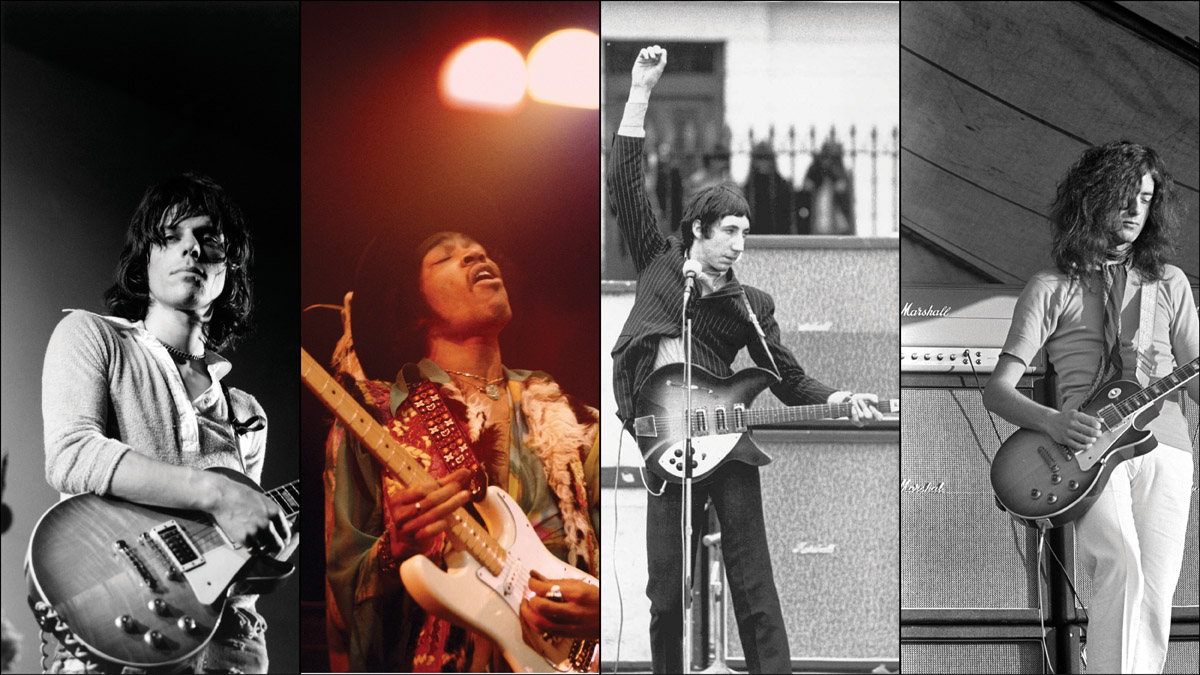

How Beck, Hendrix, Townshend, Page, and More Set the Template for Hard Rock Guitar in the 1960s

The progenitors of hard rock gave sound and shape to a divergent and ultimately diverse strain of rock and roll.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Like rock and roll itself, it’s not easy to pinpoint the origin of hard rock, its louder, noisier, and more provocative offshoot.

Driven by strong rhythms and dominated by loud guitars playing aggressive riffs with distortion, hard rock grew from the stylistic and tonal preferences of electric blues players like Willie Johnson and Pat Hare, and rock and roll guitarists such as Link Wray and Dick Dale.

The first blossoming of a hard-rock scene occurred in the late 1950s and early ’60s in Texas, Southern California, and, especially, the Pacific Northwest, where garage-rock bands – including the prototypical hard-rock act, the Kingsmen – churned out three-chord tunes like “Louie Louie.”

In this primitive state of its evolution, hard rock was a germ looking for a healthy host to help it thrive. It found several among the bands who arrived in the second wave of the British Invasion. The Kinks, the Who, the Rolling Stones, and the Yardbirds were among the main acts who cranked up their amps or plugged into a distortion box to give their guitars a harder edge.

Unlike their American garage-rock brethren, they approached it artistically, adopting its primal force to create a more musical – and in the onstage auto-destruction performances of the Who’s Pete Townshend – physical manifestation of their generation’s countercultural stance.

The fact that so many of those groups enjoyed hit records only served to advance hard rock into the mainstream, from which new acts emerged.

