on stage, probably the worse it’s going to end up sounding. Your hearing goes, your pitch goes, and you can’t really hear any depth of field. If you have to question whether it’s too loud, then it is too loud. The power has to be there, but without the level. But if you’re going to be loud, get the speakers away from you. Lately, I’ve been one putting one 4x12 facing backwards, just so that the P.A. guy doesn’t go around the bend with too much volume.

“I’ve also seen Pete Townshend with a stack of Fenders facing each other like a sandwich, so the audience only gets the back of it. Sounded great to me, but I haven’t gone that far. On a big stage, I might put four Marshalls up there, like two big stacks, and have them right at the back just to see what they sound like wide open. But they’d have to be damn deep in the stage so there’s not too much spillover. I’ll try that on this tour, but I’ve got a feeling that the little Champ will win out because the orchestra and the Champ are going to sound in proportion.

“I played with this powerful band that had 18 pieces, and I thought I’d need a Marshall for it, but I didn’t; I needed a Pignose. Even though the trumpets and the horns were blasting away, the difference in character of the guitar with that concentrated trebly sound just cut right through.“

Did you use anything other than a Strat on this album?

“I went through about five different guitars, and they all got put back on the rack. We did one song with a Gretsch and some with Guild even, but they just didn’t sound like me. I picked the Strat back up and, boom, there I am again. So why go against it?“

Since you play with your fingers, do you use heavier gauge strings?

“My guitar is strung pretty lightly now because I haven’t played live for a while. But, by mid-tour, I’ll go to a .012 on the first and a .052 on the bass. It’s self-torture, but you’ve got have that. The great Jimi Hendrix picked up my guitar once and he said, 'What are these rubber bands doing here? You’ll never get tone out of that.' I was really disappointed because I thought I had found what I was comfortable with. But he was right, there was no guts in there. And there was no effort.

“The half of playing blues is you have to suffer the pain of the wire digging into your fingers. And the more you play, the harder your fingers get and the fatter your strings can get.“

What were you playing when Hendrix said that to you?

“A Les Paul, which is kind of a sissy guitar compared to a Strat anyway. The Les Paul is heavier, but because of that bulk you can do bends on it more easily. Also, the Les Paul’s lack of a vibrato arm means you’re not wrestling against the spring-loaded bridge all the time.

“The Strat is the ultimate because it’s like having a miniature pedal steel within it. Once you get familiar with where the bends are and where they meld down into a fourth or whatever, you can do all kinds of pedal-steel-like things, which I think are cool. Some of the things that sound the most difficult are the easiest for me.“

Despite having your Strat set up with a floating vibrato, you don’t ever seem to touch the tuners, let alone switch guitars during a show. How do you stay in tune?

“Sometimes it’ll goes out if it’s a wild gig like Crossroads where there’s like 40,000 people and I go shredding all over the stage. But unless those situations happen, the guitar stays pretty much in tune. The strings are pre-stretched to start, and they’re stretched to almost the breaking point before I go on. Then they’re retuned and retuned.

“So far, I’ve been lucky. I’ve broken a few, but it’s more likely a flaw in the string somewhere around the bridge area that causes it to break rather than me playing it. But I do drive them pretty hard.

“Also, the roller nut that I designed seems to work pretty well – especially for the top three strings, which stay in tune really well. It has a double roller system, so the strings go over two rollers, and for some reason they don’t hitch up. Because you get a lot of lateral movement when you depress the tremolo arm – the string actually moves across the nut – and sometimes it doesn’t come all the way back, and then you’re in trouble.“

The way you use the vibrato on “Over the Rainbow” it sounds like you were actually trying to mimic the warble in Judy Garland’s voice.

“That’s what I tried to do. It started out as a bit of tongue-in-cheek thing, but when I got halfway through, the whole place was soaked in tears. Vinnie is a tough guy, but even he was going, 'Jeff, stop. I can’t bear it!'“

The melody you came up with for “Elegy for Dunkirk” is even more of a tearjerker.

“That’s probably the deepest thing I’ve ever done. I picked that melody out from the original score. I haven’t seen the film Atonement, but I’m pretty sure I know what I’m going to see, as it’s the end of the Dunkirk landing.

“When I heard it, I thought first of all that it was an ensemble piece for the violins and cellos. But I picked out the melody and made it a really nice piece. I altered it by putting my guitar voices in a different spot, though. I played it up an octave to get away from the down-in-the-dumps kind of thing. It’s still a bit dirgy, though – a pretty sad thing.“

In the early days, the rockabilly acts used to learn the stuff and go in and count it off – 'one, two, three.' That’s what I like. I’ll never get that out of my blood

Were there any concerns about putting “Corpus Christi” as the first song on the album?

“Because you’re expecting shred and it doesn’t happen? That one and 'Lilac Wine' sort of set the mood for the album. When I heard Jeff Buckley’s versions of those songs, I was touched because they’re so gorgeous. 'Corpus Christi' is a traditional tune from the sixteenth century, and my dear friend and wife said to me, 'That melody is the most beautiful thing I’ve ever heard. Please do it.'“

Did you originally intend “Hammerhead” to be a tribute to Jan Hammer?

