"I wouldn’t normally be caught dead with one because I think they’re ugly. But that’s the only guitar I used." Mikael Åkerfeldt talks about his surprising choice of guitar for Opeth's latest album

From a ‘90s Telecaster to Hank William’s 1940s Martin D-18, it’s been an interesting year of gear for the Swedish guitarist

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For the past 13 years, Opeth have ignored their death metal roots in favor of a vintage prog sound inspired heavily by the likes of King Crimson and Jethro Tull.

Although the group returns to a heavier vibe on its latest release, The Last Will & Testament, guitarist Mikael Åkerfeldt chose to go without his signature PRS guitars this time out. As he explains in a revealing new interview with Total Guitar, only one guitar was fit for the job: a 1990s Telecaster with a humbucker in the neck and a single-coil in the bridge.

Apparently, he isn't a fan of the guitar — at least not its looks.

“No one’s seen me with a Tele before,” he confesses. “I wouldn’t normally be caught dead with one because I think they’re fucking ugly! But that’s the only guitar I used."

And why is that?

"It doesn’t hum when you raise the gain,” Åkerfeldt explains.

That seems reason enough for the guitar to be among his favorites. After all, the Tele was featured across Åkerfeldt's score for the Swedish Netflix series Clark, which tells the tale of the origins of Stockholm Syndrome. His familiarity with and trust in the instrument meant he didn't take another guitar to the studio when it came time to track Opeth's latest.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I love the feel of that Tele," he offers. "It’s so comfortable that I didn’t feel the need to bring anything else. I also knew if it didn’t work, Fredrik [Åkesson, co-guitarist] would have a bunch of shit for me to try.”

He adds that a time-ravaged ‘60s Marshall cabinet, which he believes has “probably never been serviced,” also proved a vital ingredient for the record.

