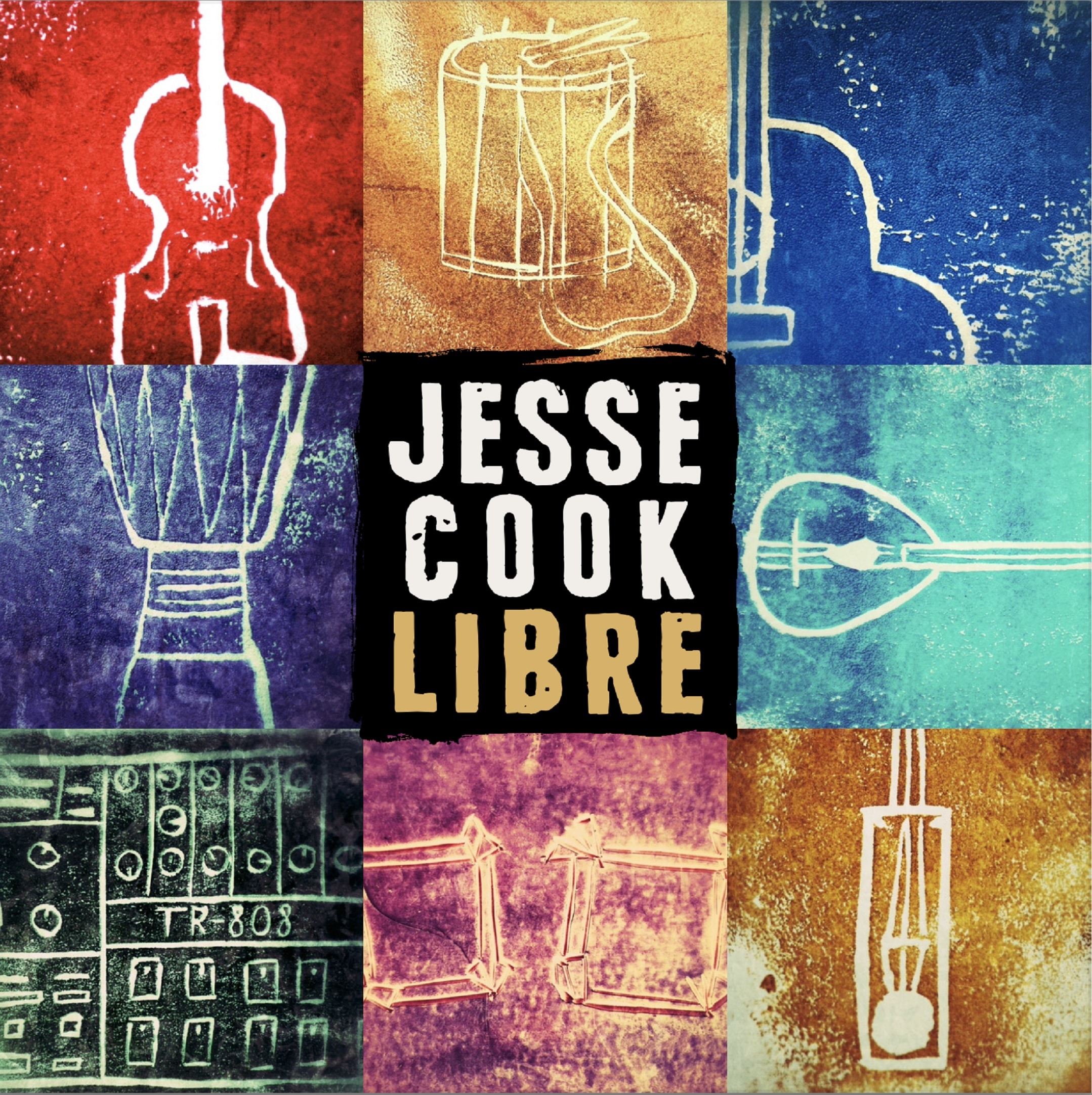

“My Music is a Reflection of My Life, Which Has Been a Little Bit All Over the Place”: Jesse Cook Talks Diverse New Album ‘Libre’

The nylon-string maestro finds release in electronic beats with his latest fret-burning effort.

