"He really lived it": Lightnin' Hopkins picked cotton and worked on a chain gang before becoming the most recorded of the postwar bluesmen – and schooling the likes of Billy Gibbons and Johnny Winter

"Lightnin' did everything the way you'd think a real blues player would do…" The story of Lightnin' Hopkins: Sage, scoundrel and natural-born storyteller

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Lightnin' Hopkins: Mojo Hands & Barrelhouse Boogies was first published in Guitar Player, October '97.

"I had the one thing you need to be a blues singer," Lightnin' used to say. "I was born with the blues." The songs he created – "barrelhouse," he called them – were as sorrowful as a cottonfield holler and as earthy as the Texas bottomlands that swallowed his sweat. "You know the blues come out of the field, baby," Lightnin' said. "That's when you bend down, pickin' that cotton, and sing, 'Oh, Lord, please help me.'"

Scars on his hands and ankles testified to stints on the chain gang and long days of driving mules and chopping cotton. But Lightnin' was indomitable, and, like Lead Belly and Muddy Waters and other great bluesmen, he played his way to better circumstances, parlaying his anger and pain into tough, deeply felt music. "The blues is a lot like church," Hopkins explained. "When a preacher's up there preachin' the Bible, he's honest to God trying to get you to understand these things. Well, singing the blues is the same thing."

Sage, scoundrel and natural-born storyteller, Sam "Lightnin'" Hopkins had a genius for improvised poetry, creating new verses or entire songs as the spirit moved him. He could sing about hairstyles, being broke, how his car was doing, goings-on in the club where he was performing, or the way things used to be. He damn near sang "Po' Sam" into an everyman of the blues.

