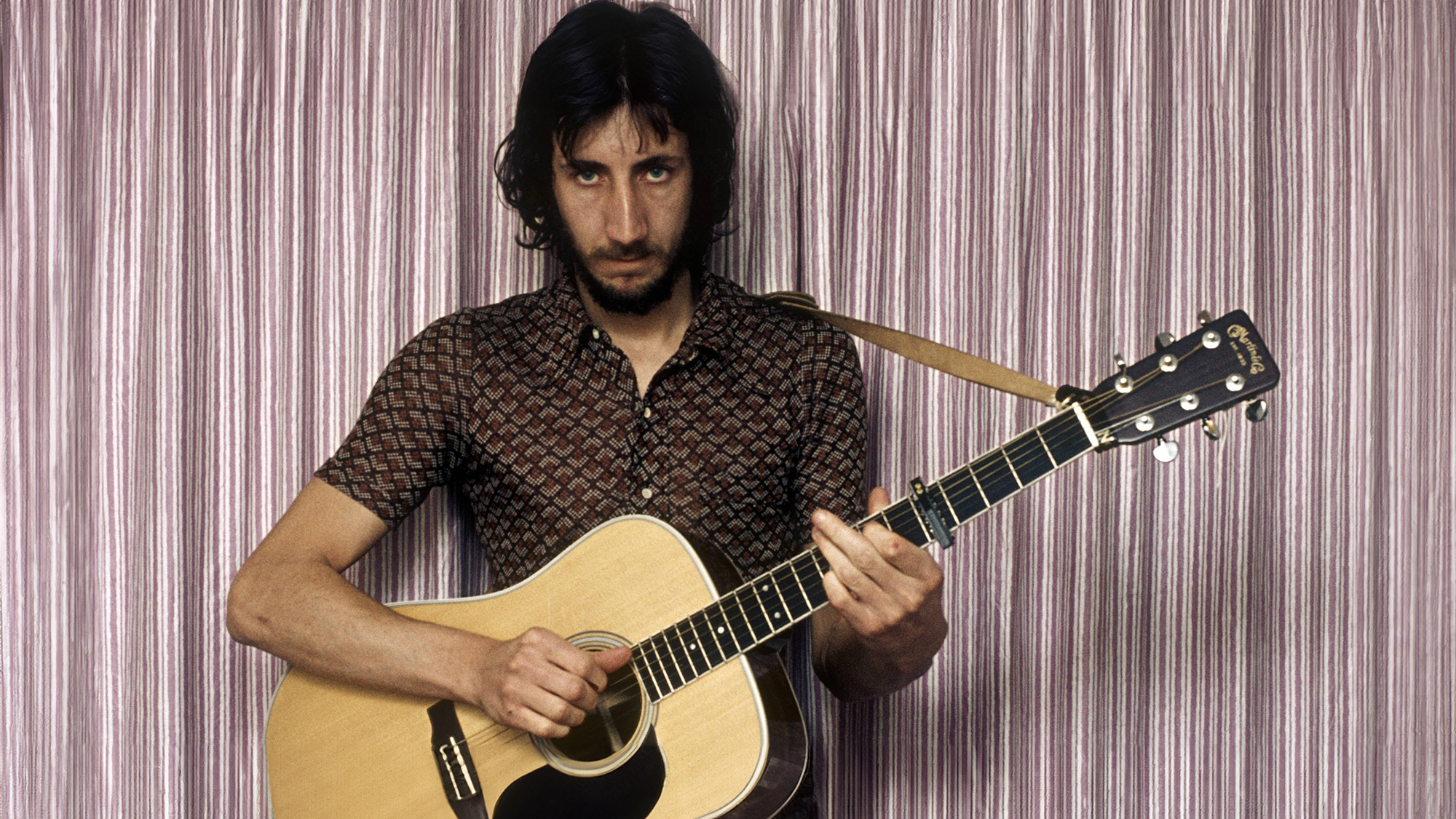

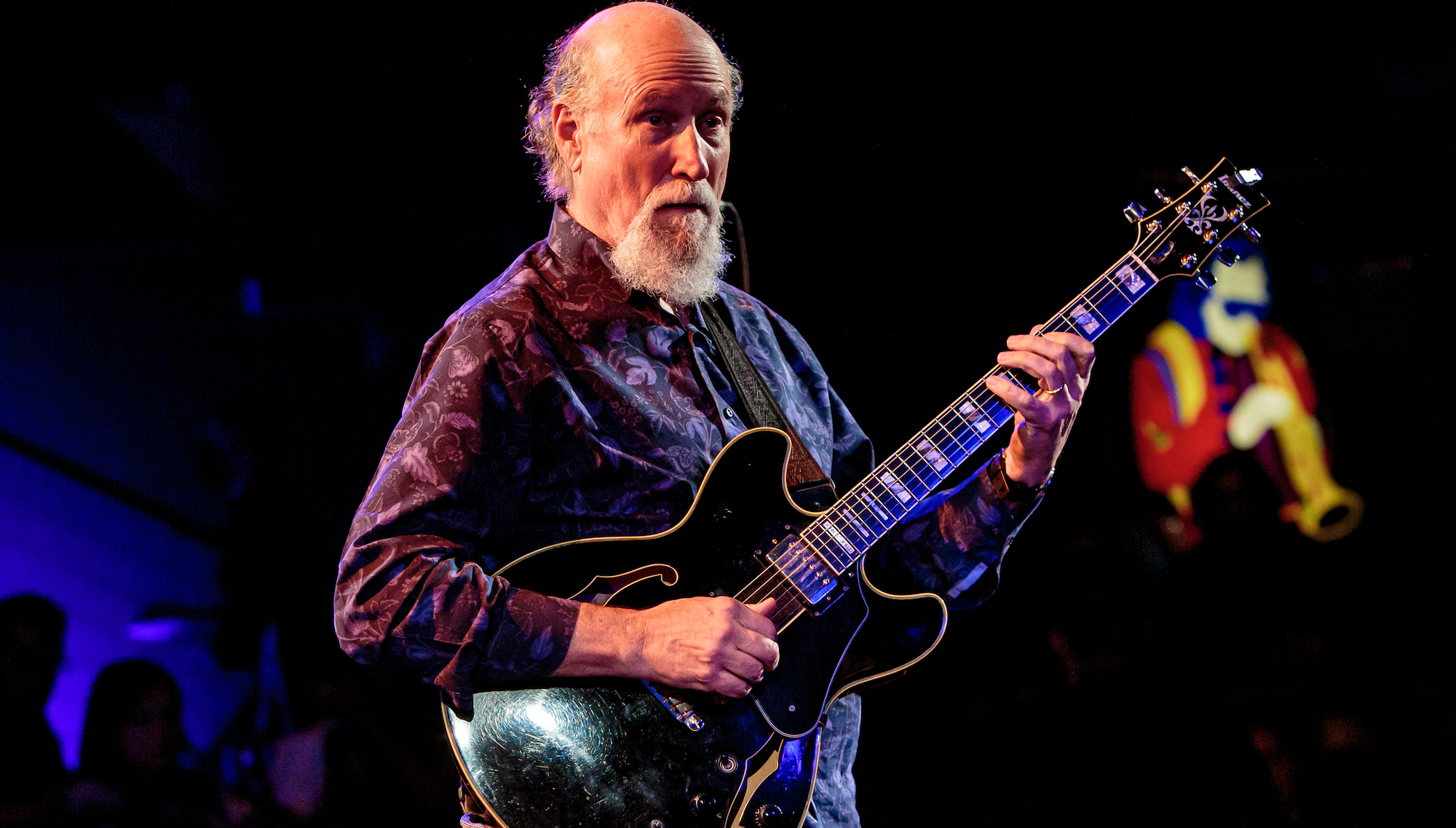

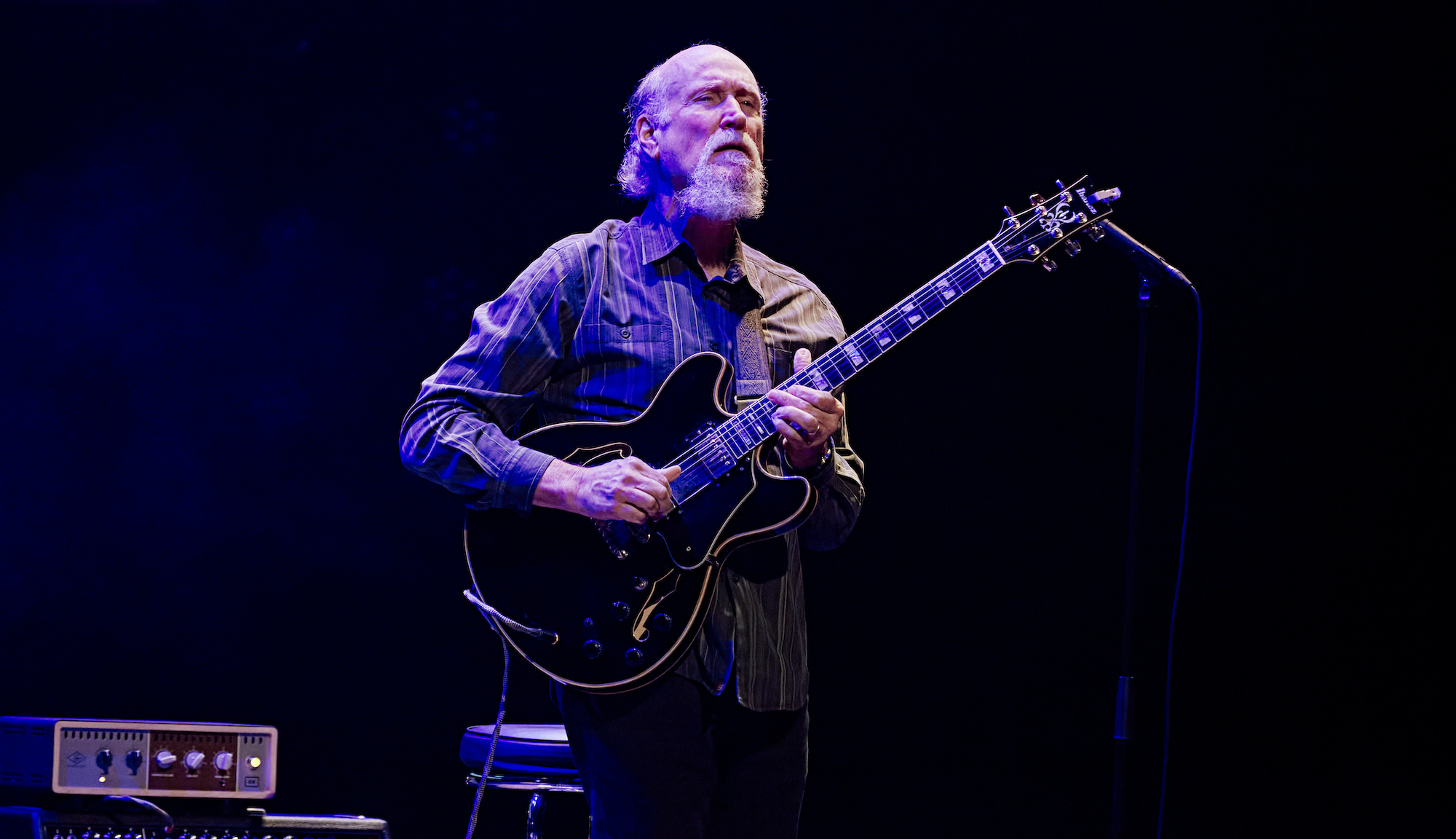

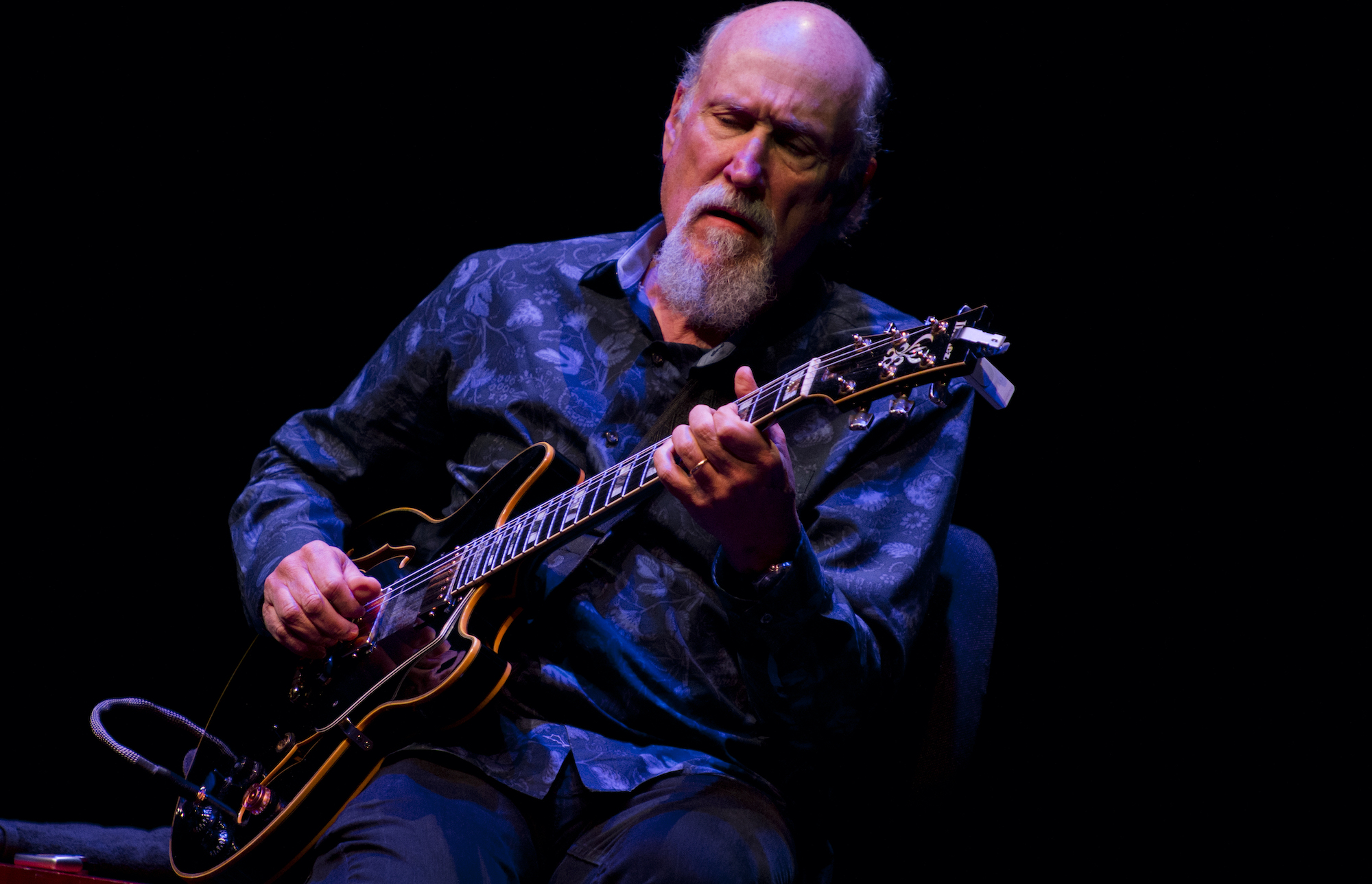

John Scofield: "You Gotta Bend the Notes – that’s Part of Our American Tradition!"

The jazz guitar master reveals how – after nearly 50 years and more than 40 albums as a band leader – he finally went solo, and revisited his musical roots, on his new, self-titled album.

In an incredible career that spans nearly 50 years, John Scofield long ago established himself as one of the Big Three of modern jazz guitar, along with his colleagues Pat Metheny and Bill Frisell. But unlike those players and many others, he had never made a solo record. As Scofield tells Guitar Player, “That’s not what I do.”

