John Petrucci: "There Are Moments that You Can Pinpoint and Say They Were Truly Life-Changing, and for Me, Hearing Steve Morse Play Guitar Was One of Them”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“How does anybody play guitar like that?” Dream Theater guitarist and main man John Petrucci says, recalling his reaction when he first heard the music of Steve Morse. “It was the wildest, most incredible stuff I had ever heard. There are moments that you can pinpoint and say they were truly life-changing, and for me, hearing Steve Morse play guitar was one of them.”

It was the mid ’80s and Petrucci was a metal-crazed high schooler and budding guitarist big on Metallica, Iron Maiden, and Ozzy Osbourne. “I spent most of my free time practicing, and I thought I was getting pretty good,” he says. “I could play a lot of the stuff by my heroes pretty well.”

One day, a friend’s older brother gave Petrucci a mixtape of tracks by the Dixie Dregs, a band the young guitar player had vaguely heard of, along with a sage piece of advice: “You have to listen to Steve Morse.”

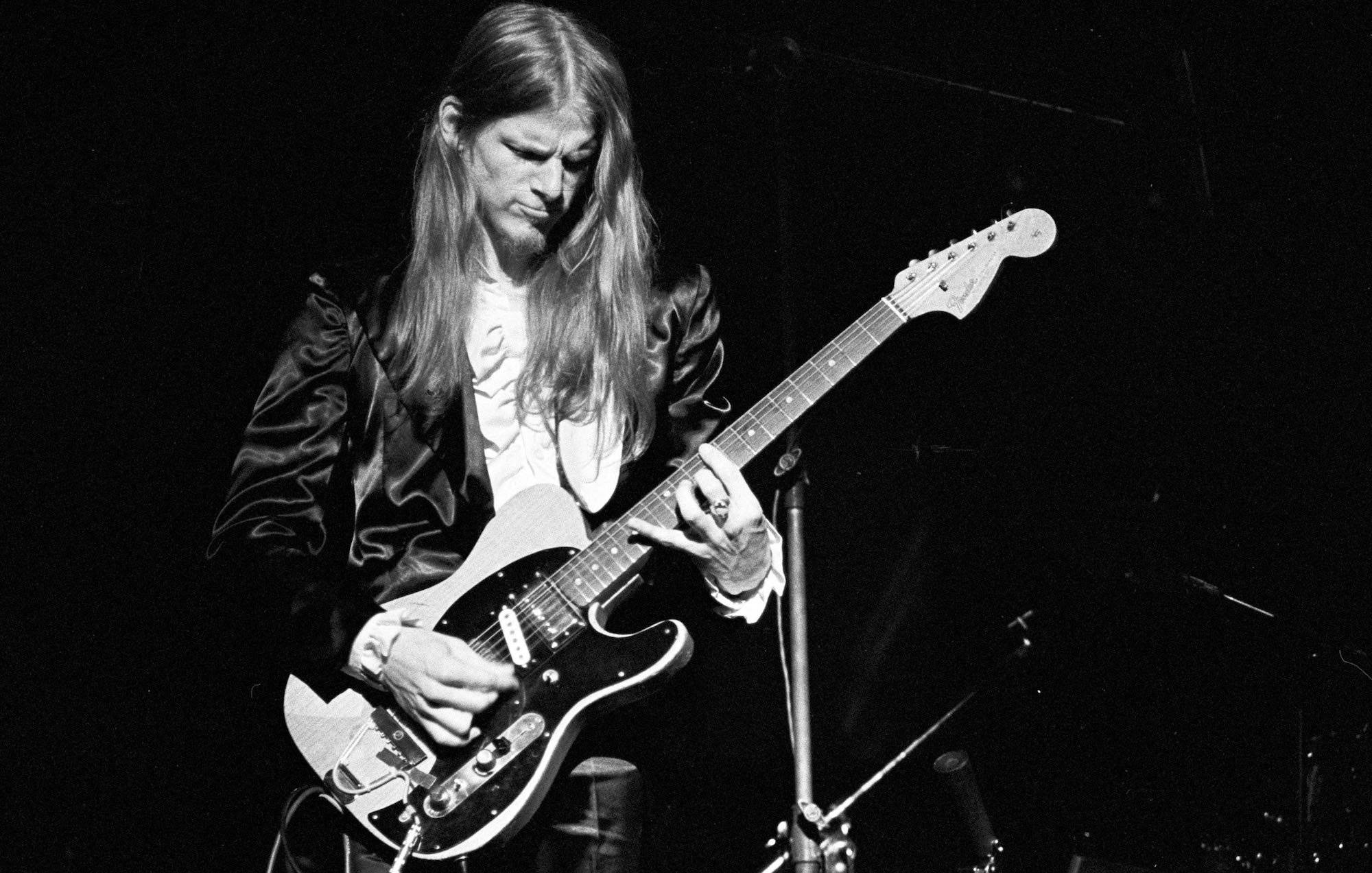

Petrucci didn’t know what to expect when he loaded the tape in his deck. The first song that came up was “The Bash,” an exuberant, revved-up and rocking country jam on which Morse charges out of the gate like a bucking bronco, blitzing across the fretboard and spinning wild chicken-picking licks all over the neck while keeping pace with Allen Sloan’s hyper-giddy violin lines.

“It totally blew my mind,” Petrucci says. “I couldn’t understand how anybody could play like that. I wasn’t very familiar with bluegrass, but Steve mixed it with rock in such an exciting way. His technique and phrasing hooked me immediately.”

From that moment, Morse zoomed to the top of the list as Petrucci’s favorite guitar player. “I even transcribed the song, because I wanted to learn how to play like that,” he says. “I did the deep dive and immersed myself in all things Dregs and Steve Morse. Whatever he played, I had to hear it. He became ‘the guy.’”

By Petrucci’s estimation, Morse’s impact on his guitar playing has been incalculable. “He helped bend and shape my approach to the guitar in so many ways,” he says. “The first was compositionally. I loved how he could incorporate rock, bluegrass, and classical, and that added flavors to my repertoire. Technically, Steve took me to a very high level. I read about his approach to practicing, and that prompted me to apply his work ethic to my own practice routine. I said, ‘I’m going to do what he did and follow in his footsteps.’”