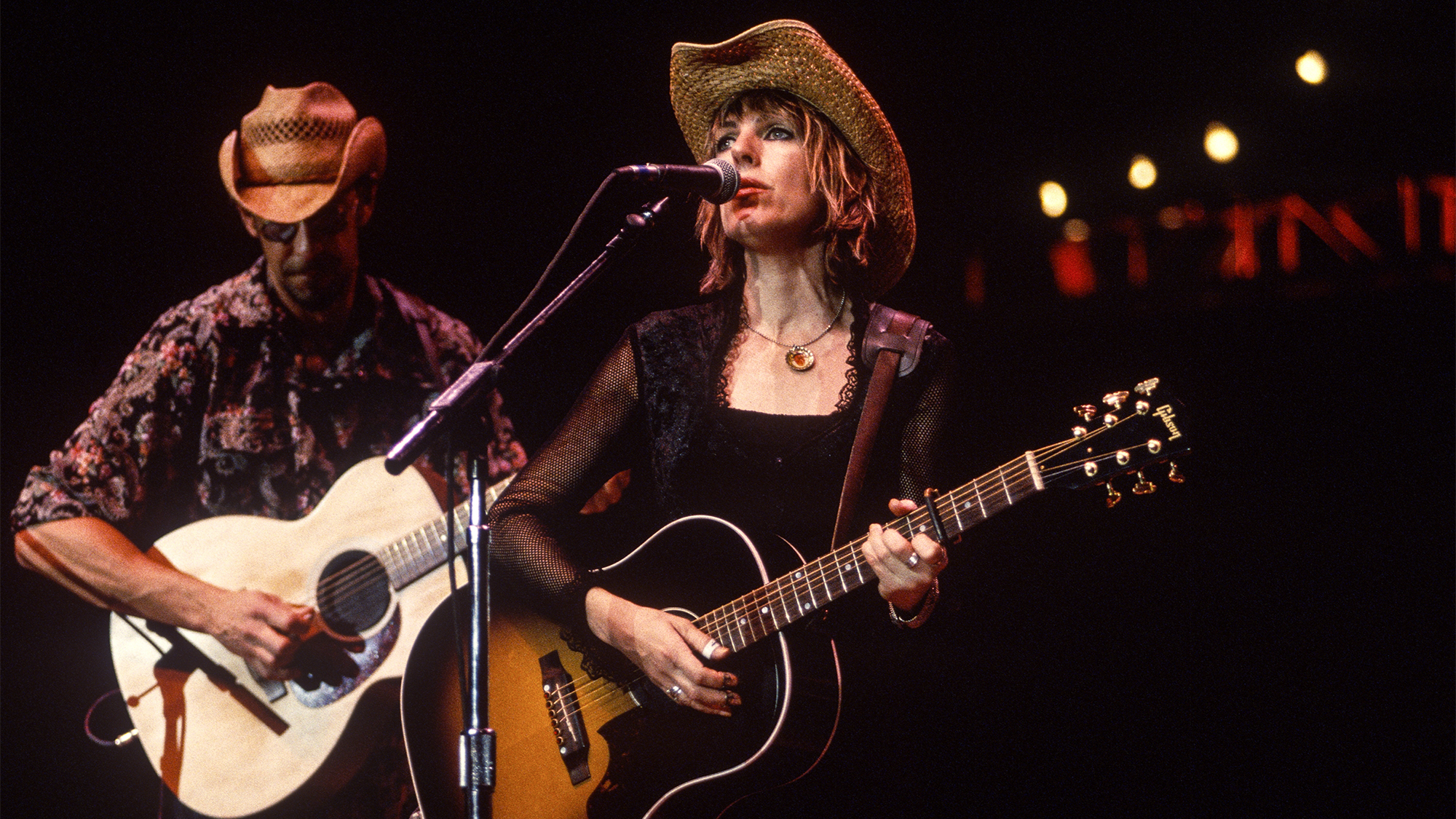

Jesse Cook crosses over to such a broad audience that he essentially flies over the radar as a guitar player. The French-born Canadian has dazzling chops and deep nylon-string guitar knowledge, yet he momentarily draws a blank when asked what pick he favors because he’s more accustomed to being addressed like a singer by the straight press than as an acoustic guitar instrumentalist by a player’s magazine.