“That’s an interesting story. About a year ago I was sitting around a campfire with Dave Gilmour and I said to him, 'If we do the Royal Albert Hall, why don’t you come and play?' Well, he kept me to it, and so at the gig I suggested we do the song 'Jerusalem,' which is very English-sounding. He said, 'Why don’t we do ‘Hi Ho Silver Lining’? – it’ll bring the house down.' I told him, 'Not on your life.' So he goes, 'What if I sang it?' So I said to Jason [Rebello], 'Look, we’re going to do ‘Silver Lining,’ but I don’t want to do that stomping, ching-ching-ching rhythm thing.' So he said, 'Right, leave it to me.'

“He knows how much I love Jan Hammer – and Jason’s a huge fan too – so he came up with a very Hammer-esque sort of riff for it. And that’s the riff we played at the Royal Albert Hall concert, which made it sound much more modern. We salvaged the riff from that song and then Jason rewrote the melody to get away from 'Hi Ho Silver Lining.' The whole song was very inspired by Jan, and that’s why I called it 'Hammerhead.'“

What kind of wah did you use on the intro to that song?

“It’s the Snarling Dogs Super Bawl, which is not really an annoying wah-wah. It just opens an envelope in a very subtle way, and the sweep is not going to take your head off in full treble like a Crybaby will. I use the wah to take the top off the guitar – most of the top anyway – so you’ve got a voice appearing. You see, I’m trying to be a singer.“

On “Never Alone,” are those actual voices that you hear in the backing tracks?

“I wanted to do some close harmonies on that song. One of my favorite close-harmony groups is the Mystery Voices of Bulgaria, who I’ve loved for like 15 or 20 years. Their harmonies are just above all reach of understanding. So I said to Jason, 'Why don’t you throw some really good voice samples on a pad and let’s listen to how I sound with voices only.' And it was much more interesting than a cheesy string pad or a Fender Rhodes pad.

“Soon as you get into these individual voices played with these complex chord shapes, your head starts going places, and that’s the result. The riff is powerful and you’ve got 30 strings playing the riff along with these amazing big chords. The voices just ring better than any other instrument, but, because of their lightness, you can put the levels up and they don’t rob too many frequencies.“

Pro Tools draws you to a place that you don’t want to be and it makes you stay there because it actually gives you something that you shouldn’t have, which is a sort of flattery – the fact that you were sounding like crap a minute ago and now you don’t. I don’t like that

Was it your idea to run the ’50s standard “Lilac Wine” and the operatic aria “Nessun Dorma” together almost as a single piece?

“No, Steve Lipson did that. I can’t praise him enough. I mean he put up with me for three and a half months, and I think he wondered what the hell he had gotten involved with after a couple of weeks because I tend to loathe everything.“

Why do you think that is?

“I hate making that commitment and then going home and not feeling like I’d actually done anything. And the money clock’s going by and it’s like, 'Oh god.' This is all a load of crap anyway because everything is phony, the whole thing – you’ve got another chance at the solo. In the early days, the rockabilly acts used to learn the stuff and go in and count it off – 'one, two, three.' That’s what I like. I’ll never get that out of my blood.“

But you could make records that way if you wanted to, right?

“It’s a question of being forced or cajoled into it by the fact that recording techniques now are different. Everything is safe and you’ve got choices. They can pitch correct your voice and put your instrument through virtual this, that, and the other plug-ins. And it’s all there. What amp do you want? All right, bonk, and up it comes, and it’s a bitch of an old Marshall. There’s too much assistance and not enough hard-edged, 'C’mon, what have you got?'

“There’s a microphone, you’ve got the amplifier, there’s the take, go and play. And that’s what I really like, and I miss that. That way you’re on your toes right away and you know that you’re going to succeed or fail. And if you don’t succeed you go back and try again.

“What I’m describing is that Pro Tools draws you to a place that you don’t want to be and it makes you stay there because it actually gives you something that you shouldn’t have, which is a sort of flattery – the fact that you were sounding like crap a minute ago and now you don’t. So I don’t like that. And I tried to make this album sound like we could play it, and I’m damn sure we can play it. It’s always in the back of my mind: 'How are we going to do this?'“

I understand that “There’s No Other Me” had to be altered in the studio because you knew you couldn’t pull it off live?

“Yes. Jason wrote the two parts for that song and he wanted me to play the long sustaining notes that make the basis of the melody, and, in-between those lines, I was supposed to shred. The problem was that we couldn’t really perform it because of the overlap – I’d have to stop playing the long notes in order to play a solo.

“So, Joss Stone was around and she’s fantastic, so I said, 'Look, just come in, you can’t lose – we’ve got a track that’s smoking, and it’s wide open for you.' So she sat there and about an hour later she’d written these lyrics. And what a performance!

“I was sitting down watching her because I didn’t want to get in the way, and she had a backless dress on. And I’m telling you, that was the most erotic, beautiful sight I’ve ever seen. The muscles she was using, and everything about her breathing – it was just an amazing sight. I wish I had filmed it. I can’t wait to play it now, which means we’re going to have to carry her on the road.“

Art Thompson is Senior Editor of Guitar Player magazine. He has authored stories with numerous guitar greats including B.B. King, Prince and Scotty Moore and interviewed gear innovators such as Paul Reed Smith, Randall Smith and Gary Kramer. He also wrote the first book on vintage effects pedals, Stompbox. Art's busy performance schedule with three stylistically diverse groups provides ample opportunity to test-drive new guitars, amps and effects, many of which are featured in the pages of GP.