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Happily, Petrucci reports that the oft-repeated adage “don’t meet your heroes, they’ll only disappoint you” doesn’t apply to here. After first encountering his idol at a guitar clinic Morse was conducting, Petrucci, by then a guitar star in his own right, went on to establish a peer-to-peer relationship with him.

“Developing a real friendship with Steve has been remarkable,” he says. “Over the years, we’ve played together and have done some writing together. We’ve toured together, Dream Theater and the Dregs. We share the same manager, and we both have a relationship with Ernie Ball Music Man, so we’ve done a lot of events together. It’s just incredible. I love hanging out and doing signings with Steve. He’s always so smart, insightful, and funny. I’m still like a kid who’s in awe of him, and I always will be.”

For his part, Morse seems similarly bedazzled by Petrucci. “I would hear him on records, and his playing was so astonishing,” he says. “I’d think, This guy just can’t be real. It’s rare to find somebody who really pushes the limits of everything that can be done on the guitar, and John does that so powerfully. I find that very inspiring.”

He recalls going backstage to meet with Petrucci before a Dream Theater show. “It was the first time I really hung out with him,” Morse says. “John was warming up, and it confirmed to me, Yep, he’s human. I thought, He’s going to start at this tempo, he’s going to increase it, and he’s going to put in the time so that when he hits the stage, he’s gonna explode.

"He let me witness what is usually a very private time, and that really struck me as being meaningful. It was like him telling me, ‘I’m comfortable enough with you to let you see what I do when I’m alone, because I know you’ll understand. And then I’m going to go out and kill people.’ Which he did. It was a big deal.”

Hearing this for the first time, Petrucci lets out a laugh. “And the whole time, I was freaking out inside. All I was thinking was, Oh, my god. Steve Morse is watching me warm up!”

Guitar Player recently extended an invitation to Petrucci to lead Morse in a mentor-mentee discussion about his career and shredcraft. Within minutes of the two men sitting down to chat, it became clear that this wouldn’t be a standard Q&A session but rather an engaging, relaxed, and at times freewheeling exchange between two giants of the guitar… who also happen to be very good friends. We present their conversation, with Guitar Player occasionally chiming in.