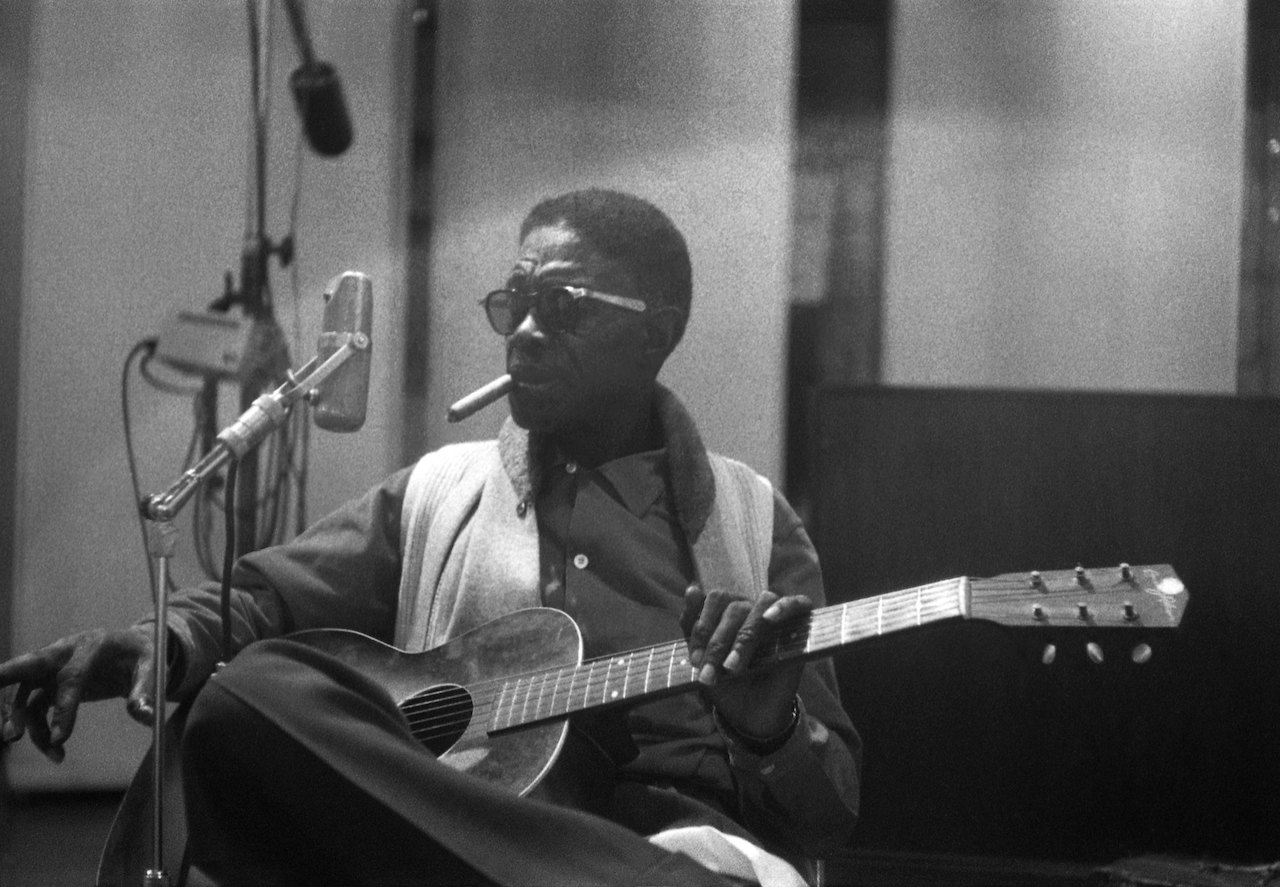

Lightnin' was a supremely confident guitarist, keeping time with his left leg while swinging hard or traveling downhome. He often played a Gibson J-50 outfitted with a DeArmond soundhole pickup, and he also performed and recorded with a small Harmony flat-top and a Fender Stratocaster. Resting his pinkie and ring finger on the face of his guitar, Lightnin' played bass and rhythm with his thumbpick while plucking solos with his bare index finger. He thrived on first-position shuffles, especially in the key of E with the fat A7 chord with the high G.

