How Santana Took Their Blues-Rock Jazz Fusion to Exotic New Realms with 'Abraxas'

Over 50 years later, Carlos Santana sits down with GP to reflect on one of his most enduring, influential works.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

”To me, there are two kinds of guitar players,” Carlos Santana says. “Some people go up and down, or left and right, and some people go deeper in a different way by bending the strings.

"Because once you bend the strings, you’re messing with microtones. And microtones are the ones that give people chills. It brings tears to their eyes. There’s something about the sound of a microtone that reminds molecules to scream.

“Once you bend the note a certain way, like Otis Rush, Ali Farka Touré, or B.B., Albert, or Freddie King, you get attention in a different way, because you start to sound more like a woman’s voice. So for me, playing guitar is beautiful in many ways, like a Segovia way or Paco de Lucía way.

“But when you stop and bend the notes – even when it’s just nylon strings – if you bend them a little bit, people go, ‘Oooooh.’ It gets sacred and sexy really quick.” Sacred and sexy is one way to describe the cover of Abraxas, the Santana group’s second album, released more than 50 years ago in 1970.

Its title refers to a deity associated with early Christians’ mystic practices, though the meaning of the word has been lost. It may be a reference to “the salvation of the cross.” And indeed, the painting on the album’s front presents a surreal and sensual interpretation of a sacred moment.

Titled Annunciation, and painted by German-French painter Mati Klarwein, it depicts the angel Gabriel as a winged, bright-red female form straddling a conga drum in a landscape filled with fruits, flowers, and other fertility symbols, pointing to the heavens as it reveals to a Black, naked Virgin Mary that she will conceive the son of God.

Meanwhile, the back cover carries a quotation from German author Herman Hesse, who called Abraxas “the god who was both god and devil.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“We stood before it and began to freeze inside from the exertion,” it reads. “We questioned the painting, berated it, made love to it, prayed to it: We called it mother, called it whore and slut, called it our beloved, called it Abraxas...”

But sacred and sexy are also apt descriptions of the music on Abraxas, in which Santana took their blues-rock jazz fusion to exotic new realms that celebrate the spiritual and carnal. Among the tracks is the band’s hit Latin-rock cover of the Peter Green–penned Fleetwood Mac song “Black Magic Woman” and a hard-driving rendition of Tito Puente’s party favorite “Oye Como Va.”

Both songs would become hits, pushing the album to the top of the charts and securing Santana’s place in rock history following their breakout success at Woodstock. The band had played an electrifying set at the festival on August 16, 1969, giving them a massive career boost just two weeks before the release of their self-titled full-length debut.

The album’s second single, “Evil Ways,” became a Top 10 hit in the U.S. But as the demand for a follow-up rose, there was just one problem: After performing the same songs for the last three years, Santana was out of material.

The band went off to write and hunt for songs, and each member came back with very different contributions. Gregg Rolie, Santana’s keyboardist and lead singer, brought his own vocal-driven rock tunes, as well as “Black Magic Woman.”

Percussionist José “Chepito” Areas contributed two Afro-Caribbean pieces that showcased his timbale chops, while percussionist Michael Carabello created a meditative mood setter with elusive wind chimes, cymbal swells, and majestic piano chords. Carlos Santana took his wah pedal and set it to a half-open position to make his Gibson cry through the wistful instrumental “Samba Pa Ti.”

As much of a classic as that ballad is today, his bandmates were not convinced it belonged on the album.

He also teamed up with pianist Alberto Gianquito to co-write an epic jazz-rock ride through briskly shifting time and key signatures, and suggested that the band should cover Puente’s “Oye Como Va.” Bassist Dave Brown would serve as the album’s engineer together with John Fiore, while Michael Shrieve once again played drums.

Sessions for Abraxas took place at Wally Heider and Pacific Recording Studios in the Bay Area in April 1970, with Santana and Fred Catero co-producing.

I think we were the only ones besides Motown and George Benson who had congas, electric guitars, and Hammond organ. But we brought a lot more street dirt

Catero was a New York producer and engineer who’d relocated to San Francisco to work for Columbia, where he recorded albums with Sly & the Family Stone (Life), Big Brother & the Holding Company (Cheap Thrills), and Cuban percussionist and bandleader Mongo Santamaría (Stone Soul).