Influences

John Petrucci: "Steve, I’m reminded about something. I did an interview one time and I mentioned how you were my biggest influence, and then something happened that I’ll never forget: You called me."

Steve Morse: "Oh, yeah. I remember that!"

Petrucci: "It was the coolest thing. I guess you got my number from our mutual manager, Frank Solomon. You left a message on my answering machine. It meant so much to me. In fact, we still have the answering machine with the tape and your message. I cherished it so much. It was so awesome that you did that. You didn’t even know me at the time."

Morse: "Yeah, well, I was very impressed with your band. But you as a guitar player, it was so incredible to me to hear somebody at such a young age who had this command of the instrument. It wasn’t like you had this one trick, you know? And the thing about you is, you keep getting better."

Petrucci: "Oh, my…"

Morse: "Well, it’s true. You think, This guy can’t possibly get any better, but then you do. I was listening to your last solo album [2020’s Terminal Velocity], and your playing is just effortless. There’s great writing and ideas, and everything musically is performed with such control. Your vibrato – it’s all right there. It’s like, I can’t handle it. [laughs] And you do it on each recording. I don’t know how you do it, but you do."

Petrucci: "Oh, wow… That’s such praise. Of course, my whole practice mentality came from reading articles about you – interviews in which you talked about your discipline and your own practice routine. That’s what got me into using a metronome and really putting the hours in. What inspired me about you was how you talked about setting a goal and going about achieving it, no matter how long it took.

"The only other person I read about who did something similar was Randy Rhoads, and how he started learning classical guitar. I’m curious: Who had that kind of impact on you?"

Morse: "Well, it’s kind of a long story. For me, that all started with John McLaughlin. I went to see him and the Mahavishnu Orchestra at this outdoor show at our college, only the gig was rained out and they had to set up in the cafeteria. I got to be the first person right in front of the whole band."

Petrucci: "Wow!"

Morse: "I was sitting on the floor and they were up on a small stage. The power and energy from the band was incredible. I was close enough to see that John McLaughlin was picking every note, and he sounded incredible. He just destroyed everybody. It was that moment where everything was like, 'Yes!' It made me think playing guitar at this high level could be very effective. It was never going to be pop music or a path to riches, but it was something that interested me deeply.

"In music school, I was studying piano. Everybody had to. I remember hearing my teacher talking with one of her students who was worried about an upcoming recital and said, 'I don’t know. I’ve just made some mistakes.' And the teacher said, 'Well, let’s go through it. Have you been practicing your four to six hours a day? Have you been doing your memory practice so you can work on the piece without being in front of the instrument? Have you done the analysis? Have you done this? Have you done that?' It was a complete checklist.

"That was the level that you had to be at if you were going to play at a recital, and I just remember thinking, Wow! So that really impressed me, and it helped push me in terms of what I expected out of practice. I expected myself to be able to do what a keyboard player could do."

Petrucci: "Hearing you talk about seeing McLaughlin and how he picked every note reminds me of how I felt when I heard you play “The Bash” [from the Dixie Dregs’ 1979 album, Night of the Living Dregs]. All the guys I was into before that were really good technically, but they didn’t play like that. From that point on, my whole mentality was like, I need to be able to pick every note.

"Then I got into Al Di Meola and other players who could pick every note. It became something of a litmus test, like, only real players can do that. You know, none of this wimpy hammer-on sweeping. [laughs] Now, as I’ve learned about guitar since, all the techniques are awesome, and it’s fun to be able to do everything. I’m not as snobby as I was as a teenager. But there was a period where I was like, 'I’ve got to pick every note because that’s what Steve Morse does.'"

Morse: "Picking every note was a way to be more versatile. Wrist licks and those 'tweedly-tweedly' pull-offs are extremely natural, and they work great for blues and rock stuff, but what about classical music and stuff where you’re playing along with a horn player, a keyboard player, or a violinist?

"I’m talking about stuff where the music doesn’t necessarily lay out that well on the guitar."

Petrucci: "Exactly."

Morse: "Fingering-wise, nobody knows more about that stuff than you, John. You play with [Dream Theater keyboardist] Jordan Rudess."

