“Mick Taylor would play the top lines. Keith Richards would write most of the songs... Once, Keith said, ‘You play too f*cking loud. I can’t work with you in the room right now‘”: Andy Johns on the Rolling Stones' turbulent Exile on Main St. sessions

Though the late engineer had already worked with George Harrison, Paul McCartney, Free, Eric Clapton, and Led Zeppelin, he saw what would become the Stones' masterpiece as “the most important project” he'd ever taken on

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This interview with the late Andy Johns was originally published in the May 2010 issue of Guitar Player.

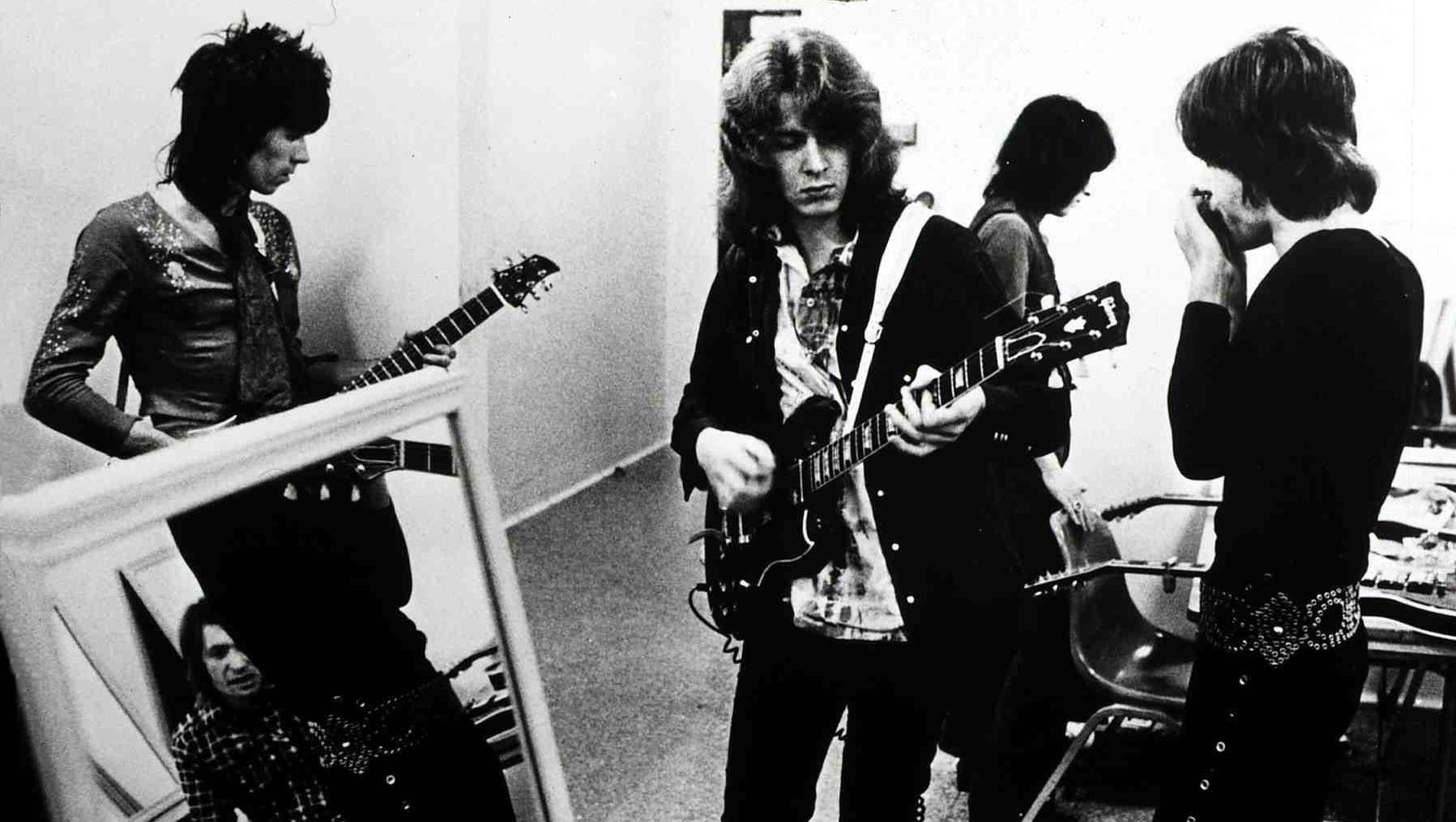

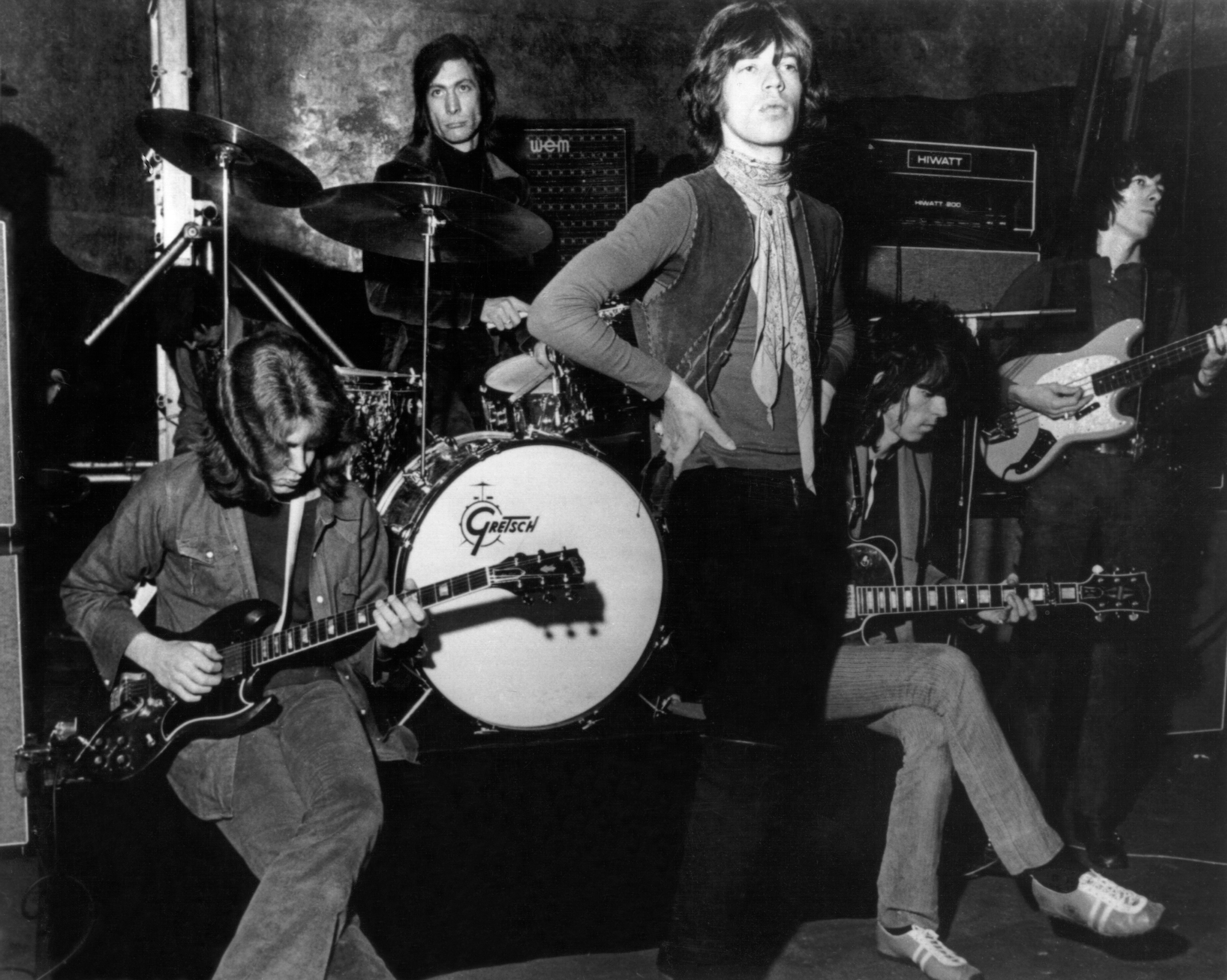

By 1972, producer/engineer Andy Johns already had a hall of fame caliber resume, having worked with Free, Blind Faith, Jethro Tull, Led Zeppelin, and many others. But it was then that he began work on a record that would come to be regarded as a milestone for everyone involved, the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main St. Now, with the reissue of Exile dominating the music biz, Johns looks back on the wild times of making that record.

What were some of the guitar rigs that Keith and Mick Taylor used?

“The majority of the time in the south of France they had these Ampegs that were very high wattage, I remember someone saying they were 300 watts, which seemed crazy to me because they were 2x12 combo amps, but they were jolly loud. I thought they were fantastic and I’ve never seen them anywhere else. At the time, the Stones had an endorsement with Ampeg. Some of the tracks on Exile were left over from previous sessions and those would have Fender Twins.

“Stop Breaking Down was a Fender Twin for both of them. 80 percent was the Ampeg setup. Keith had a very nice Tele and Mick would play a Gibson ES-335 and a Les Paul. He also had an Epiphone; I guess it was a Casino. Then we had a week off when Bianca Jagger was having a baby and when we got back all the guitars had been stolen – every last one. So Stu [Rolling Stones pianist Ian Stewart] went out and got some more. So, take a song like Rocks Off; the two rhythm guitars are a ’55 or ’56 Telecaster – a very good sound.”