Instead, over more than 40 albums as a band leader, Scofield has led a number of lineups through a career marked by many unpredictable changes. He played advanced post-bop jazz from the late ’70s to the early ’80s, explored funk during his mid-to-late 1980s Gramavision years (a period that overlapped with his high-exposure tenure with Miles Davis), and trod jazzier terrain during his time with Blue Note, from 1990 to 1995.

There followed a stint with Verve that saw him stretch out in a number of new directions, including acoustic guitar with horn section (1996’s Quiet), an ultra-funky organ-fueled encounter with jam-band godfathers Medeski Martin & Wood (1998’s A Go Go), alternative rock-funk (2000’s Bump), and jazz (2001’s Works for Me with bassist Christian McBride, pianist Brad Mehldau, alto saxophonist Kenny Garrett, and legendary drummer Billy Higgins).

The mercurial guitarist subsequently took his music into edgy rock-funk drum ’n’ bass territory on 2002’s Überjam, which found him experimenting with wild backward guitar effects on the title track and the aptly named “Acidhead.”

The years since have seen him return to a more straight-ahead setting (2004’s EnRoute), explore earthy funk again with a crew of real-deal funkateers that includes saxophonist David “Fathead” Newman, drummer Steve Jordan, and vocalists Aaron Neville and Dr. John (2005’s That’s What I Say: John Scofield Plays the Music of Ray Charles), and make a knees-deep excursion into New Orleans music (2009’s Piety Street).

He debuted on Decca in 2011 with the gentle ballads album A Moment’s Peace, interpreted country tunes on 2016’s soulful Country for Old Men, and explored the music of Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Jimi Hendrix, and the Band on 2017’s Hudson. Now, after all of those band settings and styles, Scofield has pared it down to just himself, his trusty Ibanez AS-200 guitar, and a Boomerang Looper on his second ECM album, the unaccompanied John Scofield.

Recorded at his home in the Hudson Valley during the pandemic, this intimate solo album finds the 70-year-old six-string icon digging into his own past as he addresses the jazz standards, rock and roll, funk, and country tunes he grew up with, along with a healthy dose of the blues, all delivered with typical grace and that omnipresent vocal string-bending quality that has always been a key part of his guitar vocabulary since he began working professionally 50 years ago.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Guitar Player spoke to Scofield by phone on the eve of him hitting the road to perform duets with his old friend, bassist-composer Dave Holland.

You’ve been such a band guy all your life. Where did the idea of this solo album come from?

"I did a few short tours of Europe prior to the pandemic. I had never done that in New York, though I did some college gigs around Boston. Initially, I was thinking about it more just to do gigs. I hadn’t really thought I wanted to do a solo album because the idea of going into a studio and playing all by myself and having to get it done in studio time and having that pressure just wasn’t appealing.

"At first, I was nervous playing these solo gigs. I’ve done a few over the years, even pre-looper. And those were fucking awful. I was lonely on the road, and just the idea of playing guitar by myself seemed weird to me, so I didn’t want to do it again. But then when I got into the looper, which was many years ago, it changed my attitude entirely.

"I’ve had fun with that at home. And then a couple of years before COVID, the opportunity came up to do solo gigs, and I started to really get into it and enjoy it. But as I said, I never really thought about going into a studio and putting a solo album together. There were always too many good band things that I wanted to do. But during COVID it was the only option. So I did it."

I just recorded the whole album on GarageBand, believe it or not

And you recorded this new album at home?

"Yeah. I bought some equipment that made it possible. You know, it’s easy to do now, and the way I did it was with the Universal Audio OX [Amp Top Box]. You plug your guitar into the amp – I used my Fender Deluxe Reverb – and the amp goes to the OX, which goes into your interface, which goes into your computer.

"I just recorded the whole album on GarageBand, believe it or not. But then I gave it to a very good engineer, Tyler McDermott, who tweaked it. And finally, [ECM Records founder and producer] Manfred Eicher went into the studio with it too. So those guys made it sound better. But I really am the worst at any kind of technical shit, so this was really stupid-proof.