Beating The Keyboard Player To The Punch

Petrucci: "Well, that leads me to a question for you, Steve. As you know, I’ve been playing with keyboard players for years, so I’ve always been in a position where they’ll come up with something that feels incredibly comfortable to them, and then it’s like, 'Okay, play this on guitar.' And I’m like, 'Why are there so many fourths?' Translating it to guitar isn’t always so easy. My approach is to figure out the easiest way to play it. What do you do?"

Morse: "Well, the first thing I try to do is beat the keyboard player to the punch."

Petrucci: "Of course! [laughs]

Morse: "When writing something with a keyboard player, I’ll say, 'What was the best voicing for that other chord?' Then while they’re trying to figure out what I’m talking about, I’ll start thinking, Oh, this line will work, and that line will work… 'Oh, by the way,' I’ll say, 'I’ve got an idea for that fast part.'

Petrucci: "That’s awesome. I love it."

Morse: "That way, I know I can play whatever it is, because I’ve already worked out all the possibilities. I do that every single time. Well, I mean, I try to do it. Sometimes you can get stuck.

"Once when I was working with Flying Colors [Morse’s prog-rock side project], [singer] Neal Morse came up with something. He showed it to me, and the tempo was okay. Then [drummer] Mike Portnoy came in, and pretty soon the tempo got faster and faster, to the point where it was just screaming. It was almost impossible. I had to keep changing the fingering to keep up. It was just one of those things: You do what you have to do."

Petrucci: "I hear you."

Morse: "You had mentioned fourths. When I was at the peak of my technique, I could play fourths across the strings at about 80 percent of the speed that I could play fast single notes – linear notes, rather. Guitar players tend to think more linear, and when you come up with lines and present them to a keyboard player, it’s funny watching them learn it, because it’s not natural for them.

"They have to use two hands. It’s very easy for us to repeat a note and do a tremolo thing, but it’s really hard for them."

Working Harder

John, you had mentioned hearing Steve play “The Bash” the first time on record. What did you think the first time you saw him play it live? Was it with the Dregs?

Petrucci: "No, it was with the Steve Morse Band. When he played clubs like My Father’s Place [a former music venue in Roslyn, New York] with the Dregs, I was too young to get into bars. I kind of missed that whole period.

"I first saw Steve when he put out The Introduction [the Steve Morse Band’s 1984 debut album] and he was playing with a trio on Long Island. Seeing him live was amazing. I was blown away by several things. [to Morse] You guys were a trio but you sounded huge – so full and musical. I loved your guitar sound. And, of course, you had multiple volume pedals, and you were bringing delays in, and chorus. It sounded so beautiful.

"You were playing lines that I had only heard on tapes and records, but now you’re playing them before my eyes. You were sort of combining parts. I was amazed that all this sound was coming out of one guitar player. I would go to see you again and again, and I remember having this feeling that you kept getting better every time."

Morse: "That’s very kind. I was trying to get better."

Petrucci: "Actually, I met you before that. I was a student at the Berklee College of Music, and I went to see you at a clinic at a music shop right by the school. I remember waiting in line, and you walked in with your gig bag. I was freaking out, like, 'Oh, my God. There he is! That’s him!' [laughs] At the clinic, you taught all this stuff, and I don’t know if I had written it out while you were talking, but I immediately went back and learned it all.

"I still practice the things that you taught at that clinic. I was 18 years old. You taught me something very valuable that day about how you hold your pick, the way you sort of make this pocket so you can mute certain strings while letting other strings ring. That’s something I’ve used forever."

Morse: "You mentioned that period when I did the trio stuff. Doing that, I could use a lot of my classical left hand to try to make the voicings bigger. You have to work a little harder in a trio format. And, of course, I could use [bassist] Dave LaRue’s talent."

Petrucci: "Whenever I would see you in those trio situations, you did look like you were working really hard. You had all these pedals, and you were working your guitar through various pickups. It seemed like such an intense level of concentration, beyond all the nerdy playing aspects. How did you prepare for that?"

Morse: "I would think it was similar to what you would do with a trio. I would get Dave to come over, and we’d work without a drummer – we’d work to a click. But sometimes [drummer] Van [Romaine] would come over and we’d rehearse for a day.

