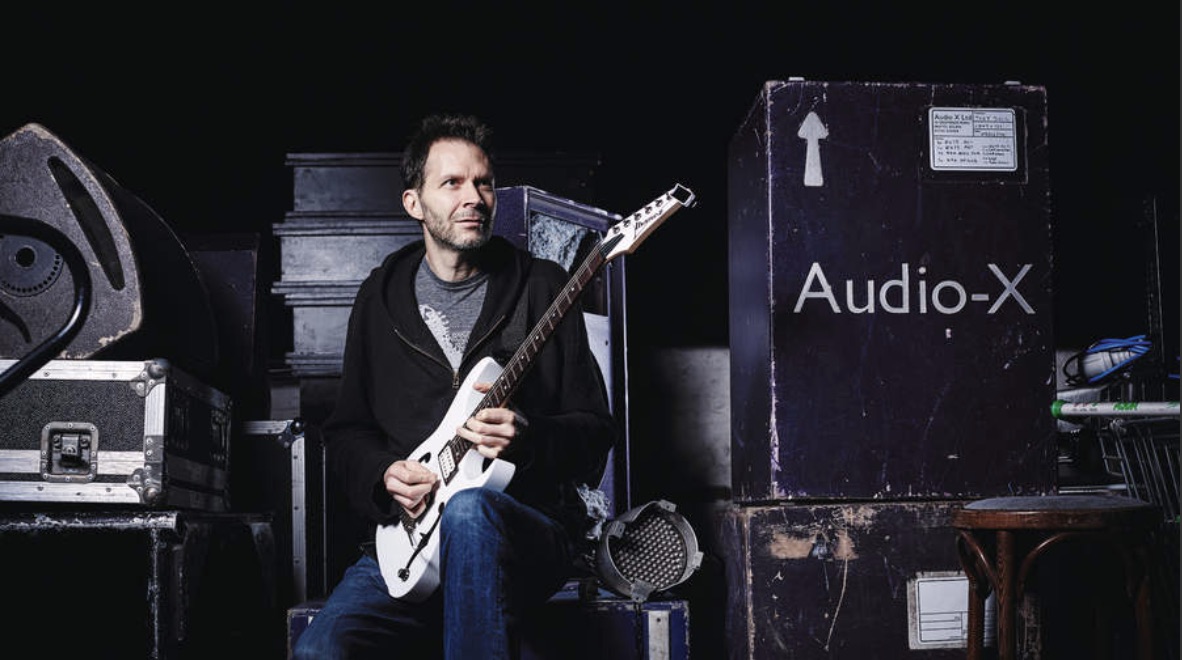

Paul Gilbert on How He Tamed His Inner Shredder and Found a New Melodic Range with Slide Guitar

The shred icon's latest album, 'Werewolves of Portland,' is playful, super-entertaining, and combines guitar pyro with melodic sensibilities influenced by the Beatles and Joplin.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Axe legend Paul Gilbert has a long association with Guitar Player. He made his first appearance in these pages in February 1983, at age 16, when he appeared alongside Yngwie Malmsteen in Mike Varney’s “Guitar Spotlight” column.

In the late ’80s, he had his own “Terrifying Guitar 101” column, an essential for wannabe shredders in the pre-internet age, when lessons in the guitar magazines, Guitar Player in particular, were saved and pored over for months.

In his many instructional home videos, it was apparent Gilbert possessed more than an uncanny facility for hair-raising guitar pyrotechnics and an off-the-wall sense of humor; he also had a gift for being able to simplify the most complex of topics.

Gilbert is still very much involved in guitar instruction and posts more than 1,000 videos a year for students in his online guitar school at artistworks.com. Having released a couple of albums with Racer X in ’86 and ’87 (compulsory listening for shred heads), he hooked up with Billy Sheehan in ’89 and found international mainstream success with Mr. Big.

