Lyle Workman on Taking the Road Less Travelled and Finding His Own Musical Identity

Workman reflects on finding his own sound after over three decades as a sideman, session player, and film music composer.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Listening to “North Star,” the nine-minute-plus opus on Lyle Workman’s record, Uncommon Measures (Blue Canoe Records), you feel like you are hearing the overture to an epic, exciting movie, perhaps one about pirates, cowboys, or even a galaxy far, far away.

Searing slide guitar slips into sections of skittering strings and fusion flurries that are followed by heralding brass parts. There’s even a drum solo. The miracle is that, like a great movie overture, the disparate elements hang together with an overarching theme.

Elsewhere on the album, Workman plays Django-style acoustic, country twang, and chiming pop riffs. Is there anything this man can’t play? “If there was any difficult classical guitar, that would be an area I’m least qualified in,” he says. “I would have to spend six months practicing only that.”

Workman’s career is easy to envy: gigging and/or recording with Sting, Beck, Todd Rundgren, Bootsy Collins, and Frank Black, as well as writing the music for a series of major movies, starting with Judd Apatow’s 40-Year-Old Virgin and continuing through Superbad, Forgetting Sarah Marshall, and others.

It should be noted though, that his achievements are less about luck than a combination of hard work, drive, and chutzpah. When Frank Black asked him what he was doing for the next couple of months, Workman responded, “Playing with you.”

With such a varied skill set and résumé, it's not surprising that Uncommon Measures draws from myriad musical and cinematic influences. What is surprising is how it reflects a unique and consistent point of view.

Speaking in depth about his career, Workman reveals how he was able to cohere his wide-ranging inspirations, the joys of power-amp distortion, and where it all began: with a father who played for fun and introduced him to the instrument.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In Workman’s teens, a teacher schooled him in the modes and set him working his way up and down the neck learning arpeggios. This began the fledgling player on the road to the amazing technique he evidences on Uncommon Measures.

“I was always trying to play difficult stuff,” he reveals. “I was really into Steve Morse and John McLaughlin. When trying to work up a riff, I would use a metronome to try to increase the speed.”

Two years of college, studying theory, composition, harmony, and sight reading taught him to put names on the things he could already play. “It had all been learning how to play things by ear off of records,” he says.

A stint with the Bay Area band Bourgeois Tagg led to a gig with Todd Rundgren, who had produced the band’s second record, 1987’s Yoyo, which featured the Workman co-write “I Don’t Mind at All,” a gorgeously shimmering song with Beatles-esque harmonies and strings.

Rundgren subsequently asked the band to play on his own Nearly Human album. When Bourgeois Tagg broke up, three of the members, including Workman, toured with Todd.

Another Rundgren record, Second Wind, was recorded over four nights at the San Francisco Performing Arts Center. “We did that record in front of people, set up onstage the same as we would be in a studio,” Workman says. “They were instructed to be quiet until given a signal before applauding.”

