Chester Kamen on Live Aid, Impressing Madonna and Falling in Love with the Ugliest Amp in the World

Kamen talks session life and explains how he does things a little differently with Chester Kamen and the Loves.

Chester Kamen has played with everybody. Well, not everybody, but you can count the likes of David Gilmour, Madonna, Roger Waters, Duran Duran and Seal among his collaborations.

His big break as a session player arrived the early ‘80s as Bryan Ferry brought him into the fold.

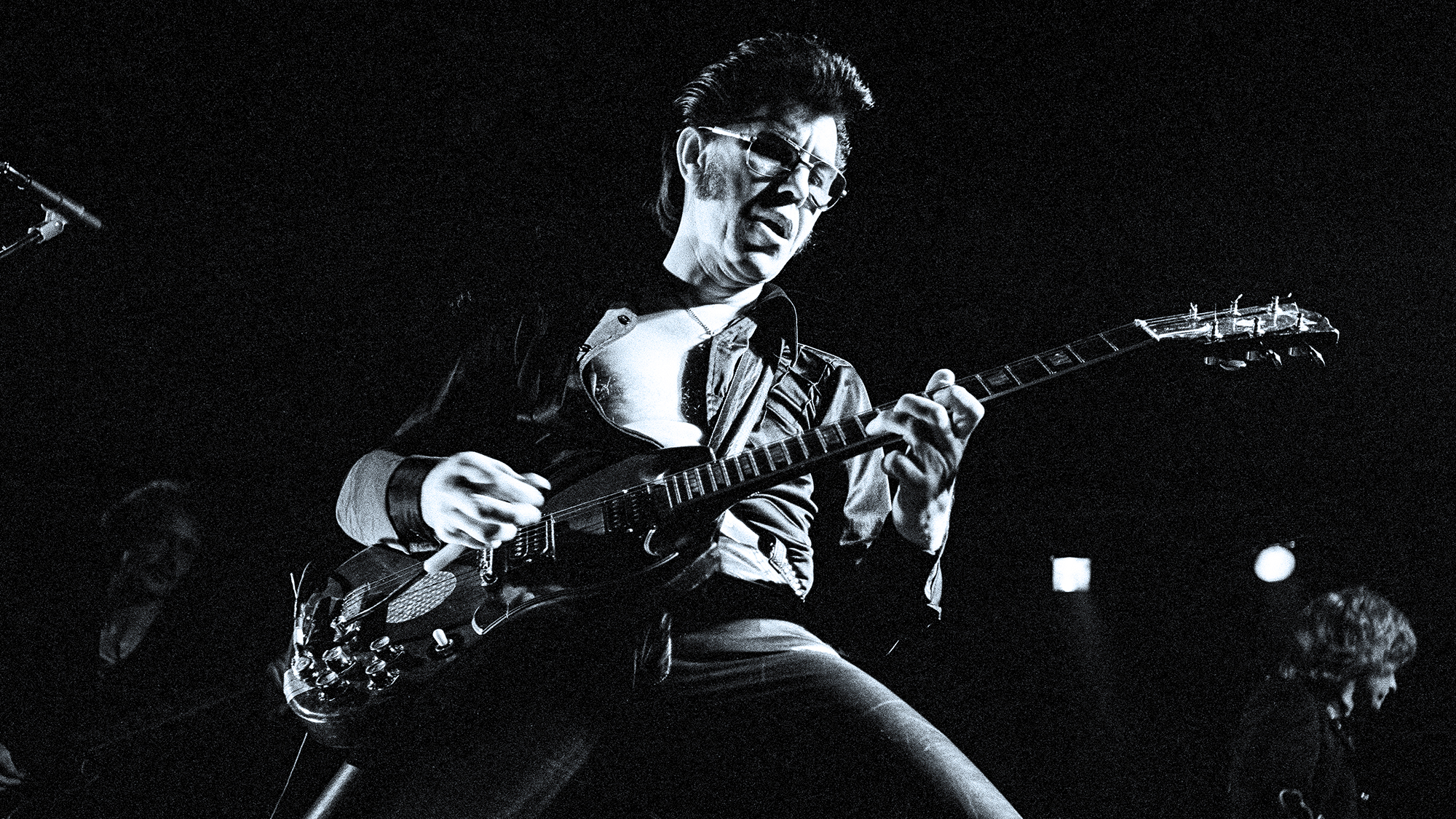

Though that in itself proved that Kamen’s ability with the guitar was pretty much unimpeachable, it also proved that if you had great chops and a pair of white chinos the decade belonged to you; check out his solo during Bryan Ferry’s cover of “Jealous Guy” at Live Aid, a moment in which Kamen was playing lead and Gilmour rhythm. That’s not a bad jam for a sunny afternoon at Wembley Stadium.