"A lot of the stuff I do involves switching from a distorted sound to a clean sound; I’m going from my guitar volume on 10 to somewhere between three or four. It’s variable. Every time I do it, it’s going to be slightly different. And then I work with the short delay or long delay, maybe some chorus. Plus, I’m changing the pickups at the same time, trying to make up for the high end that’s lost by turning down the guitar that’s plugged into a distorted amp. Trying to manage it all is a bit difficult, but you figure out a way to connect everything."

You do realize, John, that you’re talking to a guy who can fly a plane and practice guitar at the same time?

Petrucci: "I know. Who can do that?"

Morse: "Anybody could do that."

Petrucci: "Oh, sure! [laughs]"

Morse: "No, seriously. To be a good pilot is all about judgment. Writing is the same way. Art is all about judgment – the balance and looking ahead. The same is true for flying. It’s all about realizing how many things you need to be on top of. You control what you can, and if you think you can’t stay in control of something, you take an alternate route, so to speak."

Petrucci: "I would read about you, Steve, how you could drive and practice at the same time. It made me feel like the ultimate slacker."

Morse: "Sometimes on long trips there just wasn’t any time to practice. What I would do was, I’d put this fleece pad – like one of those shoulder-belt pads – on the steering wheel, and I would drive with my knees while playing the guitar. If the road was crowded, I wouldn’t do that, but if I was on an interstate and no cars were around, sure, I could manage it. It’s only a few inches from the guitar neck to the steering wheel, so you can get your hands back on the wheel pretty quickly."

Finding Your Voice

Both of you have established your own musical identities and found success by bucking musical formulas and industry expectations. How hard was it to stick to your guns and not play it safe?

Petrucci: "It can be hard and scary sometimes. For me, it’s all Steve’s fault. [Morse laughs] No, it’s true, in a way, because I was a young musician getting into rock music and playing guitar. And then I heard the Dregs and I thought, There’s more to this than what other people are doing. And I include Yes and Rush in that – they followed their own paths.

"I decided that I wanted to play music that is more challenging and more nontraditional as far as structure, and that kind of attitude really bucks the whole system. But that’s what I wanted to do. It’s been an uphill battle at times, sure, but we’ve been fortunate to make a career out of doing a style of music that we love.

"We’re really proud to be part of this big prog family tree that includes Steve and the Dregs. For as scary and difficult as it is, it’s also really rewarding. You’re doing things on your own terms, and you’re forging your own path.

"I was into the Dregs, Rush, Yes, Iron Maiden, and Metallica, so when I played, it sounded like a metal version of instrumental prog music. But I never heard any music like yours before, Steve. I never heard anything that sounded like the Dregs. It was so original. How did you come up with that? I’m really curious."

Morse: "That’s a good question, and there’s a lot in that. See, by the time you heard my music, I had played in bluegrass bands and rock bands. I’d played in many cover bands and studied classic guitar. I’d written pieces for classical guitar, and I was in a weird band that we called Dixie Grit. The name was just a joke, because none of us were really from the South. It was just a funny joke. We’d get hired for dances and the people would flip out – not in a good way. [laughs] People just hated it.

"That band eventually broke up, and then it was just [bassist] Andy West and me. We got another drummer and started something else. It was all like, 'What can we do?' We threw ideas around and put together a three- piece band. We played a free concert for college kids, and it went over well enough to inspire us. I noticed people could put up with a lot of variety – and not just put up with it but really enjoy it. That’s something the music business doesn’t encourage.

"The business is all about niches – radio stations play only one type of music, and they only play the hits. Record stores back then were the same way. The whole thing made me feel alienated from the business of music, so I concentrated on what was in front of me, which was the music itself. We played a lot of free gigs early on. Because I wrote the music and didn’t have to look too much at my fingers, my eyes were always on the audience.

"I watched them and noticed what would make them get up and walk away. What would make them stop and listen? That’s when I realized it was melody and changes, getting in and out of sections and back to the melody. When we did solos, they couldn’t be too long. I put a four-minute cap on the songs, and I kept writing things and imagining people listening and smiling, or maybe they’d be moving their heads and tapping their feet.

"This was in Miami, which was quite a cosmopolitan place at the time. That experience really helped me feel like there was a future for what I wanted to do. I knew that it was never going to be big commercially, because I could see the popularity of the stereotypical things. But once I saw people liked the variety of music that we played, and they could see we were having a good time doing it, it gave me the push to continue."