Ironically, their biggest hit, the 1991 acoustic ballad, “To Be With You,” featured one of his simplest guitar solos. After Gilbert left Mr. Big in 1999 (he rejoined in 2009), he went on to forge a career as a solo artist, releasing a string of critically acclaimed records, many featuring his vocals as well as showcasing his unparalleled axework.

Gilbert’s latest release, Werewolves of Portland (Mascot Label Group), is an all-instrumental affair. Indeed, the melodies are so strong, a vocalist would be superfluous. Such was true of his previous record, 2019’s Behold Electric Guitar, and it’s a direction he seems set to continue with, as he reveals in our wide-ranging discussion about his current modus operandi.

How did you record during lockdown? Did you use a band in the studio or work remotely?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

My initial idea was to do it live in the studio with a band, like I did for Behold Electric Guitar, but because of lockdown, all my plans went out the window.

I wasn’t sure what to do, so I took time off and concentrated on my school, but I was concerned that I had to do something about the record, so I finally decided to play everything myself. I had no idea if that would work. I love playing drums but that doesn’t mean I’m necessarily good enough.

I discussed it with Kevin Hahn, who engineered it, and we agreed to try it at Opal Studios in Portland. We agreed that if there was something that didn’t work, we could bring somebody in. In the end, we only needed to use someone for a snare buzz roll. Otherwise, it was all me, and it was really fun to do it all myself.

There is a very upbeat, commercial feel to the album, with hooky parts all over every song.

I think the fact that I had a lot more time to write because the whole schedule was pushed back might well have been a factor, and I’m almost glad that it was. I had ideas, and I would have been relying on band members to help arrange things, but because I had an extra six months to work on the record, I was able to think a lot more about melodies.

Plus, after the last tour I started to get a lot more comfortable with the idea of playing melodies on guitar. That may seem like a simple idea, but to me that is a huge change in philosophy from where I began as a guitar player. I always thought melody was the singer’s job.

The players that I grew up idolizing and copying weren’t playing melodies in their solos the way Boston might have approached a solo. I was coming more from the athletic guys, like Van Halen, Yngwie, and even Jimmy Page, who tended to play solos that weren’t just based on the melody of the song.

The other thing that scared me away from melody was Muzak, which younger readers may not remember. There was actually a company called Muzak that made horrible background music where they replaced the singer with a guitar line and very often ruined the song by playing the melody in a sterile way.

I think that influenced me to believe that a guitar couldn’t play the melody with the same emotional intensity as the singer. I started to change my way of thinking after I did a tour way back in 2007 with Joe Satriani, where he played a whole show with guitar melodies. It made me re-evaluate the way that I viewed the instrument.

Does the fact that this record and the last were all-instrumental mean you aren’t planning to make vocal albums?

Playing melodies on guitar has changed my views of vocals, as a lot of limitations are taken away. I have no fear of the high notes and a better appreciation for the low notes. I would hardly ever choose one of my own melodies to reproduce as a guitar line, as the vocals don’t go very far.

If you take something like “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” by Elton John, he’s all over the place, with huge interval jumps in the melodies, and that’s really fun to reproduce on an instrument. It’s hard for me to travel a lot melodically with my voice, as I don’t have much of a range. With the melodic limitations removed by playing the melodies on the guitar, I have the freedom to go wherever I want with a song.

I never sounded good with slide for the longest time, until I had a slide that was too big for my third finger. I put it on my second finger, and my slide playing instantly transformed

There is a lot of slide guitar all over the record, although rarely in the typical blues-lick approach. Does slide give you a better way to express yourself?

Slide guitar really opens up the door to expressing emotion in a melody. I never sounded good with slide for the longest time, until I had a slide that was too big for my third finger. I put it on my second finger, and my slide playing instantly transformed – the vibrato, the tuning, and my expression.

I’d never spent much time on slide, but at that point I started working on “Mercedes Benz” by Janis Joplin and “Blackbird” by the Beatles, really trying to capture the nuances of the way they were singing, with the slide playing the melody. That led me to find my own voice. As a music fan, I’ve always listened to singers more than just guitarists.