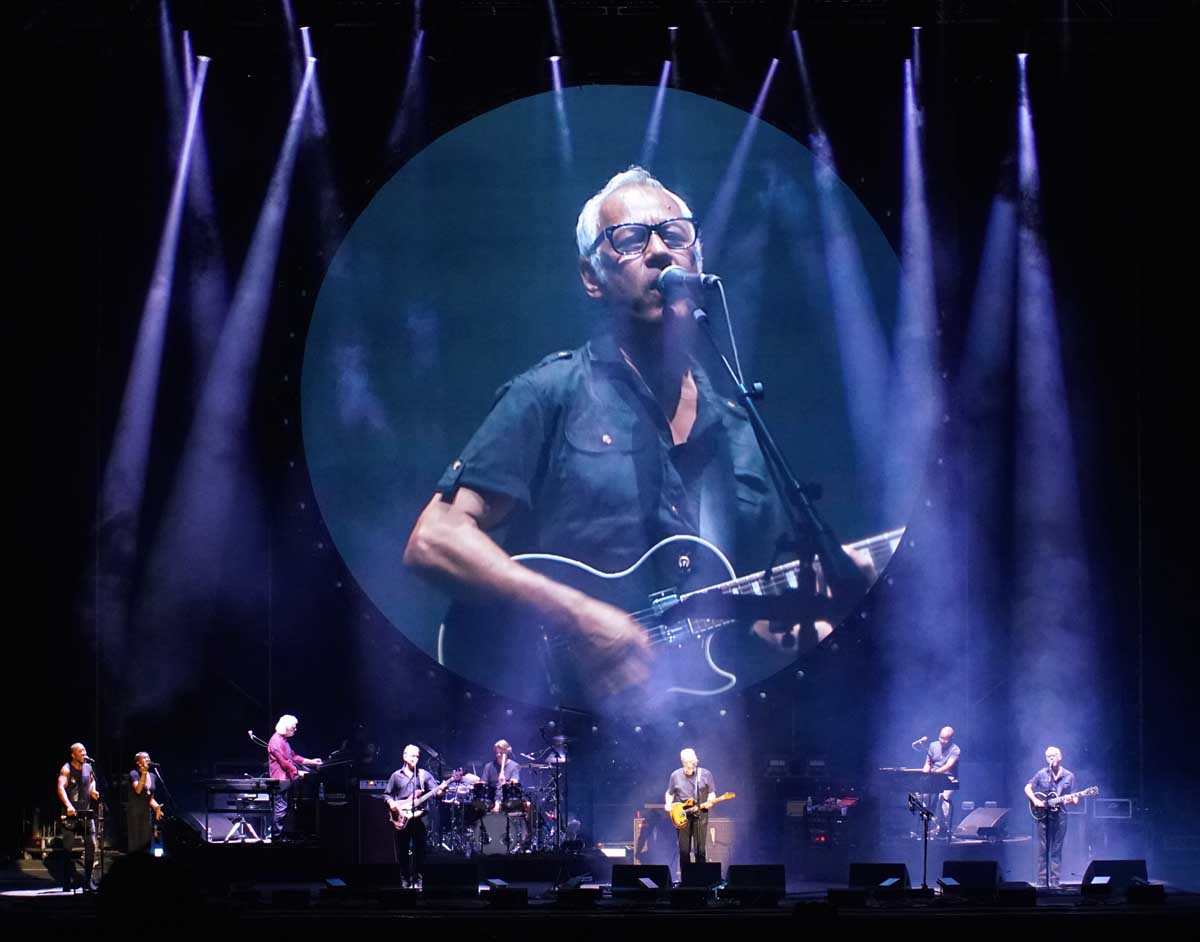

Of course he would then go on to join David Gilmour’s touring band. These kind of gigs just happened by accident, says Kamen. All he ever wanted was just his own band, but then what else are you going to do if the phone keeps ringing with gigs like that?