By the end of the decade, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, and Deep Purple were leading the way to hard rock’s future, while Black Sabbath represented the first splintering of the genre toward what would become heavy metal and, eventually, simply metal, with its own numerous subgenres.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But hard rock wasn’t merely entering a phase of popularity – it was also developing into an art form. Practitioners like Hendrix, Jimmy Page, and Jeff Beck used effect pedals to take their guitar tones to new realms, while Townshend wove his angst-ridden tunes into rock operas.

In this way, hard rock began to evolve, securing its future and laying new paths from which other strains, like glam rock and prog, would eventually emerge.

Jeff Beck

His inventive guitar techniques and use of effects established the template for hard-rock virtuosity and tone.

He came out of nowhere with a sound and style like no other. When Jeff Beck joined the Yardbirds in 1966, he took over from Eric Clapton, soon to be celebrated as no less than God for his fiery guitar playing with John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers.

Another guitarist might have gone weak in the knees having to follow in Clapton’s footsteps, but Beck was practical. “It occurred to me that it was a lack of dexterity or skill as a guitarist at that time that made me explore the weird sounds that I found I could make – feedback, echo, and the like,” he told Guitarist magazine in 2009.

“So I just delved into my brain box to find sounds that didn’t sound like a guitar. I used to listen to Alvino Rey, the legendary pedal-steel player, who would create vocal wah sounds with the guitar. Also Les Paul using slap echo and multitrack really caught my ear. It was the hippest stuff I’d heard at the time.”

Jeff Beck's developed a style of expanding the electric guitar using sounds and techniques and made it into something that was totally unheard of – and that’s an amazing feat, believe me

Jimmy Page

The effect on Beck was profound, and ultimately proved vital to the creation of hard rock. Infusing his sound with all manner of effects – including fuzz as well as the aforementioned feedback and echo – Beck weaponized his guitar tone, making it louder and more menacing than anything previously heard on record.

As much as his effects heralded the dawn of psychedelic music, they also made the guitar snarl, buzz, and scream in ways it hadn’t yet in pop music. And it certainly didn’t hurt that he had the chops necessary for the job.

As his pal Jimmy Page rightly noted, “His guitar style is totally unorthodox to the way that anyone was taught. He’s developed a style of expanding the electric guitar using sounds and techniques and made it into something that was totally unheard of – and that’s an amazing feat, believe me.”

Beck’s early Yardbirds hits provide ample evidence. His fuzz-tone effect is all over “Heart Full of Soul,” “Shapes of Things,” and “Over Under Sideways Down,” songs on which he delves into Eastern-influenced melodies that would become commonplace in psychedelic music.

But that was all a warm-up for late-1966’s “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago,” on which Beck shares guitar duties with Page, then the Yardbirds’ bassist. Together, they use their guitars to create a cacophony of sounds ranging from sirens to explosions, over which Beck lays down one of the fiercest solos of that or any other time in rock.

After parting ways with the Yardbirds, Beck continued to chase harder-edged sounds for 1968’s Truth, his solo album debut, using blues-rock as a template. Among that album’s highlights is “Beck’s Bolero,” an epic track recorded two years earlier with support from Page, future Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones, keyboardist Nicky Hopkins, and Who drummer Keith Moon.

Jimi Hendrix reportedly called it one of his favorite songs, and Duane Allman said it inspired him to take up slide guitar. But you don’t have to listen very hard to hear in that 1966 recording the future sound of hard rock.

Top Track: “Beck’s Bolero”