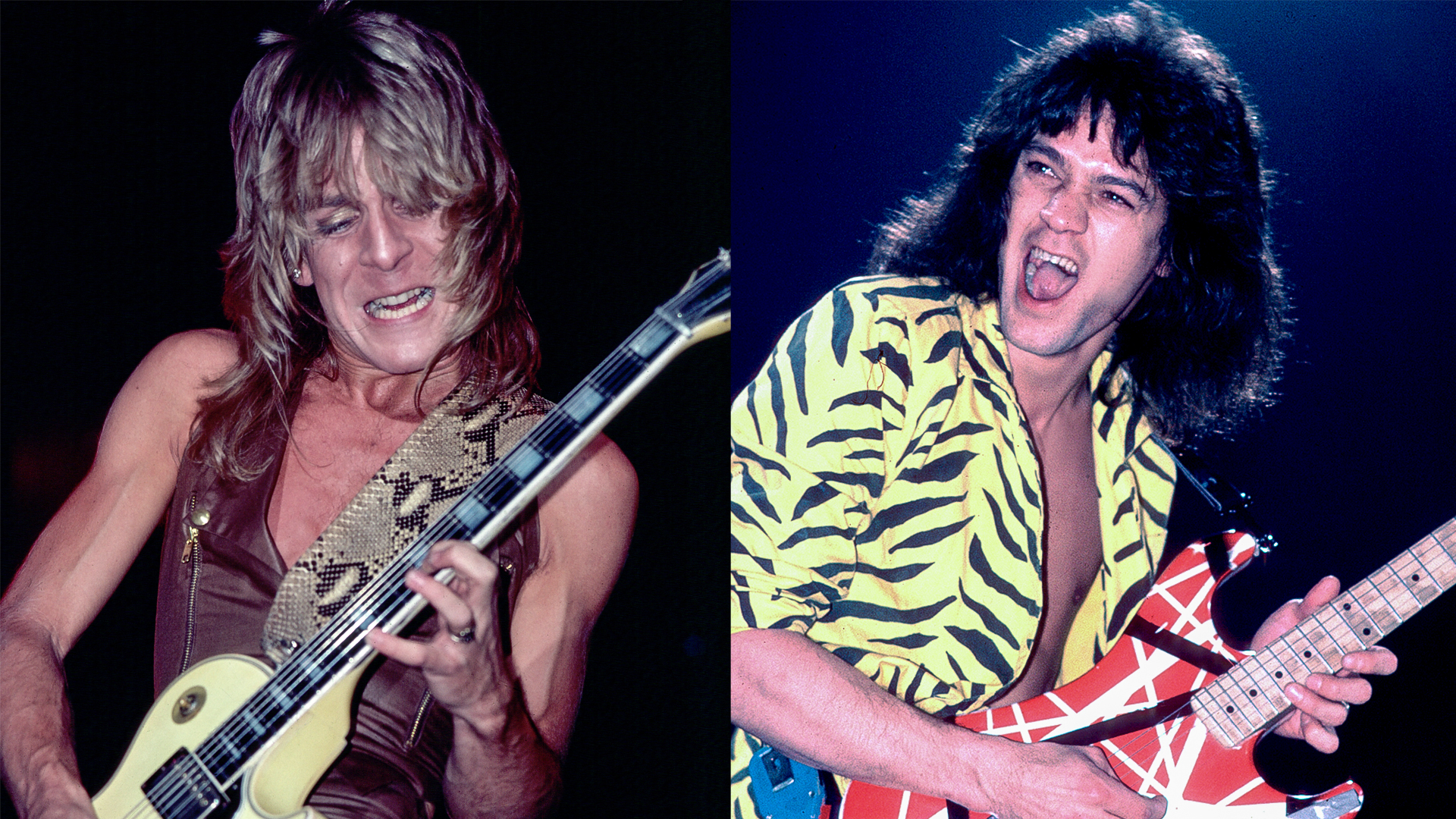

"One of the most distinctive elements of the Lightnin' sound is that turnaround in E," observes ZZ Top's Billy Gibbons. "It's a signature lick that he did in just about every song he played. He'd come down from the B chord and roll across the top three strings in the last two bars. He'd pull the pick off those strings to get kind of a staccato effect, first hitting the little open-E string and then the 3rd fret on the B string and then the 4th fret of the G string. He would then resolve on the V chord after doing this roll. It's a way to immediately identify a Lightnin' Hopkins tune."

To accompany Hopkins meant doing things his way, as Gibbons quickly learned: "We were playing a traditional blues and we all went to the second change, but Lightnin' was still in the first change. He stopped and looked at us. Our bass player said, 'Well, Lightnin', that's where the second change is supposed to be, isn't it?' Lightnin' looked back and said, 'Lightnin' change when Lightnin' want to change.' And we knew – don't do that no more!"

"You had to know and feel Lightnin' and follow him," seconds Johnny Winter. "I guess he played a lot by himself, and he didn't worry about changes. It didn't hurt a damn thing, either. Lightnin' might not change on time all the time, but he was technically a damn good guitar player when he wanted to be. He could play his butt off, and he was always his own man. A long time ago Lightnin' was playing a local bar in Houston, and one of the frats came up and said, 'Do you mind playing something by John Lee Hooker?' And he said, 'I am Lightnin' Hopkins. I don't play nothin' else.'"

Even while covering well-known songs like "Trouble in Mind" and "When the Saints Go Marching In," Lightnin' inevitably swerved the arrangement to suit himself. "When I play a guitar," he said in The Blues According to Lightnin' Hopkins, "I play from my heart and soul and I play my own, own music."

Hopkins was born in the heart of East Texas Piney Woods country on March 15, 1912. "My family, we come up in Leona County," he told Sam Charters during a 1964 Prestige session. "It's just a little old country where they farm and raise cotton and corn and peas and peanuts, things like that. So that's where I grew up to know myself -- back out from Centerville about 12 miles back in the country." Hopkins's grandfather was a slave who hung himself. His father, a hard-drinking gambler who'd done time for murder, was slain in an argument when Lightnin' was three. Sam's older brother John Henry fled the area soon afterward, leaving his mother on her own to raise Alice, Joel, A.B. and Sam.

Before he was big enough to work in the fields, Hopkins was drawn to music. "I heard my brother playing a guitar," he told Charters. "It was the first one I ever seen. He wouldn't let me play his guitar. I wanted to play it, so at last one day they come in and caught me with the guitar 'cause I couldn't hang it back up – see, I had to get in a chair to get it down. So he caught me fair. He said, 'Boy, I done told you – don't fool with that guitar.' He says, 'Can you play this guitar?' I say, 'Yeah, I can play it some.' He said, 'Well, go ahead and let's see what you can do.' I went ahead and played him a little tune, and he liked it. So he said, 'Yeah, he can play some. Where you learn that from?' I said, 'Well, I just learned it.'

"So I went ahead and made me a guitar. I got me a cigar box, I cut me a round hole in the middle of it, take me a little piece of plank, nailed it onto that cigar box, and I got me some screen wire and I made me a bridge back there and raised it up high enough that it would sound inside that little box, and I got me a tune out of it. I kept my tune, and I played from then on. So I got me a guitar of my own when I got to be eight years old."

