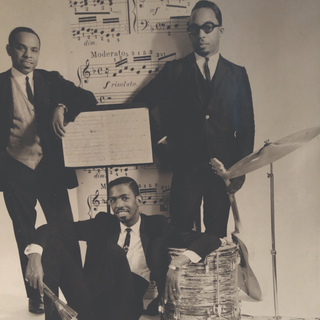

"Bird just grinned. He’d never heard a guitar played like that!" He saw T-Bone Walker, worked with Charlie Parker and uses a drawer-knob instead of a pick: Chicago jazz supremo George Freeman, 96, looks back over an epic career

He’s a bebop originator who’s played with everyone from Charlie Parker to Jimmy McGriff and who saw the popular music transform from jazz to swing and beyond. Now in his 90s, George Freeman has a new album out…

George Freeman May have only been in his teens, but he was a visionary. In the early 1940s, as a youngster in the band program at DuSable High School, Chicago’s legendary birthplace of bebop, Freeman shared classes with jazz legends attending the school, who over the years included saxophonists Gene Ammons, Eddie Harris, Johnny Griffin and his own brother, tenor saxophonist Earle “Von” Freeman.

But while other guitarists were settling for the more established role of a chord-strumming accompanist, Freeman saw another place for guitar, in the front, where he could play the same lines as these great Chicago tenor players.

Fast forward a few years to his live 1950 performances with Charlie Parker at the Pershing Ballroom. Recordings from these dates show Freeman didn’t shy away from using amp overdrive and even power chords as he swapped solos with Bird, firing off chromatic phrases and his trademark escalating chord clusters, which race away from the key until he brings everything home and right back into the groove.

As rock and rhythm and blues began to take over the market from jazz in the 1950s and ’60s, Freeman absorbed these signs of the times by teaming up with jazz organists like Jimmy McGriff and Charlie Earland to champion a blend of hard-boppin’ soul jazz with references to Chicago gospel and blues.

In the ’70s, Freeman’s creative fires turned white hot on Gene Ammons’ 1971 album The Black Cat!, the 1972 solo disc Franticdiagnosis and McGriff’s live album from the same year, Concert: Friday the 13th – Cook County Jail.

In addition to his bebop virtuosity, Freeman is a lyrical melody player with a deep blues feel and appreciation for space, as showcased on tracks like “Confirmed Truth,” from his 1974 solo effort New Improved Funk.

Now 96 years old, George Freeman has been part of every stylistic development of modern jazz guitar and made groundbreaking contributions to the instrument. Over an 80-year career, during which he has recorded and performed as a sideman, bandleader and composer, he has loyally kept Chicago as his home base, aside from a brief aborted excursion to New York City.

Together with his nephew, the highly active tenor saxophonist Chico Freeman, he continues to be an integral part of the Windy City’s soulful groove-and blues-driven brand of jazz.

In June, Freeman released The Good Life (HighNote Records), a collection of original compositions and covers that find him supported by bassist Christian McBride, drummers Carl Allen and Lewis Nash, and the late Hammond organist Joey DeFrancesco.

At this stage of his life, Freeman’s playing has become more lyrical and economical, but equally masterful. We spoke to him just a few weeks before his performance at the 2023 Chicago Jazz Festival.

Bird just grinned from ear to ear because he’d never heard a guitar played like that!

George Freeman

On The Good Life, which was tracked at Chicago Recording Company, you’re leading two trios: one with Christian McBride on bass and Carl Allen on drums, and the other with Louis Nash on drums and the late Joey DeFrancesco on organ. How did you meet the musicians, and how did you select the songs?

I’ve been around so long, and the record company wanted me to get more recognized than I had been, so they put me together with these bigger names. But surprisingly enough, these musicians had known about me and my previous albums, like Franticdiagnosis.

Playing with them also enabled me to record what I wanted to record: no rock and roll or rhythm and blues, just straight-out jazz. I picked the compositions quickly and we recorded them quickly, because we didn’t have much time. But that goes to show when you’re working with people of that caliber. They were there to support me, and they gave me all the respect you could ask for.

Who inspired you as a guitarist?

I saw T-Bone Walker, and while he didn’t inspire me, he was exciting, and people were going crazy for him. Who inspired me was my family. My brothers Bruz [drummer Eldridge “Bruz” Freeman] and Von, and my parents. They taught me how to approach the guitar. When I started, the guitar wasn’t as famous as it is now. It was a good instrument, but it wasn’t the one that inspired me. That was the saxophone. When I was coming up, you had Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins and all those people.