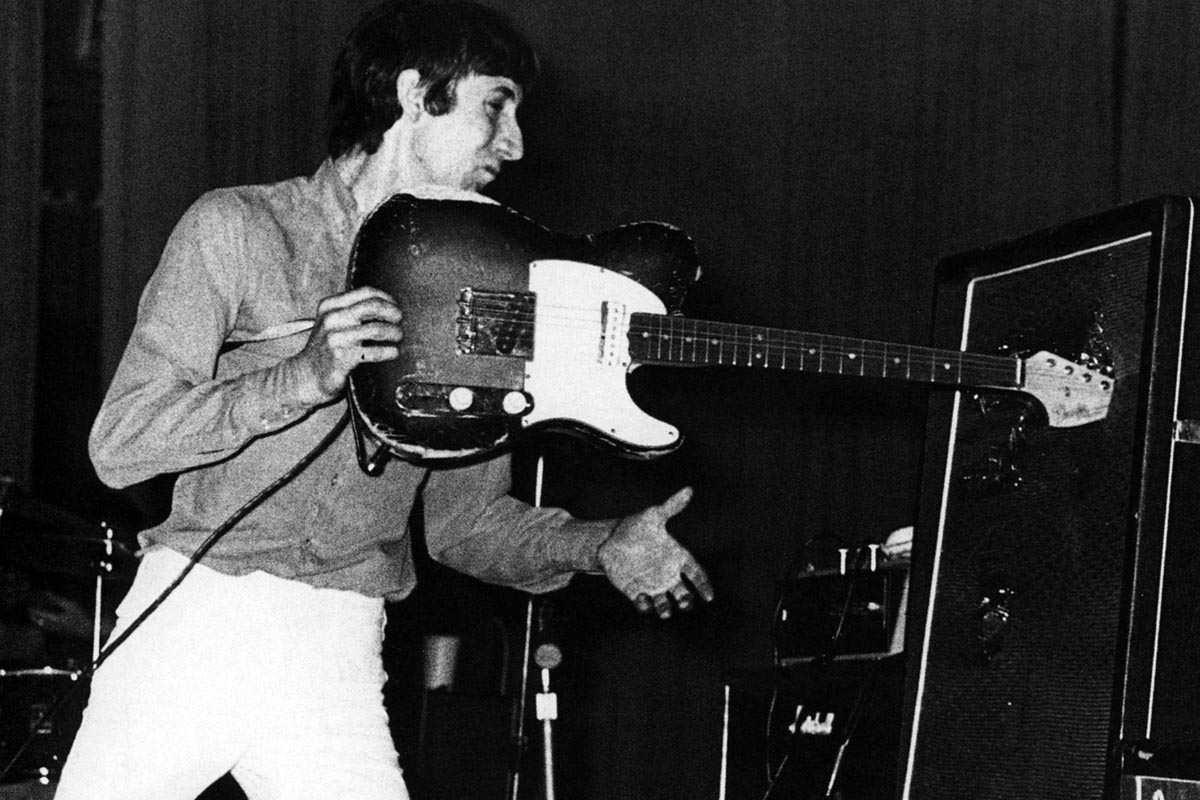

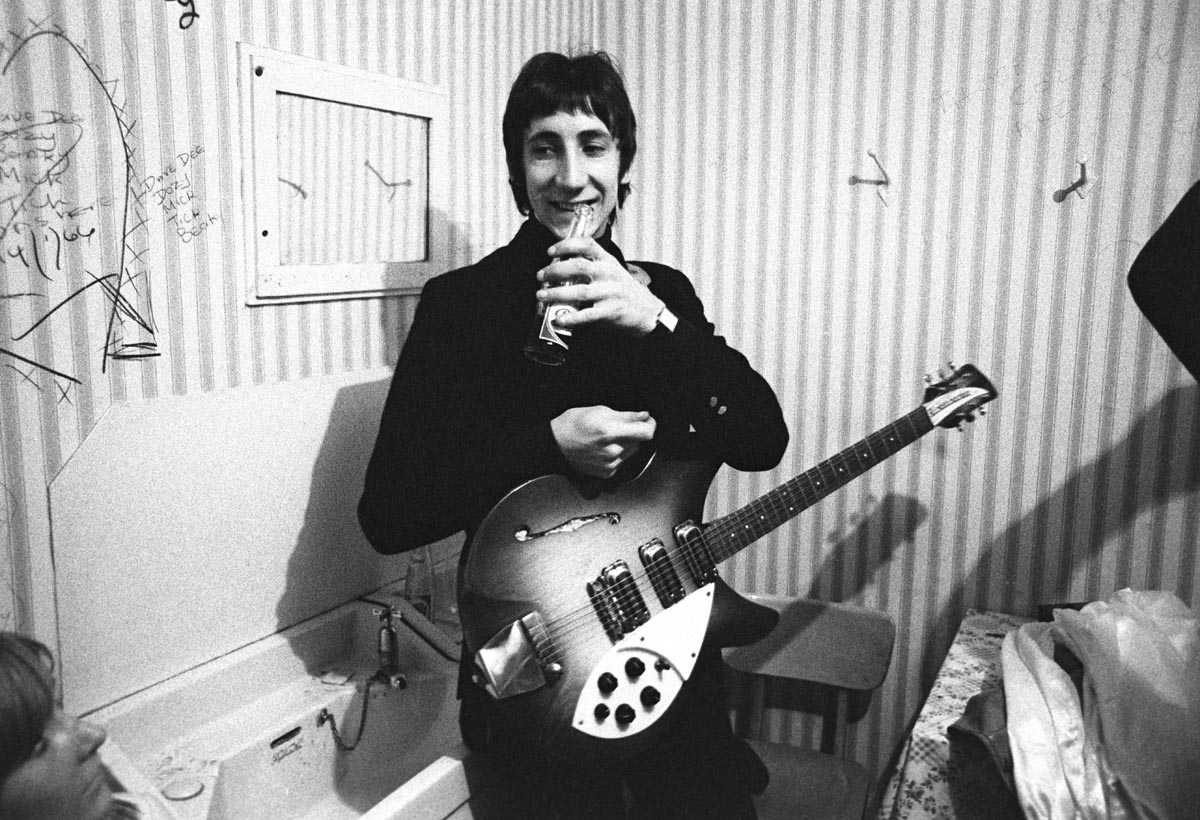

Pete Townshend

His combative guitar style, theatrical sensibilities, and thirst for volume defined the essence of hard rock. He was also behind the creation of every hard rock guitarist’s favorite piece of kit – the double stack.

No guitarist of the 1960s brought as much volume, aggression, or savagery to rock and roll as the Who’s Pete Townshend. Much of that is down to his use of distortion, feedback, and power chords, but it was also due to the sheer volume he would achieve onstage.

Indeed, Townshend was one of a handful of guitarists – including Ritchie Blackmore and Big Jim Sullivan – who pushed Jim Marshall to make his amps louder. And it was Townshend, along with Who bassist John Entwistle, who blazed the trail for the 4x12 double stack, now and forever a mainstay in hard rock.

But Townshend needed a stage presence to go with that big sound, and he got it by making his every move as big as possible: windmilling his arm to strum chords, springing skyward at key moments in a song, and, of course, destroying his equipment at the end of the show. Townshend pushed the limits of rock and roll to make it louder and more visceral than ever.

“A lot of it was posing, trying to drag something out of the band that it was resisting,” he said in 1990. “And as I got louder, John [Entwistle] got louder by inventing the 4x12 speaker cabinet, which he did with somebody up at Marshall.

