All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

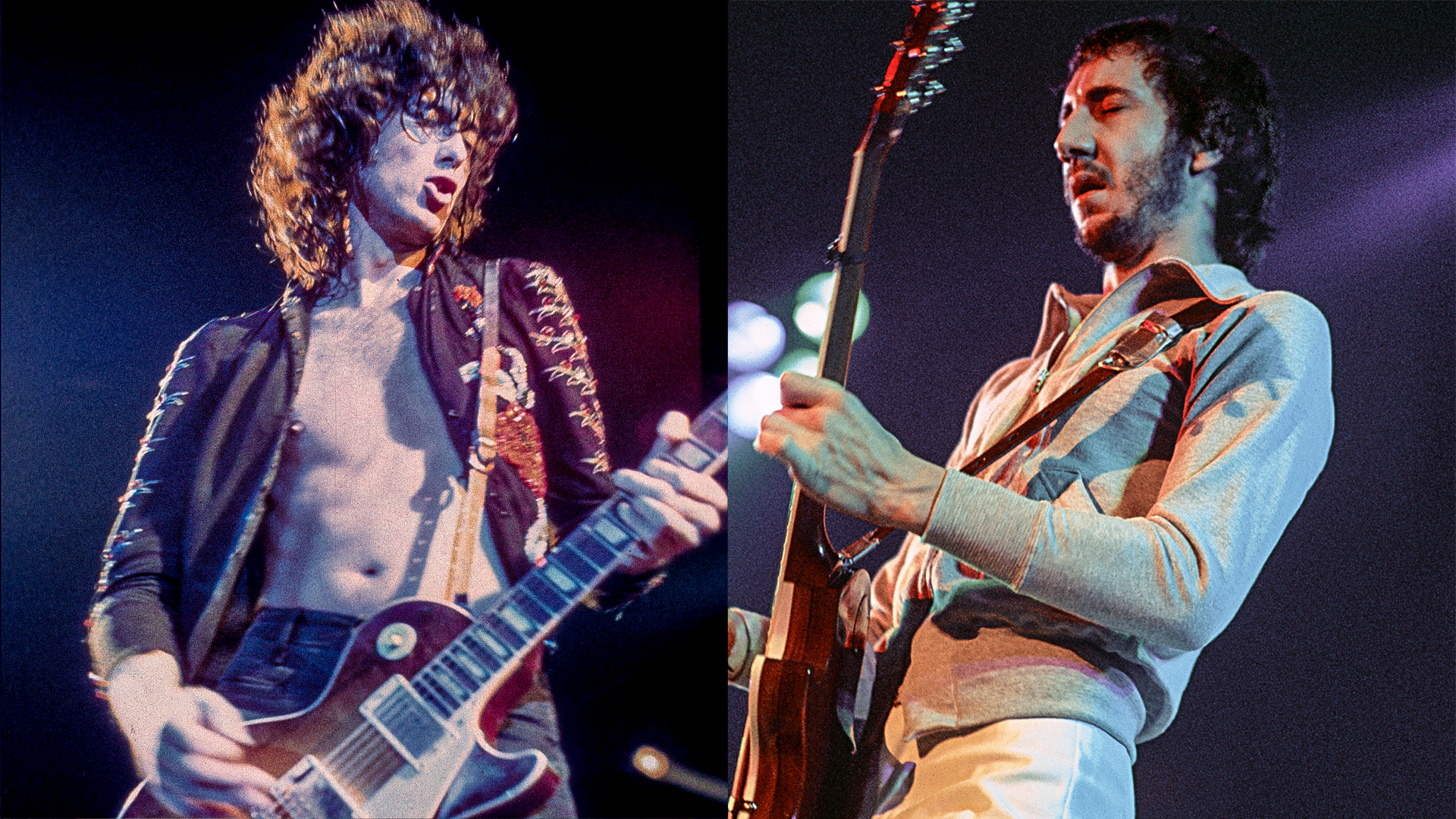

Every aspect of Vernon Reid and his music defies easy categorization.

He's a rock ‘n’ roller who came of age musically as a member of a free-form jazz group. He's a high-wattage screamer whose secret ambition was to master fingerstyle ragtime guitar.

Soloing, he can move convincingly from pentatonic riffing to post-Ornette Coleman chromatacism and back again in just a measure or two.

In this archive gem, Reid talks about Coleman’s fascinating harmolodic concept and discusses the lineage of blues, providing some interesting food for thought along the way.

We hope you enjoy this interview extract from the October 1988 issue of Guitar Player…

Your playing over the years has a lot of continuity. Even though Living Colour sounds very different from the Decoding Society, you don't seem to have compromised your approach in an attempt to "go rock."

It's funny – rock was the music I felt I had the clearest voice in. I was always struggling with jazz, even though I loved it. I loved Dolphy, Coltrane, and Ornette so much that I tried to integrate the two things.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The Decoding Society was a school for solidifying what I really wanted to do; it was my chance to integrate the blues with the harmolodic concept, to pick and choose and make it really coherent.

The Decoding Society was a school for solidifying what I really wanted to do; it was my chance to integrate the blues with the harmolodic concept

Vernon Reid

Could you explain the harmolodic concept?