Cook packs theaters with the general public and is more likely to be seen onscreen doing one of his popular PBS specials than on late-night talk show. His YouTube channel has nearly 100,000 subscribers and more than 25 million accumulated views, while his Spotify numbers surpass 55 million and his Pandora streams soar beyond 300 million.

Cook’s music is flamenco-inspired, but he’s not a pure-breed flamenco cat. He’s capable of playing classical, jazz and a variety of Latin styles, and his own music is a mixed bag full of all that.

Consider his latest release, Libre (One World). Inspired by the music his teenage kids listen to – from trap to lo-fi – it finds him fretting over infectious beats created via ’80s technology, namely the venerable Roland TR-808 Rhythm Composer.

Libre is a total pandemic record, conjured in Cook’s Toronto home studio with myriad overdubs and guests who bring a whole world of fretted instruments to the party.

The primary collaborator is Algerian multitasker Fethi Nadjem, who co-wrote the fabulously funky “Hey!” the trippy dark “Onward til Dawn” and the exotic “Oran” while contributing mandole, gumbri, and heavenly violin solos over the album’s length.

“Fethi can play practically any musical instrument,” Cook attests, “but I consider him a violinist foremost and kind of like an electric lead guitar player, because the violin has a similar ability to create sustained tones.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The guitarist has Nadjem in tow on his highly anticipated Tempest II tour, which finally kicked off in mid January. The stint was originally planned for 2020 to mark the 25th anniversary of his breakthrough debut album, Tempest.

Libre is a return to that early DIY approach, but the deep electronic grooves differentiate the new album from any of Cook’s 10 previous studio efforts.

Libre grabbed our attention for being a departure. Are you getting a lot of that sentiment?

So many people have said that, which is funny, because I try to make every record a departure. The first couple were rumba flamenco, and you could hear a lot of my influences, from the Gipsy Kings and Peter Gabriel to the Guitar Trio with John McLaughlin, Paco de Lucia and Al Di Meola.

After that, I started trying different things, like recording with musicians in Cairo and Columbia, and in Lafayette, Louisiana, with Buckwheat Zydeco.

Maybe this one resonates with a younger crowd because it’s infused with the kind of 808 trap beats heard in contemporary music, from reggaeton to K-pop.

Since I’ve never been properly in any one genre, I’ve always been somewhat envious of players like Paco de Lucia or Vicente Amigo, who come from and then further a rich tradition, such as flamenco.

My music is a reflection of my life, which has been a little bit all over the place.

My music is a reflection of my life, which has been a little bit all over the place

Jesse Cook

Were you always drawn to the nylon-string?

The short answer is yes. The longer story is that my family bounced back and forth between Europe and Canada. In a weird twist of fate, when my father retired to the south of France, he wound up buying the house next door to Nicholas Reyes, the leader of the Gipsy Kings.

In addition to hearing them, I’d hear local kids in the street playing that way. They were treating the guitar as a percussion instrument, and I remember just loving it. That was totally my thing.

Toronto is a very multicultural city, and when I was a young musician there, I studied all sorts of drums and percussion from India, Brazil and West Africa.

I liked the sound of the steel-string, but it wasn’t my instrument

Jesse Cook

I also studied at Berklee College of Music, and they didn’t want to teach me on nylon, so I got a Les Paul and learned to play jazz and rock music with a pick.

But at home I always wrote and played nylon-string, because you can say very different things on such a different instrument. My first lessons were in flamenco, but as I got better, my teachers steered me toward classical.