“Then I got a 4x12 cabinet and put it on a chair, so then he invented the 8x12 cabinet to get louder than me, and then I invented the stack by getting two 4x12s and stacking them up. [Marshall] were nagging me about the fact that the top cabinet was shifting and was going to fall off and get damaged, and I just said, ‘So what?’ and knocked it over! There was a tremendous kind of arrogance.”

While other guitarists worked hard to prevent feedback, Townshend embraced it. In a posture dubbed the Birdman, he would stand with his arms outstretched to either side, his guitar hanging from his neck as the feedback howled to a peak. Though he was not the only guitarist of the time to use feedback, he made the most theatrical use of it.

“I believe it was something people were discovering all over London,” he said. “These big amps that Marshall were turning out – you couldn’t stop the guitars feeding back!” Like Beck, Page, and Clapton, he turned his guitar solos into emotionally packed moments that lifted the song to even greater heights, even if it meant playing just one note, as he did on the Who’s 1967 hit single “I Can See for Miles.”

Coming at a time when those three guitarists were taking guitar virtuosity to new levels, was Townshend’s solo an anti-hero move? “I’m sure it was a kind of defense mechanism,” he admitted. It helped him not only survive but also cut his own path, leading the way for future guitarists from Brian May to Pearl Jam’s Mike McCready.