“It was never a plan and it was all word of mouth, the whole lot,” he says. “I had no agent, no manager and no intention to be a session player. I always wanted to be in a band. I just wanted to be a guitar player in a band, making records. That was what I wanted to do, but once the phone starts going. “Yeah, I’ll do it.” And on it goes…”

And on it went. But Kamen does have his own band. He’s got two, in fact. He’s on the phone to talk about Chester Kamen and the Loves’ fifth album, Americanized, but he’s also got the Twins, an up-tempo rock trio with a jazz sensibility that sees Kamen joined by Dale Davis on bass and Hugo Degenhardt on drums. All three sing in harmony.

If the Twins skew avant garde, the Loves’ sound is in-the-pocket, a love letter to eighth-note rock rhythms, a record of feel-good strut and some sizzling guitar playing. Seriously, the tone on “Fine Lines” is one to luxuriate in.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Americanized was recorded at drummer Steve Monti’s home studio before being polished off and mixed at Chenzo Townshend’s. But as Kamen explains, the record all started around the kitchen table with Michael Cahill and a couple of guitars.

Maybe that’s the best place to start - but the story will take some turns, winding back onto the stage at Wembley, where he played through the ugliest guitar amp in the world - an amp that defies the odds in being so crucial to his sound.

How did Americanized come together? Do you need everyone in the room for it to happen?

Absolutely not, no. Generally with the Loves, it's Michael Cahill and myself who are writing the songs and occasionally there will be a band song that will have kicked off from a jam.

It’s Michael and I, really, and it varies from me giving Michael a set of lyrics and then him going away and then fashioning a basic song, and then coming back to me, and then the two of us finishing it off.

The two of us sat around a table and we never went into the studio until the song was finished. We just sat around the dining table with a couple of guitars. That’s how we did it.

The songwriting can be a little more relaxed in that setting.

I have spent so many years doing it the other way round, where you go into the studio, you work on an idea, you build it up, and then somewhere further down the line the lyrics need to be written and all that kind of thing!

It taught me a lesson that I really didn’t want to go into the studio anymore without the songs being finished. When the songs are finished, it can all happen very quickly. You can knock out an album in two weeks and mix it in the third week.

We were still trying to make it sound like a live band. 'Call Me Back' was done all live. If anything went wrong, we didn’t patch it up. We just shouted, 'Stop! Do another take! I really liked that

How did you capture that energy on tape?

This album was done very strangely, in that Michael and I were writing in the living room with two guitars, then we’d go into the rehearsal room and play them as a band, and then when it came to actually recording them we didn’t do them live; I programmed them up on my old-fashioned sequencer.

All the songs were programmed on an old ‘80s sequencer/sampler thing, a drum machine, and then we put down a guide vocal and rhythm guitar with that drum box. And then the band played on top. So it was a manufactured record, unlike the previous one.

That’s funny, because it sounds all live.

We were still trying to make it sound like a live band. The album before, Call Me Back, was done in the studio, all live. If anything went wrong, we didn’t patch it up. We just shouted, “Stop! [Laughs] Do another take! Do another take!” And it was great; I really liked doing that.

Is that something you enjoy as a session player - the pressure of the take?

That’s definitely a part of the session thing. Session playing is a different kettle of fish. In the old days - and when I say the old days I am only talking about the ‘80s onwards - it was all about putting down a take, doing the song from start to finish, and then of course there was no sampling, or the sampling was very primitive.

For me, sessioning was always about trying to get that entire performance, but as soon as the computer came in it really didn’t matter.

Do you think we have lost something by having that technological safety net?

Well you definitely lose a bit, because what happens nowadays is you don’t go, "That’s great, I’ll never get it quite as good as that.” [Laughs] You kind of go, "No, do it again. We can make it perfect. We can make it perfect. Do it again.”

You lose a little from not having that sense of the high-wire in your performance, yet gain from having the option to do it again with more feeling.

Yeah, that’s right! You can also play more freely if you know you can do it again and again. It frees you up to experiment in a way. If you are a bit tight - and you often are in a session situation - you have a tendency to play safe if you only have got one or two takes.

What did you use on Americanized?

Every single guitar and pretty much every single bass started off with the signal being sent into what was essentially a Colorsound Overdriver, circa 1970, and then into a Hughes & Kettner Crunch Master. The Crunch Master is effectively an amp in a box.