I developed a lot of fingerstyle facility, and playing with fingernails on a steel-string would shred them. I liked the sound of the steel-string, but it wasn’t my instrument.

What nylon insights would you share with all the steel-stringers out there?

There are lots of different kinds of nylon-string players, and the most common misconception is that people envision flamenco as being classical, when in fact flamenco guitars are actually quite different from classical guitars.

Classicals have a big, warm round tone, whereas flamenco guitars have a bit of a buzz to them.

There’s an X factor to a flamenco guitar that’s like tobacco or coffee, and an array of different ways to hit the soundboard as you play, called golpes.

Classicals have a big, warm round tone, whereas flamenco guitars have a bit of a buzz to them

Jesse Cook

Steel-string players recently started tapping on the guitar, but that kind of pounding on the box has been around in flamenco for hundreds of years in order to compete with the pounding of dancers’ feet, hands clapping and people singing at the top of their lungs.

The nylon-string gets a bad rap as being a little bit dainty, but it’s not – it can be nasty, and I love it. Having a bit wider neck allows more room for your fingers to cover different things simultaneously.

Can you dig deeper into the evolution of flamenco?

Another misconception is when people hear salsa, Latino music; they might think that it’s flamenco when it’s actually not. Flamenco is originally gypsy music from Andalucia, southern Spain. Keep in mind that the guitar originally comes from Spain.

Luthiers there have been making guitars for hundreds of years, and even back then the great luthiers would make classical guitars out of the most expensive woods, like rosewood. Gypsies came along looking for something less expensive, so luthiers would use cheaper, brighter woods like cypress.

Flamenco is all about being able to pound the instrument to create a rhythm that sounds like a full band

Jesse Cook

They would also make the top much thinner than a classical, and with much lower action. The bridge is rather small, so you can hit the wood of the guitar face with your finger and your nail, while also hitting the string. Do that on a classical and when your nail hits the face wood, the string hits kind of in the middle of the finger and rips the skin off. It’s awfully painful.

Flamenco is all about being able to pound the instrument to create a rhythm that sounds like a full band.

Over time, people came to like the sound of those cheaper woods, and the luthiers started to refine it. Nowadays a spruce or cypress guitar made by a great Spanish luthier like Reyes costs 20,000 Euros.

Negras like what Paco famously played back in the day have the warmer sound of rosewood back and sides. Blancas, or blonds, like the kind Vicente Amigo and I prefer, have spruce or cypress back and sides. In recent years they’ve gone from being used mostly for rhythm accompaniment to becoming featured concert guitars.

What’s your favorite guitar?

My favorite is made by Conde Hermanos, which means “Conde Brothers.” Spanish lutherie historically goes back to the Ramírez shop, and you can trace the Conde’s lineage back to it in the early 1900s.

When I bought my first concert guitar in Spain, there were three different Conde shops all claiming to be the one where Paco de Lucia bought his guitar. [laughs] I eventually determined that Conde Hermanos was indeed the one.

Spanish lutherie historically goes back to the Ramírez shop

Jesse Cook

They have since split up, continuing the tradition of the tree of great guitar makers splintering into further branches, and nowadays everybody’s playing the Felipe V [five], made by Felipe Conde.

My main live performance guitar is one I found at the Guitar Salon in Santa Monica, California. It’s a blond with a cutaway, made by German Vasquez Rubio. I use D’Addario EJ46 Pro-Arté strings.

Can you encapsulate your plucking approach?

My right-hand approach is weird because I studied flamenco and classical playing with my fingers, and jazz with a pick. The funny thing is that I think jazzers like it when you play with your fingers, but flamenco people hate it when you play with a pick. [laughs] It’s like sacrilege.

I bounce back and forth, depending on the situation and the song. When I really want to soar over the band onstage, I’ll play with a thick Dunlop Americana Round Triangle pick to get that attack with as close to a warm, flesh-and-fingernail sound as I can come, and think of it more like a jazz solo.