“We knew that Fred had recorded with Mongo Santamaría, so he knew how to record congas,” Santana says. “I think we were the only ones besides Motown and George Benson who had congas, electric guitars, and Hammond organ. But we brought a lot more street dirt.”

After a month in the studio, the band released Abraxas on September 23, 1970 to a mixed critical reception. Today, it’s widely regarded as their most essential album and a rock and roll masterpiece.

Carlos Santana took time to speak with Guitar Player about the song selection and recording process of Abraxas, the role of his guitar and the gear he used for different songs, and how he sees his band’s creation 50 years later.

After Woodstock, the band was in need of new songs. How did you pick the selection of tunes that appeared on Abraxas? Was there any debate among the band members about which ones should be included on the album?

From what I remember, some things were very easy, because we trusted one another. Other things were a little challenging, because some people had a different idea of what was rock and roll and what was not. I had to put my foot down for “Oye Como Va” because I thought it was like “Louie Louie” – a forever Friday and Saturday party song.

There are certain songs, like “Who Let the Dogs Out,” “Macarena,” or “La Bamba,” that go viral really quickly. I had a feeling that “Oye Como Va” was that kind of party song that makes people drop their sorrows or problems. The other song where I had to put my foot down was “Samba Pa Ti.” I said, “It’s going on the album! Otherwise you’ll have to get another guitar player!”

Sometimes you have to fight for space on an album. It’s a healthy thing, because you’re letting people know. Plus we were all learning how to create within the compound of a band. We had developed our sound for three to four years before that album came out, because we were touring a lot. And for the first three or four albums, we did things as a band, and then, eventually, it became my band.

What was the mix of personalities like in that version of the band?

You know, we were like San Francisco street mutts. [Concert promoter] Bill Graham was the one who told us that we were something that we had no idea we were. He thought we were really different from all the other bands in San Francisco.

The beauty of that [version of] Santana was, although I never went to college, it was a bit like a dormitory: In this room you have a person who’s totally into the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, in here you have someone into Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix, and then you have another person who’s totally into Coltrane and Miles.

And with every room that I go into, I’m learning something. I’m into Gábor Szabó, Baba Olatunji, and also Coltrane. Abraxas is an amalgamation of all those who we love. It’s just that when we played it, it sounded like us.

Fred Catero was very sweet and giving, to allow the musicians to accept and get past one another to create the music

Who suggested the title?

Michael Carabello was very instrumental in how the album looked and sounded. I believe he suggested the name, and he also brought the album cover. Michael and I are still very close.

But I’m also really grateful to Michael Shrieve, Gregg Rolie, Chepito, and Dave Brown. Everybody – even the people like Alberto Gianquinto, the piano player who used to play with James Cotton, and [then–road manager] Ron Estrada and [personal manager] Stan Marcum, who found me playing in the streets, while I was still in Mission High School.

Abraxas is such an eclectic album. You’ve got psychedelic rock tunes with heavy riffs and Hammond organ, an upbeat Latin party hit, songs that sound like spiritual incantations with Afro-Caribbean percussion and group vocals, and a jazz-fusion instrumental where you’re all really stretching out. Did Fred Catero get what you were going for, or did you have to lead him?

He was very sweet and giving, to allow the musicians to accept and get past one another to create the music. Just like Teo Macero with Miles [producing Bitches Brew], he had to wait for the songs to enter and the musicians to get out of the way. But we were learning together.