It’s a full amp. It’s got a preamp valve and a power amp valve, and what you are taking out the back of it is a speaker-emulated signal, the type of signal you would take out the back of a Palmer Speaker Simulator, so it’s like a line version of a speaker output as opposed to just a line out.

Because we were doing it in Steve’s home studio, one, it was completely under control, and two, the plan was to then, at the end of the recording process, send all of the guitar parts out to a live room of amplifiers. And that’s what we did when we went to Chenzo's studio.

I went then down there, sent all the guitar signals out to the live room into a Hiwatt and maybe a Marshall, maybe a Fender, and so that set the room off, and then you just rerecord that and add it to the mix.

The solo in “Fine Lines” has a lovely tone. Was that the Colorsound? It sounds a little like a Triangle Muff?

Funnily enough, I do have an old Triangle Muff - not even a Muff, it’s a Guild Foxey Lady, which was what the Triangle was based on, I think. But I didn’t use that. It would very likely be the Colorsound Overdriver, or a version of it because I had a few clones built.

I don’t know if you are familiar with the Colorsound but if you drive it full-tilt it becomes the best fuzz box that ever was. One thing I love about the Colorsound Overdriver is that it will not live on a pedalboard with other pedals. Nothing can go after it. Not a single pedal, because it seems to just blow them all up.

What about amps?

Amps are funny old buggers. I have got an old Peavey, and I bought it in 1982, and here I am in 2020 and I have still got it. And it is a really weird thing, because when I look back, say for instance, Live Aid, when I did Live Aid with Bryan Ferry. I had the Peavey and the Selmar 2x12.

When I went out with Gilmour on the last tour I had the same Peavey, [Laughs] and the same 2x12. And that’s what? Nearly 40 years? And there it is, the same blinking amplifier.

I used to use that amplifier in the studio all through the Bryan Ferry years and it is a really weird amp. It is often described by people who give it a go as the worst amp they’ve ever heard! [Laughs]

Which model is it?

It is a Peavey MX. It is a part of the VTX series. It is a very weird amp, I’ve got to tell you. It is like the Music Man HD Series; it has a transistorized front end into a 4x 6L6 power section. It was a complete hybrid, back-to-front kinda thing, and yeah, it is a weird one. Like all big-stage amplifiers it doesn’t really get going until you turn it up. And people start running out the room.

Oh yes, an amp that you look at and immediately try to forget having looked at it.

Guy [Pratt] called it the ugliest amp that ever lived, and in many respects he is right. It is pretty damn ugly.

But it sounds good?

What you are dealing with is a power amp section of four 6L6s with very big transformers. That power amp section is second to none. It is a beautiful thing, so when you plug into the clean channel and turn it up, you are virtually putting your guitar into this beautiful, glassy thick section and it is quite something. But, but! If you try and play it quietly it sounds horrible. [Laughs] Really horrible.

But isn’t that something that we maybe don’t talk about enough? That we have to learn to play the amplifier?

Absolutely. You’re dead right. And you said it there: you have to play the amp. In a way, for me, the guitar is like the mouth of the saxophone, but the guitar on its own is not much - it’s only a bit of it. I know exactly what you mean. That said, that Peavey… [Laughs] Somehow it keeps getting used!

But you know the thing, unlike a Marshall, which is a one-trick pony, the Peavey in that period was an attempt by the amp manufacturers to get an amp that could do many things. Switchable channels and blah blah blah.

Well, funny you mention volume, you’ve got to learn how to play with volume, too.

Yeah, that’s right. That Peavey, like I say, is a little too loud for clubs, and nowadays I'm using 50-watt Marshalls in a club, and even that is a bit too loud, or at least it is with my 50-watters, which have been doctored.

But I’ve got to play over a drummer. If a drummer goes, “Whack!” there is no point in me making 15-watt Super Champ noises - I’ve got to be able to compete and be on a par with that drum kit.

And bass players, unbelievably! Bass players, in general, even in little club gigs, show up with 400-watt rigs. The times I have tried to play quietly, it hasn’t quite worked ‘cos I have been at the squashed end of the amplifier.

Bassists are always turning it up!

Bass players are always turning it up and the only one it worked for was Jack Bruce. Jack Bruce was probably a lot louder than Eric Clapton, but he forced Clapton - forced Clapton! [Laughs] - to run that Marshall where the sound lay. There’s the lesson.

