“Eventually, you get to the take where it all comes together and it's like a firework going off.” Recording engineer Glyn Johns on why he never used click tracks when working with the Rolling Stones, Beatles and Led Zeppelin

He’s recorded and mixed seminal records by some of rock’s biggest artists, and click tracks were always left out in the cold

Esteemed recording engineer Glyn Johns, who has worked with some of the world's biggest bands, has reflected on how modern recording methods differ from the 1960s, arguing that many today stray from what makes an album truly special.

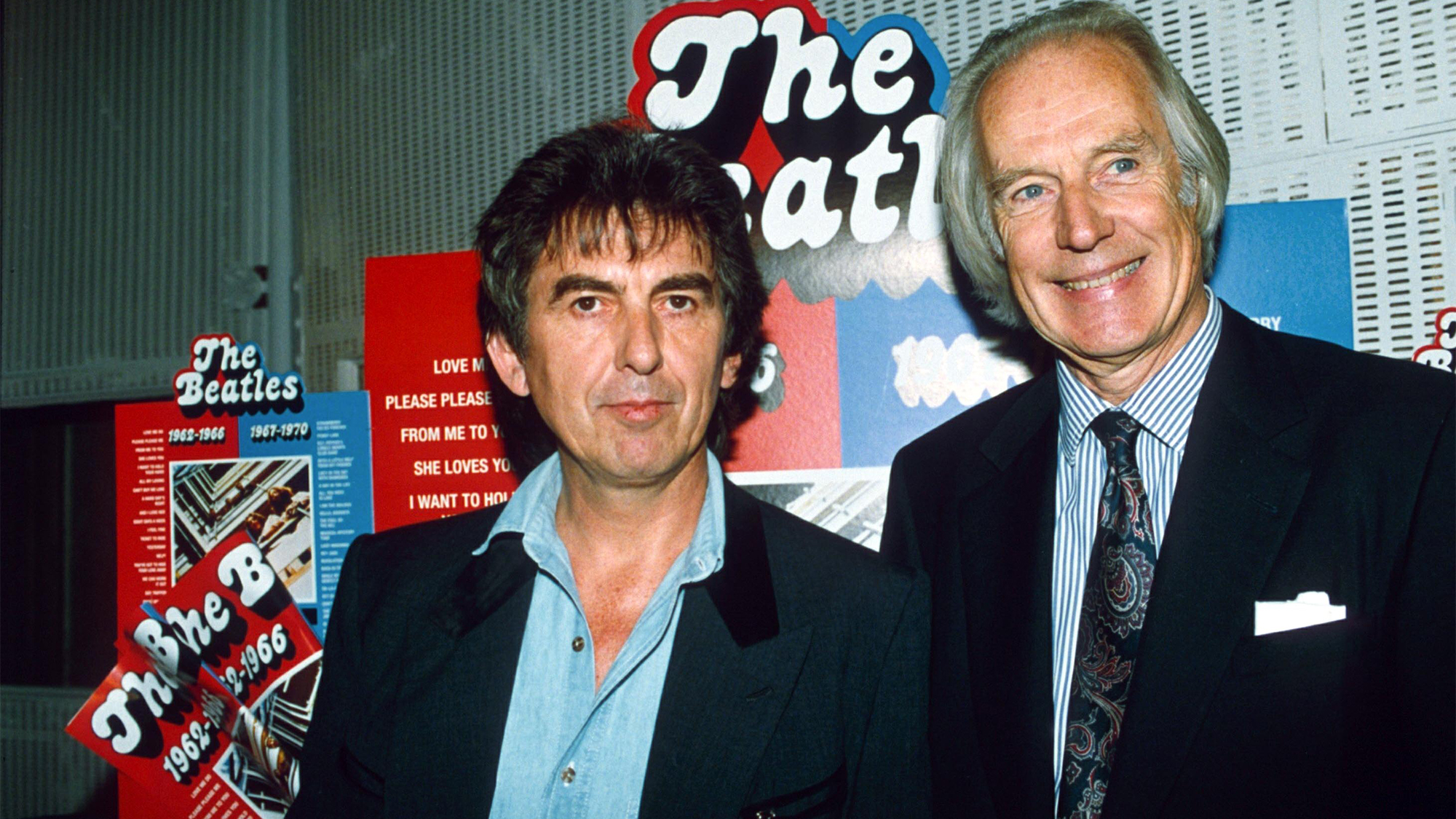

Johns, whose resume includes working on classic records with the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, and many others , is the latest guest to feature on Rick Beato’s YouTube channel. During their sprawling, hour-long chat, Johns, who got his first production credit working with skiffle singer Lonnie Donegan in the late '50s, has rallied against a part of the recording process rarely overlooked by contemporary producers.

During the 1960s and '70s, Johns worked extensively with the Rolling Stones, engineering and mixing records such as Their Satanic Majesties Request, Beggar's Banquet and Let It Bleed. He also worked on early tracks recorded for the Beatles' Abbey Road and all of Let It Be, as well as Led Zeppelin I. Johns had further credits with Eric Clapton, Humble Pie, and the Who, including their 1971 album, Who's Next. Through it all, he never used click tracks and recorded the band with as few overdubs as possible.

When asked by Rick Beato the inevitable question of whether he used click tracks, the engineer utters the word “no” five times in quick succession.