Sam toted his guitar to a Baptist church social in nearby Buffalo, where Blind Lemon Jefferson had him hoisted to the hood of a truck so they could perform together. "Boy," the great bluesman predicted, "you keep that up, you gonna be a good guitar player." Albert Holly, an old blues player who came around to court his mama, inspired Hopkins to sing. Sam played leads alongside his brothers and sister in the Hopkins Band and gathered with them around the organ to sing "them good old Christian songs."

During his teens Hopkins played with a fiddler, serenading and passing the hat. "When I got good, I went to find the places where they'd barrelhouse at," Hopkins said. "I didn't know – I just had to wander up on them places around Jewitt, Buffalo, Crockett. They had little old joints for Saturday nights, you know." In 1927 Hopkins began playing dances and jukes around the area with his cousin, blues singer Texas Alexander, who'd just done his first session with Lonnie Johnson on guitar.

By day Sam worked the fields, chopping cotton and driving a mule. "It was hard times," he told Charters. "I was trying to take care of my wife, me and my mother. Six bits a day -- and that was top price. I swear, I would come in in the evening, and it looked like I'd be so weak till my knees be cluckin' like a wagon wheel, man. I'd go to bed, and I'd say, 'Baby, I just can't continue like that.' Look like no sooner than I go to bed and I'm ready to go catch that mule again."

The hard-drinking Hopkins got into fights that landed him on the chain gang. "I had to calm down. Man, that ball and chain ain't no good for no man. From the '20s up until the '30s I was doing that. Getting cooped up and whomped around pretty good. Somehow or another, I'd always be lucky and managed to get out." He rode the rails and stayed in hobo camps: "I had some hard days travelin', but after I stopped in places and they found out I played that guitar like I do, they'd warm me up, feed me, and make me a big sack of food and tell me I can make it."

Sam visited Houston for the first time in 1934 to broadcast with Texas Alexander and then returned home. Mance Lipscomb recalled seeing him playing an electric guitar in Galveston in '38. Sam finally moved to Houston for good and began playing on buses and in the dives along Dowling Street. Word of his performances reached Lola Anne Cullum, a talent scout who bought him his first amp and arranged his November 1946 debut session for Aladdin.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Accompanying the 35-year-old bluesman on the drive to Los Angeles was pianist Wilson Smith. "When I gets in that studio," Hopkins recounted to Charters, "they said, 'Mr. Hopkins, we wanna see what you got to offer.' I walks up there and I grabbed that old guitar, and I ran back. I sang 'The Rocky Mountain, darlin', they way out in the West.' He said, 'He's sold,' right then and there. I didn't have to hit another note. Alright. I come on down. Smith was next. He said, 'Well, let's see what y'all got to offer on piano.' I gets up there and I play the same song -- 'The Rocky Mountain' -- with Smith, and it sold him! [Laughed.] And boy, we tore the joint up. And so they named me Lightnin' and named him Thunder."

With its fearless bass licks and gripping solos, Hopkins's countrified style was fully evident on his first release, "Katie Mae Blues" backed with "That Mean Old Twister." The 78 became a hit and brought Lightnin' better-paying gigs around Houston. His second Aladdin session, held in L.A. nine months later, yielded another hit, "Short Haired Woman." Jumping from label to label, Hopkins recorded prolifically in Houston during the next eight years, taping nearly 200 selections that would eventually come out on Aladdin/Imperial, Gold Star, Modern, RPM, Jax/Sittin in With, United, Kent, Crown, Verve, Dart, Time, Mercury, Mainstream, Blues Classics, Decca, Herald, Arhoolie and many other labels.

"Lightnin' liked to make records," says producer Chris Strachwitz, "and no wonder, when he could sit down a few minutes, make up a number and collect $100 in cash. And local recording producer Bill Quinn had Lightnin' doing just that. Whenever Lightnin' needed some money he would go over to Telephone Road and walk into the Gold Star studios to 'make' some numbers. And he had a fantastic talent to come up with an endless supply of these 'numbers.' Many were based on traditional tunes he had heard in the past, but all of the songs received his personal treatment and they came out as very personal poetry." Some songs presaged rock and roll, while others were as lonesome and sorrowful as Blind Lemon's old 78s. Hopkins's biggest Gold Star singles, "Unsuccessful Blues" and "Tim Moore's Farm," crackled over R&B radio and were spun on jukeboxes all along the Texas Gulf Coast.

