Take Your Improvising and Chord Melody Arrangement to the Next Level With the Teachings of Musical Genius Vic Juris

These amazing techniques and tips from the master mentor are guaranteed to up your jazz game

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On the morning of New Year’s Eve 2019, I and many others bid a sad farewell to the exceptionally talented and creative musical genius Victor E. Jurusz, Jr., better known in the overlapping worlds of jazz and guitar as Vic Juris.

Vic’s impact as a player and improviser was felt deeply by all who were fortunate enough to experience and be inspired by his artistry. Legendary jazz guitarists such as Larry Coryell, Jimmy Bruno, Frank Vignola and Bireli Lagrene, all of whom performed and recorded with Vic, sung his praises.

Throughout his professional career, Vic collaborated onstage and in the studio with many notable bandleaders, including Phil Woods, Mel Torme, Lee Konitz, Barry Miles and Richie Cole. But he is best known for his 23-year tenure working with legendary saxophonist Dave Liebman, a partnership that generated a collection of invigorating music through recordings and documented performances that will be listened to and dissected for many years to come.

Vic was also very prolific as a recording artist in his own right, having released more than 20 albums with the Steeplechase and Muse record labels, among others.

The deepest harmony and hippest single-note lines effortlessly flowed out of Vic. Whether you strove to be the next Pat Metheny, wanted to better your approaches to improvising and chord melody arrangements, or had no interest in jazz at all, after listening to Vic you would suddenly want to learn how to play like him. As fate would have it, Vic was also a gifted teacher and dedicated mentor. Along with many aspiring guitarists over the past few decades, I was very fortunate to have studied privately with him.

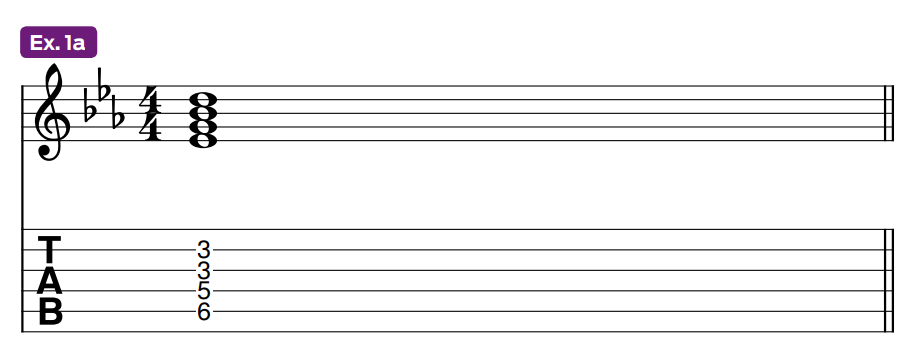

Vic always reminded me that, as a guitar player in an ensemble, my job was 25 percent soloing and 75 percent comping. To bolster my vocabulary of chord voicings, he would engage in what he called “chord discovery,” whereby he would show me how to enhance stock voicings. For example, take the close-voiced Ebmaj7 chord in Ex. 1a.