You know what it's like, you play a Marshall 100-watt, especially one that does not have a master volume, all the sound lies right at the top end. It’s a beautiful thing, especially with a Les Paul. You turn it down slightly on the guitar, with the amp on number 9 or number 10, and it is a beautiful clean sound, because it is very rich and grainy. But, it is bloody loud.

Do you prefer a smaller amp in the studio?

Yeah, I do use the Fender Super Champ quite a lot in the studio. But also whatever’s to hand. Sometimes you can get a really, really odd amp and it will work really well, like an HH or something, and you start to think, 'That is absolutely amazing. How did I get that clank?’ Added to that is that some of my favorite guitar players, absolute favorite guitar players, use transistorized weirdness.

But then you just have to trust your ear, not the name on the amp.

That’s right, and funny enough, going back to the new Loves album, all the guitar sounds came through the one Hughes & Kettner DI thing, which is actually nothing other than a sort-of valve amplifier, but it doesn’t sound like any one valve amplifier in particular. What it does is, you put your guitar into it and it sounds like your guitar.

What guitars were you using?

That’s another thing with that album, all of my guitars on that album are one guitar. I didn’t use my guitar collection, just one. And it was the same with Michael. Michael had a Telecaster. I had the Les Paul Custom, and that was it. There is maybe a little strummy acoustic stuck in there somewhere but essentially there’s nothing else on there.

Jan Ackerman was a huge, absolutely huge influence on me, and he used a transistorized Fender - what was that all about?

You mention guitar heroes. Who were the big ones for you?

The ones who really shaped me as a player, funnily enough, are all Les Paul Custom players. Jan Ackerman, huge, absolutely huge influence on me, and he actually used a transistorized Fender - for God’s sake! [Laughs] What was that all about?

Who else? [John] McLaughlin for a brief period, but just a brief period, and also when he was using a Les Paul Custom on the first Mahavishnu album. Hendrix, obviously. Hendrix was inescapable. And Clapton for the years that he was with Cream, and just after, but no further than that.

Which sessions did you learn the most from?

Well I learned a massive amount from Bryan Ferry. The thing about Bryan was he would just say, “Just respond. Whatever you hear, just respond to it. Any ideas, just let them go.” And so I was able to play without fear of making a mistake.

With Bryan, anything I could think of I just had a go at. I guess I was lucky in that respect, but that was the way I was playing anyway, and I was very used to tape recorders because I grew up with tape recorders. Alongside the guitar, the idea of just making music straight to a tape recorder was just part of my life.

Is it important in sessions that you are given that freedom?

Definitely. And it was something that I was obviously suited to, having a completely blank page. Some players are very good at being a rhythm guitarist in a session but I was never that great at that. I was all about the wild and wacky idea that no one else would think of.

What was Madonna like?

I played on Like a Prayer. That was really good, but that was a difficult bunch of sessions because Madonna was always like, “Impress me!” [Laughs] “What have you got? Impress me!” So that was quite intimidating.

It was a funny situation because I flew over to America with the Squier [JV] Strat which I have used ever since ’82, ’83, and when I arrived there and plugged it in at the studio, it was about as bad a hum as you can get on a Stratocaster.

I got to those sessions with a guitar that was making an awful humming noise and I was kind of embarrassed throughout the entire sessions. It was quite nervy, but, still, a lot fun. A lot of fun!

Would Madonna tell you what she wanted?

Not while I was playing, no. When I was playing, Pat Leonard was producing those sessions and she was more like, “Impress me! Impress me!” But that was more of a performance thing, a fun thing. It wasn’t a case of her sitting down and musically saying 'This is to go there and that is to go there.' That was more Pat’s domain.

Are you a better player for doing sessions?

That’s a very interesting question, and quite a difficult one to answer because I am not sure whether it did or not. I’ve got a million, squillion little bits, and there’s not one that I would call a definitive performance, whereas, if I had had a career in a band it would have been much more definitive.

Each performance would be more recognizable. I listen back to a record and I go, 'Yeah, well I can hear loads of little bits but in many ways it doesn’t feel like it is mine.'

You can look at it at an angle, from a little bit more distance than if it was all yours.

Yeah, that’s right. With the band I can listen back and it is much more straightforward. It is me standing there doing my thing. Still with the Peavey! [Laughs]

- Chester Kamen and the Loves' new album, Americanized, is out now via Stoney Records.