You studied at DuSable High School, which Dinah Washington, Gene Ammons and Von also attended. What was the jazz scene like in Chicago when you came up?

When I was 13 to 15 years old, I was playing football or basketball and somebody told me that there was another guitar player living across the street from me who was really good. He taught me how to approach the guitar by playing scales and chromatics. He and Von taught me how to play standards. We’d play standards day and night.

Von also used to put on records with tenor players and say, “Listen to what he’s saying.” And I’d ask. “Well, what is he saying?” After first thinking he was playing the same thing over and over again, I learned that the player actually was telling a beautiful story.

I’ve been a jazz man all my life, and used to listen to jazz as a kid. My dad was a policeman, and he used to put his Majestic radio on and we’d listen to all the jazz giants of that time. [Majestic was manufactured by the Grigsby-Grunow Company of Chicago from 1927 to 1955, and trademarked as “The Mighty Monarchs of the Air”.] My mother was into gospel, and I’d listen to her sing. And I’d listen to Von play the saxophone.

Once I began to hear the story, that was it for me, and I haven’t been the same since. When Charlie Parker got out there, it just blew my mind. And Dizzy Gillespie was there too. Bebop came in. You’ve got to remember that during that time, they were all telling their story, but they were swinging the story. And all the kids got into bebop and the words [the musicians’ slang expressions]. That’s how powerful it was.

Now I know about bebop, but you have to find your own style of playing it and the direction you want to take. That’s the complicated part. But that’s what I did.

Bebop is harmonically advanced music. How did you learn to play it?

My brother and I were learning by mostly playing standards. Beautiful songs, like “Stardust.” You had to learn the chord changes for all of them, and the more standards you learned, the more you could play. But you can’t leave out that I was coming up in the swing era, so everybody was swingin’, playing standards and playing blues.

But my brother taught me about telling the story, and the story was not in the blues. I mean, the blues was in there, but he wanted me to “hear” standards. And when I heard Charlie Parker play standards, he took me for a ride.

During those formative years, you learned to play the solos of other musicians, like Lester Young’s “D.B. Blues.” Some think transcribing is a great way of building vocabulary, while others disagree. What are your thoughts on that?

You’ve got to remember that I had a band that played standards during the swing era, and the kids in the audience could dance to swing and sing the horn players’ solos. Then Lester Young got here, and I had learned his solo on “D.B. Blues” because it was popular with the kids. When I played it for them, they loved it. But when I played it in front of Lester, he didn’t appreciate it too much.

I also played with Coleman Hawkins, and I’ll never forget when he looked at me onstage and told me, “Blow!” My life has been very successful as far as playing with good musicians.

You had just turned 20 in 1947 when you moved to New York City to perform and record. What was that experience like for you?

When I went, my hopes were very high. Johnny Griffin and his band took me there. The first other musician I met there was Sonny Rollins. I was ready, because I was already playing bebop in Chicago. I got turned around, and came back home. It’s a sad story. But I met all the great cats, including John Coltrane, when they were young just like me.

When you came back to Chicago, you met Charlie Parker. How did that happen?

My brother Bruz was working with Sarah Vaughan, and she had a manager who knew Charlie Parker [‘Bird’]. Since Bird was coming to Chicago, she asked Bruz if there was anything about the city he wanted to tell him, and he mentioned that I was here. When Bird got here, he contacted us.

There’s an audio recording of the two of you playing “Keen and Peachy” live at the Pershing Ballroom in 1950. What was your collaboration like?

When you get onstage, you try to play something that everybody knows. Bird had a heart of gold, and he could play anything. I had been playing standards and dances, no problem. But when he called out that song, I got nervous. I was standing next to him playing, and he just grinned from ear to ear, because he had never heard a guitar player play like that.

You did two onstage collaborations: one in Chicago and one in Detroit. Did you ever talk about recording?

Bird asked me. He asked me to come to New York City. And those were the last words he spoke to me. I never did go, because I was working with my brothers.

Going outside the harmony is a big part of your playing. How did you get into that?

I heard Coltrane go outside in his playing, while my brother was playing inside, and I don’t think anybody went outside the way Coltrane did back then. That goes for all the cats like Sonny Stitt, Dexter Gordon and Gene Ammons. They didn’t go out. So when I joined Gene Ammons’ band [in 1969], I used to go outside on purpose, and he loved it.