The harmolodic approach was developed by Ornette Coleman. It's a theory of music that frees melody from its subservience to harmony.

Traditionally, certain chords dictate certain melodic lines, but in Ornette's theory, melody, harmony, and rhythm are free from each other; they can interact on different levels. You can play things in different keys and make it work because the combination of keys creates another, freer tonal center.

Everyone has had the experience of being somewhere, listening to music, and then hearing a radio outside playing different music. For a brief moment, you hear the two songs together and you perceive the consonances between them.

Harmolodic theory tries to synthesize that moment.

There's a great statement that you made to the Village Voice: "I don't separate Dolphy from Sly from Monk from 'Trane because the common thing that links all these people together is the blues. The blues is what links Ornette to the Temptations or Hendrix or 'Trane."

It's true. The blues is really more than a structure; it's a feeling. Once, I heard John Gilmore play a solo with [jazz composer and band leader] Sun Ra, and he played just total sound. There was nothing linear, but the feeling of the blues came across so strongly.

Or I think of the first time I heard Dionne Warwick – such a clear, clean, but still human voice. It's interesting that Carlos Santana also credits her as an influence, since he was the first rock and roll guitarist who really grabbed me.

People either try to find resonances in their lives, or they try to obscure what their life is and take on another persona

Vernon Reid

Blues is a thread that links all these different experiences. It's a matter of expressing the blues in one's life. Even getting past the point of, say, listening to Muddy Waters or Lonnie Johnson all the time, because when you do, you're listening to their lives.

The only things you can draw from them are things that resonate in your own life. Other than that, everything else will fall away, unless you're a total chameleon and you're trying to submerge your life.

People either try to find resonances in their lives, or they try to obscure what their life is and take on another persona.

It's like that Steely Dan song that says, "Any world that I'm welcome to is better than the one I come from." Some people will take on the persona of another player and say, "I want to be that, because I don't like my life."

Is the music an expression of your state of being, or is it something you're just taking on?

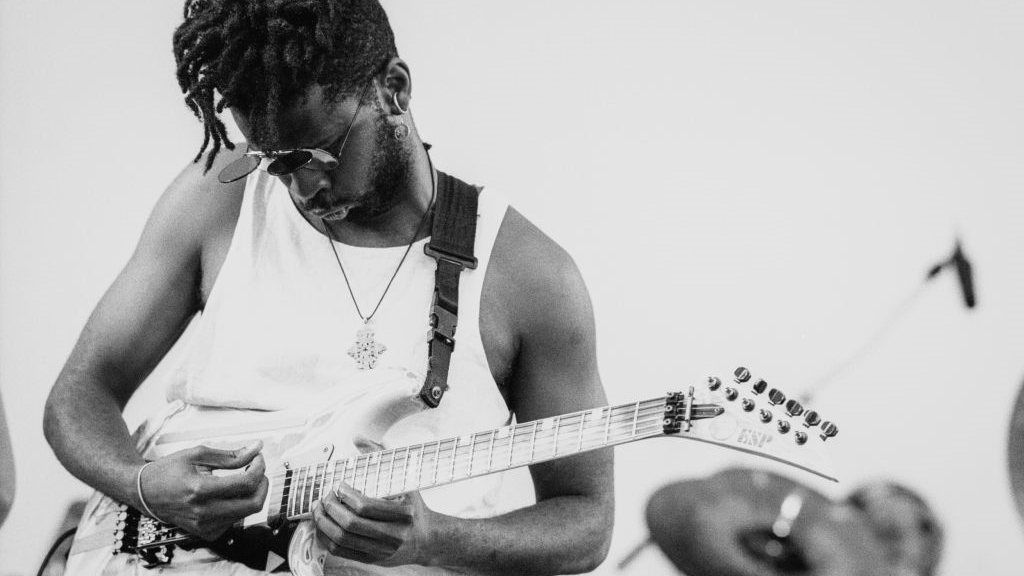

So do you consider yourself a blues player?

Yeah, I do. The blues is at the bottom of my playing. It's something that I constantly try to work with. I try to get to my center, to what I'm really feeling.

Some people will take on the persona of another player and say, 'I want to be that, because I don't like my life'

Vernon Reid

Guitar playing is a sort of feeling analysis that tries to strip away all the crap.

Sometimes you play from a predominantly pentatonic vocabulary, and at other times you use more open, chromatic sounds. Do you shift gears conceptually when you move from a pentatonic idiom to a chromatic one?

Part of it is a matter of separating myself from the tonal center. Partly, it's trying to connect with the rhythm. Sometimes I concentrate purely on what's happening with the drums and free it up that way.

I also find myself working with dominant figures along with the pentatonic and chromatic things. I do find myself shifting gears, but I'm not sure whether it's a conscious thing.

When I'm practicing, I try to think of that stuff, but when I'm performing, I try to just be in the moment.

Joe Gore is a guitarist and writer and a former editor for Guitar Player magazine. He has played on albums by Tom Waits, PJ Harvey, Les Claypool, Mark Eitzel, Tracey Chapman, Courtney Love, Eels and more. His book, The Subversive Guitarist is out now and has been acclaimed by Vernon Reid, Gretchen Menn and Dweezil Zappa, among others. For more information, visit his website.