Leading The Band

You two have something in common in that you’re both band leaders. Did that come naturally to you?

Petrucci: "In my case, it did. There are some guitarists – amazing virtuoso players – who join somebody else’s band, and they’re quite happy in that role. However, I think there’s a certain kind of personality that makes somebody gravitate toward the position of leading a band.

"Without sounding like a megalomaniac, I like to have my hand in things. I like to do the work. I have a very specific way that I think about things and how I imagine things should be presented musically and visually, and how business should be run. I’ve been producing the band for a while now, and I feel as if that’s my comfort zone. I like being able to see things through, not only to my own satisfaction but also in a way the band can feel happy about.

"It’s not about being a dictator in these situations. If you’re a good leader, then you want to respect and use everybody’s talents; you want to bring out the best in everybody. Some people don’t feel comfortable in that role. Others have it thrust upon them: 'Okay, nobody wants to lead the band, so I will.' I welcome it."

Morse: "I can say that John is a natural leader, so that makes him an excellent band leader. He has a vision and he knows how to persevere. He has a patience level that I know I don’t have. I kind of envy him for that. [laughs] When he wants to do something right, he puts his mind to it."

Petrucci: "Yeah, but I got so much of that from you!"

Morse: "Well, thank you, but I think you had it in you all along. Now, see, with me and the Dregs, I sort of fell into my niche and it evolved into the musical dictator. It started with Andy West and me: 'What do you want to do? How about this? Oh, how about you play that?' After a while, it came back to me to decide. I was kind of like the kid in class who always had his hand up: 'Pick me, pick me! I know!'

"Whenever it came to a musical question, the rest of the people in the band kind of sat there because I would still be talking: 'Let’s do this. Let’s change that. And, oh, can we change that other thing?' It’s just the way I am. I like to run through the possibilities. I was happy to defer to the guys on other matters. But as far as having the big picture about the music, yeah, that kind of fell on my shoulders. I never minded."

Behind The Guitars

You two also share a connection to Ernie Ball Music Man: You’ve both designed signature guitars with the company.

Petrucci: "Steve, you were first with that."