Keith was relentless. You could tell when you had a great take but it was Keith who had to say, ‘Yeah, that’s it‘

What do you recall about the tracking the guitars on Tumbling Dice? How did those sessions go?

“The recording for Tumbling Dice went on for about two weeks. I had 40 or 50 reels of tape. Trying to get everyone in the same room at the same time in a good mood was very tough. The arrangement was being changed around a lot. It was tough to get a groove on that one and it was tried in various different formats.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I remember Keith sitting in his chair playing the refrain over and over again for two or three hours without moving. That was in the afternoon before anybody got there. He was trying to lock in the hypnotic part of the vibe. Keith was relentless. You could tell when you had a great take but it was Keith who had to say, ‘Yeah, that’s it.‘ He was sort of running the music.

“In the end we got a very good take up until the breakdown. Charlie had a bit of a mental block about the breakdown and outro section, so we did an edit section and Jimmy Miller played the ending. I suggested that we double track the drums. Charlie said, ‘Well I’ve never done that before.‘ I said, ‘Let’s just give it a shot to thicken it up.‘ So he played the double-tracked drums up until the breakdown and then Jimmy Miller doubled his drums in the end. That one went on and on and on.

“I think Rocks Off took a bit of time, too. It wasn’t so much that we’d work for 12 hours and not have anything to show for it. It was more about getting everyone in the room at the same time willing to work without any distractions.”

What tune was the easiest to record from a guitar standpoint?

“Probably All Down the Line. Happy was also pretty easy. I think we got that the first day.”