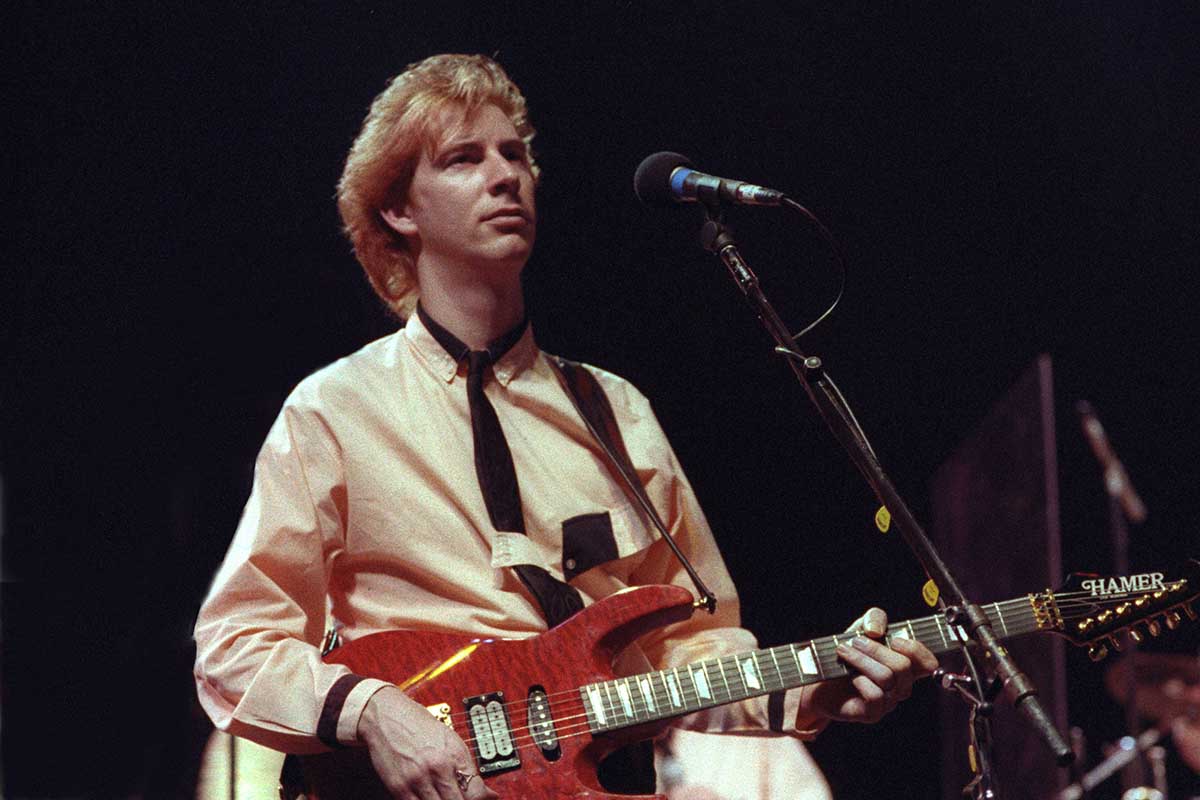

Around this time, Workman was introduced to Joel Danzig from Hamer Guitars. “I signed with them as an endorsee and played Hamers through my time with Bourgeois Tagg and then in Todd’s band,” he says. “I was largely playing Mesa/Boogie amps, but with Todd I had a Kasha preamp I would run into the power amp section of my ’69 100-watt Marshall.”

Workman’s place at the top of the sideman heap continued as he played with Beck from 1999 to 2001 and was later recommended to Sting. “I flew out to New York, we played a bit and I got the job,” he says casually.

“We did some recording and a pretty extensive tour during the summer of 2006.” Pre-tour, he did his first Sting gig ever at Live 8, in front of tens of thousands in person, and millions on TV. “It was wild,” he recalls. “I’m backstage and there’s David Gilmour and Pete Townshend.”

The band was a quartet, with Workman and Dominic Miller, Sting’s band member for the past 20 years, sharing the guitar duties. “Dominic would say, ‘I’ll take this, you take that,’” he explains. “He’s a very generous guy and welcomed and supported my role in the band, and so I really enjoyed it.”

Playing a Telecaster on that tour helped him get the Andy Summers sounds, but that Fender model was already a staple of Workman’s arsenal. “I have 1972 Thinline and 1955 Telecasters,” he says. An old Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Electric Mistress, a Line 6 Delay, and an EBS bass compressor were run through a Divided By 13, an amp company whose products often enhance the guitarist’s sound.

“Their amps are organic and responsive,” he says. “They are great clean but also do the lightly broken-up and mid/gain thing well. That’s the area that really tells how good an amp is – when the gain that comes in first is not ratty but has a full sound with smooth breakup.

"I’ve come to realize that I like power-tube distortion, not stages of preamp gain. It’s easier to hear yourself.” Workman keeps the stage volume tenable by using relatively low wattage – he owns 15, 23, and 38-watt models – but maintains that they are all loud enough.

It may seem a no-brainer for a guitarist of Workman’s technical ability and range to play with musically sophisticated artists like Bourgeois Tagg, Todd Rundgren, and Sting. It is harder to get one’s head around where a punk icon like former Pixies founder Frank Black fits into the picture.

“I like all kinds of music,” Workman explains. “I do session work with Michael Bublé and an orchestra, and then I’m playing with Frank Black, with people moshing and stage diving. Punk rock is as valid as jazz or any other music if it has integrity and a unique quality that is expressive. Frank Black’s music is deep. There are left turns all over the place and interesting chords. I loved the Pixies and the first Frank Black solo record.”

True to form, Workman uses a ’69 Tele with Black. “I’ve got Barden pickups in there,” he says. “I didn’t want noise.”

Workman’s first solo record, Purple Passages, was recorded in his Bay Area bedroom studio with an eight-track and a Soundcraft board, used programmed drums and the occasional GL300 guitar synth. His second record, Tabula Rasa, has more soundtrack-like elements, partially prompted by a move to Los Angeles.

There he started working for a jingle company, gaining his first experience writing to pictures, but the record’s string arrangements recall cinema more than commercials. “I am a film buff and was listening to John Williams, Jerry Goldsmith, and guys like that, paying attention to what they were doing,” Workman says.