When I really want to soar over the band onstage, I’ll play with a thick Dunlop Americana Round Triangle pick

Jesse Cook

I play fingerstyle when the situation is what they call in flamenco a falseta, covering the melody and the bass and the chords simultaneously. I play with my fingers the vast majority of the time in the studio.

I’m much more likely to use a pick live when there’s more improvisation. You can go pretty fast playing single-note scales using a picado technique, plucking with the first two fingers. Paco’s picado was ridiculously fast. I need a pick to get into that extra gear.

My earlier records had flashier guitar playing, whereas now I’m more interested in taking people on a journey. When you put on a record, you want to kind of live in it, with room to move around. You don’t want to listen to somebody play 64th notes in your living room.

When you go to a concert, you want to have your socks knocked off.

The opening cut on Libre, “Number 5,” sounds almost like an exercise in not playing flashy.

Yeah, I was trying to take it to a lo-fi place, and I don’t mean low fidelity. Lo-fi music has a chilled-out vibe and kind of a jazzy nostalgic sound that often includes creaky samples of old music.

The feel is quiet, but very interesting, like Bill Evans. There’s an element of reggaeton in the 808 beat behind it, but the guitar has more of a Cuban vibe, like Buena Vista Social Club.

Whether it’s a ballad like “Solace” or an up-tempo cut such as “Updraft,” it sounds like you start by creating almost a duet with yourself playing rhythm and melody guitar tracks, and then add organic and electronic elements to create divergent soundscapes.

Right, I do build all my songs kind of the same way. I sit in my home studio and play all the parts. I have lots of percussion, drums, basses and synthesizers.

People think of me as a guitarist, but I actually majored in music synthesis at Berklee

Jesse Cook

I’ve always loved doing sound design. People think of me as a guitarist, but I actually majored in music synthesis at Berklee. I love synths, and all the sounds and textures you can build up using a computer.

I use Apple MainStage in my live rig as well, and so does my second guitarist, Matt Sellick. We have these pretty insane rigs, so we can play synths and pure nylon-string sounds simultaneously.

How does your signal chain flow?

I have RMC [saddle] pickups and a microphone inside my guitar running through separate outputs, plus a multi-pin output sending MIDI information to a Roland GI-20 interface. All three feed into a computer running Apple MainStage.

I use that as a mixer to add effects downstream and also trigger whatever I want synthesized, such as, say, a Bollywood string section to run in unison with a lead line.

I always find it weird when I see someone playing a guitar and hear something else, but I like it when there’s something else behind it, enhancing. I don’t like it when acts sequence shows to backing tracks either, so we’ll use drum triggers to get the 808 sounds.

The concert experience is truly remarkable

Jesse Cook

What are you looking forward to most about getting back into the live arena?

You take it for granted when you tour all the time, and then when it’s suddenly all gone, well, at first it’s a release. You don’t have to worry about changing your strings or getting your guitar serviced for whatever broke on the last tour, and it’s nice to be with family. But then you miss the magic of playing live music with band members bringing in ideas, rather than having them all bounce around in your own head.

I’m looking forward to having that conversation with the audience, where you’re making music and sometimes they sing it back to you, or maybe you do it together. You start to forget after two years away, but the concert experience is truly remarkable.

Buy Libre here.

Jimmy Leslie is the former editor of Gig magazine and has more than 20 years of experience writing stories and coordinating GP Presents events for Guitar Player including the past decade acting as Frets acoustic editor. He’s worked with myriad guitar greats spanning generations and styles including Carlos Santana, Jack White, Samantha Fish, Leo Kottke, Tommy Emmanuel, Kaki King and Julian Lage. Jimmy has a side hustle serving as soundtrack sensei at the cruising lifestyle publication Latitudes and Attitudes. See Leslie’s many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, dig his Allman Brothers tribute at allmondbrothers.com, and check out his acoustic/electric modern classic rock artistry at at spirithustler.com. Visit the hub of his many adventures at jimmyleslie.com