There are so many great vocal melodies, and recently my goal became to be able to play any melody that I hear in my head, pretty much instantaneously. Think of the kazoo. You could give that to anybody and they could play something like “Happy Birthday,” or any popular melody, without any musical skill whatsoever, and you’d instantly know what they were playing.

I realized that, as a guitarist, that is actually quite a difficult skill to master. And I realized that, even after 40 years and being recognized as a shred monster, I couldn’t actually do it – I could work it out after a few moments, but not instantly. At first I thought it was kind of funny, but then I thought it was actually a tragedy. [laughs]

So I started to go through melodies in my head – maybe the Beach Boys or Elton John or someone – and try to reproduce them on the guitar. Slide is a fantastic way to do that, because you tend to work horizontally, on one string, so you can find the melody without getting into scale patterns and familiar left-hand fingerings.

Having a slide on your left hand limits your speed. Does that make you – or allow you to – look for other ways to generate intensity and emotion?

You can’t play a million miles an hour with slide, but most melodies aren’t that fast anyway. What happens is that I become very aware of who is playing. And by that I mean, Are my fingers playing, or is my inner melodic generator playing? Am I playing something that I actually hear in my head, or am I just letting my fingers run around the fretboard?

Making an instrumental record, there is no human singer, so perhaps the slide can be a singer’s voice, and then the solo can be the lead guitar player part

I like both things. I’ve spent a lot of time letting my fingers run around the fretboard, and I can stir up some excitement by doing that. I also really like, and find it really satisfying, to have a melody in my head come out as I’m playing, without working it out.

To me that is what true improvisation is. In my inner mind, I tend not to hear a wall of shred – I hear melodies. But I still do love to play fast of course. Slide makes the vibrato sound different, and it gives me another voice.

Making an instrumental record, there is no human singer, so perhaps the slide can be a singer’s voice, and then the solo can be the lead guitar player part, and I can create that conversation between the two voices rather than having the one level going through the whole song.

The opening of “Hello! North Dakota!” has a real Brian May vibe, before the main tune kicks in.

I looked up the state anthem for North Dakota and did, as you say, work out a Brian May–style arrangement. It turned out that the music was based on a piece from Haydn. In the main part of the song, I really embraced the idea of feel and tempo changes.

In fact, I did that on many of the songs, much more than I have ever done it in the past. It’s a challenge to make those changes as a one-man band. I had to plan in advance with the click track and make sure it had smooth transitions in terms of radical tempo changes. We spent a lot of time getting the click tracks right for each song, before a note was recorded.

It’s much easier to write an instrumental piece when there’s a lyric that serves as a guideline for the melodies

You often play melodies that sound like they are actual lyrics. “My Goodness” is a strong example of that.

That actually had a set of lyrics, as did most of the songs. There will be a booklet with the CD that will have all the lyrics printed in it. The line here was, “My goodness, goodness me, I’m seeing everything I never thought I’d see.”

It’s much easier to write an instrumental piece when there’s a lyric that serves as a guideline for the melodies. It lets me have strange, embarrassing, unfinished lyrics as well. [laughs] Nobody is going to hear them sung, and sometimes a lyric fragment can jumpstart the melody, and it can find its own way after that.

“I Wanna Cry” kicks off with a non-blues guitar line before shifting into a traditional blues groove, and then morphs again into a Hendrix-like funk blues. What lies behind that constantly shifting concept?

I always try to start a song off with something that will grab a listener’s attention enough to keep them listening.

I think my go-to technique for an intro is to play some kind of fancy guitar licks, and when I was sequencing the record it was hard, because so many songs started off with some kind of 16th-note phrase or fast guitar part, and I was getting tired of it.

This was initially a blues melody with lyrics, but I was wondering what I could do with it so that it’s not just playing a 12-bar blues, which has been done a lot. I felt like I needed to add some twists to it to break it up.

“Meaningful” brings a very distinct change of pace and feel to the album.

That was the first track I recorded for it. It was slow enough that I could see how playing the drums would work out, almost like a test for the whole process. I had a lot of lyrics for this one.