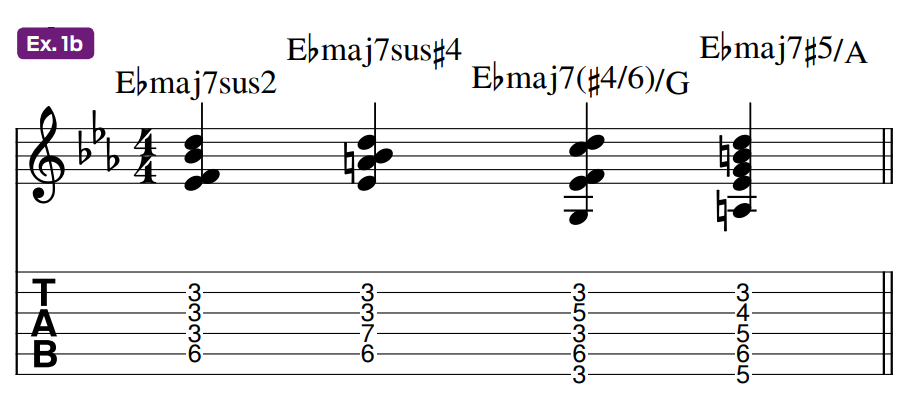

Vic would morph this common chord into modern-sounding alternatives, like those shown in Ex. 1b.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Considering the Ebmaj7sus#4, Ebmaj7(#4/6)/G and Ebmaj7#5/A, which all contain a #4 (A), you get a glimpse into Vic’s affinity for Lydian- and Lydian-#5-based textures. To finger the Ebmaj7#5/A shape, hook your fret-hand thumb over the top side of the neck to fret the low A note on the 6th string.

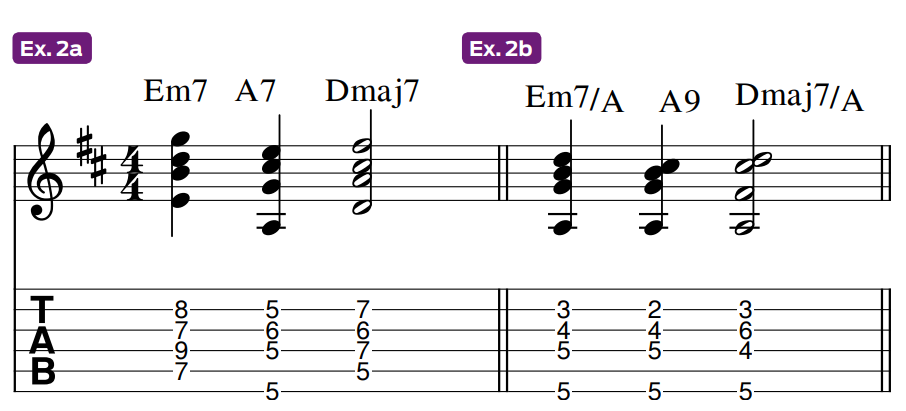

The Lydian mode wasn’t Vic’s only cache for fresh and exotic sounds. Take Ex. 2a, where we start with a basic ii - V - I progression in D major (Em7 - A7 - Dmaj7), played with standard tetrads (four-note chords).

One of Vic’s staple approaches was to leave the root-note movement to the bass player and voice the progression with a common bass note, in this case A, which he would employ as a pedal point, or pedal tone, as shown in Ex. 2b. This created a more modern sound and provided tighter voice leading from chord to chord.

