The Raising of Lazarus: Bringing an Old Gibson Back From the Dead

The old Gibson was unrecognizable and unplayable. But detective work uncovered the tale behind its demise, and inspired its new owner to resurrect it.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A year has passed since since my friend and fellow aging regional rock guitarist John Dougherty called me out of the blue and asked when I might be coming up his way, to Collinsville, Oklahoma.

I said I had no plans but could come up if he needed me. He then explained that he had a guitar he wanted to give me. I was, to say the least, surprised, and asked if we could meet the next morning at the local mom-and-pop diner on Main Street around 11:30. He said that would be fine, and we hung up.

En route to my appointment, I was fearful of what exactly he might give me. I’d known him to be an avid collector of fine guitars ever since his career as a drug representative had sent him all over the state to visit physicians. On those trips, John would hit every pawnshop and music store within his itinerary.

Not only was it ugly and smelly but neither he nor I could determine what model Gibson it was

I thought of the old adage about not looking a gift horse in the mouth and proceeded to meet him at the appointed time and location. When he entered, he did not have the instrument with him. He explained it might be too “loud” for the establishment.

When I followed him out to the trunk of his car, I found out loud meant smelly. He proceeded to remove plastic bags concealing the ugliest 1950s brown Gibson case I had ever seen.

I grew more apprehensive. When he opened the case, there appeared a most hideous and pitiful old guitar. Not only was it ugly and smelly but neither he nor I could determine what model Gibson it was. He did have the wiring and pickups to go with the guitar. They included two P-90s of early manufacture, a single tone control and two volume controls.

I stared at the gift. “I don’t know whether to say ‘Thank you’ or ‘Screw you,’” I remarked after a moment. We both chuckled. John explained that he had purchased the instrument about 20 years prior in McAlester, Oklahoma, at middle, and what was left of one strap pin had nearly rusted away.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

There were three major cracks in the top, along with roughly 12 tiny drilled holes that I could not account for, as well as about seven holes in the butt where a tailpiece could be attached.

I couldn’t guess the top wood until I had sanded it a bit. I emailed a photo of it to my friend Mike McGuire, who had recently retired as head of the Gibson Custom Shop. “It looks like red oak to me,” he replied. I took that as gospel. He did not, however, venture to guess what model guitar it might be.

I listed it on Reverb.com as possibly an early prototype, with an $18,000 price tag on it. I asked for any experts to chime in or correct me if I was mistaken. No one responded, and no one bid

Had I found a missing link? It was a thin-bodied ES-350, as I best could figure, but it still had the 25 1/2–inch scale for the missing fingerboard and nut. Perhaps this was a prototype for the Gibson Les Paul. I began to salivate.

I photographed the guitar and listed it on Reverb.com as possibly an early prototype, with an $18,000 price tag on it. I asked for any experts to chime in or correct me if I was mistaken. No one responded, and no one bid.

I placed a photo of it on my Facebook page, but even Larry Briggs, a pioneer of the vintage-guitar trade, remained silent. Larry of all people should know. Nothing. I called the renowned Walter Carter in the hope that he might recognize the serial numbers on the potentiometers but struck out there as well.

It was time to do a little detective work on my own. I looked up pawnshops in McAlester, Oklahoma, but couldn’t find a listing for Old Town Pawn. Google Maps showed Red Barn Pawn in the same location, with a photo on the front that I recognized as the former store.

I called the number, but the person who answered said he was the new owner and that Jeff McCurry, the previous proprietor, was no longer affiliated with the store.

I explained why I was calling, and as a courtesy they promised to give my number to Jeff. To my delight, Jeff called me back in just a few minutes. He did remember the guitar and who pawned it: a fellow named Ludlow Miller, who brought it in about 28 years ago.

Unfortunately, Ludlow had died, but Jeff said the man had a son, Robert, who owned a lawnmower repair business on Ridge Lane.