Besides stripped-down guitar blues, Lightnin' recorded piano and organ solos -- his "Zolo Go" was early Zydeco -- as well as tap-dancing numbers. Bassist Donald Cooks and a variety of drummers accompanied Hopkins on records between '52 and mid '54, when Lightnin' played his last major session for Herald. Shifts in R&B; and the advent of rock and roll caused a lull in demand for middle-aged blues artists like Hopkins and Muddy Waters. Lightnin' produced only three singles during '55 and '56 and didn't record at all in '57 and '58. Then came a dramatic turnaround: Educated white people became interested in folk blues.

On January 16, 1959, Hopkins recorded his first album, for Folkways. Sam Charters, who'd written about Lightnin' in his monumental book The Country Blues, produced the session and provided the gin. "We recorded it in the shabby room he was renting," Charters wrote, "and I held the microphone in my hand so I could move it down toward the guitar when he was playing a solo, and then move it close enough to his lips for his singing." Lightnin' paid homage to Blind Lemon with "Reminiscences of Blind Lemon" and covers of "Penitentiary Blues" and "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean." Subsequent 1959 sessions with Mack McCormack captured a wealth of improvised blues and traditional songs.

Chris Strachwitz made a pilgrimage to visit Lightnin' at a Houston tavern in 1959. "The songs I heard him sing were incredible improvised poetry, made up on the spot about whatever was on his mind that day or night," Chris observed. "Rhymed and underscored by the piercing sound of the amplified guitar droning over an ancient humming amplifier, Lightnin' sang about how he hardly got to the beer joint that night because it had been raining all day and his car hit all the chuckholes on the road since the water covered them all.

"He moaned about his arthritis bothering him on a humid night like that. He yelled out at several women jiving in front of him and pointed his long fingers at them while he told them a piece of his mind, always rhymed to the slow beat of his guitar and Spider, the drummer, who bashed out a powerful sanctified beat. Lightnin' hardly seemed to end one number – it was a continuous rap with his audience." The performance inspired Strachwitz to form Arhoolie Records, which has several top-drawer Hopkins albums in its catalog.

Lightnin', Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee and Big Joe Williams converged in a Los Angeles studio to record together for World Pacific in July 1960. In October, Hopkins joined Joan Baez and Pete Seeger onstage at Carnegie Hall to record "Oh Mary Don't You Weep." During the next two-and-a-half weeks, Hopkins recorded nearly four dozen songs at various New York facilities, including two Bluesville albums, a Candid LP and the Fire release of "Mojo Hand," a compelling piece of voodoo imagery that became his signature song.

An instant hit on college campuses, Lightnin' crossed over to jazz audiences, being voted Best New Star -- Male Vocalist in the 1962 Down Beat critics poll. Lightnin' explained his performance strategy to Charters: "See, here's the way I play songs. I goes on. If my first song don't hit 'em, my second one will, because I bring a feeling. And if they don't get the first feeling, they get the second feeling, and I got 'em and gone! Because I rocks the joint that way."

Lightnin' recorded prolifically during the '60s, with standouts on Arhoolie, Bluesville, Prestige and Verve. He joined his brothers Joel and long-lost John Henry in Waxahachie, Texas, for a particularly memorable Arhoolie outing in '64.