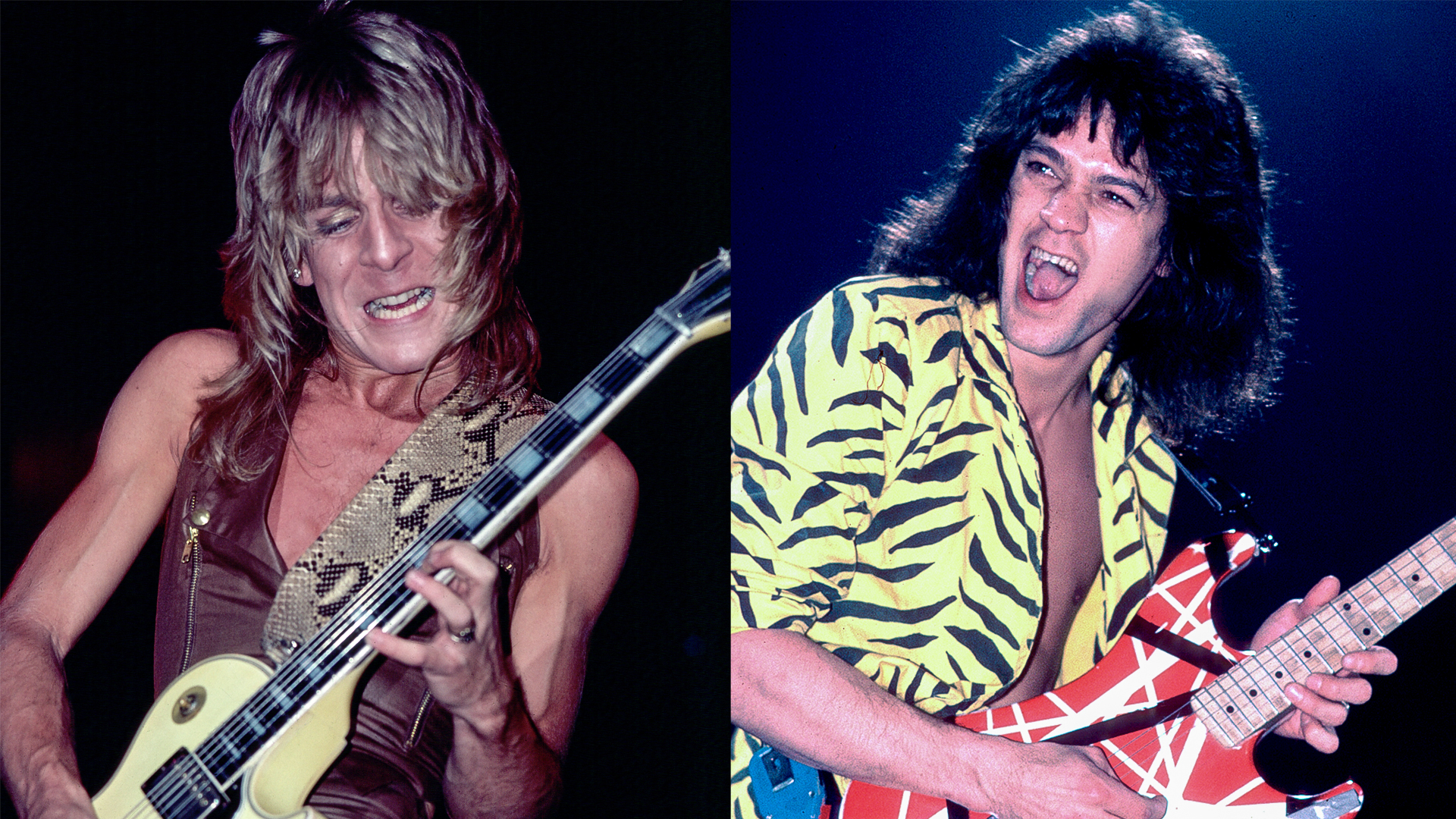

What can you say about the interplay between Mick Taylor and Keith Richards?

“Mick would play the top lines. Keith would write the songs most of the time, Mick [Jagger] would come up with the lyrics and melody, and Mick Taylor would just play around whatever they came up with. There was a little bit of tension from time to time. I remember once, Keith said, ‘You play too fucking loud. I can’t work with you in the room right now,’ which is a great line coming from Keith. That was just band politics that evening.

“The thing that astonished me about Mick Taylor is that he would come up with something different every take and it was usually just faultless. Intonation on slide can be a little tough, but he would jump two, three octaves, and the note was always spot on and his vibrato was excellent. I had a very joyous time listening to him.

“Mick had the technique of having a bottleneck on his little finger and then he would play chords with the other three fingers. He would play live on everything – he didn’t do overdubs. He would play exceptionally well on every take. And Keith, well, he came up with those magical rhythm parts that the songs were based upon.”

What was it like when they were all playing together?

“In those days you knew you weren’t going to get anything good until Keith started leaning over and looking at Charlie and then Bill got up out of his chair. They could play really shabby. Then, over the course of five minutes, it would turn from fairly shabby into magic. It was my job to capture those magic moments.”

What involvement have you had with the Exile reissues?

“I did a voice over on the DVD part of the package. I’ve done tons of interviews. But I haven’t had any musical involvement. I talked to Keith about the reissue a couple of months ago. I said, ‘Shit man, I should be doing that because I know more about it than anyone.’ I said, ‘I should send you the new Steve Miller that I’m working on, it’s Chicago blues.’ He said, ‘You send me yours and I’ll send you mine,’ and of course I sent it to him and he never sent me anything. So they didn’t let me put my hands on it, which is a drag.

“I think it has something to do with me turning Mick Jagger down years ago. I had shaken hands with Les Dudek on a Wednesday. We were in the workshop at the old Record Plant. Les asked me to do his record and I said yes and he said let’s shake on it, so we did. The next day Mick calls and asks if I want to come to Paris to do an album. I said, ‘Fuck, of course I do but I can’t. I shook hands with somebody yesterday.’

“I should have just called Les Dudek and said, ‘Listen mate, you’re going to have to wait,’ but I was trying to be honorable. And Mick said, ‘I don’t understand.’ I don’t think he’s ever forgiven me for that.”

Did you have any sense at the time that Exile would come to be regarded as such an important album?

“I knew that from my end it was the most important thing that I had ever worked on, and I had worked on Sticky Fingers, and worked with George Harrison, Paul McCartney, Jethro Tull, Free, Clapton, and, of course, Led Zeppelin. But for me this was the most important project that had come down the pike and I was fixated on it.

At that time the Beatles had broken up and the Beach Boys weren’t doing much – the Rolling Stones were the center of the bloody universe for rock and roll

“I think I knew more about what was on the tapes than anybody else because I was concentrating so hard. I knew what all the details were and that’s why in the end Mick said, ‘Here are the tapes, go mix the bloody thing. You’ve got three days. Goodbye.’ Everyone else was sick of the damn thing.

“It was as important a part of my life as anything had been. It was like going to school in a way because I learned about perseverance. I also learned that there was another way to live, beyond the norm as it were, because there was some behavior that was… I don’t know. It was all good fun.

“It was an epic production. It went on for a very long time. I’d never worked in that fashion before, living in the south of France on the Mediterranean with the Rolling Stones. And at that time you’ve got to remember that the Beatles had broken up and the Beach Boys weren’t doing much – the Rolling Stones were the center of the bloody universe for rock and roll. And rock and roll back then meant a little bit more than it does now.

“It had social significance, breaking down the establishment and all that. It represented the way a generation felt about things. It had more meaning than it does now. Now it’s just, ‘Oh I like that music, I’ll buy it or download it.’

“Back then it was almost like a bloody religion and the Stones were at the center of everything. So if you could put yourself in my shoes, you’re at the center of the universe, you’re working with the Stones in the south of France, you’re working at Keith Richards' house, you’re getting paid really well, and you’re only 21 so you have your youth, and the music is just fabulous. What is there to complain about?”