I found a listing for the Ridge Lane Mower Shop and was soon speaking to Robert Miller. He remembered the instrument well and told me the story behind it. His father bought the guitar - a Gibson ES-350 it was confirmed - from Floyd James, who bought it new at Culps Music Store in McAlester in the early ’50s.

Floyd was from Talihina, Oklahoma, a very small rural town on the beginning of the mountainous Talimena Drive. Ludlow used the guitar at many dances he played while accompanying a fellow named Harold Jenkins, soon to become better known as Conway Twitty.

On numerous occasions, Ludlow’s wife would go to these events where her husband was performing. Usually there was alcohol available, and Mrs. Miller would often partake of too much, get into fights and be thrown into jail. Ludlow would spend all the money he’d made that night bailing her out. This happened so often that he quit taking his wife to the jobs.

Long about 1963, Ludlow came home one night and his wife, drunk and angry, grabbed the guitar and gave it an El Kabong against a wall, breaking its body. Robert, who was about three at the time, witnessed the calamity. He remembers thinking, That guitar didn’t do nothin’ wrong - why did Momma smash it?

I can only imagine Ludlow must have turned white and nearly passed out from shock. He loved that guitar and needed to save what was left of it, if he could. Robert told me his dad had a friend at the local lumberyard named Gene DeFrange, who helped Ludlow fashion a new body out of what I surmised to be teak marine plywood and red oak floor slabs.

After the plywood was cut out on a bandsaw to the shape of the original ES-350, Ludlow glued the floor planks together, and then screwed the top and back to the side molding and carved the top contours and pickup holes with a pocket knife.

It’s a pretty good Gibson-like graduation, especially with a pocket knife. The paint job came courtesy of Herman Lolly at the local Ford dealership, who did the work in their paint shop: Ford Black on the back and Ford White on the top.