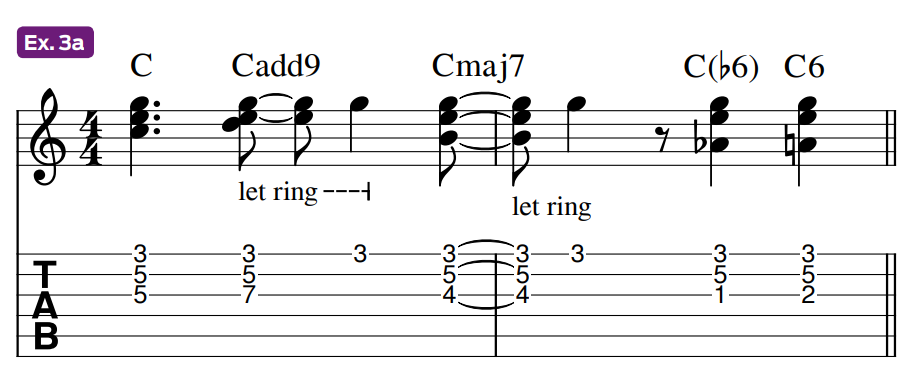

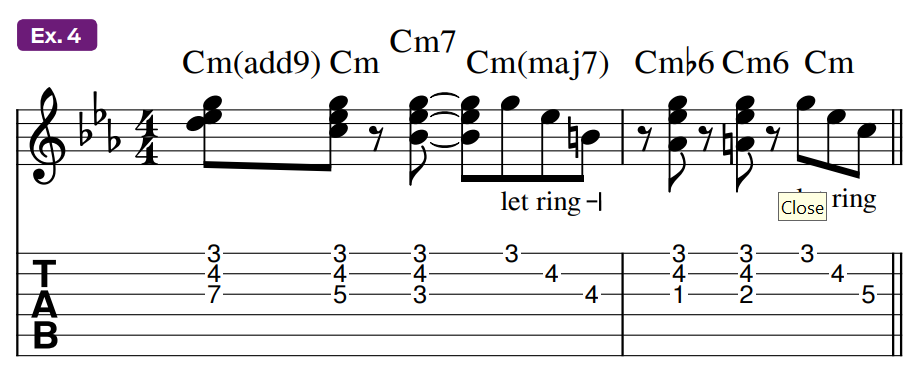

Another of his signature voice-leading moves was to add “extensions” to close-voiced triads by lowering or raising one note, as demonstrated with C major (C, E, G) and C minor (C, Eb, G) triads in Examples 3 and 4, respectively.

To create movement, Vic used an idea he called “movable roots on triads” and both examples employ the following chord tones in the lowest voice: 9, 7, b7 (minor only), 6 and #5. The idea was to “orchestrate” your voice leading as if you were writing for a string or horn section.

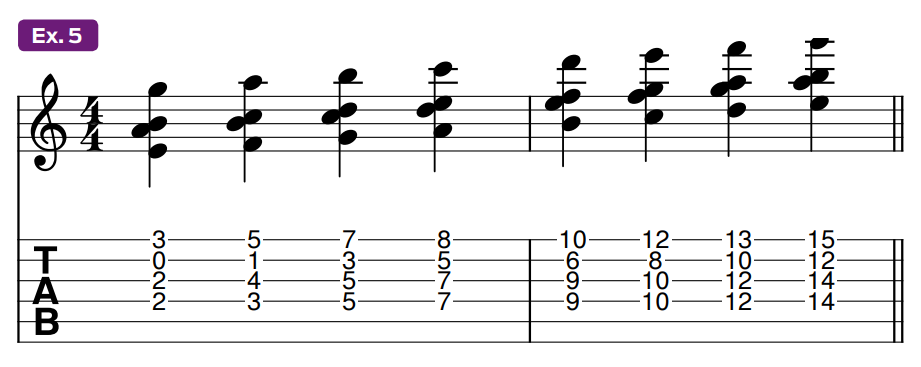

Unhappy with conventional methods, Vic developed his own harmonic components that he conceptualized as “intervallic structures.” Combining intervals to create nameless four-note chord structures, he organized them into modal chord scales.

Ex. 5 parades a sequence of ascending structures comprised of stacked 4th and 6th intervals based on the C major scale (C, D, E, F, G, A, B), with each successive four-note structure moving up one scale tone on each string.

Notice the wide fret-hand stretches required here, which are technically challenging to make, so ease into them.