In a Downbeat interview with Ammons from 1970, he said that he didn’t like avant garde playing, but he liked how you did it because you were still connecting with the rhythm section.

You can’t just go out and stay out there. You’ve got to have the melody in your mind and also know when to come back in again with the drummer and the organ player. I used to make Gene Ammons dance.

When you came up in Chicago, were the jazz and blues scenes very separated at that time?

I don’t think anything is ever separated from the blues. It’s always been prominent. Charlie Parker was instrumental in the direction blues was taking as far as horn players was concerned. But players like B.B. King had nothing to do with that.

Since you were so influenced by horn players, how did the guitar end up being your instrument?

Well, I like the sound of the guitar. My brother tried to teach me how to play the alto saxophone, but my lips weren’t strong enough, so that didn’t last. When I got to DuSable High School, the musical director there asked me what instrument I wanted to play. I said “I want to play the guitar.” He looked really surprised, as he thought I was going to pick anything else but guitar.

Your solo on “Franticdiagnosis” is an amazing bop showcase, where you’re not afraid of switching to a more biting pickup sound and getting some amp dirt as you end it all in an escalating frenzy.

That solo just happened. I was young and fast. The musicians who entered my mind at the time were Charlie Parker and John Coltrane. Nowadays, players have such a hard time with the swing.

What advice would you give to players to help them with swing?

Swing is about supporting, and you’ve got to support. You’ve got to love your fellow musicians. When they take a solo, you’ve got to listen, push them and make them feel good. You want to make them sound good. That’s the secret. And I expect the same from my musicians when I’m soloing. If you don’t support me, you don’t have any love in your heart for me.

Players can get so focused on what they’re doing. Musicians back then had a way of approaching and connecting with other musicians. I was never inspired by Miles Davis, but I did admire him for always keeping a swinging rhythm section.

For the last few years, you’ve been playing with a very unorthodox guitar pick: a dresser drawer knob. What motivated you to go with that kind of pick?

It took years to come up with this. The rounded edge has enabled me to slide over the strings and go up and down the strings like a maniac. I used to use stiff picks and big, fat silver dollars, but then I couldn’t play fast. When you get to be my age, you’ve got to find some way to make things work.

By George: The bebop style of George Freeman in 5 tracks

These five tracks capture highlights from Freeman’s 80-year career as a bandleader, sideman and composer. His career has included collaborations with Charlie Parker, Christian McBride, and also many of the finest jazz organists including Jimmy McGriff and Joey DeFrancesco.

Franticdiagnosis: George Freeman (Franticdiagnosis, 1972)

You think you’re listening to uptempo swing until Freeman switches pickups and starts tearing through melodic and harmonic boundaries. Upcoming jazz masters like Christian McBride took notice.

The Black Cat: Gene Ammons (The Black Cat! 1971)

With fiercely grooving support from Ammons, Ron Carter, Harold Mabern and Idris Muhammad, Freeman brings his solo from a hip, funky simmer to a rapid, escalating boil. He also wrote this composition.

Keen and Peachy: Charlie Parker (The Complete Live Performances on Savoy)

Recorded live at the Pershing Hotel Ballroom in 1950, on this track Freeman proves that he’s a worthy soloist alongside Bird during a time when bebop guitar was extremely rare.

Freedom Suite, Pt. 1: Jimmy McGriff (Concert Friday The 13th Cook County Jail, 1972)

In this live performance before inmates at a Chicago jail, Freeman digs deep into blues and doesn’t fear to let a few moments of silence go by between his phrases. Freeman takes the first guitar solo. The twangy solo that comes later is likely performed by O’Donel Levy.

Up and Down: George Freeman (The Good Life, 2023)

Recorded back when Freeman was 95, the joyful musical camaraderie between him, organist Joey DeFrancesco and drummer Lewis Nash is unmistakable in this bopping jump tune. Although Freeman’s playing has mellowed and become more lyrical, his tone is as beautiful as his time is solid. DeFrancesco passed away shortly after this album was recorded.

George Freeman's new album The Good Life is available to buy and stream

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“If we were recording at Olympic Studios, we would often hear Led Zeppelin. I’d see Jimmy Page sitting there, overdubbing in darkness”: Peter Frampton reveals the stories behind five of his classic tracks

“Noel’s process is purely guitar. He’s so in love with the chords, and he was cycling through and through... He wouldn’t stop until he was satisfied”: How Noel Gallagher and Beck helped bring the Black Keys' latest funky full-length, Ohio Players, to life

Most Popular