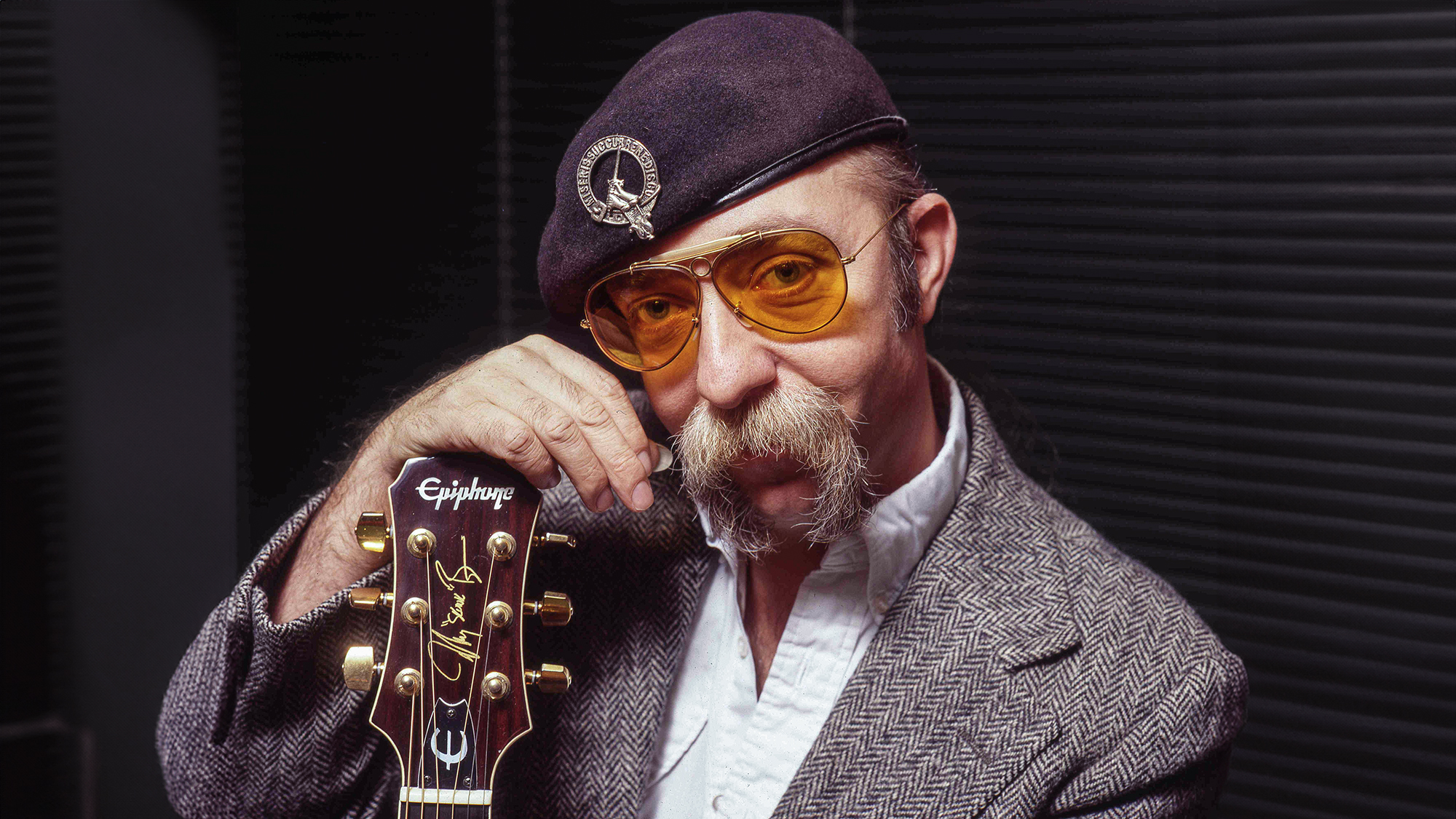

Morse: "Yeah, what happened was, Sterling Ball asked me about doing a guitar. I had an experience with another company that kind of soured me. Whenever I would present an idea, they would say, 'You can’t do that,' so that was a real turn-off. But Sterling said, 'There’s only one rule: We won’t stop until you’re happy.' I said, 'I can live with that.' So we went to it.

"We did some prototypes, and very soon after I was playing them all the time. I put my Tele Strat down. [Morse’s main guitar with the Dregs was a Frankenstein made from a Telecaster body, a Stratocaster neck and a complex array of electronics.] The guitar I designed with Ernie Ball Music Man turned out to be all the guitar I ever needed. I’ve still got serial number one. When John came along, things went to warp speed with what they could do in terms of design."

Petrucci: "For me, the relationship with Ernie Ball Music Man came about in a serendipitous way. I had been using another brand, but my manager, Frank Solomon, called me up and told me what they were doing with Sterling Ball. I was playing another guitar, but I did use Ernie Ball volume pedals, and I loved those.

"A friend of mine who was teching for me at the time said, 'Man, you’ve got to play a real guitar. You’ve got to play Music Mans.' Frank set up a call with me and Sterling, and we hit it off. Of course, having my favorite guitar player of all time as an Ernie Ball Music Man endorser sealed the deal. I thought, 'If it works for Steve Morse, it’ll work for me.' Sterling said the same thing to me: 'We’re not going to stop until it’s right. We make tools for artists.'

"I just celebrated 20 years with Ernie Ball Music Man. It’s been such a great experience. Beyond building guitars, there’s a family there. I’m proud to play these guitars and be a part of the family.

"Working with them, I really got into design. It opened me up to so many ideas: 'Why can’t this be over here? Why does this have to be so hard to reach?' The idea that a guitar can still be improved and it can be exactly what you want has been a real revelation to me."

Morse: "That’s the way John’s mind works: 'Why can’t this be better? How can we make this thing better?' For most people, good enough is the end of everything. For John, it’s a starting point. The way he designs these amazing guitars from start to finish takes an incredible level of commitment and discipline."

Petrucci: "You’re the same way. You’ve always been an inspiration in that you’re a problem solver."

Morse: "I just don’t know any other way to go about things. It drives some people crazy, but I always try to bring them around to my side."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.