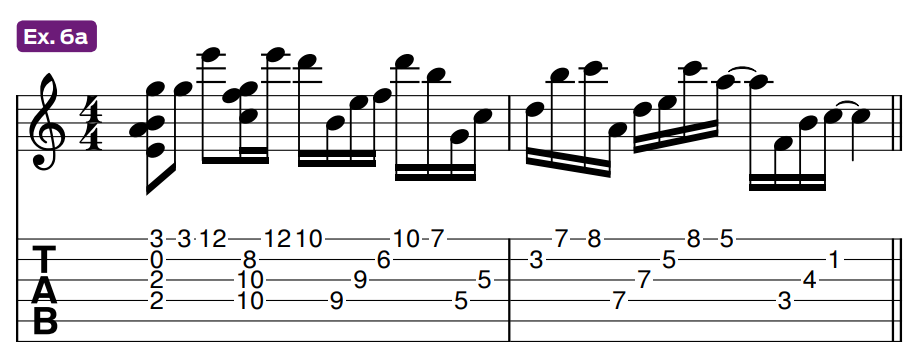

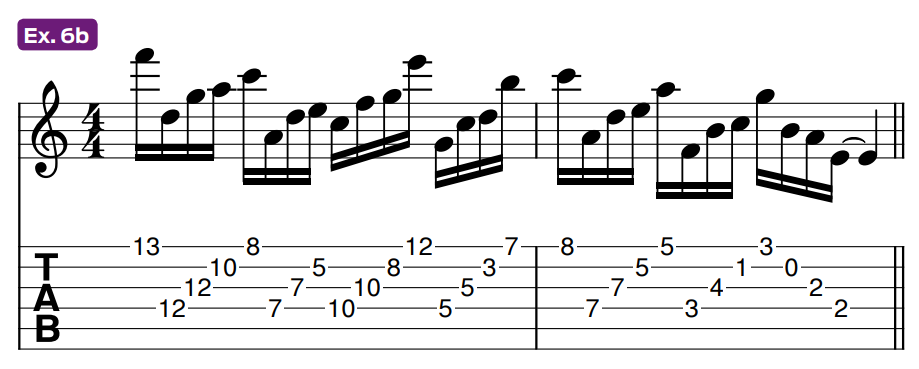

Examples 6a and 6b apply the voicings from this sequence in a more musically interesting manner, which was something Vic encouraged his students to try and do with any new concept as soon as possible.

In this case, we’re arpeggiating the shapes and letting the notes of each four-note group ring together.

The goal of these structures was to create a flexible harmonic device that can be applied to modal comping situations. This same chord scale works well for standard tunes like “So What” and “All Blues,” which happen to be in the relative modes of D Dorian (D, E, F, G, A, B, C) and G Mixolydian (G, A, B, C, D, E, F), respectively.

When it came to soloing, Vic was a master melodic improviser, and he had an insightful approach to guiding students. An infamous Vic homework assignment was to compose a continuous, unbroken eighth-note line over one complete chorus of a tune. With his ninja-level sight-reading skills, Vic would play your chart flawlessly and then proceed to go over the good, the bad and the ugly. Depending on where you needed help, he would compose lines for you to play, analyze and try to include in your next attempt.

Vic would write out two-bar ii - V lines with a felt pen, an act only to be attempted by a seasoned pro. The ideas of tension and release and half-step melodic resolution to a tonic chord were starting points.

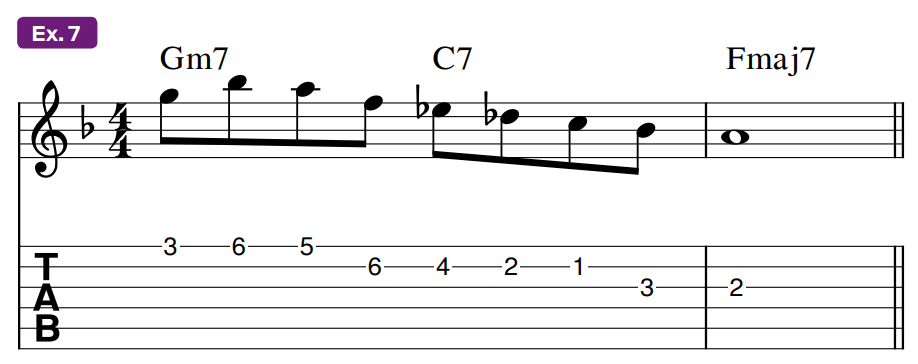

Ex. 7 is an example of a line he would ink without hesitation. The goods were in the #9 (Eb) and b9 (Db) played over the C7 chord during beat 3 of bar 1, as well as a Bb (the b7 of C7) on the upbeat of beat 4, descending a half step to A (the 3 of Fmaj7) in bar 2.

Vic would turn me onto lines reminiscent of that shown in Ex. 8, wherein a 16th-note double-time feel is introduced over a ii - V line in the key of Eb. Looking closer, I discovered the melodic minor scale – spelled intervallically 1, 2, b3, 4, 5, 6, 7 – was an enticing option to play over the ii chord (in this case, F melodic minor: F, G, Ab, Bb, C, D, E), despite the theoretical clash between its natural 7, E, and the chord’s b7, Eb, along with reinforcing tensions over the V7 chord, Bb7, namely the #9 (C#), b9 (B, or Cb) and #5 (F#), which all live in the B melodic minor scale (B, C#, D, E, F#, G#, A#).