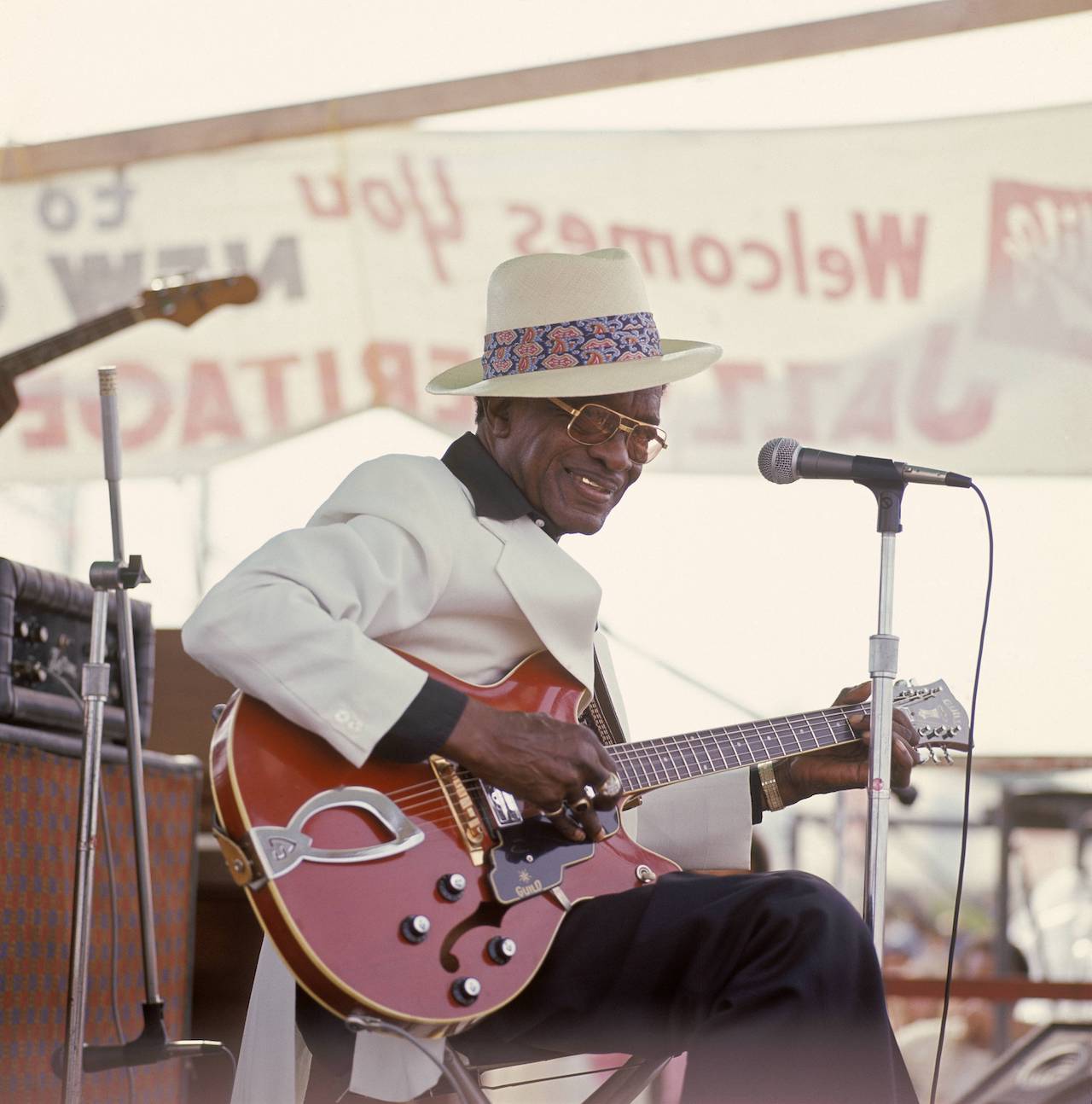

Unlike his Lone Star contemporaries T-Bone Walker, Gatemouth Brown and Lowell Fulson, Lightnin' did not want to promote himself by touring. He had an aversion to airplanes, refused to own a phone, and was known to refuse a $2,000-a-week tour to stay home and play in a dingy club for $17 a night. With his shades and shiny Cadillac, Lightnin' was a respected man about town who loved drinking, fishing, going to rodeos, shooting craps and playing pitty pat. Most of all, he remained true to who he was –"a country boy moved to town."

"I always thought Lightnin' Hopkins was a real cool guy," says Johnny Winter, "because he could do big shows and then go out and play on the corner or on a bus or in a little juke joint. It didn't seem to bother him a bit. He could go from acoustic guitar to electric guitar or from playing by himself to playing with a band. Lightnin' was a real blues guy."

By the end of his life Lightnin' Hopkins was likely the most recorded of the postwar bluesmen. He exerted an enormous influence on other musicians – Albert, B.B. and Freddie King, Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy, J.B. Lenoir, Otis Rush, Albert Collins, Son Thomas, R.L. Burnside and Jimi Hendrix all praised his records.

On January 30, 1982, Po' Lightnin' died of cancer of the esophagus in Houston's St. Joseph Hospital. "Lightnin' was one of the last of a dying breed," said Johnny Winter just after the funeral. "There are always going to be blues musicians, but it's just different with people who really lived the whole thing in the country and could talk about chopping cotton and pulling corn and riding freights. Lightnin' did everything the way you'd think a real blues player would do. He took care of the people he loved, and success never really seemed to go to his head. He did exactly what he wanted to do, and he sure gave us a lot of good blues."

Jas Obrecht was a staff editor for Guitar Player, 1978-1998. The author of several books, he runs the Talking Guitar YouTube channel and online magazine at jasobrecht.substack.com.