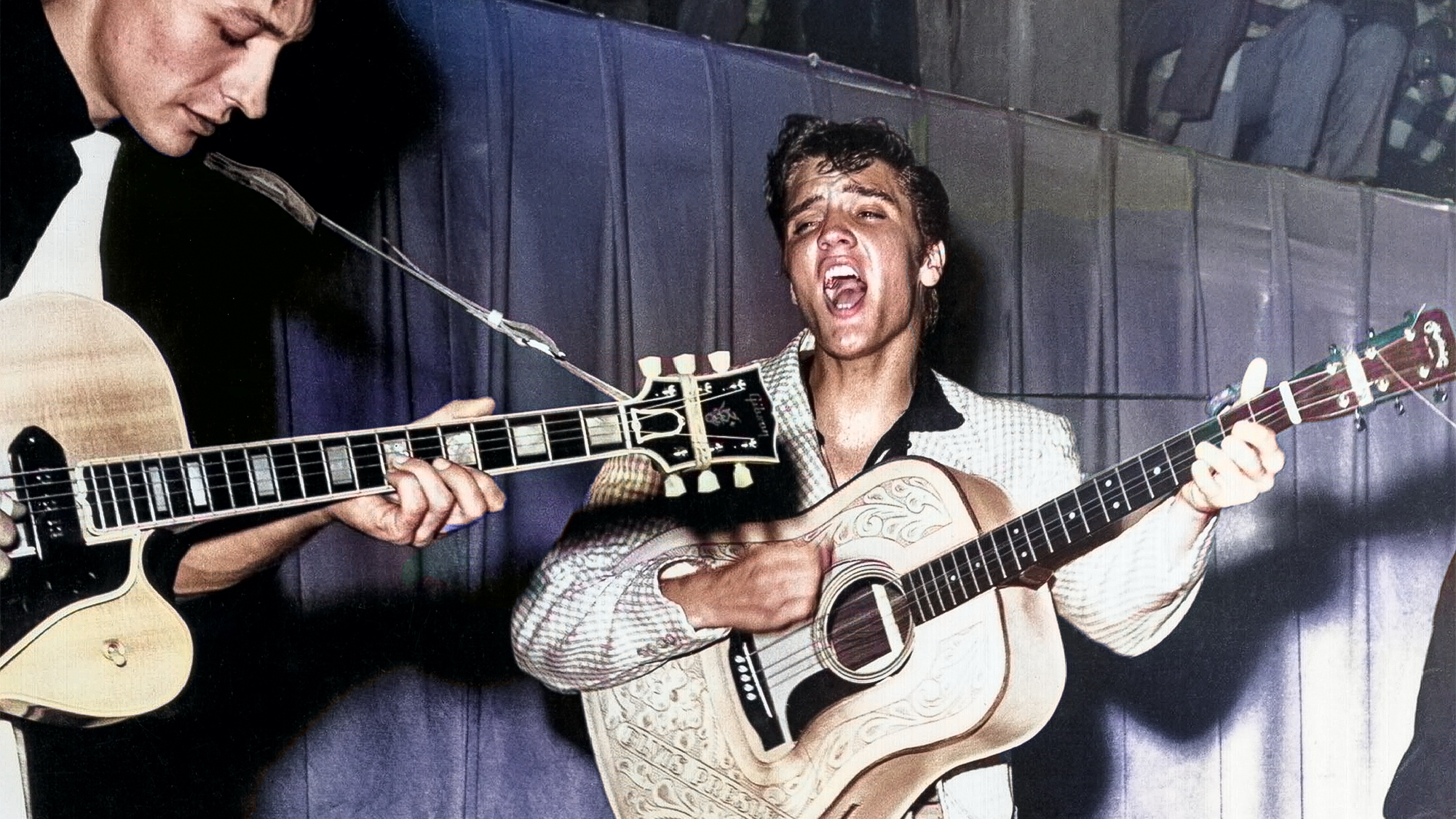

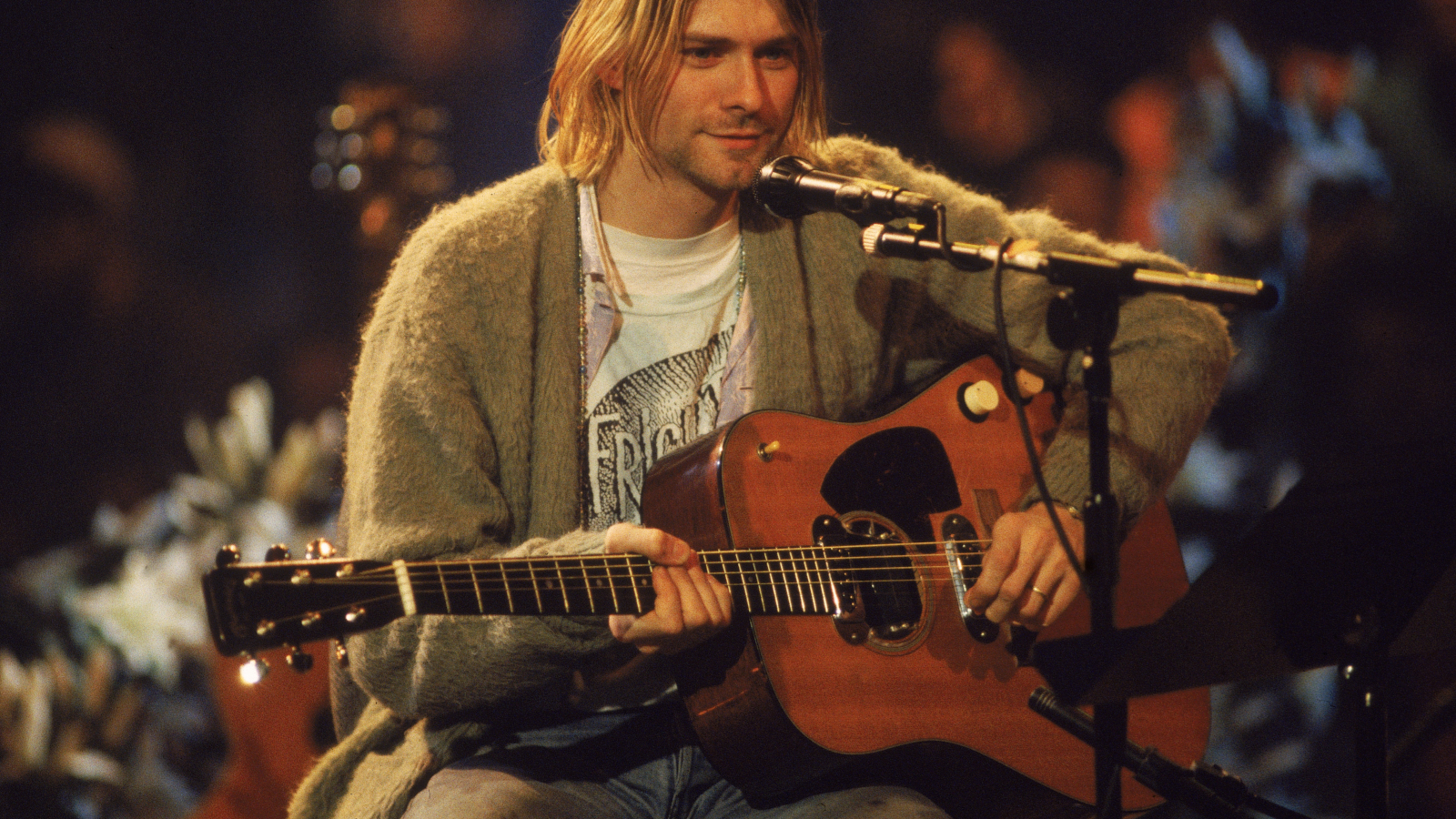

Meanwhile, Opeth paid a visit to the Martin Guitars factory in Nazareth, Pennsylvania during their U.S. tour. While there, Åkerfeldt and Åkesson played a trio historic acoustic guitars: Kurt Cobain’s “beat up” D-18, a Martin formerly belonging to Johnny Cash (complete with a dollar bill stuck between the strings) and Hank William’s 1940s D-18. Åkerfeldt called fingerpicking on the latter a “scary” experience considering its age, history and frailty.

Opeth’s new album marks the first time they’ve had a well-known guest feature, with Åkerfeldt’s idol, Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson contributing spoken word and a flute solo.

“I originally only asked for the spoken word, then an email comes in like, 'Do you need some flute?'” he told Prog Magazine. “At the time I didn't have a part, but I wasn't going to say no! And of course, in comes this fucking amazing solo. I've cried to Jethro Tull. They've given me so much joy over the years, it's incredible.”

In fact, Åkerfeldt’s Telecaster experience shares parallels with Anderson, who played a Les Paul for the first and only time when recording "Locomotive Breath." Alone in the studio, he took it upon himself to fix a song that wasn’t working, grabbing Martin Barre’s trusted six-string to lay down the song’s rhythm parts.

A freelance writer with a penchant for music that gets weird, Phil is a regular contributor to Prog, Guitar World, and Total Guitar magazines and is especially keen on shining a light on unknown artists. Outside of the journalism realm, you can find him writing angular riffs in progressive metal band, Prognosis, in which he slings an 8-string Strandberg Boden Original, churning that low string through a variety of tunings. He's also a published author and is currently penning his debut novel which chucks fantasy, mythology and humanity into a great big melting pot.