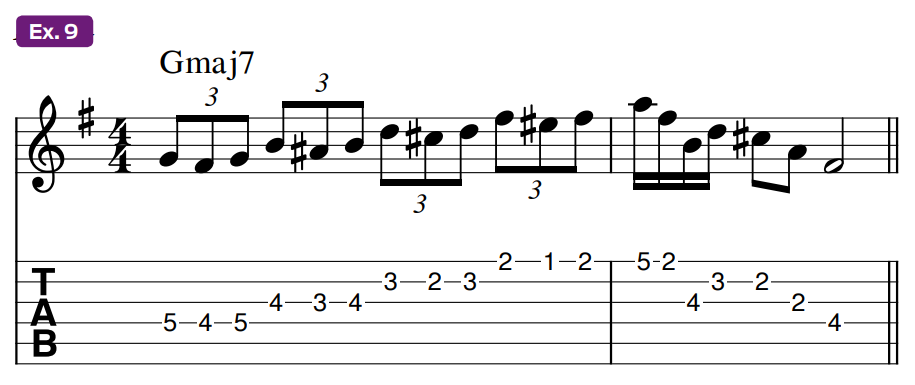

Other cool line-construction concepts Vic taught me were what he called “side slipping” and “line compression,” which he would demonstrate over a single chord. In Ex. 9, the bebop-style idea of side slipping is demonstrated in bar 1, via an ascending Gmaj7 arpeggio (G, B, D, F#), for which each chord tone is melodically embellished with its chromatic lower neighbor, a half step below.

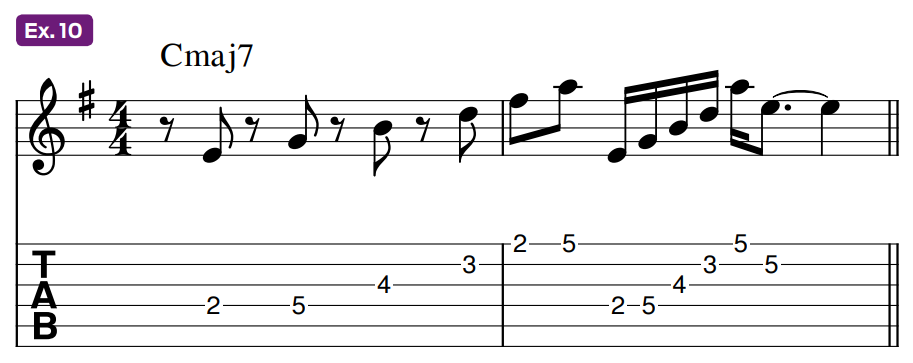

Line compression is revealed in Ex. 10, wherein an Em7 arpeggio (E, G, B, D) is superimposed over a Cmaj7 chord in bar 1 with a syncopated eighth-note rhythm, then repeated and compressed into successive 16th notes beginning on beat 2 of bar 2.

Once again, Vic’s favorite mode, Lydian, is in play in both of the previous examples, courtesy of the C# (the #4 of G) on the downbeat of beat 2 of bar 2 in Ex. 9, and the F# (#4 in C) on the downbeat of bar 2 in Ex. 10.