Top Track: “I Can See for Miles”

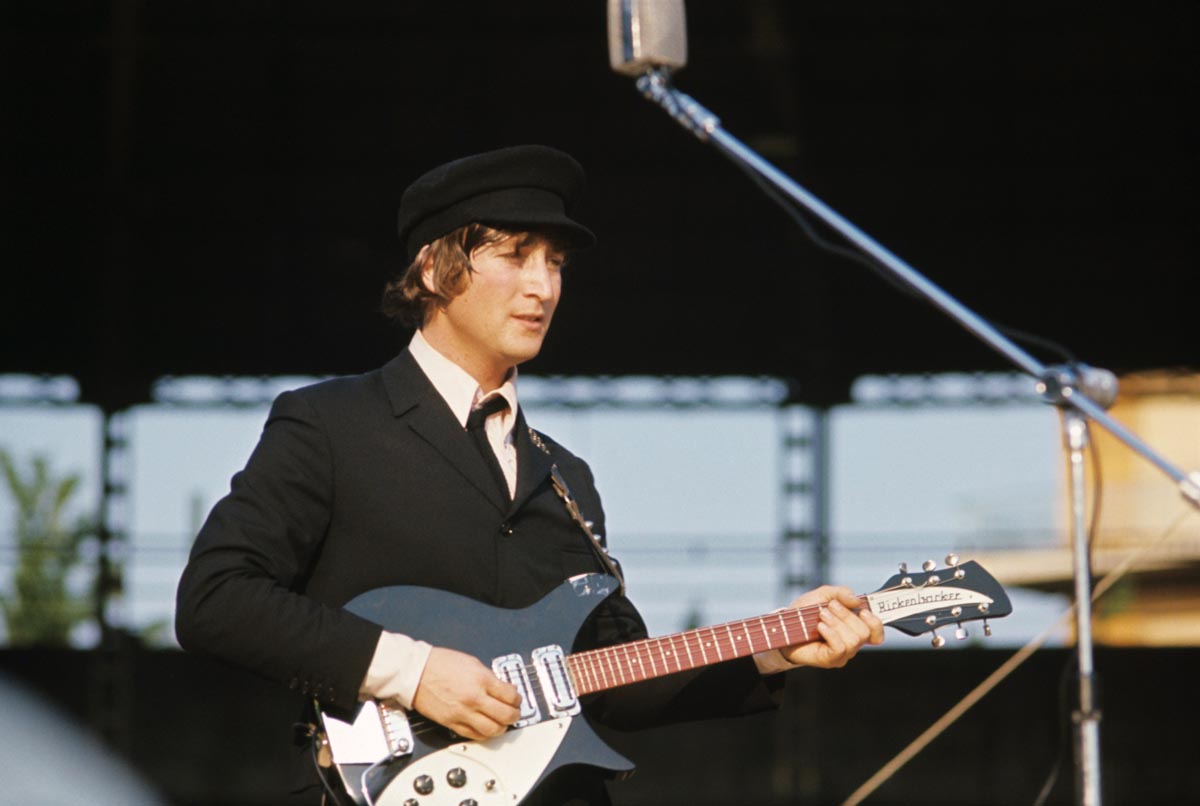

John Lennon

As a member of rock and roll’s most popular band, he helped lead the pop masses to harder fare.

Sure, the Fab Four’s diverse musical history has blurred over time into a miasma of nostalgia, highlighted by pop fare like “Hey Jude,” “All You Need Is Love,” and “Strawberry Fields Forever.” But the Beatles could get as heavy as the Who, Cream, and the rest of the 1960s acts for whom they paved the way.

Consider John Lennon’s “Ticket to Ride,” a 1965 rocker that featured Ringo Starr’s heavy drum rhythms and a circular guitar riff performed by George Harrison on his Rickenbacker 360/12 and Lennon on his Fender Strat, all of it girded on the verses to Lennon’s low, droning guitar notes.

Later that year, Paul McCartney plugged his bass into a fuzz box for Harrison’s Rubber Soul track “Think for Yourself” and turned it into the rattiest-sounding lead guitar. But all of that was just a warm-up for 1968, when the Beatles would release some of the most aggressive rock tracks of their career.