"I mainly got the OX because it’s also an attenuator, so I could practice at home with my amp without being too loud and still get a little bit of a fat sound."

Get some crunch without the extreme volume.

"Exactly. And then I thought it would be valuable on gigs too, where my amp is always louder than a jazz rhythm section, because I’m trying to get it to sound good. So I bought the OX and it ended up making it possible to record this solo record at home. One thing led to another. But I would never have done if it weren’t for the pandemic, I don’t think. I wouldn’t have done it at home, and I wouldn’t have taken the time to get the equipment together."

Although for years you’ve been doing those extended solo intros to tunes on the gig. [The earliest example of Scofield recording in an unaccompanied solo setting comes on “Melinda,” an Alan Jay Lerner standard from 1981’s Out Like a Light.]

"Yeah, sure, I have been. That’s the thing with solo guitar: It really works great in a rubato setting. But it’s difficult to get hot and play with some rhythm, which you can do on solo piano because you have the two hands and you can comp with your left hand. But it’s difficult on guitar, and you have to jump through all kinds of hoops to do it. And I just don’t have that ability like a Joe Pass does. But once the looper came in, it allowed me to do that. But yeah, I could’ve made a record of rubato guitar, which is just not that thrilling to me."

What were some early examples of looping that you remember?

"Well, of course, Bill Frisell was the first. He had that [Electro-Harmonix] 16 Second [Digital] Delay pedal. The looper that I have is the Boomerang Phrase Sampler +, which is one of the early Boomerang things. And it doesn’t remember any loops, so you have to make it on the fly and then work it.

"I didn’t want to be like the busker who’s down in front of the shopping center playing 'Stairway to Heaven' with an entire track behind him. No, I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to make it a little more organic than that. So I’ve got all kinds of ways of covering up that I’m making a loop. I try to make the loop sound good for the 30 seconds that I’m making it before I start playing over it, rather than stacking the whole thing."

So the loops do not decay?

"No, they don’t decay, but I can’t store loops. I make one loop, and if I want to make another one, the previous loop that I made goes away. So it doesn’t give me the option of playing a gig with 10 presets of the 10 songs I’m going to play on loops."

So, for instance, how did you do that swinging tune “Elder Dance,” which sounds like Bucky Pizzarelli comping for Barney Kessel?

"On that, I made a 12-bar blues loop that just swung, then I played over it. And that keeps up until it goes wacky, where I turned it into reverse and started to play free over it. The Boomerang can go into reverse by just stepping on a pedal. You can go into half time or double time or reverse all by just stepping on it while it’s going, which I utilize as a live function."

It sounds like there’s some kind of pedal-point looping on “Trance De Jour,” almost like a McCoy Tyner kind of a vibe.

"Yeah, exactly. It’s just an E pedal. That’s the one where I made a five-bar loop but improvise in four-bar phrases so that it sounds longer than the five-bar loop. Because at the beginning of a four-bar phrase that comes around, the comping is different every time."

You do actually perform some solo pieces without the looper, like on “Danny Boy,” which has all those cool Celtic pull-offs, as well as “My Old Flame” and a super-funky “Junco Partner,” which showcases your great syncopated chording.

"Well, I got a loop going on 'Danny Boy,' just a low, deep drone kind of thing from tuning the low E down to D. 'My Old Flame' is a tune I used to play with Charlie Haden when we did some duet gigs together. And I love the Professor Longhair version of 'Junco Partner.' I got to play that song with Dr. John. Such a great New Orleans song."

The Hank Williams tune "You Win Again” really brings out your vocal string-bending quality.

"The string bending came from starting out with blues and rock. I guess a lot of jazz guys don’t do it as much as I do. I use an unwound third string, a .022. I guess most use a wound third string. You can get an expressive thing bending the notes and sliding into them. It’s just not part of the standard orthodox jazz guitar vocabulary, I guess. But for me, vibrato and bending… you gotta do it for soul. I think I got more into it last decade or so. But yeah, you gotta bend the notes. That’s part of our American tradition!"

Hearing standards like “It Could Happen to You” and “There Will Never Be Another You” reminds me of that great record you did in the ’80s with John Abercrombie, Solar.