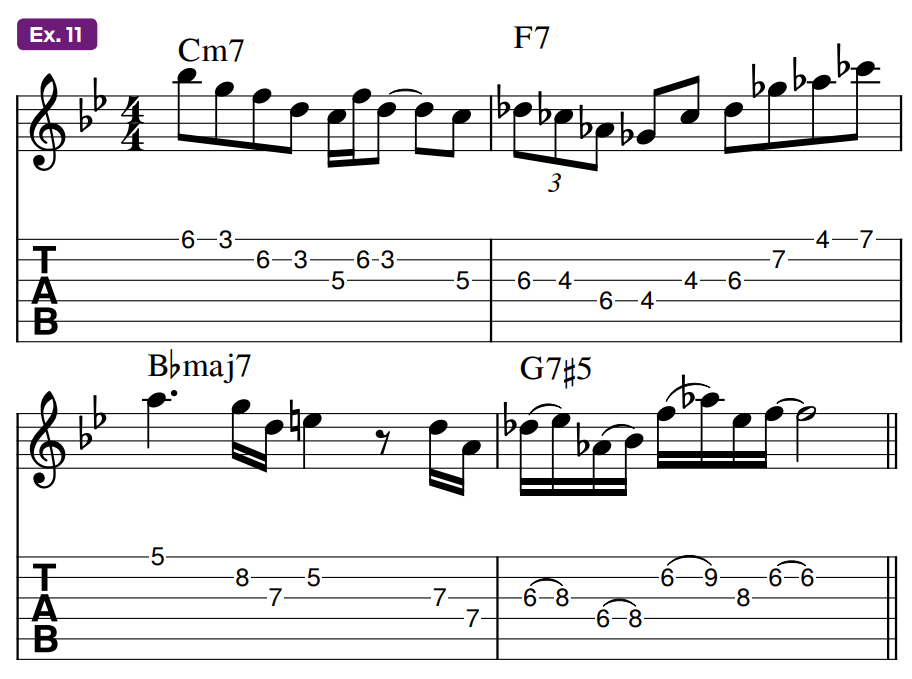

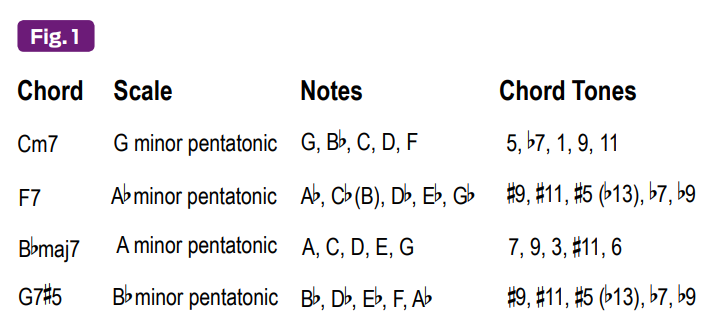

As one progressed with line development, Vic presented more advanced ideas, such as superimposing chromatically ascending minor pentatonic scales over a ii - V - I - VI progression, as shown in Ex. 11 in the key of Bb.

The table in Fig. 1 outlines the scale tones played against the chords and the resulting chord-tone colors and tensions.

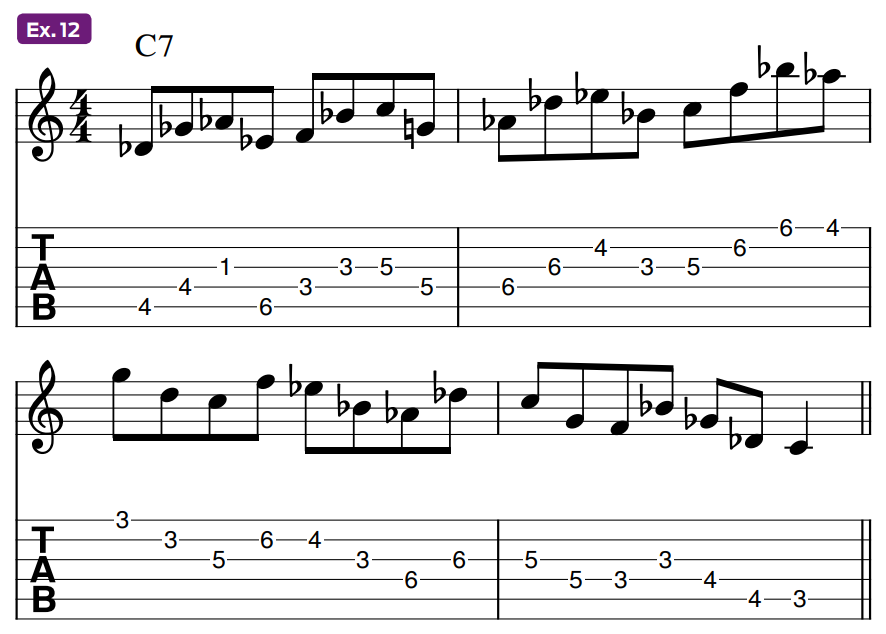

Vic also shared his fascinating signature quartal-based line ideas. Ex. 12 is a four-bar phrase wherein perfect 4th intervals are cleverly arranged to weave inside and outside the confines of C7. A closer look reveals one of Vic’s most important concepts, something he called “line shapes.”