First up was the 45-rpm version of Lennon’s “Revolution,” a raucous rock-and-roll number featuring some of the dirtiest fuzz-guitar tone heard up to that time. Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick later revealed the sound was created by plugging Lennon’s and Harrison’s guitars straight into a pair of mic preamps connected in series and overloading them to just below the point of overheating the mixing console.

The release of the band’s White Album that November revealed even more hard-rock gems in the form of Lennon’s chaotic “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide (Except Me and My Monkey)” and McCartney’s “Birthday” and “Helter Skelter.”

Among the four Beatles, Lennon in particular would continue to explore rock’s more aggressive side in his early solo years and with the Plastic Ono Band on tracks like “Cold Turkey” and “I Found Out.”

Top Track: “Revolution”

Jimmy Page

He single-handedly established the original template for hard-rock guitar tone, production, and showmanship.

Along with Hendrix and Beck, Jimmy Page is part of the triumvirate of guitarists who did the most to forge the sound of hard rock in its formative years. Like Beck and Hendrix, he brought a new level of aggression and virtuosity to guitar playing within the rock idiom, as well as a talent for crafting infectious riffs and sculpting tones unlike anything heard before.

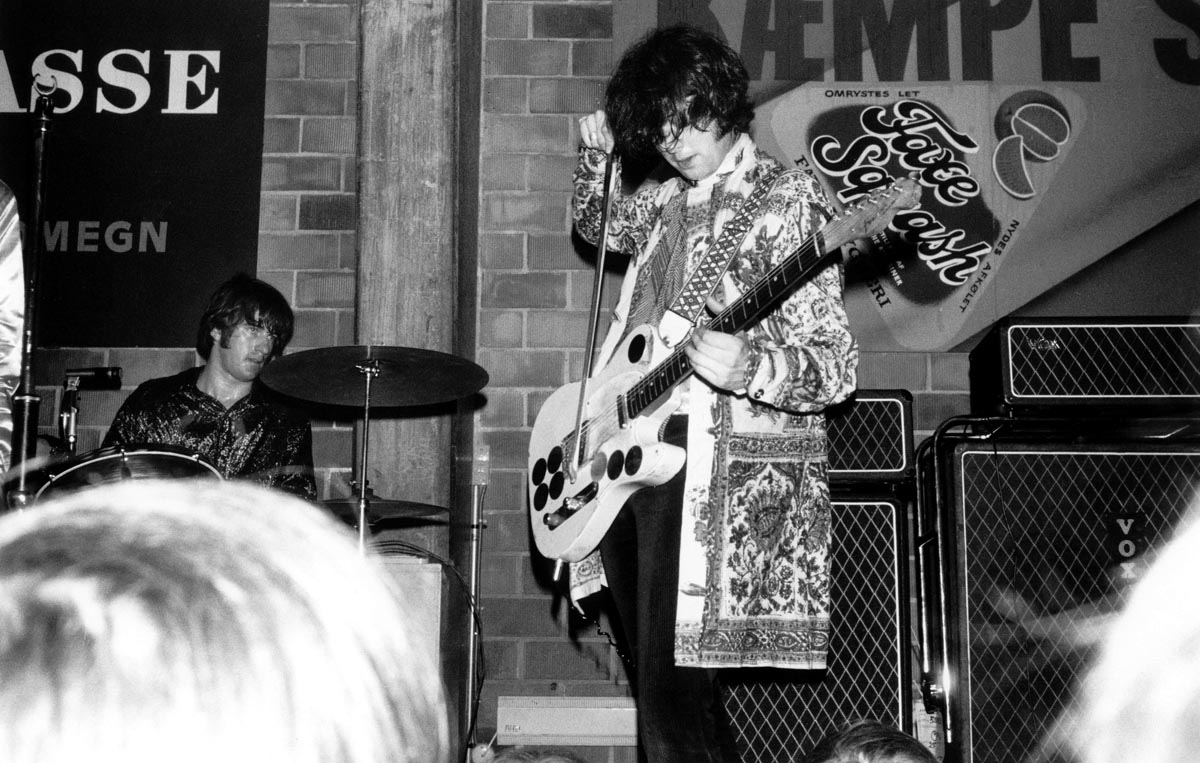

After several years of anonymous studio work in the early to mid 1960s, Page came into his own with the Yardbirds, where he briefly shared lead “stereo” guitar duties with Beck in 1966.