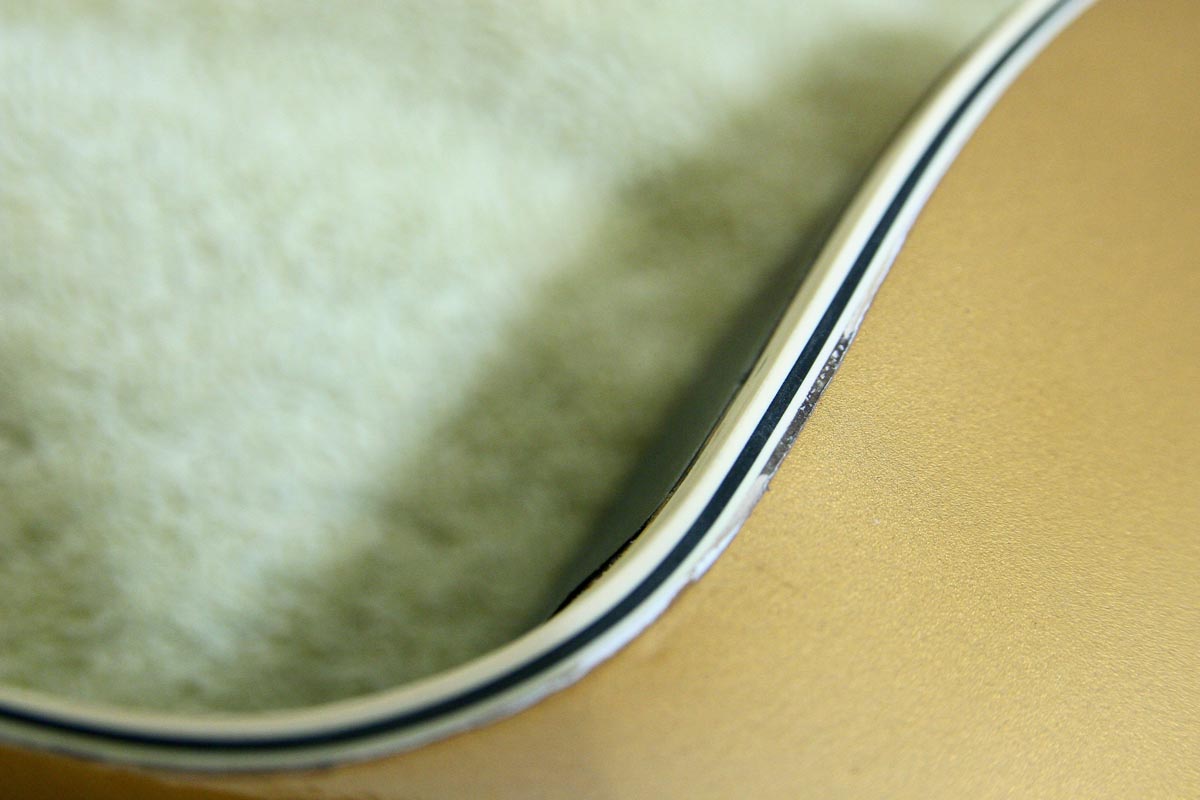

The top was routed and the original binding, which had been saved, was glued to the new carcass. Ludlow played this resurrected piece for several years, until he was no longer playing, at which point he pawned it to Jeff McCurry at the Old Town Pawn.

There was something compelling about Ludlow’s story and his devotion to this old instrument, and an inherent love or vibe in its reconfiguration. I couldn’t throw it in the fire. Besides, the timbers were now 60 to 70 years old. I decided to invoke all my restoration skills, slowly and patiently, as Ludlow would have.

I built a spray booth on my back porch and bought a compressor and spray gun, like Mike McGuire from Gibson Custom had directed me, and installed a chicken-breeder exhaust fan so I didn’t blow up while spraying lacquer.

Even though I understood the guitar originally had a Bigsby vibrola, I decided to put the proper time-period hinged ES-350 tailpiece with gold plating on it. I found a rosewood base and bridge for it and scrounged up some vintage Gotoh tuners in gold to match the original “single-line” footprints of the original tuners.

I had Virgil at WD Music make me a new pickguard after I had drawn a template around the newly placed old pickups. I hand-sanded the red oak veneer after straightening it with vinegar and hot water and clamping it in Plexiglas molds.

The sanding was done to sharpen the edges of the veneer so that I could force them into the cracks between the top pieces, where they were glued into place with Titebond. Then they were clipped off with end nippers and hand sanded down.

Holes were precisely filled with toothpicks or small dowels that were reduced in a drill to the proper diameter. The crack in the heel was filled with superglue and maple dust until it was rigid.