At the core of his soloing was an intention to organize lines into four-note groups that follow numeric patterns of direction.

Notice how the first two bars in Ex. 12 have four-note sequences following a “three-up, one-down” pattern, while the last two bars flip it to “three-down, one-up.”

I had to make use of this pattern in my streaming eighth-note assignments, along with other variables of one and three notes, as well as two and two.

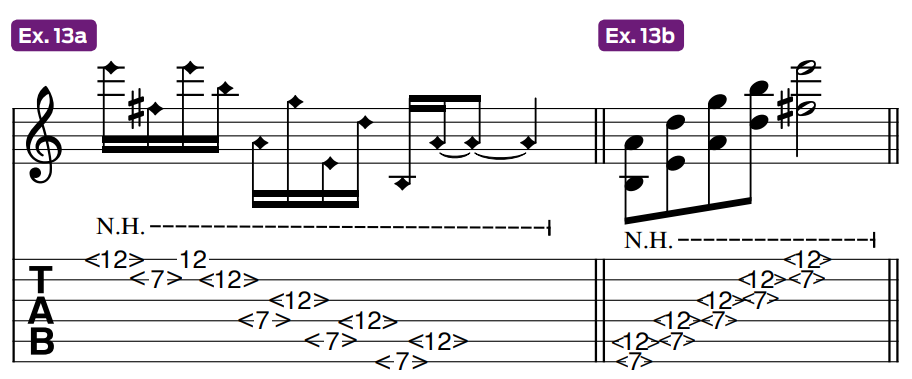

If you asked Vic about something outside his methodology, he was always happy to give you the gold. One of my favorites was his use of harmonics. His command of the technique and its applications was mesmerizing, as recalled in Examples 13a and 13b, wherein natural harmonics (N.H.) are employed to create cascades of chime-like tones.

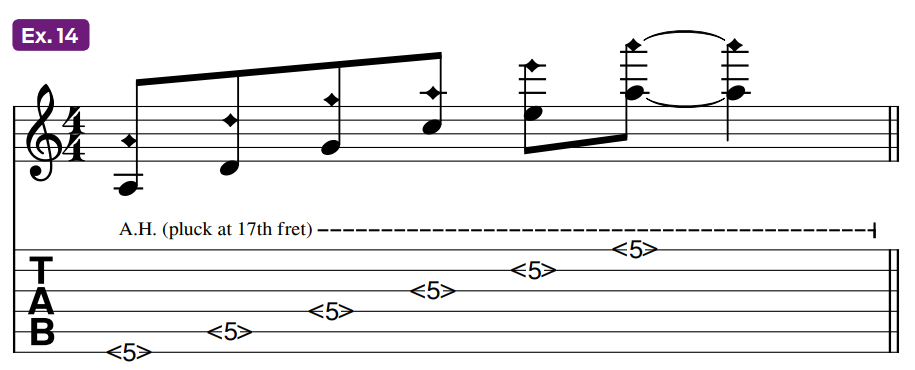

Vic would also perform artificial harmonics (A.H.) with fretted notes, using a technique whereby he would momentarily clasp the pick between his thumb and middle finger, allowing him to use the tip of his index finger to lightly touch a string exactly 12 frets above a fretted note while picking it.

For instance, in Ex. 14, notes barred at the 5th fret serve as fundamental tones for octave-higher harmonics sounded by successively picking the strings in ascending order while lightly touching them directly above the 17th fret with the tip of the pick-hand’s index finger.