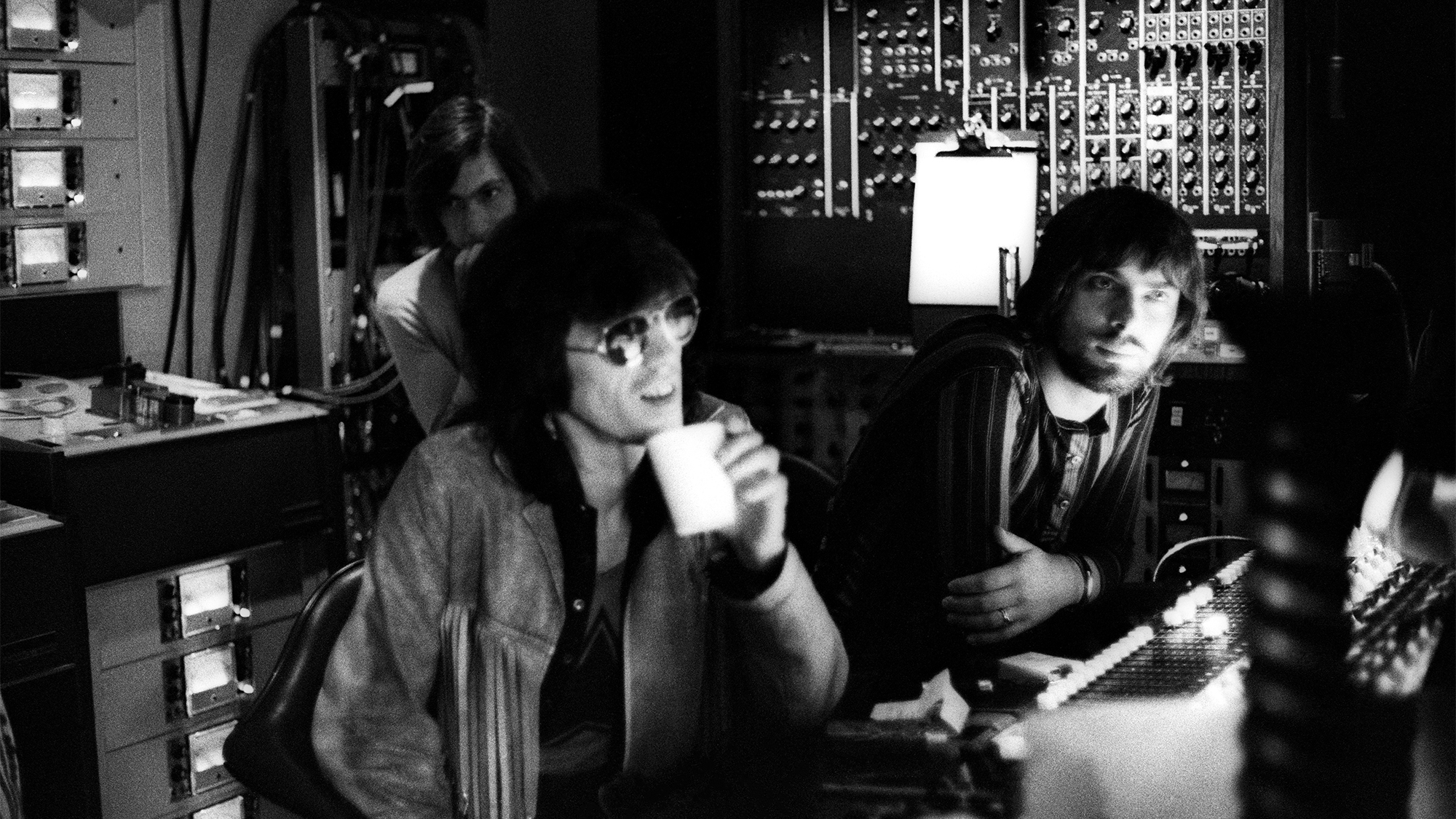

“Against my religion,” he states. “This is entirely different from nowadays, [where] everything has to be controlled. My job was about capturing a performance of a group of people and their subliminal interactions with each other.

“I completely disagree with clicks, particularly for rock and roll,” he adds. “It has to breathe.”

That said, there was at least one exception. When Pete Townshend brought in his song "Baba O'Riley" for Who's Next, the group was forced to play along to the pre-recorded organ track — performed on Townshend's Lowrey Berkshire Deluxe TBO-1 organ using the "Marimba Repeat" setting — which is heard at the start and throughout the track. (Johns incorrectly recalls the song as the Who's 1965 hit "My Generation.") To his surprise, the usually erratic Moon was able to play along perfectly.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“It was the first time I'd ever played in something for a band to play to, which would be the equivalent of a click,” he explains. “Pete Townshend had already done the synthesizer track, which had a rhythm to it. So they had to play to that, and the one person I thought would never be able to play along was Keith Moon, because he was a loony. But he was perfect. Every single take.”

Johns feels just as strongly about the need for musicians to play together, rather to work piecemeal through overdubbing. In the 1960s and early '70s, overdubs were typically added to an initial group performance, such as when Eric Clapton’s performed his lead and solo guitar work on the Beatles' “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” It would be used as well to improve live recordings, such as when Kiss overdubbed much of the instruments and vocals on Alive! (for which Ace Frehley and Paul Stanley used some of Peter Frampton’s gear).

But with the the arrival of 16- and 24-track recording in the 1970s, many acts began laying down entire songs one instrument at a time. Johns says this was never his style.

“My principle has always been that everybody should play at once,” he insists. “That way, you'll get a performance of a piece of music rather than some sterile, perfect nonsense. Music is about emotion, for God's sake. And emotion is expressed by a group of people playing together.

“You could do six takes and they'd all be different,” he says. “Eventually, you get to the take where it all literally comes together and it's like a bloody firework going off. The difference is extraordinary. And that came about through people subliminally interacting.

“They're not even aware of it. They're probably concentrating. However, they're being tremendously influenced by what everyone else is doing,” Johns continues. “Equally, everyone else is being influenced by what they're doing. And if you overdub something, you're influenced by what precedes you; what you're being played, but you're clearly not influencing what happened before.”

A freelance writer with a penchant for music that gets weird, Phil is a regular contributor to Prog, Guitar World, and Total Guitar magazines and is especially keen on shining a light on unknown artists. Outside of the journalism realm, you can find him writing angular riffs in progressive metal band, Prognosis, in which he slings an 8-string Strandberg Boden Original, churning that low string through a variety of tunings. He's also a published author and is currently penning his debut novel which chucks fantasy, mythology and humanity into a great big melting pot.