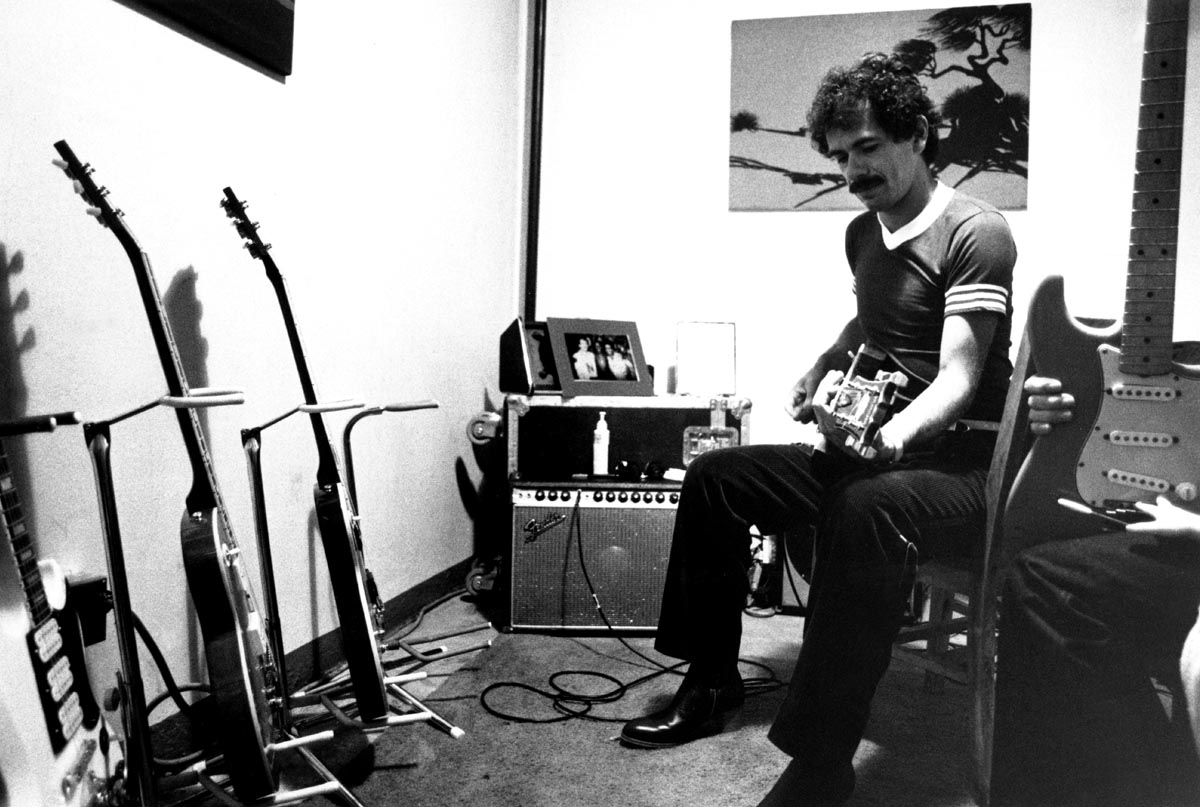

What was your process for tracking guitars?

We used three microphones for every instrument in order to also capture the room, because that’s what the ears hear. We never put microphones totally in front of the speakers.

One was far in front of them, and one was way away in a corner by the ceiling. And I’d work with every microphone, spending five minutes with each one to open them up like an aperture on a camera, because you’re letting information come in.

Otherwise it’ll sound very thin and annoying, like you’re playing through the mixing board or a pedal. I don’t use pedals, other than a wah-wah, because as soon as you use pedals, you sound like you’ve got a mask.

When people ask me, “But how do you get your sound?” I say my sound is my heart, my fingers, and my emotions. It’s not like I need to have a package of ingredients. No, no, no, it’s not like that. You are the sound. Your emotions, your feeling, and your passion.

The intention was: What would a sound that’s combining Wes Montgomery, Otis Rush, and Gábor Szabó be like? Or a little bit of Jimi Hendrix with Paco de Lucía?

At this point were you still using the red Gibson SG Special that you’d played at Woodstock?

No, by that time I had moved on to two other guitars. I had one that kind of looked like Bob Marley’s guitar [a mahogany Gibson Les Paul Special], and then I went and got a Les Paul Custom, cherry red with yellow.

That’s because the one that I played at Woodstock, unfortunately, wouldn’t stay in tune. In the past I’ve said that guitar was like wrestling a snake, but really it was that the neck kept moving, and then the intonation changes drastically and pretty bad. So I got rid of that guitar.