Taking that approach to the next level was the more advanced “harp harmonics” technique passed down to Vic from its pioneer, Lenny Breau, via Larry Coryell.

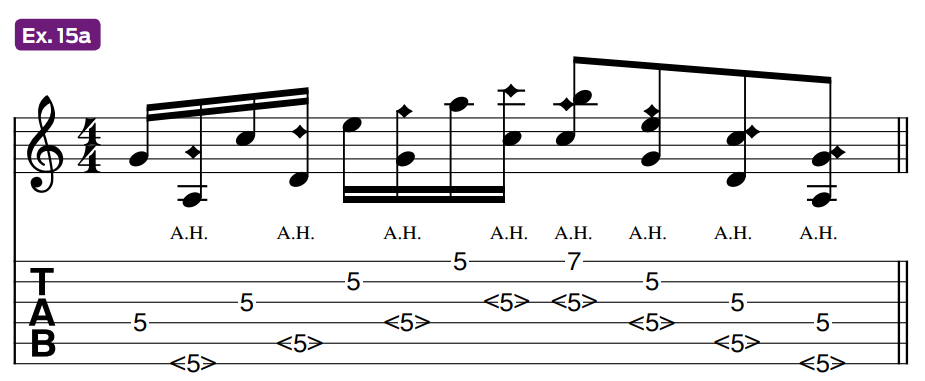

It entails holding a chord shape with the fret hand and using the artificial-harmonics technique detailed above in alternation with regular, non-harmonic notes, picked with the 3rd finger, and letting everything ring together, as shown in Ex. 15a.

Done correctly, this creates a dreamy, harp-like effect. Notice how harmonics and non-harmonics are played together on the descent. The result is a tantalizing interval of a 2nd heard between the non-harmonic on the higher string and the harmonic on the lower string.

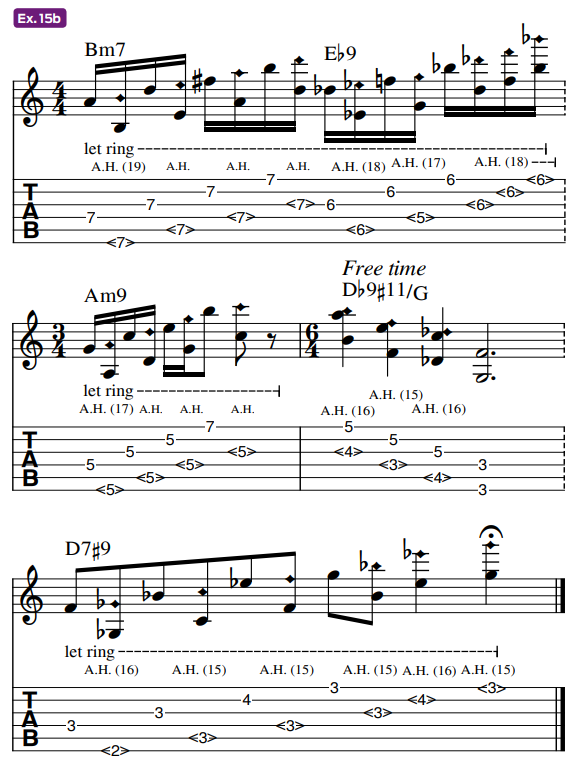

At the end of a tune, Vic would gracefully apply this tactic over enchanting changes with laser accuracy and a rubato feel, much like what you have in Ex. 15b.

Vic Juris did so much for the music he loved and for the people around him. He was a musical guide and mentor as well as a life coach. If you were Vic’s student, you loved him not only for the music that seemed to effortlessly flow from him but also because of what he was about. He nurtured you not only as a musician and guitarist but also as a person.

Humble to the core, Vic gave you everything he had seen and learned. I will continually give thanks to him by striving to do the same.

Chris Buono is a top-selling TrueFire Artist with nearly 50 instructional videos, and a featured instructor on guitarinstructor.com. Bookending his years as a Berklee professor, he authored eight books, including the popular Guitarist’s Guide to Music Reading and his most recent publication, How to Play Outside Guitar Licks.