Their dueling guitars can be heard on “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago,” a hard-rock milestone that also served as a proto–heavy metal track. When Beck left later that year, Page assumed a more prominent role, shifting the band’s focus from singles to albums, and introducing longer tracks like “Dazed and Confused,” on which he soloed and improvised during an extended middle section.

Taking a violin bow to his guitar for the 1967 track “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Sailor” might have been seen as gimmicky, but Page was thrilled with the variety of sounds he could produce, and it made a great bit of showmanship onstage.

But it was of course in late 1968, with Led Zeppelin, that Page’s talents came to fruition. As the band’s guitarist, producer, and main songwriter, he pushed their music to new extremes by experimenting with effects like the Maestro Echoplex and Sola Sound Tone Bender, and using distant mic placement to give more depth to his guitar.

His remarkable gift for riffage resulted in a slew of Zeppelin classics, from “Whole Lotta Love” to “Kashmir,” and established the template for hard rock anthems.

The fact that it worked at all was down to his impeccable ear for tone and choice of gear. To that end, Page wielded a ’59 Fender Telecaster gifted to him by Beck, a ’59 Les Paul Standard, and a ’61 Danelectro 3021, among many other electric guitars, and famously used a heavily modified Supro Conquistador amp on Led Zeppelin’s groundbreaking debut album.

From studio production to gear choice to songwriting and stage work, Page revealed the world of hard rock as a place ripe for experimentation, moving it beyond its blues-based origins to embrace folk, Eastern, and even orchestral music.

Top Track: “Whole Lotta Love”

Jimi Hendrix

From his gear to his sound to his style, he reshaped rock and roll and demonstrated the full scope of what could be expressed with an electric guitar.

Jimi Hendrix so completely changed the music landscape in the late ’60s that it’s difficult to conceive how any guitarist of the last half century couldn’t have been affected by him or his music.

Without Hendrix, how would guitars with locking trems have been developed? What about high-gain amplifiers and effects pedals? Hendrix had Marshall amps, the Fuzz Face, the Cry Baby wah, and the Octavia that Roger Mayer invented.

He played a right-handed Strat that he flipped over so he could play it left-handed. For his short-lived career, it was all he needed to create game-changing music. He took the blues styles that he was well acquainted with to a whole new level via his use of distortion, feedback, and sheer volume to create sounds that dovetailed with everything that the psychedelic ’60s represented.

Whether it was drugs, a generation of kids facing a war in a distant part of the world, social upheaval, or whatever else, it didn’t matter much when you were 14 and first heard “Foxey Lady” or Purple Haze” detonating the airwaves. You just knew that this was really something else, and that things had changed big-time.

As Joe Satriani put it, “The first thing that really flipped me out was hearing ‘The Wind Cries Mary’ on the radio. Before that, I was a drummer, and I started from watching the Rolling Stones and the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show. But as soon as I heard Hendrix, that was it.”

One of the most fascinating things about Hendrix is how he evolved from a blues and R&B player to become the world’s most celebrated rock guitarist in such a relatively short amount of time. After a stint in the army (he was discharged in 1962), Hendrix worked with R&B artists, including the Isley Brothers and Little Richard.

Frustrated with the R&B scene, he established himself in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village and started his own outfit called Jimmy James & the Blue Flames.

Hendrix seems to have used the Blue Flames during their three-month tenure at the music hot spot Cafe Wha? to work out early versions of “The Wind Cries Mary,” “Third Stone From the Sun,” and his renditions of “Hey Joe” and “Red House.” His sound was evolving as well.

As blues guitarist Michael Bloomfield described it, “I can’t tell you the sounds he was getting out of his instrument. He was getting every sound I was ever to hear him get, right there in that room with a Stratocaster, a Fender Twin, and a Maestro Fuzz-Tone. He was doing it mainly through extreme volume.”

With his songs and sound together, Hendrix exited the Blue Flames, and on September 24, 1966, he headed for London to work with producer Chas Chandler – former bassist for British rock band the Animals – and ex-Animals manager Michael Jeffery. Hendrix then enlisted bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell and changed his name to Jimi.