The melody has some really long notes, which are way easier to do on guitar than with my voice. [laughs] I really loved this when I finished it. It moved me in exactly the way that it should.

Playing bass on this was pretty challenging, as there was so much harmonic movement; I wasn’t able to sit on the root. For most of the songs on this album, I had to take that melodic approach, as there was so much going on harmonically.

Did you use anything new guitar-wise for the record?

I brought a lot of guitars to the studio, including my signature models, but I think the main difference was that recently I’ve been buying a bunch of vintage Ibanez guitars from the early ’80s.

One of my favorites is a Roadstar II; it has a very Strat-like maple neck, 21 frets, and a non-locking tremolo. When I use that whammy bar, it feels like the first Van Halen album to me, when he was still using a stock whammy. The feel of the guitar was so much like that Van Halen feel that I found it very inspiring.

What did you use amp-wise?

I wanted to record sitting next to the amps, because you hear more resonance. I used a one-watt Marshall and a Fender Princeton Reverb, and I had them in the control room with me.

I ran them clean and got my overdriven sounds from pedals. I had a big collection of effects units, but particularly important were my JHS PG14 signature distortion pedal, a TC Electronic MojoMojo overdrive, and a Supro Drive. And occasionally I used an MXR Phase 100 and a Cry Baby.

There is a heavy riff in “North Dakota” that came from trying to teach a student about syncopation

Since the start of your career, you’ve been involved in teaching, and you currently run your online guitar school on artistworks.com. What does teaching do for your own playing?

A lot of the riffs that I use to connect melodic ideas in my songs are inspired by my teaching. All the lessons that I do in my online school are basically four-bar phrases that I’ll come up with to help a student with a specific problem, be it alternate picking or whatever. It shows them how to apply the idea to music, rather than just an abstract exercise.

A lot of times I come up with phrases that I really like and that I think sound very cool, so at the end of every week I’ll go through all of the ideas and pick out my own personal “greatest hits,” and then put them on the computer. Then, if I need a part, I can scroll through hundreds of ideas. There is a heavy riff in “North Dakota” that came from trying to teach a student about syncopation.

What are the most common problems that students have, and how do you help them find their own voice?

The most common problem is how to hold the guitar. [laughs] I see so many students hold it like a classical guitar, which is fine if you’re going to play classical guitar, but if you’re going to play rock music, you need to get your thumb wrapped over the top of the neck. That’s how you’re going to get a big vibrato.

I want to teach people to be musicians. The biggest compliment I can get from students is when they say that after spending time at my school they hear music differently

The next thing is that students need to develop a really indestructible sense of time. It’s maybe boring to hear people talk about that, but if you can stomp your foot the way a drummer would play a hi-hat, and then play in time, that’s how you’re going to feel it. There is an initial learning curve, much like a drummer has, as you’re trying to play two distinctive rhythms together separately from each other.

Once you nail that, every drummer you ever play with will have a big smile, because you’ve locked into the rhythm, and the audience will have a big smile because everything you play will sound focused, and it feels really good to you as a player when everything is tied together rhythmically.

I want to teach people to be musicians. The biggest compliment I can get from students is when they say that after spending time at my school they hear music differently, in a deeper and more profound way.

What’s coming up next for you?

I’m busy with my school, almost daily in fact, seven days a week. I’m making video lessons, and that’s been a lifesaver during lockdown, as I can stay in touch with people, and it’s kept me from going insane.

I enjoy writing music now more than I ever did in my life, now that I’m writing as a singer with melodies, rather than letting my left hand dictate things. I’ve got a guitar camp coming up in July that I’m hoping will still happen, although the future is harder to predict than ever.

My school is online, so that isn’t really going to be affected by whatever might happen when live music eventually returns. I’ve been excited to find a way to record an album where the only other person who needed to be there was an engineer, so that’s given me a lot to think about, going forward.

- Werewolves of Portland is out now via Mascot Label Group.

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.