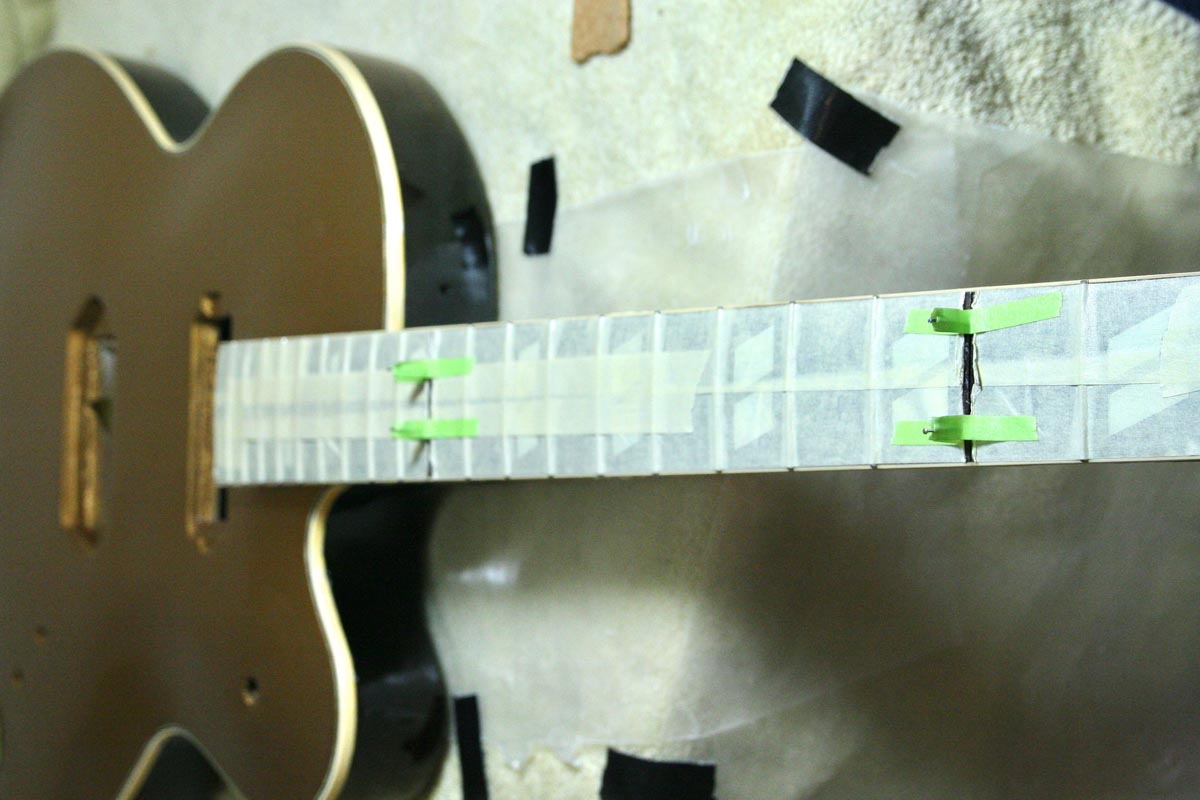

Jason Clark at Custom Inlay - in Caneyville, Kentucky - made a new fingerboard to the precise widths I called for and inlaid parallelogram mother-of-pearl blocks like the guitar would have had from the factory.

I installed the frets and sanded down the rough edges on sticky-back sandpaper placed down on my laminate cabinet top. I then glued it to the old neck with Titebond after drilling alignment holes in the 2nd and 11th fret slots with a pin router, and placing sewing pins in the holes to maintain the alignment through the slippery gluing-and-wiping process.

I decided to replicate the sunburst on the back of the neck and the back and sides, which took numerous lacquer drop fills to balance out. The top was too riddled with filled holes to attempt a sunburst, so I decided on a gold top. Mike told me what product to buy and add to my clearcoat to achieve the desired finish.

Scraping the gold just back to the edge of the binding proved to be the most difficult task of all, and I had to redo the whole top once to make it look good, but all the effort was well worth it. The guitar now looks great and will be strung up soon.

The wood has a promising deep thump to it and a resonant quality that I suspect will enhance the dynamic response from the strings. I did, however, install a solid mahogany block between the two pickup holes to help eliminate feedback from the P-90s.

Ludlow had installed a metal screw jack or adjustable sound post under the top near the bridge for the same purpose, a trick not used by Gibson until Chet Atkins and Jim Hutchins collaborated on the Gibson Country Gentleman in the late 1980s.

After I do my final polish and install the original pickups and fish the controls back into the old cavity, Lazarus, as I call him, will be ready to go out and perform again, albeit in finer form than in his original reincarnation. He will have been raised from the dead twice, both times with love and patience.

John Southern is a professional photographer, musician, and guitar designer and builder from Tulsa, Oklahoma. He has recorded four albums of his own compositions and produced Talkin’ Guitars episodes for TV about Tom Van Hoose, George Gruhn, Bugs Henderson and the Martin Guitar factory tour.

Southern has also designed the Lyrics, his own line of acoustic-electric hollowbody guitars, and completed a working prototype of his Southern brand acoustic guitar with a dry-fit, bolt-on four-bolt neck, featuring a new joint of his own design.

He deals in vintage instruments under the name Guitar Orphanage and can be contacted at johnsguitarshop@aol.com.