From then on, it was the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and between 1967 and ’68, they would record three studio albums: Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold as Love, and Electric Ladyland.

Jimi then switched gears, and with Billy Cox on bass and Buddy Miles on drums, the Band of Gypsys live album was recorded on January 1, 1970, at the Fillmore East in New York City. It was released March 1970, and plans were in place for the next album when Jimi died on September 18, 1970. We’ll never know what might have been, but Hendrix made a mark on hard-rock guitar playing that echoes to this day.

Top Track: “Machine Gun”

Wayne Kramer and Fred “Sonic” Smith

Combining defiant, high-volume rock with jazz and a take-no-prisoners stage show, they heralded a new level of intensity and showmanship.

In a music scene teeming with talent – including Ted Nugent, Bob Seger, and Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels – the MC5 burst to the forefront of Detroit rock and roll in the late 1960s with a countercultural stance against institutionalized racism and twin guitars blazing through 100-watt Vox Super Beatles.

Guitarists Wayne Kramer and Fred “Sonic” Smith forged a dual-guitar blast that combined bare-bones rock and roll with the avant-garde eclecticism of free jazz.

That fusion was loud and clear on Kick Out the Jams, the MC5’s live debut, rallying a wave of hardcore rock fans behind the emerging hard-rock scene at a time when rock and roll was splintering into offshoots like heavy metal, acid rock, and progressive rock.

In that respect, the MC5 were among the bands most responsible for defining hard rock’s extreme sound, rebellious attitude, and adventurous spirit.

That it happened at all was down to Kramer and Smith, teen guitar-playing friends who cut their teeth on the early rock and roll of the Ventures, Dick Dale, and Chuck Berry. Each had his own group, but in 1964, as their bandmates began exiting for college, they joined forces with singer Rob Tyner, bassist Michael Davis, and drummer Dennis Thompson and dubbed themselves the Motor City Five.

With the purchase of those Super Beatles, the MC5 quickly became one of the city’s hottest acts. “They made us the loudest band in Detroit, a title we wore with great pride,” Kramer said. “And we discovered we could push the sound beyond what had previously been accomplished with electric instruments.”

Kramer and Smith played a number of guitars over the group’s early years, the most iconic of which were Kramer’s American flag–finished Fender Stratocaster (hot-rodded with a Gibson humbucker in the middle position) and Smith’s white Mosrite USA 65-SB.

The MC5’s initial run was brief – they disbanded in 1972, and Smith died in 1994 – but their intense guitar-driven music paved the way for punk and grunge. “This is not music for the faint of heart,” said Kramer, who continues to perform and compose for soundtracks. “This stuff rocks hard.”

Top Track: “Looking At You”

Keith Richards

He turned electric guitarists on to fuzz by plugging his Gibson Firebird VII into a Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone for the Rolling Stones’ 1965 hit “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” adding a level of intensity that ultimately helped transform blues rock into hard rock.

Need more? Check out Keef’s raging fuzz-and-feedback-drenched playing on “Citadel,” from Their Satanic Majesties Request, or his hard-as-nails acoustic work on “Street Fighting Man.”

Top Track: “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”

Dave Davies

His use of power chords on early Kinks songs like 1964’s “You Really Got Me” and “All Day and All of the Night” turned rudimentary chording into ear-catching lead work.

Davies also created early hard rock’s definitive guitar sound by slashing the speaker of his small Elpico amp with a razor blade to produce blistering distortion, while using the combo itself as a preamp into his Vox AC30. Small wonder a gear-modification innovator like Eddie Van Halen was a Kinks fan.

Top Track: “You Really Got Me”

Eric Clapton

Between his brief stint with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and his mid-’70s solo career, Clapton took a break from traditional blues, formed Cream, and forged the kinds of heavy guitar tones and incendiary lead playing that defined hard rock’s bluesier side.

But his work during this time, cut largely with his 1964 Gibson SG repainted by Dutch art collective The Fool, drew equally from jazz, imbuing hard rock with a sophisticated modal interplay seldom heard before in rock.

Top Track: “Crossroads”

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.