To train for the movie scoring that helped prepare him for Uncommon Measures, he took an extension class at UCLA when he moved to Los Angeles. “It was about film scores particularly, but it’s the same information and I learned a lot from that course,” he explains.

“I also learned by working with orchestrators. You have to know there are certain things you don’t do because they don’t sound right, but you embellish that with knowledge from great teachers.”

As a sideman, session player, and film music composer, Workman fulfills someone else’s vision as his day job. But when creating his solo work, he allows himself a wide range of creative freedom to fulfill his own vision.

Almost any melody is going to sound better with a slide. I love the sound of it, particularly the way George Harrison used it

“I love collaborating, but when I do my own music, I don’t start from any point of view,” he says. “I don’t have a concept. I give myself the freedom to let something happen naturally, and that’s what gets developed. The only agenda for Uncommon Measures was that I wanted to bring my orchestral writing experience to my music.”

And bring it he did, employing a 63-piece orchestra at London’s Abbey Road Studios. The orchestra was recorded after Workman and a variety of session aces, including Vinnie Colaiuta, Matt Chamberlain, and Tim Lefebvre, laid down the band tracks. “The orchestra is always last,” he explains. “You want to know exactly what they are doing, because it’s very expensive.”

The Uncommon Measures track “North Star” features a violin solo by Charlie Bisharat that recalls Workman’s Mahavishnu Orchestra influence, yet it’s but one of many inspirations that infuse this wide-ranging work.

“I think you reach an age where everything comes together into a point of view that seems singular, even though there are different styles when we break it down,” he says.

One style that appears often is slide guitar. “Almost any melody is going to sound better with a slide,” Workman says. “I love the sound of it, particularly the way George Harrison used it. His tone and way of playing melodies is unique.”

Acoustic guitar parts and solos also abound. Workman’s enviable acoustic arsenal includes some ’40s Martins, a Gibson LG-2, a ’50s Gibson J-50, and a Guild 12-string. For acoustic solos that require access to the upper fretboard, he has a Jeff Traugott with a cutaway, as well as the instrument favored by one of the greatest acoustic players ever.

“I have an Altamira, D-hole Django-type guitar,” he says. “I fell immediately in love with it. I could never figure out how Django was able to bend strings but discovered he used light strings with high action.”

There is often a mallet instrument doubling Workman’s blistering electric solos. One might think it is a guitar synth, but it is in fact first-call percussionist Wade Culbreath reading a transcription of the guitarist’s solo. “I got that idea from Ruth Underwood on Zappa records,” he says, revealing yet another influence.

I would go back out with Sting in a heartbeat. I would love to participate with Peter Gabriel in anything, including moving his barbells from his basement to his attic

Workman’s electric guitar solos are soaring but not overly saturated. “I’ve got a modified ’69 100-watt Marshall, which has a good amount of preamp distortion,” he says. “It’s got a pull gain and a treble boost. I also have a ’72 50-watt that I like to combine with the Divided By 13 heads. I always prefer distortion coming from an amp, as opposed to pedals.”

If you search “Lyle Workman” on Spotify, you will find, in addition to his four solo records and soundtrack albums, a series of compilations with titles like Titans of Metal, The Pleasure of Your Company, Soar, and Acoustatic. These are yet another outlet for this musician’s seemingly boundless creativity.

“About five years ago, I was hired by Facebook to be part of what they call the Sound Collection,” he explains. “It’s license-free music for Facebook users to add to their personal or advertising videos. It was started by two old friends. The great thing is we don’t have to give them hit singles. We write in different genres, and I can go as far out as I want because all kinds of people listen to this music.

“I’ve written over 150 pieces in five years, in between working on films and TV. The EPs and albums on Spotify are collections of that music. Facebook allows us to put the music up on streaming networks as promotion. Three songs I wrote for that program are now on my record because they ended up being too good.”

It’s not unusual for a 21st century guitarist to wear many hats. Diminishing revenues in each area require numerous income streams to make a living. What is unusual is for one musician to do so many things at such a high level. Workman’s secret is just being true to his vision.

“If I were marketing myself, it would be hard, because it’s not only one thing,” he says. “I’m not like Joe Satriani or Steve Vai, where it’s so clear what they do. I just let whatever comes out of me become what it is.”

Currently able to support his family composing movie scores largely in the comfort of his own home studio, could the guitarist be lured back on the road someday?

“I would go back out with Sting in a heartbeat,” he says. “I would love to participate with Peter Gabriel in anything, including moving his barbells from his basement to his attic. It’s all about the music. I’d rather be a tiny cog in the biggest, most beautiful wheel than a gigantic cog in a decrepit wheel.”

- Uncommon Measures is out now via Blue Canoe