What was your intention for your guitar tone?

The intention was: What would a sound that’s combining Wes Montgomery, Otis Rush, and Gábor Szabó be like? Or a little bit of Jimi Hendrix with Paco de Lucía? And that’s what I was doing with “Black Magic Woman/Gypsy Queen” and “Oye Como Va.” Eventually, though, I didn’t have to think like that anymore.

What kind of gear did you use to get the sound that you wanted? In your autobiography, The Universal Tone, you mention using a Boogie amp, but some say that you used a Fender Twin, possibly modified by Bob Gallien?

It was before all that. I was using two to three Twins, because I was copying the sound of Michael Bloomfield, Peter Green, and some of B.B. It wasn’t until ’72 that Boogies were created.

I also used a Marshall on “Hope You’re Feeling Better,” and that was a little different for me, because I wasn’t used to hearing the tone from my hands sound so brash and big.

Even though I’d heard Jimi and Eric Clapton, it’s very daunting to handle a Marshall full on. It’s like wrestling with a big, electric gorilla. So on “Samba Pa Ti” and all of that, I was still using the Fender Twin.

Bill Graham invited us to his office and played “Evil Ways” as he explained where the intro, verse, and chorus are. We weren’t used to dealing with songs like that

You didn’t have a lot of guests on the album. It’s the band plus Alberto Gianquinto on piano [“Incident at Neshabur”] and Rico Reyes on backing vocals and percussion [“Oye Como Va,” “El Nicoya”].

Yeah, I think we were more guarded with just the band in the beginning. Bill Graham had told us, “You don’t even know what a song is. You guys play a bunch of ass jams with no beginning and no end!” And we were like, “Wha?” He invited us to his office and played “Evil Ways” [written by Clarence Henry] as he explained where the intro, verse, and chorus are.

We weren’t used to dealing with songs like that. Gregg and I, we just jammed to stuff like the Jazz Crusaders. So it was Bill Graham and Alberto Gianquinto who made us make a song complete, and within three to four minutes instead of within 14 minutes. But it worked.

It would be great to hear stories behind some of the songs. Let’s start with the opening track, “Singing Winds, Crying Beasts.”

I remember quoting “Eleanor Rigby” by the Beatles, but not sounding like them. Gregg and Michael [Carabello] had created this mood, and I wanted to make my guitar sound like a violin and a lady crying in the night because she can’t find her baby.

What about “Black Magic Woman/Gypsy Queen”?

“Black Magic Woman” was played for the first time at a sound check in Fresno at a parking lot. Gregg wanted to do this Peter Green song, and I had heard of him a lot, but not that song. So when we started it off, I thought I should try a little bit of Wes Montgomery with a bit of Otis Rush. And that was it. “Gypsy Queen” is pure Gábor Szabó with a little Jimi.

What do you remember from “Incident at Neshabur”?

That’s the beginning of me wanting to be and sound like Miles, bending notes and getting all inside your heart. See, the beginning of it [sings the guitar riff] came from Alberto. He and I wrote the song, but he had lyrics which went. “Can you dig, can you do, can you do the pimp thing?”

By the grace of God, I see this creation right out there with the Beatles’ 'Abbey Road' and Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones

And the words at very end of the riff went, “Go ahead brother, right on.” When I heard that, I was like “Really? Okay.” The other part [sings the melody that takes the song into the second, meditative part] has two chords that are a bit like “Fool on the Hill.” I just took those two chords and played everything that I was hearing at the time.

It seems like it would be hard to release this type of album today and achieve the kind of commercial success you had. What do you think?

That’s a very good question. I think the times back then were a lot more expansive. Nowadays, people create words like alternative reality and artificial intelligence, and this generation maybe wouldn’t know what to do with an Otis Redding, Jimi Hendrix, or Miles Davis. In the ’60s, people were expanding their consciousness. Today, they don’t do that as much.

How do you see your creation 50 years later?

By the grace of God, I see this creation right out there with the Beatles’ Abbey Road and Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones. Not on top, not below. Right with ’em.

- Abraxas is available now on all formats, including vinyl, via Sony Legacy.