"Okay, yeah, as if there were two people, one comping for the other. And it’s swinging!"

You also do the Keith Jarrett tune “Coral.” I didn’t remember that you had previously recorded that on that Jarrett tribute album from 20 years ago [2000’s As Long As You’re Living Yours: The Music of Keith Jarrett].

"Yeah, somebody reminded me of that recently. I had forgotten that I recorded that. And that was with Dennis Irwin on bass and the late great Ralph Peterson on drums. I’ve known that tune forever."

Listening to “Honest I Do” made me go back and re-appreciate that album with Frisell from 1992.

"Yeah, that was from Grace Under Pressure. That was a great album."

You’ve done so many albums, but you’ve come up with something new and different on this one.

"Yeah, I’ve done so many records. Maybe too many. But if they keep letting you, you just do them, you know? And this one is really different."

You also cover “Not Fade Away.” I know that you’ve done some touring and playing with Phil Lesh. I’m curious to know if you ever played “Not Fade Away” with him, because that was a Grateful Dead anthem.

"Yes, I think Phil Lesh plays that song on every gig. Of course, my version of 'Not Fade Away' is not from the Dead but from Buddy Holly."

I think I first heard that tune by the Rolling Stones on their debut album in 1964.

"Oh, that’s right! That’s probably where I heard it first, actually. I have this vision of Mick Jagger playing maracas on that song, maybe on The Hollywood Palace or The Mike Douglas Show or Shindig! or some other TV show. So it was a song we all grew up with. And really, it’s got that Bo Diddley beat. It’s only rock and roll, and I like it!"

This solo album is a real achievement. I wouldn’t have thought that you’d get so hip to technology at this point in your career.

"Man, I just stepped on some pedals and let it all happen. I have no idea how it works."

Did you have a previous incarnation of that Boomerang pedal with the band that made Up All Night [recorded in December 2002 and January 2003]?

"Not even a previous incarnation. It’s that same pedal. I used it for weird reverse solos and things with that band. That’s how I got into it, having a bunch of sonic things happening with that band. If my Boomerang pedal broke now – and they don’t make it anymore – I don’t know what I would do. Because my routine doesn’t work on the other ones, not that I know of."

I remember seeing you play a blues gig with Robben Ford’s trio for a week-long engagement at the Blue Note in 2009. I’m surprised you never recorded that.

"Right, we never did. I was playing a pink Strat on that gig. I was teased so much about it, but it sounded good. Actually, there is a bootleg recording of that that’s supposed to be pretty good that the drummer Toss Panos recorded at his house. He has like a full recording studio. We rehearsed there and learned all those tunes there. So I guess it’ll come out at some point.

"You know, there are so many things that I’m currently doing that I never got back to that project. And Robben ended up moving to France. [Ford announced the move earlier this year on social media.] So I don’t know if that will happen again."

Meanwhile, you’ve been doing some duet tours with Dave Holland.

"Yeah, in November of last year when things first opened up again, before Omicron, we played the Blue Note and did a tour of Europe. That’s another project that I would like to record sometime.

"Dave is incredible, man. I mean, he’s a monster musician. And beyond the technique of the bass, which he is a master at, he’s just really, really good to play with and be around. And I’m also doing some touring with my new rock band, Yankee Go Home, which is Jon Cowherd on keyboards, Vicente Archer on bass, and Josh Dion on drums. We’ve been having a blast on the road with that band. We’re going to be doing a recording next year, so stay tuned for that one."

Bill Milkowski's first piece for Guitar Player was a profile on fellow Milwaukee native Daryl Stuermer, which appeared in the September 1976 issue. Over the decades he contributed numerous pieces to GP while also freelancing for various other music magazines. Bill is the author of biographies on Jaco Pastorius, Pat Martino, Keith Richards and Michael Brecker. He received the Jazz Journalist Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 and was a 2015 recipient of the Montreal Jazz Festival's Bruce Lundvall Award presented to a non-musician who has made an impact on the world of jazz or contributed to its development through their work in the performing arts, the recording industry or the media.